Between Being and Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Chris Riddell Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2016 UK Illustrator Nomination PHOTO : JO RIDDELL PHOTO

Chris Riddell Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2016 UK Illustrator Nomination PHOTO : JO RIDDELL PHOTO 1 Chris Riddell Biography Chris Riddell A Critical Appreciation Chris Riddell was born in South Africa. His father Richard Platt. This book and the earlier Castle Diary Chris Riddell is highly regarded in the UK and well as young readers’ chapter books, he addresses was an Anglican clergyman and his parents were involved him in detailed historical research, which internationally as a visual commentator and an audience that is often neglected: readers active in the anti-apartheid movement. His family he deployed in typically boisterous, characterful narrator; an artist and illustrator in command of who are still young enough to enjoy illustrations returned to Britain when Chris was a year old and and humorous style. Perhaps his most demanding a range of forms and genres varying from political supporting a narrative, but also old enough to he spent his childhood moving from parish to illustration project to date followed in 2004 with satire and cartoon to picture books, graphic novels engage with more sophisticated subject matter. parish. His interest in drawing began then and was his illustrations to Martin Jenkins’ adaptation of and cross-over forms. His broad understanding of Chris Riddell’s biggest virtue, however, is not that encouraged at secondary school. He remembers, Gulliver’s Travels, a classic whose combination visual communication, coupled with his classical he satisfies the expectations of theoretical analysis, “I had a wonderfully idiosyncratic art teacher, Jack of satire and fantasy played to his strengths as drawing ability and extended frame of reference, but that he can do so whilst communicating with Johnson, a painter who’d also been a newspaper an illustrator and earned him the second Kate has earned him the respect of broad and diverse and convincingly addressing his audience. -

The Graveyard Book Booklet 202021

King Charles I School Name: Tutor Group: 1 Reading Schedule You must read for at least 30 minutes per day The questions and tasks are optional and are there to extend your understanding of the novel. Week Pages to read 1 1-89 7th September Chapter 1-3 2 90-154 14th September Chapter 4-5 3 155-198 21st September Interlude-Chapter 6 4 199-289 28th September Chapter 7 - 8 2 Context: Author: Neil Gaiman Neil Gaiman was born in Hampshire, UK, and now lives in the United States near Minneapolis. As a child he discovered his love of books, reading, and stories, devouring the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, James Branch Cabell, Edgar Allan Poe, Michael Moorcock, Ursula K. LeGuin, Gene Wolfe, and G.K. Chesterton. A self-described "feral child who was 5 raised in libraries," Gaiman credits librarians with fostering a life-long love of reading: "I wouldn't be who I am without libraries. I was the sort of kid who devoured books, and my happiest times as a boy were when I persuaded my parents to drop me off in the local library on their way to work, and I spent the day there. I discovered that librarians actually want to help you: they taught me about interlibrary loans.” 10 Gaiman's books are genre works that refuse to remain true to their genres. Gothic horror was out of fashion in the early 1990s when Gaiman started work on Coraline (2002). Originally considered too frightening for children, Coraline went on to win the British Science Fiction Award, the Hugo, the Nebula, the Bram Stoker, and the American Elizabeth Burr/Worzalla award. -

