Termination of Personal Health Insurance Contracts by Cancellation Or Nonrenewal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directors Guild of America, Inc. National Commercial Agreement of 2017

DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA, INC. NATIONAL COMMERCIAL AGREEMENT OF 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page WITNESSETH: 1 ARTICLE 1 RECOGNITION AND GUILD SHOP 1-100 RECOGNITION AND GUILD SHOP 1-101 RECOGNITION 2 1-102 GUILD SHOP 2 1-200 DEFINITIONS 1-201 COMMERCIAL OR TELEVISION COMMERCIAL 4 1-202 GEOGRAPHIC SCOPE OF AGREEMENT 5 1-300 DEFINITIONS OF EMPLOYEES RECOGNIZED 1-301 DIRECTOR 5 1-302 UNIT PRODUCTION MANAGERS 8 1-303 FIRST ASSISTANT DIRECTORS 9 1-304 SECOND ASSISTANT DIRECTORS 10 1-305 EXCLUSIVE JURISDICTION 10 ARTICLE 2 DISPUTES 2-101 DISPUTES 10 2-102 LIQUIDATED DAMAGES 11 2-103 NON-PAYMENT 11 2-104 ACCESS AND EXAMINATION OF BOOKS 11 AND RECORDS ARTICLE 3 PENSION AND HEALTH PLANS 3-101 EMPLOYER PENSION CONTRIBUTIONS 12 3-102 EMPLOYER HEALTH CONTRIBUTIONS 12 i 3-103 LOAN-OUTS 12 3-104 DEFINITION OF SALARY FOR PENSION 13 AND HEALTH CONTRIBUTIONS 3-105 REPORTING CONTRIBUTIONS 14 3-106 TRUST AGREEMENTS 15 3-107 NON-PAYMENT OF PENSION AND HEALTH 15 CONTRIBUTIONS 3-108 ACCESS AND EXAMINATION OF BOOKS 16 RECORDS 3-109 COMMERCIAL INDUSTRY ADMINISTRATIVE FUND 17 ARTICLE 4 MINIMUM SALARIES AND WORKING CONDITIONS OF DIRECTORS 4-101 MINIMUM SALARIES 18 4-102 PREPARATION TIME - DIRECTOR 18 4-103 SIXTH AND SEVENTH DAY, HOLIDAY AND 19 LAYOVER TIME 4-104 HOLIDAYS 19 4-105 SEVERANCE PAY FOR DIRECTORS 20 4-106 DIRECTOR’S PREPARATION, COMPLETION 20 AND TRAVEL TIME 4-107 STARTING DATE 21 4-108 DIRECTOR-CAMERAPERSON 21 4-109 COPY OF SPOT 21 4-110 WORK IN EXCESS OF 18 HOURS 22 4-111 PRODUCTION CENTERS 22 ARTICLE 5 STAFFING, MINIMUM SALARIES AND WORKING CONDITIONS -

Img Signature Travel Insurancesm

IMG SIGNATURE TRAVEL INSURANCESM BENEFITS SIGNATURE TRAVEL INSURANCE BENEFITS SIGNATURE TRAVEL INSURANCE Available – if purchased within 20 days of initial trip Trip Cancellation Trip cost insured (up to $100,000) Pre-existing Condition Waiver payment Trip Interruption 150% of trip cost insured Common Carrier AD&D Up to $100,000 Travel Delay Up to $1,000 ($250 per day max after delay of 6 hrs) Search & Rescue Up to $10,000 Missed Connection Up to $500 (after a delay of 3 hours) Sports Equipment Rental Up to $2,000 ($500 Day Max) Change Fee Up to $300 Waives excluded sports/ Included Reimbursement of Miles or recreation activities Up to $75 Reward Points Rental Car Damage Up to $40,000 Lost/Baggage Up to $2,500 Coverage Type Primary Baggage Delay Up to $500 Cancel for Any Reason Up to 75% of the trip cost insured if purchased Emergency Medical Up to $100,000 (UPGRADE) within 20 days of initial trip payment Interrupt for Any Reason Up to 75% of the trip cost insured Emergency Dental Up to $1,000 (UPGRADE) TRAVEL COVERAGE BAGGAGE & EQUIPMENT COVERAGE TRIP CANCELLATION/INTERRUPTION BAGGAGE AND PERSONAL EFFECTS You can be reimbursed for unused travel arrangements, as well as up to $75 for fees If your baggage or personal effects are lost, stolen or damaged, we will cover the to rebank frequent flyer miles, for reasons such as death or covered sickness or injury loss or cost of repair. If your baggage is delayed for more than 24 hours after you of you, family member, traveling companion, business partner or child caregiver; being reach your -

