The Weather and Circulation of November 1954'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. Paris Agreements23 OCTOBER 1954I. Four Power Conference – Paris, 23 October 1954

THE ORGANISATION OF COLLECTIVE SELF-DEFENCE 35 5. Paris Agreements23 OCTOBER 1954I. Four Power Conference – Paris, 23 October 1954 The United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the French Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany agree as follows: 1. Protocol on the Termination of the Occupation Regime in the Federal Republic of Germany 2. Annexes I to V Attached to the Protocol on the Termination of the Occupation Regime in the Federal Republic of Germany 3. Letters Ten letters were exchanged following the signing of the agreements: letters from the Chancellor to the three Ministers for Foreign Affairs, letters from the three High Commissioners to the Chancellor and letters from the three Ministers for Foreign Affairs to the Chancellor. These letters deal with specific points in the Bonn Conventions which were deleted therefrom by mutual consent, the Parties concerned having agreed to deal with them by an exchange of letters. In the absence of the text of the Conventions their contents would be virtually unintelligible, so they have been omitted from the present work. 4. Convention on the Presence of Foreign Forces in the Federal Republic of Germany 5. Three-Power Declaration on Berlin II. Documents Signed by Five Parties 1. Declaration Inviting Italy and the Federal Republic of Germany to Accede to the Brussels Treaty – Paris, 23 October 1954 III. Nine-Power Conference 1. Protocol Modifying and Completing the Brussels Treaty – Paris, 23 October 1954 2. Protocol No. 11 on Forces of Western European Union – Paris, 23 October 1954 3. Protocol No. -

How Has Your State Pension Age Changed?

Increase in state pension age Pensions Act 2011 WOMEN Pensions Act 2011 Date of Birth Old pension date New pension date Delay on 1995 Act 06 April 1953 to 05 May 1953 06 May 2016 06 July 2016 2 months 06 May 1953 to 05 June 1953 06 July 2016 06 November 2016 4 months 06 June 1953 to 05 July 1953 06 September 2016 06 March 2017 6 months 06 July 1953 to 05 August 1953 06 November 2016 06 July 2017 8 months 06 August 1953 to 05 September 1953 06 January 2017 06 November 2017 10 months 06 September 1953 to 05 October 1953 06 March 2017 06 March 2018 1 year 06 October 1953 to 05 November 1953 06 May 2017 06 July 2018 1 yr 2 months 06 November 1953 to 05 December 1953 06 July 2017 06 November 2018 1 yr 4 months 06 December 1953 to 05 January 1954 06 September 2017 06 March 2019 1 yr 6 months 06 January 1954 to 05 February 1954 06 November 2017 06 May 2019 1yr 6 months 06 February 1954 to 05 March 1954 06 January 2018 06 July 2019 1yr 6 months 06 March 1954 to 05 April 1954 06 March 2018 06 September 2019 1yr 6 months 06 April 1954 to 05 May 1954 06 May 2018 06 November 2019 1yr 6 months 06 May 1954 to 05 June 1954 06 July 2018 08 January 2020 1yr 6 months 06 June 1954 to 05 July 1954 06 September 2018 06 March 2020 1yr 6 months 06 July 1954 to 05 August 1954 06 November 2018 06 May 2020 1yr 6 months 06 August 1954 to 05 September 1954 06 January 2019 06 July 2020 1yr 6 months 06 September 1954 to 05 October 1954 06 March 2019 06 September 2020 1yr 6 months 06 October 1954 to 05 November 1954 06 May 2019 66th birthday at least 1 yr 5 months 06 -

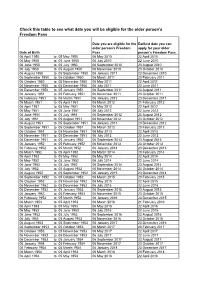

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Floods of October 1954 in the Chicago Area, Illinois and Indiana

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OP THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS OF OCTOBER 1954 IN THE CHICAGO AREA ILLINOIS AND INDIANA By Warren S. Daniels and Malcolm D. Hale Prepared in cooperation with the STATES OF ILLINOIS AND INDIANA Open-file report Washington, D. C., 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS OF OCTOBER 1954 IN THE CHICAGO AREA ILLINOIS AND INDIANA By Warren S. Daniels and Malcolm D. Hale Prepared in cooperation with the STATES OF ILLINOIS AND INDIANA Open-file report Washington, D. C., 1955 PREFACE This preliminary report on the floods of October 1954 in the Chicago area of Illinois and Indiana was prepared by the Water Resources Division, C. G. Paulsen, chief, under the general direction of J. V. B. Wells, chief, Surface Water Branch. Basic records of discharge in the area covered by this report were collected in cooperation with the Illinois De partment of Public Works and Buildings, Division of Waterways; the Indiana Flood Control and Water Resources Commission; and the Indiana Department of Conservation, Division of Water Re sources. The records of discharge were collected and computed under the direction of J. H. Morgan, district engineer, Champaign, 111.; and D. M. Corbett, district engineer, Indi anapolis, Ind. The data were computed and te^t prepared by the authors in the district offices in Illinois and Indiana. The report was assembled by the staff of the Technical Stand ards Section in Washington, D. C., Tate Dalrymple, chief. li CONTENTS Page Introduction............................................. 1 General description of floods............................ 1 Location.............................................. 1 Little Calumet River basin........................... -