Table of Contents Answer Key Introduction

Table of Contents Answer Key Introduction . 3 Sample Lesson Plan . 4 Page 25 9. Accept appropriate responses. Before the Book (Pre-Reading Activities) . 5 1. Accept appropriate responses. 10. Accept appropriate responses. About the Author and the Illustrator . 6 2. Answers will vary, but should include the Pages 35 and 38–41 Book Summary . 7 following features: enormous body, covered Vocabulary Lists . 8 in tattoos, rippling forearms, a broad neck, a Most answers will vary due to the students’ opinions. Vocabulary Activity Ideas . 9 bald head, a broad nose, bloodshot eyes, wears a patterned dress. She is ferocious Section 1 (Chapters 1–3) . 10 and mean (or similar). Page 42 • Quiz . 10 3. He is wearing a banderbear skin. 1. • halitoad – a creature with foul breath • Charms and Amulets – hands-on research project . 11 4. She is an apothecaress (or apothecary), • torrent – a violent stream of something • Noises in the Deepwoods – using cooperative learning to create a ‘soundscape’ . 12 which is similar to a chemist. She uses a • acrid – sharp or irritating smell or taste • A New Sport – connection to design and technology/society and environment . 13 variety of herbs, flowers and animals to • faltering – using unsteady movement • Reading Response Journals – connection to students’ lives . 14 make potions and poultices. She tells Twig • amulet – a charm Section 2 (Chapters 4–7) . 15 she understands the properties of most of • treacherous – unreliable • Quiz . 15 the things that live and grow in the forest. • plaintive – sorrowful • A Postcard from Twig – hands-on writing project . 16 5. He follows Mag and falls into an • chasm – a deep gap in the earth’s surface • Goblin Interview – using cooperative learning to conduct character interviews . -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Interview with Chris Riddell, Autumn 2004

CHRIS RIDDELL CHARTS Art history: Riddell’s studio contains displays of dustjackets and tiny paper Lilliputians he OF THE made to ensure that drawings for Gulliver’s Travels SKY PIRATES were to scale. Fantasy doesn’t sell. Teenagers won’t buy books with pictures. This is what illustrator Chris Riddell and writer Paul Stewart were told in the 1990s. A million copies of the Edge chronicles later, they tell Ruth Prickett that their success rests on attention to detail – from architecture and economics to fashion and cartography In the beginning was a map. There aren’t many authors who would admit that their hugely successful series started with an illustration. But then there aren’t many partnerships that work like that of Chris Riddell and Paul Stewart, co-crea- tors of the phenomenally popular fantasy series the Edge chronicles. The story goes that in the mid-1990s Chris Rid- The dell, already a well-known children’s illustrator and newspaper cartoonist, came up with a map of the sur- real Edge world. He and Paul Stewart used this as the basis for their first collaboration, Beyond the Deep- woods. They showed it first to his publisher who was entertained, but dismissed it, telling them: “There’s no future in fantasy”. Stewart’s publisher, however, was more confident, and the Edge legends were born in 1998, the same year the second Harry Potter book was published, but before Harry Potter mania had every publisher reaching for his chequebook. Riddell provided the hundreds of intricate line edgedrawings that appear throughout the text, but his 14 ILLUSTRATION AUTUMN 2004 CHRIS RIDDELL input was not restricted to illustrating Stewart’s pre- conceived story. -

February 2021

F e b r u a r y 2 0 2 1 V o l u m e 1 2 I s s u e 2 BETWEEN THE PAGES Huntsville Public Library Monthly Newsletter Learn a New Language with the Pronunciator App! BY JOSH SABO, IT SERVICES COORDINATOR According to Business Insider, 80% of people fail to keep their New Year’s resolutions by the second week in February. If you are one of the lucky few who make it further, congratulations! However, if you are like most of us who have already lost the battle of self-improvement, do not fret! Learning a new language is an excellent way to fulfill your resolution. The Huntsville Public Library offers free access to a language learning tool called Pronunciator! The app offers courses for over 163 different languages and users can personalize it to fit their needs. There are several different daily lessons, a main course, and learning guides. It's very user-friendly and can be accessed at the library or from home on any device with an internet connection. Here's how: 1) Go to www.myhuntsvillelibrary.com and scroll down to near the bottom of the homepage. Click the Pronunciator link below the Pronunciator icon. 2) Next, you can either register for an account to track your progress or simply click ‘instant access’ to use Pronunciator without saving or tracking your progress. 3) If you want to register an account, enter a valid email address to use as your username. 1219 13th Street Then choose a password. Huntsville, TX 77340 @huntsvillelib (936) 291-5472 4) Now you can access Pronunciator! Monday-Friday Huntsville_Public_Library 10 a.m. -

