Part Ii Shetland Boats and Their Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northmavine the Laird’S Room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson

Northmavine The Laird’s room at the Tangwick Haa Museum Tom Anderson Tangwick Haa All aspects of life in Northmavine over the years are Northmavine The wilds of the North well illustrated in the displays at Tangwick Haa Museum at Eshaness. The Haa was built in the late 17th century for the Cheyne family, lairds of the Tangwick Estate and elsewhere in Shetland. Some Useful Information Johnnie Notions Accommodation: VisitShetland, Lerwick, John Williamson of Hamnavoe, known as Tel:01595 693434 Johnnie Notions for his inventive mind, was one of Braewick Caravan Park, Northmavine’s great characters. Though uneducated, Eshaness, Tel 01806 503345 he designed his own inoculation against smallpox, Neighbourhood saving thousands of local people from this 18th Information Point: Tangwick Haa Museum, Eshaness century scourge of Shetland, without losing a single Shops: Hillswick, Ollaberry patient. Fuel: Ollaberry Public Toilets: Hillswick, Ollaberry, Eshaness Tom Anderson Places to Eat: Hillswick, Eshaness Another famous son of Northmavine was Dr Tom Post Offices: Hillswick, Ollaberry Anderson MBE. A prolific composer of fiddle tunes Public Telephones: Sullom, Ollaberry, Leon, and a superb player, he is perhaps best remembered North Roe, Hillswick, Urafirth, for his work in teaching young fiddlers and for his role Eshaness in preserving Shetland’s musical heritage. He was Churches: Sullom, Hillswick, North Roe, awarded an honorary doctorate from Stirling Ollaberry University for his efforts in this field. Doctor: Hillswick, Tel: 01806 503277 Police Station: Brae, Tel: 01806 522381 The camping böd which now stands where Johnnie Notions once lived Contents copyright protected - please contact Shetland Amenity Trust for details. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the contents are accurate, the funding partners do not accept responsibility for any errors in this leaflet. -

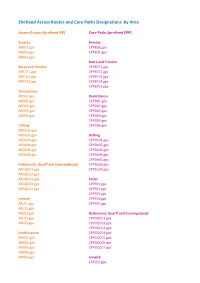

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Codes by Area

Shetland Access Routes and Core Paths Designations by Area Access Routes (prefixed AR) Core Paths (prefixed CPP) Bressay Bressay ARB01.gpx CPPB01.gpx ARB02.gpx CPPB02.gpx ARB03.gpx Burra and Trondra Burra and Trondra CPPBT01.gpx ARBT01.gpx CPPBT02.gpx ARBT02.gpx CPPBT03.gpx ARBT03.gpx CPPBT04.gpx CPPBT05.gpx Dunrossness ARD01.gpx Dunrossness ARD03.gpx CPPD01.gpx ARD04.gpx CPPD02.gpx ARD05.gpx CPPD03.gpx ARD06.gpx CPPD04.gpx CPPD05.gpx Delting CPPD06.gpx ARDe01.gpx ARDe02.gpx Delting ARDe03.gpx CPPDe01.gpx ARDe04.gpx CPPDe02.gpx ARDe06.gpx CPPDe03.gpx ARDe08.gpx CPPDe04.gpx CPPDe05.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh CPPDe06.gpx ARGQC01.gpx CPPDe07.gpx ARGQC02.gpx ARGQC03.gpx Fetlar ARGQC04.gpx CPPF01.gpx ARGQC05.gpx CPPF02.gpx CPPF03.gpx Lerwick CPPF04.gpx ARL01.gpx CPPF05.gpx ARL02.gpx ARL03.gpx Gulberwick, Quarff and Cunningsburgh ARL04.gpx CPPGQC01.gpx ARL05.gpx CPPGQC02.gpx CPPGQC03.gpx Northmavine CPPGQC04.gpx ARN01.gpx CPPGQC05.gpx ARN02.gpx CPPGQC06.gpx ARN03.gpx CPPGQC07.gpx ARN04.gpx ARN05.gpx Lerwick CPPL01.gpx Nesting and Lunnasting CPPL02.gpx ARNL01.gpx CPPL03.gpx ARNL02.gpx CPPL04.gpx ARNL03.gpx CPPL05.gpx CPPL06.gpx Sandwick ARS01.gpx Northmavine ARS02.gpx CPPN01.gpx ARS03.gpx CPPN02.gpx ARS04.gpx CPPN03.gpx CPPN04.gpx Sandsting and Aithsting CPPN05.gpx ARSA04.gpx CPPN06.gpx ARSA05.gpx CPPN07.gpx ARSA07.gpx CPPN08.gpx ARSA10.gpx CPPN09.gpx CPPN10.gpx Scalloway CPPN11.gpx ARSC01.gpx CPPN12.gpx ARSC02.gpx CPPN13.gpx Skerries Nesting and Lunnasting ARSK01.gpx CPPNL01.gpx CPPNL03.gpx Tingwall, Whiteness and Weisdale CPPNL04.gpx -