Cancellation Claim Form

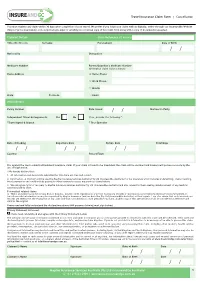

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cancellation You must register any claim within 30 days after completion of your travel. We prefer if you lodge your claim with us digitally, either through our InsureandGo Website (https://quote.insureandgo.com.au/policylogin.aspx) or emailing us a scanned copy of this claim form along with a copy of documents requested. Claimant Details Claim Reference (if known) Title (Mr/Mrs etc) Surname Forename(s) Date of Birth / / Nationality Occupation Medicare Number Parent/Guardian’s Medicare Number (If medical claim is for a minor) Home Address ' Home Phone ' Work Phone ' Mobile State Postcode Email Policy Details Policy Number Date Issued / / Number in Party Independent Travel Arrangements: Yes No If no, provide the following *: *Travel Agent & Branch * Tour Operator Date of Booking Departure Date Return Date Total Days / / / / / / Country Resort/Town It is against the law to submit a fraudulent insurance claim. If your claim is found to be fraudulent the claim will be declined and Insurers will pursue recovery by the use of legal action. I/We hereby declare that: 1. All information and documents submitted for this claim are true and correct. 2. Information on this form will be used by Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) for my insurance which includes underwriting, claims handling, fraud prevention and could include passing to other insurers to access my previous claims history. 3. We subrogate rights of recovery to Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) and also consent to them seeking reimbursement of any medical expenses paid by them. For medical related claims: 4. -

Trip Cancellation/Interruption Claim Form

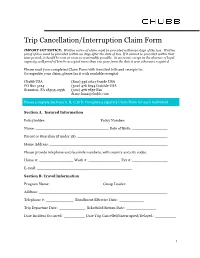

Trip Cancellation/Interruption Claim Form IMPORTANT NOTICE: Written notice of claim must be provided within 90 days of the loss. Written proof of loss must be provided within 90 days after the date of loss. If it cannot be provided within that time period, it should be sent as soon as reasonably possible. In no event, except in the absence of legal capacity, will proof of loss be accepted more than one year from the date it was otherwise required. Please mail your completed Claim Form with itemized bills and receipts to: (to expedite your claim, please fax it with readable receipts) Chubb USA (800) 336 0627 Inside USA PO Box 5124 (302) 476 6194 Outside USA Scranton, PA 18505-0556 (302) 476 7857 Fax [email protected] Please complete Sections A, B, C, & D. Complete a separate Claim Form for each individual. Section A. Insured Information Policyholder: Policy Number: Name: Date of Birth: Parent or Guardian (if under 18): Home Address: Please provide telephone and facsimile numbers, with country and city codes. Home #: Work #: Fax #: E-mail: Section B. Travel Information Program Name: Group Leader: Address: Telephone #: Enrollment Effective Date: Trip Departure Date: Scheduled Return Date: Date Incident Occurred: Date Trip Cancelled/Interrupted/Delayed: 1 Section C. Reason for Claim (provide additional pages if necessary): Section D. Physician or Provider Name of physician or provider: Phone #: Address: Diagnosis or nature of illness or injury: Date of illness (first symptom) or injury: Date first consulted for this condition: Hospital -

