Norse Naming Elements in Shetland and Faroe: a Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

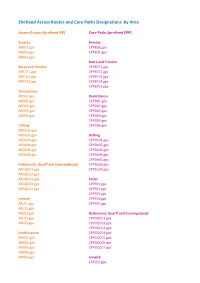

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

BURRA and TRONDRA COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES a Virtual Meeting of the Above Community Council Was Held on Zoom on Monday 24Th August 2020 at 7Pm

Minute subject to approval at the next Community Council Meeting BURRA AND TRONDRA COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES A virtual meeting of the above Community Council was held on Zoom on Monday 24th August 2020 at 7pm. Present Mr. N. O’Rourke Mr. G. Laurenson Miss N. Fullerton Mrs M. Garnier Ms. G. Hession Apologies Miss A. Williamson Mr. B. Adamson Mr. R. Black Mr. Michael Duncan, SIC Mrs. Roselyn Fraser, SIC In Attendance Mrs. J. Adamson (Clerk) Cllr. M. Lyall Cllr. I Scott 1. MINUTES OF LAST MEETING The Minutes of 21st July 2020 were approved by Gary Laurenson and Mhairi Garnier. 2. MATTERS ARISING (a) War Memorial, Bridge End – Grant for repairs Further photographs were submitted to accompany our Grants pre-application form to the War Memorial Trust back in March and they acknowledged receipt by e-mail on 4th March. They advised that the enquiry would undergo a preliminary assessment but due to the volume of work facing the charity they said it may take up to two months before they can provide us with a response. They asked that we do not contact them to chase our enquiry within the next 8 weeks and they will reply as soon as possible but could not guarantee any timeframes. (Our reference No is WMO/153611.) Nothing further had been heard from them. (b) Streetlights – Brough Mervyn Smith, SIC, advised by e-mail on 1st October 2019 that these two columns are scheduled for replacement next financial year (2020/21). It was agreed that this would be kept on the minutes until this is done. -

Delting Community Council

Delting Community Council MINUTES OF A MEETING HELD ON THURSDAY 24TH SEPTEMBER 2020 – Due to the coronavirus pandemic, this was a virtual meeting held through FaceTime. 2020/09/01 MEMBERS Mr A Cooper, Chairman Ms J Dennison Mr A Hall Mr J Milne Mr B Moreland 2020/09/02 IN ATTENDANCE Ms A Arnett, SIC Community Planning and Development Mrs A Foyle, Clerk 2020/09/03 CIRCULAR The circular calling the meeting was held as read. 2020/09/04 APOLOGIES Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Ms R Griffiths, Mr W Whirtow, Mrs E Macdonald and Mr M Duncan. 2020/09/05 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING The Minutes of the meeting held on 27th August 2020 were approved by Mr B Moreland and seconded by Ms J Dennison. 2020/09/06 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 2020/09/07 MATTERS ARISING 7.1 Muckle Roe Road – Improvements – Ms J Dennison reported that there is not much changed since the last meeting. The loose chippings signs have been taken down but the road has not been swept. They are still waiting for passing place signs. 7.2 School Transport Issue – Mossbank service not fitting in with the school times – The Chairman said there is no further update on this at the moment. 7.3 Digital Highlands and Islands – Broadband Rollout – The Chairman said that the SIC Development Committee have approved the project seeking specialist advice for a long term solution by March next year. The SIC will receive the report by the end of March which will help us know who is in nought spots and people will be able to see what the options are. -