The Drink Tank 252 the Hugo Award for Best Novel

The Drink Tank 252 The Hugo Award for Best Novel [email protected] Rob Shields (http://robshields.deviantart.com/ This is an issue that James thought of us doing Contents and I have to say that I thought it was a great idea large- Page 2 - Best Novel Winners: The Good, The ly because I had such a good time with the Clarkes is- Bad & The Ugly by Chris Garcia sue. The Hugo for Best Novel is what I’ve always called Page 5 - A Quick Look Back by James Bacon The Main Event. It’s the one that people care about, Page 8 - The Forgotten: 2010 by Chris Garcia though I always tend to look at Best Fanzine as the one Page - 10 Lists and Lists for 2009 by James Bacon I always hold closest to my heart. The Best Novel nomi- Page 13 - Joe Major Ranks the Shortlist nees tend to be where the biggest arguments happen, Page 14 - The 2010 Best Novel Shortlist by James Bacon possibly because Novels are the ones that require the biggest donation of your time to experience. There’s This Year’s Nominees Considered nothing worse than spending hours and hours reading a novel and then have it turn out to be pure crap. The Wake by Robert J. Sawyer flip-side is pretty awesome, when by just giving a bit of Page 16 - Blogging the Hugos: Wake by Paul Kincaid your time, you get an amazing story that moves you Page 17 - reviewed by Russ Allbery and brings you such amazing enjoyment. -

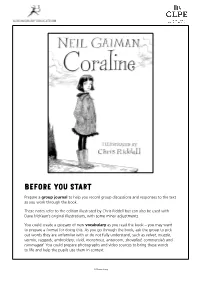

BEFORE YOU START Prepare a Group Journal to Help You Record Group Discussions and Responses to the Text As You Work Through the Book

BEFORE YOU START Prepare a group journal to help you record group discussions and responses to the text as you work through the book. These notes refer to the edition illustrated by Chris Riddell but can also be used with Dave McKean’s original illustrations, with some minor adjustments. You could create a glossary of new vocabulary as you read the book – you may want to prepare a format for doing this. As you go through the book, ask the group to pick out words they are unfamiliar with or do not fully understand, such as velvet, muzzle, vermin, raggedy, embroidery, vivid, monstrous, anteroom, shovelled, commercials and rummaged. You could prepare photographs and video sources to bring these words to life and help the pupils use them in context. © Bloomsbury SESSION 1: CHAPTER 1 Focus: Predicting, Close Reading, Thinking Aloud and Summarising Share the front cover with the group. (Do not share the back cover at this point as it reveals some aspects of the plot you may wish to hold back while the children make predictions.) Ask the children to predict what the story could be about. Ask them to justify their responses, drawing out any connections they make to other stories. Record the children’s responses in the journal. Once you have recorded their predictions you can return to these as you read the book, comparing the children’s initial thoughts to how the story actually unfolds. –––––– © Bloomsbury Encourage the children to look in detail at the cover illustration and make connections between this text and other stories they know. -

CHRIS RIDDELL Has Written Highly Acclaimed Books for Both Ship’S Cook

QC Preflight Point QC Preflight Point 3rd 0 0 NEIL GAIMAN NEIL NEIL GAIMAN Pirate Stew! Pirate Stew! ILLUSTRATED BY NEIL GAIMAN Meet Long John McRon Pirate Stew for me and you! CHRIS RIDDELL has written highly acclaimed books for both Ship’s Cook . children and adults and is the first author to Pirate Stew! Pirate Stew! A most unlikely babysitter . have won both the Carnegie and Newbery Eat it and you won’t be blue. Medals for the same work – The Graveyard Book. You can be a pirate too! Long John McRon and his wild crew are Many of his books, including Coraline and about to transform a perfectly ordinary Stardust, have been made into films; A joyful, funny feast of a story, with all evening into a riotous adventure Neverwhere has been adapted for TV and radio, the ingredients of a book you’ll read beneath a pirate moon – with the help and American Gods and Good Omens have been and love forever. adapted into major TV series. He has also of a very unusual recipe. From Carnegie and Newbery Medal-winner written two episodes of Doctor Who and QC Preflight Point Neil Gaiman and Greenaway appeared in The Simpsons as himself. Pirate Stew! Pirate Stew! Medal-winner Chris Riddell. CHRIS RIDDELL Pirate Stew for me and you! is a much-loved illustrator and acclaimed Marvellously silly and gloriously political cartoonist. He has won the Costa entertaining, this tale of babysitting Children’s Book Award, the Nestlé Gold pirates, flying ships, moonlit donut Award, and is the only artist to have won the Kate Greenaway Medal three times, feasts and the legendary pirate stew most recently for his illustrations in The Sleeper is told in irresistible, swashbuckling and the Spindle. -