Delting Community Council

Delting Community Council MINUTES OF A MEETING HELD ON THURSDAY 24TH SEPTEMBER 2020 – Due to the coronavirus pandemic, this was a virtual meeting held through FaceTime. 2020/09/01 MEMBERS Mr A Cooper, Chairman Ms J Dennison Mr A Hall Mr J Milne Mr B Moreland 2020/09/02 IN ATTENDANCE Ms A Arnett, SIC Community Planning and Development Mrs A Foyle, Clerk 2020/09/03 CIRCULAR The circular calling the meeting was held as read. 2020/09/04 APOLOGIES Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Ms R Griffiths, Mr W Whirtow, Mrs E Macdonald and Mr M Duncan. 2020/09/05 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING The Minutes of the meeting held on 27th August 2020 were approved by Mr B Moreland and seconded by Ms J Dennison. 2020/09/06 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest. 2020/09/07 MATTERS ARISING 7.1 Muckle Roe Road – Improvements – Ms J Dennison reported that there is not much changed since the last meeting. The loose chippings signs have been taken down but the road has not been swept. They are still waiting for passing place signs. 7.2 School Transport Issue – Mossbank service not fitting in with the school times – The Chairman said there is no further update on this at the moment. 7.3 Digital Highlands and Islands – Broadband Rollout – The Chairman said that the SIC Development Committee have approved the project seeking specialist advice for a long term solution by March next year. The SIC will receive the report by the end of March which will help us know who is in nought spots and people will be able to see what the options are. -

2200022200 Vviiisssiiiooonn

22002200 VViissiioonn ooff SShheettllaanndd’’ss HHeeaalltthhccaarree Fitting together a vision of future health and care services in Shetland NHS Shetland 2020 Vision April 2005 ii NHS SHETLAND 2020 VISION CONTENTS List of Figures & Boxes . iii List of Appendices . iv Acknowledgements . iv Abbreviations . v Executive Summary . vi Section A Introduction & Background 1 A.1 Introduction to NHS Shetland’s 2020 Vision Project . 2 A.2 Strategic Direction for 2020 – outcomes of 2020 Vision Phase 1 . 3 A.3 Introduction to Shetland . 6 A.4 Profile of Shetland Health and Healthcare . 17 A.5 Drivers for change for future Shetland Healthcare . 23 Section B Key Themes for 2020 29 B.1 National Direction . 31 B.2 Shetland Public . 36 B.3 Safety & Quality . 41 B.4 Workforce . 48 B.5 Transport . 59 B.6 Facilities . 67 B.7 Medical Technologies . 71 B.8 Information & Communication Technologies . 75 Section C Shetland Services 2020 81 C.1 Health Improvement . 84 C.2 Disability Services . 95 C.3 Community Health Services . 99 C.4 General Practice . 104 C.5 Mental Health Services . 113 C.6 Dental Services . 117 C.7 Pharmacy Services . 121 C.8 Child Health Services . 124 C.9 Older People’s Services . 131 C.10 Alcohol & Drugs Services . 137 C.11 Clinical Support Services . 144 C.12 Maternity Services . 149 C.13 Hospital Surgical Services . 153 C.14 Hospital Medical Services . 162 C.15 Cancer Services . 170 Section D Our 2020 Vision of Shetland Healthcare 177 Section E Recommendations 185 Appendices . 191 NHS SHETLAND 2020 VISION iii LIST OF FIGURES & BOXES Section A Introduction & Background Box A1 Objectives for Future Healthcare Delivery in Shetland . -

Shetland Islands Visitor Survey 2019 Shetland Islands Council and Visitscotland April 2020 Contents

