Cusuco National Park, Honduras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

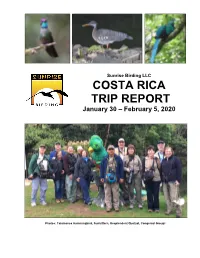

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Plantas Descritas Originalmente De Honduras Y Sus Nomenclaturas Equivalentes Actuales

Plantas descritas originalmente de Honduras y sus nomenclaturas equivalentes actuales Cyril H. Nelson Sutherland1 Resumen: Se hace una relación de 755 nombres de plantas descritas originalmente de Honduras y sus equivalencias nomenclaturales aceptadas actualmente. De éstas, 263 son endémicas de Honduras, entre las cuales Haptanthus hazlettii Goldberg & C. Nelson y Phrygilanthus nudus A. Molina R. se consideran extintas. Se propone Haptanthaceae como una familia nueva para acomodar a Haptanthus hazlettii. Asimismo se propone la combinación nueva Spermacoce fruticosa (Standl.) Govaerts var. pubescens (Standl. & L.O. Williams) C. Nelson. Palabras clave: Descripción, equivalencias, nomenclatura, taxonomía. Abstract: A relation is made of 755 names of plants originally described from Honduras, and their presently accepted nomenclatural equivalences. Of these, 263 are endemic to Honduras, among which, Haptanthus hazlettii Goldberg & C. Nelson and Phrygilanthus nudus A. Molina R. are considered extinct. Haptanthaceae is proposed as a new family in order to accommodate Haptanthus hazlettii. Also, the new combination Spermacoce fruticosa (Standl.) Govaerts var. pubescens (Standl. & L.O. Williams) C. Nelson is proposed. Key words: Description, equivalencies, nomenclature, taxonomy. Introducción Resultados y Discusión A pesar de que en Honduras no se ha hecho una Cereus schumannii Mathsson ex K. Schum. es una exploración planificada y exhaustiva de su flora, se han planta poco conocida y a la que, después de que Britton descrito del país más de 700 plantas, algunas de las y Rose la pasaran al género Lemaireocereus, nadie más cuales han resultado ser endémicas. Con la publicación se ha ocupado de ella, de manera que su verdadero status de Cassia mensarum (Leguminosae) en 1951, Antonio es incierto. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Download PCN Magnolia Multisite

Institution name plant NAMES for inventory::print name Accession # Provenanc Quantity Plant source The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore acuminata College 2005-355UN*A G 1 Unknown The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore acuminata College 2001-188UN*A U 1 Unknown The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore acuminata College 96-129*A G 1 Princeton Nurseries The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore acuminata College var. subcordata 99-203*B G 1 Longwood Gardens The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore acuminata College var. subcordata 93-206*A G 1 Woodlanders Nursery The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore acuminata College var. subcordata 'Brenda'2004-239*A G 1 Pat McCracken The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore 'Anilou' College 2008-202*A G 1 Pleasant Run Nursery The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore 'Anilou' College 2008-202*B G 1 Pleasant Run Nursery The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore 'Ann' College 68-165*A G 1 U. S. National Arboretum, Washington, DC The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore 'Banana College Split' 2004-237*A G 1 Pat McCracken The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore 'Betty' College 68-166*A G 1 U. S. National Arboretum, Washington, DC The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore 'Big Dude' College 2008-203*A G 1 Pleasant Run Nursery The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore ×brooklynensis College 'Black Beauty' 2008-204*A G 1 Pleasant Run Nursery The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore ×soulangeana College 'Jurmag1' 2010-069*A G 1 Pleasant Run Nursery The Scott Arboretum atMagnolia Swarthmore -