October 1954

OCTOBER 1954 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS SURVEY OF CUHMENT BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FIELD SERVICE Albuquerque, N. Mex. No. 10 208 U. S, Courthouse UUA S. Broadway OCTOBER 1954 Atlanta 5. Ga, Memphis 3, Twin. 50 Seventh St. ML Boston 9, Mass. Miami 32, Fla. U. S. Post Office and 36 NE. First St, Courthouse Bldg. MfameapoHs2tMmn. Buffalo 3, N. Y. 607MarqoetteAre. 117 Ellicott Sti Charleston 4, S. C, Area 2, Sergeant Jasper Bldg. PAGE New York 17. N.Y. 110E.4Sth! THE BUSINESS SITUATION 1 Cheyenne, Wyo, 307 Federal Office Bldg. Philadelphia 7. Pa. National Income and Corporate Profits, Chicago 6, 111. 226 W, Jackson Blvd. Phomix.Ari,, Cincinnati 2, Ohio 137 N. Second Are. 422 U. S. Post Office and Courthouse 107 Sixth St, SPECIAL ARTICLES Cleveland 14, Ohio 1100 Chester Ave« 520 SW. Morrison St. Foreign Grants and Credits Dallas 2, Tea. U. S. Government, Fiscal 1954, 7 Reno,Ner. 1114 Commerce St. 1479 V«lh Are. Private and Public Debt in 1953, 13 Denver 2, Colo, Richmond 20, Va. 142 New Custom House WON.LomhardySt. Detroit 26, Mich, St. Louis 1, Mo. 230 W, Fort St. 1114 Market St, El Paso, Tex. Salt Lake Cit7l, Utah Chamber of Commerce 222 SW. Temple St. MONTHLY BUSINESS STATISTICS . S-l to S-40 Bid*. Houston 2, Tex. San Francisco U, Calif. Statistical Index . Inside back cover 430 Lamar Ave. 555 Battery St. Jacksonville 1, Fla, Sarannab. Ga. 311 W, Monroe St. 125-29 BullSt. Kansas City 6, Mo, Seattle 4, Wash. 911 Walnut St. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS October 1956 in Transportation, the Rise That Has Occurred in Payrolls Quently

OCTOBER 1956 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FIELD SERVICE No. 10 Albuquerque, N. Mex. Memphis 3, Term. 321 Post Office Bldg. 22 North Front St. OCTOBER 1956 Atlanta 23, Ga. Miami 32, Fla. 50 Seventh St. NE. 300 NE. First Ave. Boston 9, Mass. Minneapolis 2, Minn. U.S. Post Office and 2d Ave. South and Courthouse Bldg. 3d St. Buffalo 3, N. Y. New Orleans 12, La. 117 Ellicott St. 333 St. Charles Ave, Charleston 4, S. C. New York 17, N. Y. Area 2, 110 E. 45th St. PAGE Sergeant Jasper Bldg. THE BUSINESS SITUATION.. 1 Cheyenne, Wyo. Philadelphia 7, Pa. 307 Federal Office Bldg. 1015 Chestnut St. Recent Changes in Manufacturing and Trade. 2 National Income and Corporate Profits 7 Chicago 6, III. Phoenix, Ariz. 226 W. Jackson Blvd. 137 N. Second Ave. Cincinnati 2, Ohio Pittsburgh 22, Pa. * * * 442 U. S. Post Office 107 Sixth St. and Courthouse Portland 4, Oreg. SPECIAL ARTICLES Cleveland 14, Ohio 520 SW. Morrison St. 1100 Chester Ave. Financing Corporate Expansion in 1956 11 Dallas 2, Tex. Reno, Nev. Major Shift by Areas in Foreign Aid in Fiscal 1114 Commerce St. 1479 Wells Ave. 1956 17 Denver 2, Colo. Richmond 19, Va. 142 New Customhouse 1103 East Main St. * * * Detroit 26, Mich. St. Louis 1, Mo. 1114 Market St. MONTHLY BUSINESS STATISTICS S-l to S-40 438 Federal Bldg. Houston 2, Tex. Salt Lake City 1. Utah Statistical Index Inside back cover 430 Lamar Ave. 222 SW. Temple St. -