Shetland Islands Visitor Survey 2019 Shetland Islands Council and VisitScotland April 2020 Contents Project background Trip profile Objectives Visitor experience Method and analysis Volume and value Visitor profile Summary and conclusions Visitor journey 2 Project background • Tourism is one of the most important economic drivers for the Shetland Islands. The islands receive more than 75,000 visits per year from leisure and business visitors. • Shetland Islands Council has developed a strategy for economic development 2018-2022 to ensure that the islands benefit economically from tourism, but in a way that protects its natural, historical and cultural assets, whilst ensuring environmental sustainability, continuous development of high quality tourism products and extending the season. • Strategies to achieve these objectives must be based on sound intelligence about the volume, value and nature of tourism to the islands, as well as a good understanding of how emerging consumer trends are influencing decisions and behaviours, and impacting on visitors’ expectations, perceptions and experiences. • Shetland Islands Council, in partnership with VisitScotland, commissioned research in 2017 to provide robust estimates of visitor volume and value, as well as detailed insight into the experiences, motivations, behaviours and perceptions of visitors to the islands. This research provided a baseline against which future waves could be compared in order to identify trends and monitor the impact of tourism initiatives on the islands. This report details -

Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – a Dynamic Group Peder Gammeltoft

Shetland and Orkney Island-Names – A Dynamic Group Peder Gammeltoft 1. Introduction Only when living on an island does it become clear how important it is to know one‟s environment in detail. This is no less true for Orkney and Shetland. Being situated in the middle of the North Atlantic, two archipelagos whose land-mass consist solely of islands, holms and skerries, it goes without saying that such features are central, not only to local life and perception, but also to travellers from afar seeking shelter and safe passage. Island, holms and skerries appear to be fixed points in an ever changing watery environment – they appear to be constant and unchanging – also with regard to their names. And indeed, several Scandinavian researchers have claimed that the names of islands constitute a body of names which, by virtue of constant usage and relevance over time, belong among the oldest layers of names (cf. e.g. Hald 1971: 74-75; Hovda 1971: 124-148). Archaeological remains on Shetland and Orkney bear witness to an occupation of these archipelagos spanning thousands of years, so there can be little doubt that these areas have been under continuous utilisation by human beings for a long time, quite a bit longer, in fact, than our linguistic knowledge can take us back into the history of these isles. So, there is nothing which prevents us from assuming that names of islands, holms and skerries may also here carry some of the oldest place-names to be found in the archipelagos. Since island-names are often descriptive in one way or another of the locality bearing the name, island-names should be able to provide an insight into the lives, strategies and needs of the people who eked out an existence in bygone days in Shetland and Orkney. -

Codebook for IPUMS Great Britain 1851-1881 Linked Dataset

Codebook for IPUMS Great Britain 1851-1881 linked dataset 1 Contents SAMPLE: Sample identifier 12 SERIAL: Household index number 12 SEQ: Index to distinguish between copies of households with multiple primary links 12 PERNUM: Person index within household 13 LINKTYPE: Link type 13 LINKWT: Number of cases in linkable population represented by linked case 13 NAMELAST: Last name 13 NAMEFRST: First name 13 AGE: Age 14 AGEMONTH: Age in months 14 BPLCNTRY: Country of birth 14 BPLCTYGB: County of birth, Britain 20 CFU: CFU index number 22 CFUSIZE: Number of people in individuals CFU 23 CNTRY: Country of residence 23 CNTRYGB: Country within Great Britain 24 COUNTYGB: County, Britain 24 ELDCH: Age of eldest own child in household 27 FAMSIZE: Number of own family members in household 27 FAMUNIT: Family unit membership 28 FARM: Farm, NAPP definition 29 GQ: Group quarters 30 HEADLOC: Location of head in household 31 2 HHWT: Household weight 31 INACTVGB: Adjunct occupational code (Inactive), Britain 31 LABFORCE: Labor force participation 51 MARRYDAU: Number of married female off-spring in household 51 MARRYSON: Number of married male off-spring in household 51 MARST: Marital status 52 MIGRANT: Migration status 52 MOMLOC: Mothers location in household 52 NATIVITY: Nativity 53 NCHILD: Number of own children in household 53 NCHLT10: Number of own children under age 10 in household 53 NCHLT5: Number of own children under age 5 in household 54 NCOUPLES: Number of married couples in household 54 NFAMS: Number of families in household 54 NFATHERS: Number of fathers -

Delting Community Council

Delting Community Council MINUTES OF A MEETING HELD IN OLNAFIRTH PRIMARY SCHOOL ON THURSDAY 4TH FEBRUARY 2010 2010/01/01 PRESENT Mr A Cooper, Chairman Mr B Moreland Mr A Hall Mrs B Cheyne Mr D Manson Mr E Nicolson 2010/01/02 IN ATTENDANCE Mr J Dickson Mr D Thomson Mrs A Foyle, Clerk 2010/01/03 CIRCULAR The circular calling the meeting was held as read. 2010/01/04 APOLOGIES Apologies for absence were intimated on behalf of Mr K Hughson, Mr B Couper, Mrs S Bigland, Mrs K McGrath and Mr W Whitrow. 2010/01/05 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING The Minutes from the last meeting were approved on the motion of Mr D Manson and seconded by Mr B Moreland. 2010/01/06 PLANNING APPLICATIONS The following Weekly Lists were made available to Members at the Meeting: 27th November, 4th, 10th and 22nd December 2009. As Mr J Dickson and Mr D Thomson were in attendance to discuss their planning applications, the Chairman welcomed them both to the meeting and brought this agenda item forward. 2010/16/PCD Erect a 2.5kw micro wind turbine on a 6.5m mast, Hvidahus, Brae by James T Dickson. Mr Dickson explained that the main purpose of the wind turbine is to provide heat to the house. The turbine positioned at the front of the property means it will get the wind from the east and west, there will be no flicker effect and it’s the least obtrusive to the neighbours. He went on to say that the noise level is minimal and it’s to be situated 4m from the house and 17m from the road. -

Shetland Craft Trail Other Outlets

Shetland 5 JANE PORTER-JACOBS 9 NINIAN/JOANNA 13 BURRA BEARS 17 JAMES B THOMASON Other Outlets Craft Trail HUNTER KNITWEAR Shetland Arts & Crafts Veer North A BONHOGA GALLERY Wesidale Mill, ZE2 9LW 1 GLANSIN GLASS T 01595 745750 www.shetlandarts.org B GLOBALYELL LTD Contact: Wendy Inkster, Nonavaar, Levenwick, ZE2 9HX 4 Sellafi rth, Yell, ZE2 9DG Snekkarim, North Lea, Meadows Road, Houss, T 01950 422447 80 Commercial Street, Lerwick, www.jamesthomason.co.uk T 01957 744355 Vidlin, ZE2 9QB ZE1 0DL Burra Isle, ZE2 9LE T 01806 577373 T 01595 859374 Payment: cash, cheque www.globalyell.org E [email protected] T 01595 696655 E [email protected] www.vidlinpottery.shetland.co.uk E [email protected] www.burrabears.co.uk Open: 16th May-29th Aug, www.ninianonline.co.uk garden and studio open C Payment: cash, cheque Payment: cash, credit card Payment: cash, cheque Mon 10am-4pm, Sat 10am-2pm HOSWICK VISITORS also by appointment Open: please phone fi rst Open: Mon-Sat 9am-5.30pm, Open: Open most days but please CENTRE My art is about the way I see and call ahead to avoid disappointment Award winning artist. Imaginative, Contact: Cheryl Jamieson, feel about the Shetland landscape. I Ninian o er an exciting collection The original Shetland Teddy fi gurative, Shetland themes, Hoswick, Hoversta, Uyeasound, Unst, work with watercolour, acrylic and of Shetland knitwear, designed by Bear established 1997. Delightful, landscape, portraits, abstracts, Sandwick, ZE2 9HL ZE2 9DL paper collage Joanna Hunter, pop into their shop collectable, handmade bears collage & Australian themes. T 01957 755311 and studio to feast your eyes on T 01950 431284 the exciting array of colours and produced from recycled traditional E [email protected] Fair Isle knitwear. -

The Fouds, Lawrightmen, and Ranselmen of Shetland

FOUDS, LAWRIGHTMEN, AND RANSELMEN OF SHETLAND. 189 IV. E FOUDSTH , LAWRIGHTMEN RANSELMED AN , SHETLANF NO D PARISHES. BY GILBERT GOUDIE, F.S.A. SOOT. e FoudsTh , Lawrightmen d Eanselmean , n constitute machinere dth y of local governmen d justican t n everi e y paris n Shetlandhi . Coming down fro mperioa f undefinedo d antiquity, those Parish Fouds lingered on, latterly disguise Scottise th y db h appellatio f "no Bailie, " until well into last century; the Lawrightmen seem for the most part to disappear from view toward sixteente close th sth f eo hRanselmene centurth d an y; , though som f theeo m dayn e perhap ar surviveow , r ou s o without d a t single representative now living. 1 THE FOUDS. Etymologicall d NortherOl e e Fogeti e Four th th Iceyth n(o f s -di o landic) tongue Fogede th , f Norwayo . That countr presene th t y ya da t contains eighteen counties or Amis, each amt divided into bailiewicks, termed Fogderier or Foudries, in the same way as Shetland was desig- nate a "Foudried e oldeth nn i " time. Eac f theso h e Fogderierr o Foudries is presided over by the Foged, or Sheriff, an official of some consequence who e constantlmw y encounte n countri r y districtn i s Norway appointee Fogeds i e o Th kingth . wh ,s entrustey i , b d d with e maintenancd orderth an e carryinth ,w f judgmentsla o t f eo g ou d an , collectioe th revenuee th Crowne th f morno o f N o se . -

Orkney and Shetland

Orkney and Shetland: A Landscape Fashioned by Geology Orkney and Shetland Orkney and Shetland are the most northerly British remnants of a mountain range that once soared to Himalayan heights. These Caledonian mountains were formed when continents collided around A Landscape Fashioned by Geology 420 million years old. Alan McKirdy Whilst the bulk of the land comprising the Orkney Islands is relatively low-lying, there are spectacular coastlines to enjoy; the highlight of which is the magnificent 137m high Old Man of Hoy. Many of the coastal cliffs are carved in vivid red sandstones – the Old Red Sandstone. The material is also widely used as a building stone and has shaped the character of the islands’ many settlements. The 12th Century St. Magnus Cathedral is a particularly fine example of how this local stone has been used. OrKney A Shetland is built largely from the eroded stumps of the Caledonian Mountains. This ancient basement is pock-marked with granites and related rocks that were generated as the continents collided. The islands of the Shetland archipelago are also fringed by spectacular coastal features, nd such as rock arches, plunging cliffs and unspoilt beaches. The geology of Muckle Flugga and the ShetLAnd: A LA Holes of Scraada are amongst the delights geologists and tourists alike can enjoy. About the author Alan McKirdy has worked in conservation for over thirty years. He has played a variety of roles during that period; latterly as Head of Information Management at SNH. Alan has edited the Landscape nd Fashioned by Geology series since its inception and anticipates the completion of this 20 title series ScA shortly. -

Norse Naming Elements in Shetland and Faroe: a Comparative Study

NORSE NAMING ELEMENTS IN SHETLAND AND FAROE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY Lindsay J. Macgregor Studies of Norse place-names in the colonies have concentrated on the habitative elements stadir, b6lstadr, bjr and setr/sretr, and chronologies of settlement a'nd settlement expansion have been constructed from the distribution, of these elements (Marwick 1952, 227-251; Nicolaisen 1976, 85-94; Thuesen 1978, 113-117). These chronologies assume that elements replaced each other in popularity and that essentially they all had the same meaning of "farm". Marwick first er'eated a place-name hierarchy and chronology from the Norse habitative elements found in Orkney (1952, 227-251). According to his interpretation, byr was the earliest element, followed by stadir, b6lstadr, land, gardr, skall and setr. Nicolaisen expanded Marwick's theories to all the Norse colonies in the North Atlantic, constructing a chronological framework on the basis of the absence of certain elements from Iceland which he presumed to have been settled later than the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland (1976). Chronology was thus made the reason for the appearance and disappearance of place-name elements to the exclusion of all other factors such as regional differences or, perhaps most important of all, the function and· characteristics of the farms represented by the elements. More recently, however, Nicolaisen has noted that "More limited distribution is not always ... an indicator of an earlier linguistic stratum, just as less density in distribution is not always a sign of a late phase" (1984, 364). Faroe and Shetland provide excellent comparative material with which to analyse the significance of the distribution of habitative elements.