Lista Patron Mamiferos

NOMBRE EN ESPANOL NOMBRE CIENTIFICO NOMBRE EN INGLES ZARIGÜEYAS DIDELPHIDAE OPOSSUMS Zarigüeya Neotropical Didelphis marsupialis Common Opossum Zarigüeya Norteamericana Didelphis virginiana Virginia Opossum Zarigüeya Ocelada Philander opossum Gray Four-eyed Opossum Zarigüeya Acuática Chironectes minimus Water Opossum Zarigüeya Café Metachirus nudicaudatus Brown Four-eyed Opossum Zarigüeya Mexicana Marmosa mexicana Mexican Mouse Opossum Zarigüeya de la Mosquitia Micoureus alstoni Alston´s Mouse Opossum Zarigüeya Lanuda Caluromys derbianus Central American Woolly Opossum OSOS HORMIGUEROS MYRMECOPHAGIDAE ANTEATERS Hormiguero Gigante Myrmecophaga tridactyla Giant Anteater Tamandua Norteño Tamandua mexicana Northern Tamandua Hormiguero Sedoso Cyclopes didactylus Silky Anteater PEREZOSOS BRADYPODIDAE SLOTHS Perezoso Bigarfiado Choloepus hoffmanni Hoffmann’s Two-toed Sloth Perezoso Trigarfiado Bradypus variegatus Brown-throated Three-toed Sloth ARMADILLOS DASYPODIDAE ARMADILLOS Armadillo Centroamericano Cabassous centralis Northern Naked-tailed Armadillo Armadillo Común Dasypus novemcinctus Nine-banded Armadillo MUSARAÑAS SORICIDAE SHREWS Musaraña Americana Común Cryptotis parva Least Shrew MURCIELAGOS SAQUEROS EMBALLONURIDAE SAC-WINGED BATS Murciélago Narigudo Rhynchonycteris naso Proboscis Bat Bilistado Café Saccopteryx bilineata Greater White-lined Bat Bilistado Negruzco Saccopteryx leptura Lesser White-lined Bat Saquero Pelialborotado Centronycteris centralis Shaggy Bat Cariperro Mayor Peropteryx kappleri Greater Doglike Bat Cariperro Menor -

Bird Responses to Shade Coffee Production

Animal Conservation (2004) 7, 169–179 C 2004 The Zoological Society of London. Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S1367943004001258 Bird responses to shade coffee production Cesar´ Tejeda-Cruz and William J. Sutherland Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Conservation, School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK (Received 2 June 2003; accepted 16 October 2003) Abstract It has been documented that certain types of shade coffee plantations have both biodiversity levels similar to natural forest and high concentrations of wintering migratory bird species. These findings have triggered a campaign to promote shade coffee as a means of protecting Neotropical migratory birds. Bird censuses conducted in the El Triunfo Biosphere reserve in southern Mexico have confirmed that shade coffee plantations may have bird diversity levels similar to, or higher than, natural forest. However, coffee and forest differed in species composition. Species with a high sensitivity to disturbance were significantly more diverse and abundant in primary ecosystems. Neotropical migratory birds, granivorous and omnivorous species were more abundant in disturbed habitats. Insectivorous bird species were less abundant only in shaded monoculture. Foraging generalists and species that prefer the upper foraging stratum were more abundant in disturbed habitats, while a decline in low and middle strata foragers was found there. Findings suggests that shade coffee may be beneficial for generalist species (including several migratory species), but poor for forest specialists. Although shade coffee plantations may play an important role in maintaining local biodiversity, and as buffer areas for forest patches, promotion of shade coffee may lead to the transformation of forest into shade coffee, with the consequent loss of forest species. -

PAPILIONOIDEA Familia: NYMPHALIDAE Subfamilia: Nymphalinae Descripción. Mariposa

Marpesia corinna Latreille 1813 Superfamilia: PAPILIONOIDEA Familia: NYMPHALIDAE Subfamilia: Nymphalinae Descripción. Mariposa de tamaño grande, dorsalmente con una coloración oscura con una banda naranja, ancha, localizada entre el área postmedia y marginal del ala anterior. Ala posterior con una mancha fucsia que nace desde la base hasta el área postmedia. Presenta además dos proyecciones caudales, una de estas, de mayor tamaño localizada hacia el margen distal. Longitud del ala anterior: 29 - 32 mm. Aspectos ecológicos. Es bastante común en los períodos de sequía al borde de los caminos y al interior del bosque, también se le puede encontrar en áreas aledañas a corrientes de agua. Acostumbra posarse en pequeños charcos o sobre el suelo húmedo. Su vuelo es bastante rápido y rasante o al nivel del estrato herbáceo. Es muy activa durante las horas de mayor intensidad lumínica (Álvarez 1993). La planta nutricia de sus orugas es el Ficus sp. de la familia de las Moráceas. Distribución. En Colombia esta presente en la región andina entre 1800 y 2000 m (García – Robledo et al. 2002). En la cuenca del río Coello en la localidad Cay (1714 m). Marpesia coresia Godart 1823 Superfamilia: PAPILIONOIDEA Familia: NYMPHALIDAE Subfamilia: Nymphalinae Descripción. Alas con proyecciones caudales, patas anteriores muy reducidas y densamente cubiertas de vellosidades por lo que solo dos pares son ambulatorias. El tórax y el abdomen son anchos, la venación que presenta la celda discal es de tipo abierto en ambas alas. Ventralmente las alas exhiben una banda blanca que parte desde la base hasta la mitad del área media y de ahí en adelante una banda de color pardo hacia la margen distal. -