1 United States Fire Insurance Company

United States Fire Insurance Company Administrative Office: 5 Christopher Way, Eatontown, NJ 07724 (Hereinafter referred to as “the Company”) TRAVEL PROTECTION PLAN This Certificate of Insurance describes the insurance benefits underwritten by United States Fire Insurance Company, herein referred to as the Company and also referred to as We, Us and Our. The insurance benefits vary from program to program. Please refer to the accompanying Confirmation of Benefits, which provides the Insured, also referred to as You or Your, with specific information about the program You purchased. You should contact the Company immediately if You believe that the Confirmation of Benefits is incorrect. Signed for United States Fire Insurance Company By: Marc J. Adee Chairman and CEO Insurance provided by this Certificate is subject to all of the terms and conditions of the Group Policy. If there is a conflict between the Policy and this Certificate, the Policy will govern. If You are not satisfied for any reason, You may return Your Certificate to Travel Insurance Services within 15 days after receipt. Your premium will be refunded, provided You have not already departed on the Trip or filed a claim. When so returned, the coverage under the Certificate is void from the beginning. Renewal: Coverage under this Certificate is not renewable. SHORT TERM COVERAGE NON-RENEWABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS SCHEDULE OF BENEFITS SECTION I. COVERAGES SECTION II. DEFINITIONS SECTION III INSURING PROVISIONS SECTION IV. GENERAL EXCLUSIONS SECTION V. GENERAL PROVISIONS SECTION VI COORDINATION OF BENEFITS SCHEDULE OF BENEFITS Maximum Benefit Amount/Principal Sum Part A – Travel Arrangement Protection Trip Cancellation ................................................... -

DB MF PW RCSTD 0314.Pdf

DB/MF/PW/RCSTD/0314 10 things to do before you go Important 1. Check the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) travel Under the new travel directive from the European Union (EU), advice online at www.gov.uk/knowbeforeyougo. you are entitled to claim compensation from your airline if any of the following happen. 2. Get travel insurance and check that the cover is appropriate. 1. You are not allowed to board or your flight is cancelled. If you check-in on time but you are not allowed to board 3. Get a good guidebook and get to know the place you are because there are too many passengers for the number of going to. Find out about local laws and customs. seats available or your flight is cancelled, the airline operating the flight must offer you financial compensation. 4. Make sure you have a valid passport and any visas you need. 2. There are long delays. If you are delayed for two hours or more, the airline must 5. Check what vaccinations you need at least six weeks before offer you meals and refreshments, hotel accommodation you go. and communication facilities. If you are delayed for more than five hours, the airline must also offer to refund your 6. Check to see if you need to take extra health precautions ticket. (visit www.nhs.uk/travelhealth) 3. Your baggage is damaged, lost or delayed. 7. Make sure whoever you book your trip through is a If your checked-in baggage is damaged or lost by an EU member of the Association of British Travel Agents (ABTA) airline, you must make a claim to the airline within seven or the Air Travel Organisers' Licensing scheme (ATOL). -

Property and Casualty Insurance

CHAPTER 26.1-39 PROPERTY AND CASUALTY INSURANCE 26.1-39-01. Rescission of fire insurance contract for alteration increasing risk. An alteration in the use or condition of a thing insured from that to which it is limited by the policy, if made without the consent of the insurer, by means within the control of the insured, and if it increases the risk, entitles an insurer to rescind a fire insurance contract. 26.1-39-02. Rescission of fire contract not permitted if risk not increased. An alteration in the use or condition of a thing insured from that to which it is limited by the policy, which does not increase the risk, does not affect a fire insurance contract. 26.1-39-03. When fire contract unaffected though risk increased. A fire insurance contract is not affected by any act of the insured subsequent to the execution of the policy, if the act does not violate its provisions, even though it increases the risk and is the cause of a loss. 26.1-39-04. Measure of indemnity on fire policy. If there is no valuation in the policy, the measure of indemnity in an insurance against fire is the full amount stated in the policy. If there is a valuation in the policy, the valuation is conclusive between the parties in the adjustment either of a partial or a total loss if the insured has some interest at risk and there is no fraud on the insured's part. In the event of a partial loss, the insurer is liable only for the proportion of the amount insured as the loss bears to the value of the whole interest of the insured in the property insured. -