Great Beginnings

GREAT BEGINNINGS Bala Cynwyd and Welsh Valley Middle Schools Suggested Summer Reading 2017 Greetings Parents! Reading is very important to your students’ futures. The higher their level of literacy, the greater the opportunities they will have in education. Please keep your child reading this summer by checking out the summer reading clubs at your local public library or by using the attached suggested summer reading list. The attached summer reading list may help you and your child pick out good books. As librarians, we feel the most important part of our job is matching the right book with the right reader. Since we won’t be able to personally provide this assistance over the summer, we are doing the next best thing. We are providing you with a list of “sure- reads.” These books have such great opening lines that readers will immediately be hooked! Much of this list was compiled from student and teacher suggestions as well as professional journals. Many of the genres are represented. If your child gets hooked on an author, you may want to check out other titles by that same author! The list is alphabetical by author’s last name. Book summaries are provided compliments of the publishers on the Library’s online public access catalog DESTINY. You can find Destiny by going to www.lmsd.org. Select Quick Links, Library Pages, your school, and Destiny in the upper left hand corner. Also available on the District’s web page are the 2018 Reading Olympic titles for middle school readers. Please remember that we have not personally read each book on the list or all of the books by each author. -

100 Books to Try and Read in Year 3/4

100 Books To Try And Read In Year 3/4 The Accidental Prime The Wild Robot Minister Ottoline and the Yellow Smile Dragons at Crumbling That Pesky Rat There May Be A Castle Cat Peter Brown Castle Tom McLaughlin Geraldine McCaughrean Lauren Child Terry Pratchett Chris Riddell Piers Torday The Shrimp Frindle The Year of Billy Miller Mouse Noses on The Invention of Huge Shackleton’s Fergus Crane Toast Cabret Journey Andrew Clements Emily Smith Kevin Henkes Paul Stewart and Chris Brian Selznick William Grill Riddell Darren Fletcher The Tale of Despereaux The Whisperer Kate DiCamillo Nick Butterworth 100 Books To Read In Year 3 and 4 Charlie and the The Butterfly Lion Chocolate Factory The Iron Man Varjak Paw Stuart Little The Battle of Bubble and War Game Squeak Roald Dahl Michael Morpurgo Ted Hughes E B White Michael Foreman S F Said Phillips Pearce Diary Of A Wimp Kid The Railway Children The Yearling The Firework-Maker’s A Little Princess The Last Castaways Surf’s Up Daughter Jeff Kinney E Nesbit Marjorie Kinnan Frances Hodgson Harry Horse Rawlings Kwame Alexander Phillip Pullman Burnett The Legend of Captain My Headteacher is a Horrid Henry A Child Of Books Malkin Moonlight Alison Hubble The Worst Witch Vampire Rat Crow’s Teeth Francesca Simon Oliver Jeffers Emma Cox Allan Ahlberg and Bruce Jill Murphy Pamela Butchart Ingham Eoin Colfer 100 Books To Read In Year 3 and 4 Billionaire Boy Fairy Tales Cliffhanger Oliver and the Seawigs The House That Sailed Krindlekrax Lizzie Dripping Away Terry Jones David Walliams Phillip Reeve Jacqueline