Communique, November 1954

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Communique, 1953-2020 Journalism 11-1954 Communique, November 1954 Montana State University (Missoula, Mont.). School of Journalism Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/communique Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Montana State University (Missoula, Mont.). School of Journalism, "Communique, November 1954" (1954). Communique, 1953-2020. 47. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/communique/47 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communique, 1953-2020 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHIVES Bue Is Acting J-School Dean; NY Times Reprints Scanlan Gets MSPA Post; Reinemer Article Dorothy Johnson Joins Staff “A Southern '...City Debates Prof. O. J. Bue has been ap In addition to the regular staff Nonsegregation,’’ a short article Secretary of Army Speaks pointed acting dean of the MSU members, Ray Wight and Ed Du by Vic Reinemer, appeared in School of Journalism, replacing gan, Miss Dorothy Johnson, secre the September 26 issue of the The election of Robert J. Scan of MSPA. Other officers included' Dr. James L. C. Ford. Dr. Ford tary of the State Press associa New York Times magazine sec lan, Miles City Daily Star, as R. E. Morrison, Missoulian-Sen- continues as a professor of journ tion, is teaching a magazine tion. president of Montana State Press tinel, second vice-president; Mel alism. -

NATO in the Beholder's Eye: Soviet Perceptions and Policies, 1949-1956

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Christian Ostermann, Lee H. Hamilton, NATO in the Beholder’s Eye: Director Director Soviet Perceptions and Policies, 1949-56 BOARD OF ADVISORY TRUSTEES: COMMITTEE: Vojtech Mastny Joseph A. Cari, Jr., William Taubman Chairman (Amherst College) Steven Alan Bennett, Working Paper No. 35 Chairman Vice Chairman PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss (Historian, Author) The Secretary of State Colin Powell; The Librarian of James H. Billington Congress (Librarian of Congress) James H. Billington; The Archivist of the United States Warren I. Cohen John W. Carlin; (University of Maryland- The Chairman of the Baltimore) National Endowment for the Humanities Bruce Cole; John Lewis Gaddis The Secretary of the (Yale University) Smithsonian Institution Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of James Hershberg Education (The George Washington Roderick R. Paige; University) The Secretary of Health & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Samuel F. Wells, Jr. (Woodrow Wilson PRIVATE MEMBERS Washington, D.C. Center) Carol Cartwright, John H. Foster, March 2002 Sharon Wolchik Jean L. Hennessey, (The George Washington Daniel L. Lamaute, University) Doris O. Mausui, Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

RESTRICTED 26 November 1955 WORKING PARTY 9 on UNITED

RESTRICTED 26 November 1955 WORKING PARTY 9 ON UNITED STATES WAIVER (AAA) Reference of Item ll(j) to the Working Party At their meeting on 25 November the CONTRACTING PARTIES, at-the request of the Netherlands delegation, referred to the Working Party Item ll(j) - United: States Dairy Products, report vmder Resolution of 5 November 1954» The following is the statement of the representative of the Netherlands: "Before entering into a substantive discussion on Item ll(j) - United States Dairy Products - we think it would be desirable to clear up beforehand the question of the relationship between this item and item 10(h) dealing with the waiver granted to the United States in connection with import restrictions imposed under. Section 22 of the United States Agricultural Adjustment Act. "Item '11(3 ) refers to the Resolution of the CONTRACTING PARTIES of 5 November 1954. It may be recalled that this Resolu tion was of a twofold character, although its two elements were .closely inter-related. As a matter of fact in November 1952 -;...;.the two elements were dealt with in two separate instruments: ... firstly, a Resolution dealing with the United States import restrictions on dairy products and, secondly, a determination authorizing the Netherlands Government to suspend certain of its , obligations under the General Agreement in view of these restrictions, ,jV "It seems to us that the first part of the 1954 Resolution -has in fact been overtaken as from 5 March 1955 by the waiver just mentioned and has thereby lost its practical significance. The waiver, however, declares explicitly that it does not preclude actions by contracting parties under Article XXIII, and the authorization granted to the Netherlands therefore in our opinion stands unaffected. -

Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 Ralph G. Morrissey (1903-1956) Papers, 1930 -1956 Processed by: Theodore Morrison, Jr. Accession Number: THS 721 Location: THS VI-E-5 Date: April 29, 1994 Microfilm Accession No.: 1453 The Ralph Morrissey Papers, 1930-1956, centers on Ralph Morrissey (1903- 1956) of Nashville, Tennessee, amateur photographer and newspaper literary review editor. The Ralph Morrissey Papers are a gift of Mrs. Eleanor Morrissey. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the Ralph Morrissey Papers may be made for scholarly research. Cubic feet of shelf space occupied: 4.58 cu. ft. Approximate number of items: ca. 300; 10 vols. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The Ralph Morrissey Papers contain 10 volumes and approximately 300 items spanning the period between 1930 and 1957. The collection is composed of accounts, an advertisement, clippings, correspondence, invitations, programs, lists, notes, a poem, photographs, press releases, publications, and school records. The bulk of the collection consists of clippings from The Nashville Tennessean featuring the literary review columns of Ralph Morrissey (1903-1956). Included within the correspondence are letters from notables such as Margaret Mitchell, Merrill Moore, Arna Bontemps, Anya Seton, and T.S. Stribling. An avid amateur photographer, Morrissey received numerous national awards. Included in the photographs section of the addition are several of his award- winning shots (see also the Ralph Morrissey Photograph Collection, ac. no. THS 484). Morrissey also garnered awards for his philatelic collection and became well-known as an aficionado of pipes and Sherlock Holmes mysteries. -

1954-1956 Adjutant General's Report

HEADQUARTERS MILITA.LtY DEPAR.TMENT STf,TE OF WASHIPG'TON Office of The Adju.tunt General Camp Murray, Fort Lewis, Washington December 10, 1956 The Honorable Arthur B. Langlie Governor of the State of Washington Executive Offices Olympia, Washington Dear Governor Langlie: .In conformity with the provisions of Title 38, Chap ter 38.12, Section 38.12.020, Revised Code of Washington, the biennial report of The Adjutant General of Washington is submitted herevv.i.th for the period November 1, 1954, to October 31, 1956, inclusive. The attached report is made up of individual reports prepared by each section of The Adjutant General's Office and the u. s. Property and Fiscal Officer and presents a comprehensive coverage of the operations and condition of the N:Llitary Department and· the Washington National Guard during the reporting period. Respectfully submitted, J ., I} C ,. , • I ~t.:;Cv.._l....JvJ.:> /,r)_.. )...j\..AA.J._/-../V• v rt I LIIBURN H. STEVENS 1'1ajor General, Wash NG The Adjutant General T-A-B-L-E 0-F C-0-N-T-E-N-T-S PAGES FORETNORD • • . • . " . 1 FULL-TIME PERSONNEL. " 1-2 FEDEHAL ADVISORS •• . 2 REPORT OF OPERATIONS & TRAINING SECTION . • • • • 3 Organizational Changes ••••• . " . 3-4 Sun-uner Field 'rraining • • • • • • 4 Federal Inspections • • , . ,• . 5 Resident Instruction. • • , . 6~8 Army Extension Courses •. • • • 8 AAA On-Site PrograJn • • • • • . 9 National Rifle Matches , • . 10 Security Clearance Program. • • • • • • • • 10 Publications Stockroom. • • • • • • 10 REPORT OF MILITARY PERSONNEL SECTIOii . • • . • • 11 Overall Strength Analysis • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 11-13 Officers and Warrant Officers • , • • • • • . • • 14-15 Officer Inactive NG • • • , • • . • • • • 15 Changes in Status of Officers • • • , • , • • . -

Floods of October 1954 in the Chicago Area Illinois and Indiana

Floods of October 1954 in the Chicago Area Illinois and Indiana By WARREN S. DANIELS and MALCOLM D. HALE FLOODS OF 1954 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1370-B Prepared in cooperation with the States of Illinois and Indiana UNITED STATES GOVE'RNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1958 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price 35 cents PREFACE This report on the floods of October 1954 in the Chicago area, Illinois and Indiana, was prepared by the U. S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division, C. G. Paulsen, chief, under the general direction of J. V. B. Wells, chief, Surface Water Branch. Basic records of stage and discharge were collected in cooper ation with the following agencies: Illinois Department of Public Works and Buildings, Division of Waterways; Illinois Department of Registration and Education, Water Survey Division; Department of Highways, Cook County, Ill. Indiana Flood Control and Water Resources Commission; and Indiana Department of Conservation, Division of Water Resources. The flood profile data were furnished by the Illinois Division of Waterways and by the Corps of Engineers. The records of stage and discharge were collected and computed under the direction of J. H. Morgan, district engineer. Champaign, Ill .• and D. M. Corbett. district engineer. Indianapolis. Ind. The Illinois part of the report was prepared by W. S. Daniels. the Indiana part by M.D. Hale. each being assisted by personnel in his respective district. The short section on flood frequency was pre pared by the special studies unit of the Champaign district.