Appointments – Cancellation and NO Show Policy Lattimore Physical

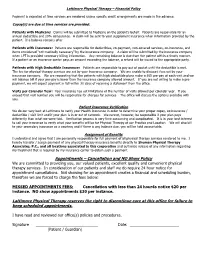

Lattimore Physical Therapy – Financial Policy Payment is expected at time services are rendered unless specific credit arrangements are made in the advance. Copay(s) are due at time services are provided. Patients with Medicare: Claims will be submitted to Medicare on the patient’s behalf. Patients are responsible for an annual deductible and 20% coinsurance. A claim will be sent to your supplement insurance when information provided by the patient. If a balance remains after Patients with Insurance: Patients are responsible for deductibles, co-payment, non-covered services, co-insurance, and items considered “not medically necessary” by the insurance company. A claim will be submitted by the insurance company when LPT is provided necessary billing information. Any remaining balance is due from the patient within a timely manner. If a patient or an insurance carrier pays an amount exceeding the balance, a refund will be issued to the appropriate party. Patients with High Deductible Insurance: Patients are responsible to pay out of pocket until the deductible is met. The fee for physical therapy services are set by your insurance company. We are unable to discount fees set by your insurance company. We are requesting that the patients with high deductible plans make a $65 pre-pay at each visit and we will balance bill if your pre-pay is lower than the insurance company allowed amount. If you are not willing to make a pre- payment, we will expect payment in full within 30 days of receiving a statement from the office. Visits per Calendar Year: Your insurance has set limitations of the number of visits allowed per calendar year. -

Trip Cancellation Claims Form

MAPFRE|INSURANCE® – Trip Cancellation Claims Form MAPFRE|INSURANCE® Date: Claim Form c/o InsureandGo USA 7300 Corporate Center Drive Suite 601 Miami, FL 33126 Claim No.: Trip Cancellation Name of Insured Home Address State City Zip Home Telephone Date Of Birth Cell Phone E-mail Address Mailing Address, if different from Home Address: Street Address State City Zip Plan Information/ Trip Information Policy # Date Incident Occurred Departure Date Return Date Original Destination Travel Agency Name Date of Initial Travel Agency Phone # Deposit/Payment Traveling Companions (Please indicate name and relationship to you) 1. 6. 2. 7. 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. TC012015 MAPFRE|INSURANCE® – Trip Cancellation Claims Form Please Complete The Section Below. Documents You Need to Send Us – SEND DOCUMENTS BUT KEEP COPIES FOR YOUR RECORDS The original trip cancellation invoice. If your booking was flight only you may not be able to obtain this document, if this is the case please provide a written statement to this effect from the travel agent. All unused travel tickets, itineraries etc. If cancellation is due to loss of employment we require a letter from your former employer which confirms that you have been terminated and the position you held and your length of service. If cancellation is for medical reasons, including death, the attached medical certificate must be completed by the primary physician of the individual. whose condition has led to the submission of the claim. If cancellation is due to a death we require a certified copy of the death certificate. If the deceased was insured under the policy we require a copy of the Estate letters of administration. -

CHAPTER 69 Department of Insurance

CHAPTER 69 Department of Insurance (Statutory Authority: 1976 Code §§ 1–23–10 et seq., 1–23–110 et seq., 34–29–10 et seq., 34–31–10 et seq., 37–4–101 et seq., 38–1–20(34), 38–3–60, 38–3–110 et seq., 38–5–80, 38–9–180, 38–23–10 et seq., 38–33–10 et seq., 38–33–200, 38–38–550, 38–39–10 et seq., 38–43–10 to 38–43–80, 38–43–100, 38–43–106, 38–43–110, 38–45–50, 38–47–10 et seq., 38–47–40, 38–49–10 et seq., 38–50–90, 38–55–50, 38–57–20 et seq., 38–63–10, 38–65–10, 38–69–10, 38–71–730, 38–73–330, 38–73–730, 38–73–735, 38–73–760, 38–77–530, 38–78–110 1975 Act No. 306) 69–1. Adjustment of Claims Under Unusual Circumstances. (Statutory Authority: 1976 Code Sections 1–23–110 et seq., 38–3–110 et seq., and 38–49–20 et seq.) 1. Licensed Adjusters or motor vehicle physical damage appraisers in South Carolina are author- ized to adjust claims or appraise automobiles under the physical damage insurance coverage for unlicensed companies under the following circumstances: (a) Where the insured has an accident in South Carolina but is not a resident, being in a status of a transient. (b) Where the insured is a new resident in the State and has an unexpired policy of an unlicensed company purchased before he moved into the State. -

Shelter Cares 280 Hours

Contact Shelter Insurance® at: 1-800-SHELTER (743-5837) • ShelterInsurance.com www.facebook.com/ShelterInsurance www.youtube.com/user/ShelterInsurance1 twitter.com/Shelter_ins www.linkedin.com/company/shelter-insurance-companies 2013 Overview Table of Contents To Our Policyholders ................................................................1 Our Commitment to Management Excellence ...........................2 2013 in Review ....................................................................3-11 Companywide Information .....................................................12 Family of Companies ..............................................................13 Financial Results ................................................................14-25 Directors and Officers .............................................................26 Community Involvement ...................................................27-32 dfg Shelter Gardens We’re your Shield. We’re your Shelter. To Our Policyholders We wish to begin this annual report by thanking retired board member Gerald Brouder for his years of service to Shelter Insurance® and extending our best wishes to his successor, David Monday. For 2013, moderate catastrophe losses, elevated average premium per policy, improved policy retention, and solid invest- ment returns resulted in $135 million of combined income before tax for the Shelter Insurance Companies. Total gross property and casualty premiums written approached nearly $1.5 billion, policyholders’ surplus increased 12.1% and grew to over -

915-1 Improper Termination Practices Model Act

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—January 2001 IMPROPER TERMINATION PRACTICES MODEL ACT Section 1. Purpose Section 2. Scope Section 3. Definitions Section 4. Termination Provisions Section 5. Unfair Discrimination in Termination Provisions Section 6. Termination of Lines of Insurance Section 7. Rescission Section 8. Notice of Cancellation Section 9. Cancellation—Reasons Section 10. Time for Repairs or Rehabilitation Prior to Cancellation Section 11. Refund of Premium Upon Cancellation Section 12. Notice of Renewal or Nonrenewal Section 13. Liability of Insurers or Producers Regarding Statements Made in Notices or Information Section 14. Notice to Insured as to Eligibility for Residual Market Mechanism Coverage Section 15. Notice; Right to Appeal Section 16. Improper Termination—Appeal Section 17. Proof of Mailing Section 18. Improper Termination Practice—Definition; Hearing Section 19. Improper Termination Practice—Penalty Section 20. Separability Provision Section 1. Purpose The purpose of this Act is to protect policyholders from improper terminations of insurance coverage and to set forth standards for the regulation and disposition of terminations of policies or certificates of insurance. Nothing in this Act shall be construed to create or imply a private cause of action for violation of this Act except that a named insured may appeal the termination of the named insured’s policy pursuant to Section 16. Section 2. Scope This Act shall apply to all insurers issuing or renewing in this state any policy or certificate of insurance as defined in Section 3I. Section 3. Definitions For the purposes of this Act: A. “Cancellation” or “canceled” means the termination of a policy by an insurer prior to the expiration date of the policy.