Download Download

SCULI'Tl/KED SLAB FRO ISLANE MTH BVKKA,F DO SHETLAND9 19 . ir. NOTIC A SCULPTURE F O E D SLAB FROE ISLANTH M F BURRADO , SHETLAND GILBERY B . T GOUDIE, F.S.A. SCOT. This unique monument, now safely deposited in the Museum of the Society, camo under my eye in the course of investigations which I made in the Burra Isles on the occasion of a visit to Shetland in the month of July 1877. Eichly sculpture wits i t wheel-croshi a s da f eleganso t design, with interlaced ornamentation of Celtic pattern, and a variety of figure subjects carefull ye ranke b executedy dma amont i , e foremosth g n i t interese Sculptureth f o t d Stone f Scotland o t si lay s , A wite . th h decorated side uppermost shora t a ,t distanc e churce soutth th f ho o eht in the ancient churchyard at Papil, it might have been noticed at any time by any one who chose to look for it, or who, chancing to observe it, had recognised its significanc a reli f s Christiao a ce t froar n ma perio f o d remote antiquity. But from age to age it appears to have escaped notice. Th Statisticaw e parisNe e th h l d clergymeAccountan d wroto Ol e snwh e th distric e e yearoth fth n si t 179 184d 9an 1 respectively, see havmo t e been unawar y othes existencit an rf f o o esculpture r o e d t i remains s i r no , noticed by any authors, natives or strangers, who have published accounts of the country from time to time, though the site is of more than ordinary interest ecclesiologically, from the fact of its having been occupied formerly by one of the towered churches of the north, of which that on the island of Egilsa Orknen y i e onlth ys y i preserved specimen s wila , l afterwards shown.e stonb e pass Th ha et memory marke e restindth ge placth f o e members of the family of Mr John Inkster, Baptist missionary in the island case s usua f th sucA eo n .i lh beed relicsha n t i regarde, n a s da importation t soma , e unknown period, from East.e "th " Beyond thio sn traditional idea appear havo st e been preserved regardin. -

Folklore, Folk Belief, and the Selkie

Supernatural Beings in the Far North: Folklore, Folk Belief, and The Selkie NANCY CASSELL MCENTIRE Within the world of folklore, stories of people turning into animals are well known. Either by accident or by design, a person may become a malevolent wolf, a swan, a helpful bird, a magic seal, a dog, a cat. Sometimes these stories are presented as folktales, part of a fictitious, make-believe world. Other times they are presented as legends, grounded in a narrator’s credibility and connected to everyday life. They may be sung as ballads or their core truths may be implied in a familiar proverb. They also affect human behavior as folk belief. Occasionally, sympathetic magic is involved: the human imagination infers a permanent and contiguous relationship between items that once were either in contact or were parts of a whole that later became separated or transformed. A narrative found in Ireland, England, and North America depicts a man who spends a night in a haunted mill, where he struggles with a cat and cuts off the cat’s paw. In the morning, the wife of a local villager has lost her hand (Baughman: 99; Disenchantment / Motif no. D702.1.1). France, French-speaking Canada and French-speaking Louisiana have stories of the loup-garou, a shape- shifter who is a person trapped in the body of an animal. One might suspect that he or she has encountered a loup-garou if that the animal is unusually annoying, provoking anger and hostile action. One penetrating cut will break the spell that has kept it trapped in animal form. -

2200022200 Vviiisssiiiooonn

22002200 VViissiioonn ooff SShheettllaanndd’’ss HHeeaalltthhccaarree Fitting together a vision of future health and care services in Shetland NHS Shetland 2020 Vision April 2005 ii NHS SHETLAND 2020 VISION CONTENTS List of Figures & Boxes . iii List of Appendices . iv Acknowledgements . iv Abbreviations . v Executive Summary . vi Section A Introduction & Background 1 A.1 Introduction to NHS Shetland’s 2020 Vision Project . 2 A.2 Strategic Direction for 2020 – outcomes of 2020 Vision Phase 1 . 3 A.3 Introduction to Shetland . 6 A.4 Profile of Shetland Health and Healthcare . 17 A.5 Drivers for change for future Shetland Healthcare . 23 Section B Key Themes for 2020 29 B.1 National Direction . 31 B.2 Shetland Public . 36 B.3 Safety & Quality . 41 B.4 Workforce . 48 B.5 Transport . 59 B.6 Facilities . 67 B.7 Medical Technologies . 71 B.8 Information & Communication Technologies . 75 Section C Shetland Services 2020 81 C.1 Health Improvement . 84 C.2 Disability Services . 95 C.3 Community Health Services . 99 C.4 General Practice . 104 C.5 Mental Health Services . 113 C.6 Dental Services . 117 C.7 Pharmacy Services . 121 C.8 Child Health Services . 124 C.9 Older People’s Services . 131 C.10 Alcohol & Drugs Services . 137 C.11 Clinical Support Services . 144 C.12 Maternity Services . 149 C.13 Hospital Surgical Services . 153 C.14 Hospital Medical Services . 162 C.15 Cancer Services . 170 Section D Our 2020 Vision of Shetland Healthcare 177 Section E Recommendations 185 Appendices . 191 NHS SHETLAND 2020 VISION iii LIST OF FIGURES & BOXES Section A Introduction & Background Box A1 Objectives for Future Healthcare Delivery in Shetland . -

Shetland Islands Visitor Survey 2019 Shetland Islands Council and Visitscotland April 2020 Contents

Shetland Islands Visitor Survey 2019 Shetland Islands Council and VisitScotland April 2020 Contents Project background Trip profile Objectives Visitor experience Method and analysis Volume and value Visitor profile Summary and conclusions Visitor journey 2 Project background • Tourism is one of the most important economic drivers for the Shetland Islands. The islands receive more than 75,000 visits per year from leisure and business visitors. • Shetland Islands Council has developed a strategy for economic development 2018-2022 to ensure that the islands benefit economically from tourism, but in a way that protects its natural, historical and cultural assets, whilst ensuring environmental sustainability, continuous development of high quality tourism products and extending the season. • Strategies to achieve these objectives must be based on sound intelligence about the volume, value and nature of tourism to the islands, as well as a good understanding of how emerging consumer trends are influencing decisions and behaviours, and impacting on visitors’ expectations, perceptions and experiences. • Shetland Islands Council, in partnership with VisitScotland, commissioned research in 2017 to provide robust estimates of visitor volume and value, as well as detailed insight into the experiences, motivations, behaviours and perceptions of visitors to the islands. This research provided a baseline against which future waves could be compared in order to identify trends and monitor the impact of tourism initiatives on the islands. This report details -

The Nicolsons”, Published in West Highland Notes & Queries, Ser

“1467 MS: The Nicolsons”, published in West Highland Notes & Queries, ser. 4, no. 7 (July. 2018), pp. 3–18 1467 MS: The Nicolsons The Nicolsons have been described as ‘the leading family in the Outer Hebrides towards the end of the Norse period’, but any consideration of their history must also take account of the MacLeods.1 The MacLeods do not appear on record until 1343, when David II granted two thirds of Glenelg to Malcolm son of Tormod MacLeod of Dunvegan, and some lands in Assynt to Torquil MacLeod of Lewis;2 nor do they appear in the 1467 MS, which the late John Bannerman described as ‘genealogies of the important clan chiefs who recognised the authority of the Lords of the Isles c. 1400’.3 According to Bannerman’s yardstick, either the MacLeods had failed to recognise the authority of the lords of the Isles by 1400, or they were simply not yet important enough to be included. History shows that they took the place of the Nicolsons, who are not only included in the manuscript, but given generous space in the fourth column (NLS Adv. ms 72.1.1, f. 1rd27–33) between the Mathesons and Gillanderses, both of whom are given much less. It seems that the process of change was far from over by 1400. The circumstances were these. From c. 900 to 1266 Skye and Lewis belonged to the Norse kingdom of Man and the Isles. During the last century of this 366- year period, from c. 1156, the Norse-Gaelic warrior Somerled and his descendants held the central part of the kingdom, including Bute, Kintyre, Islay, Mull and all the islands as far north as Uist, Barra, Rum, Eigg, Muck and Canna.