Phylogenetic Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Tribes and Genera in the Subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society 0024-4066The Linnean Society of London, 2005? 2005 862 227251 Original Article PHYLOGENY OF NYMPHALINAE N. WAHLBERG ET AL Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2005, 86, 227–251. With 5 figures . Phylogenetic relationships and historical biogeography of tribes and genera in the subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) NIKLAS WAHLBERG1*, ANDREW V. Z. BROWER2 and SÖREN NYLIN1 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331–2907, USA Received 10 January 2004; accepted for publication 12 November 2004 We infer for the first time the phylogenetic relationships of genera and tribes in the ecologically and evolutionarily well-studied subfamily Nymphalinae using DNA sequence data from three genes: 1450 bp of cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) (in the mitochondrial genome), 1077 bp of elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-a) and 400–403 bp of wing- less (both in the nuclear genome). We explore the influence of each gene region on the support given to each node of the most parsimonious tree derived from a combined analysis of all three genes using Partitioned Bremer Support. We also explore the influence of assuming equal weights for all characters in the combined analysis by investigating the stability of clades to different transition/transversion weighting schemes. We find many strongly supported and stable clades in the Nymphalinae. We are also able to identify ‘rogue’ -

Species List January 28 – February 6, 2020 | Compiled by Keith Hansen

Guatemala: Nature & Culture With Tikal Extension| Species List January 28 – February 6, 2020 | Compiled by Keith Hansen With Guides Keith Hansen, Patricia Briceño, Roland Rumm and local guide Freddie and participants Julie, Paul, Gwen, Gary, Barbara, Rolande, Brian, Jane, and Debbie. Itinerary Day 1: 1/29/20, Guatemala City. Clarion Hotel to Marroquin University and Textile Museum, to Guatemala Market, to Cocales “Crazy Gas Station” at intersection of CA 12 and 11 to Los Tarrales Natural Reserve. Day 2: 1/30/20, Los Tarrales Nat. Res. into jeeps and up to La Isla vista point. Down for lunch at lodge. Then San Pedro trail and back to La Rinconada lodge, for dinner. Day 3: 1/31/20, Pre-dawn, Volcan Fuego eruption. Los Tarrales, short walk on San Pedro Trail. Breakfast at lodge. Depart and drive to Fuentes Georginia Hot Springs Spa. Lunch with “mega flock”. Depart and drive to Xela (Quetzaltenango). Dinner at Hotel Bonifaz. Day 4: 2/1/20, Split group. One group, (Keith), up at 4:00 AM. Drive to Refugio del Quetzal for Quetzal, then viewing from mirador “overlook”. Then drive to San Rafael for lunch. Then drive back to Xela. Second group, (Patricia) Xela tour. Later some went back to “Owl” at Fuentes Georgino Hot Springs, then back to Xela. Day 5: 2/2/20, Xela breakfast at Hotel, depart for the market at Chichicastenango with stop at Continental Divide at 10,000 feet. To market, then lunch at “Mayan Inn”. Drive to Panajachel at Lago de Atitlan. Boarded a launch to cross the lake to Hotel Bambu, Santiago Atitlan. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Final Report for the University of Nottingham / Operation Wallacea Forest Projects, Honduras 2004

FINAL REPORT for the University of Nottingham / Operation Wallacea forest projects, Honduras 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS FINAL REPORT FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM / OPERATION WALLACEA FOREST PROJECTS, HONDURAS 2004 .....................................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................................................3 List of the projects undertaken in 2004, with scientists’ names .........................................................................4 Forest structure and composition ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bat diversity and abundance ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Bird diversity, abundance and ecology ............................................................................................................................ 4 Herpetofaunal diversity, abundance and ecology............................................................................................................. 4 Invertebrate diversity, abundance and ecology ................................................................................................................ 4 Primate behaviour........................................................................................................................................................... -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma