Mucosal Effects of Tenofovir 1%

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methods for Identifying Circadian Rhythm

(19) *EP003302716B1* (11) EP 3 302 716 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61Q 17/04 (2006.01) G01N 33/50 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) 14.10.2020 Bulletin 2020/42 A61Q 19/08 A61Q 19/00 C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) (21) Application number: 16729482.6 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 08.06.2016 PCT/US2016/036401 (87) International publication number: WO 2016/200905 (15.12.2016 Gazette 2016/50) (54) METHODS FOR IDENTIFYING CIRCADIAN RHYTHM-DEPENDENT COSMETIC AGENTS FOR SKIN CARE COMPOSITIONS VERFAHREN ZUR IDENTIFIZIERUNG VON BIORHYTHMUSABHÄNGIGEN KOSMETISCHEN MITTELN FÜR HAUTPFLEGEZUSAMMENSETZUNGEN PROCÉDÉS D’IDENTIFICATION D’AGENTS COSMÉTIQUES DÉPENDANT DU RYTHME CIRCADIEN POUR DES COMPOSITIONS DE SOIN DE LA PEAU (84) Designated Contracting States: • OSBORNE, Rosemarie AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 (US) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR (74) Representative: P&G Patent Belgium UK N.V. Procter & Gamble Services Company S.A. (30) Priority: 08.06.2015 US 201562172498 P Temselaan 100 1853 Strombeek-Bever (BE) (43) Date of publication of application: 11.04.2018 Bulletin 2018/15 (56) References cited: WO-A1-2010/079285 JP-A- 2010 098 965 (73) Proprietor: The Procter & Gamble Company US-A1- 2009 220 481 US-A1- 2010 028 317 Cincinnati, OH 45202 (US) US-A1- 2015 071 895 (72) Inventors: • GEYFMAN MIKHAIL ET AL: "Clock genes, hair • MULLINS, Lisa, Ann growth and aging", AGING, NEW YORK, NY, US, Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 (US) vol. -

KIAA0101/P15paf) Over Expression and Gene Copy Number Alterations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tissues

PCNA-associated Factor (KIAA0101/p15PAF) over expression and Gene Copy Number Alterations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tissues Anchalee Tantiwetrueangdet Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Ravat Panvichian ( [email protected] ) Mahidol University Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5282-8166 Pattana Sornmayura Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Surasak Leelaudomlipi Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Research article Keywords: PCNA-associated factor (KIAA0101/p15PAF), droplet digital PCR, real-time PCR, p53 tumor suppressor protein, Ki-67 proliferation marker protein, HCC DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-39782/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/18 Abstract Background PCNA-associated factor (KIAA0101/p15PAF) is a cell-cycle regulated oncoprotein that regulates DNA synthesis, maintenance of DNA methylation, and DNA-damage bypass, through the interaction with the human sliding clamp PCNA. KIAA0101 is overexpressed in various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, it remains unknown whether KIAA0101 gene ampliƒcation occurs and causally correlates with the KIAA0101 overexpression in HCC. This question is relevant to the development of the optimal test(s) for KIAA0101 and the strategies to target KIAA0101 in HCC. Methods In this study, we validated KIAA0101 mRNA expression levels by quantitative real-time PCR in 40 pairs of snap-frozen HCC and matched-non-cancerous tissues; we then evaluated KIAA0101 gene copy numbers by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) in 36 pairs of the tissues. Besides, KIAA0101 protein expression was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in 81 pairs of formalin-ƒxed para∆n-embedded (FFPE) tissues. -

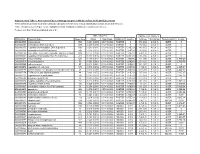

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Supplementary Material

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Page 1 / 45 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Appendix A1: Neuropsychological protocol. Appendix A2: Description of the four cases at the transitional stage. Table A1: Clinical status and center proportion in each batch. Table A2: Complete output from EdgeR. Table A3: List of the putative target genes. Table A4: Complete output from DIANA-miRPath v.3. Table A5: Comparison of studies investigating miRNAs from brain samples. Figure A1: Stratified nested cross-validation. Figure A2: Expression heatmap of miRNA signature. Figure A3: Bootstrapped ROC AUC scores. Figure A4: ROC AUC scores with 100 different fold splits. Figure A5: Presymptomatic subjects probability scores. Figure A6: Heatmap of the level of enrichment in KEGG pathways. Kmetzsch V, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2021; 92:485–493. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324647 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Appendix A1. Neuropsychological protocol The PREV-DEMALS cognitive evaluation included standardized neuropsychological tests to investigate all cognitive domains, and in particular frontal lobe functions. The scores were provided previously (Bertrand et al., 2018). Briefly, global cognitive efficiency was evaluated by means of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (MDRS). Frontal executive functions were assessed with Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), forward and backward digit spans, Trail Making Test part A and B (TMT-A and TMT-B), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), and Symbol-Digit Modalities test. -

Supplementary Data

Supplemental Data Microarray data analysis. In order to identify differentially expressed genes, we compared the melanoma samples to the benign nevi and the normal skin samples separately. The first analysis consisted of the 45 melanoma and 7 normal skin samples; the second analysis consisted of 45 melanoma and 18 nevi samples (Fig. S1). Significance analysis of microarray (SAM) was performed (17). Parameters for SAM were set as ∆=2.5 and fold change = 2.0 with 1,000 permutations. FDR was 1%. There was no missing data and the default random number was used. Next, percentile analysis was conducted. For up-regulated genes, the 30%ile in melanoma samples was compared to the maximum of the normal samples, or that of nevi samples. Student T-test with Bonferroni correction was also performed with cut-off p<0.05 in order to ensure that the selected genes had significant differential expression between the two groups of the samples. As a final step, we identified common genes between the melanoma/benign and melanoma /normal gene lists and reported a single list of genes up-regulated in melanoma (Table S1). 1 Fig. S1. 22,283 genes on Affymetrix U33a chip 15,795 genes with 2 or more “Present” calls Melanoma vs. Skin Melanoma vs. Benign nevi SAM FDR < 1%, fold-change > 2 2,326 up-regulated genes in cancer 828 up-regulated genes in cancer Percentile analysis Up-regulated in > 30% of melanoma 1,941 genes 527 genes T test with Bonferroni correction P < 0.05 592 genes (439 common genes) 492 genes 2 Table S1. -

PCNA-Associated Factor (KIAA0101/PCLAF) Overexpression and Gene Copy Number Alterations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tissues

PCNA-associated factor (KIAA0101/PCLAF) overexpression and gene copy number alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues Anchalee Tantiwetrueangdet Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Ravat Panvichian ( [email protected] ) Mahidol University Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5282-8166 Pattana Sornmayura Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Surasak Leelaudomlipi Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital Jill A. Macoska Georgia Southern University College of Science and Mathematics Research article Keywords: PCNA-associated factor (KIAA0101/PCLAF), droplet digital PCR, real-time PCR, p53 tumor suppressor protein, Ki-67 proliferation marker protein, HCC Posted Date: December 16th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-39782/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on March 20th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-07994-3. Page 1/21 Abstract Background: PCNA-associated factor, the protein encoded by the KIAA0101/PCLAF gene, is a cell-cycle regulated oncoprotein that regulates DNA synthesis, maintenance of DNA methylation, and DNA-damage bypass, through the interaction with the human sliding clamp PCNA. KIAA0101/PCLAF is overexpressed in various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, it remains unknown whether KIAA0101/PCLAF overexpression is coupled to gene amplication in HCC. Methods: KIAA0101/PCLAF mRNA expression levels were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR in 40 pairs of snap-frozen HCC and matched-non-cancerous tissues,KIAA0101/PCLAF gene copy numbers were evaluated by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) in 36 pairs of the tissues, and protein expression was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in 81 pairs of formalin-xed paran-embedded (FFPE) tissues. -

Supplemental Table S1. Primers for Sybrgreen Quantitative RT-PCR Assays

Supplemental Table S1. Primers for SYBRGreen quantitative RT-PCR assays. Gene Accession Primer Sequence Length Start Stop Tm GC% GAPDH NM_002046.3 GAPDH F TCCTGTTCGACAGTCAGCCGCA 22 39 60 60.43 59.09 GAPDH R GCGCCCAATACGACCAAATCCGT 23 150 128 60.12 56.52 Exon junction 131/132 (reverse primer) on template NM_002046.3 DNAH6 NM_001370.1 DNAH6 F GGGCCTGGTGCTGCTTTGATGA 22 4690 4711 59.66 59.09% DNAH6 R TAGAGAGCTTTGCCGCTTTGGCG 23 4797 4775 60.06 56.52% Exon junction 4790/4791 (reverse primer) on template NM_001370.1 DNAH7 NM_018897.2 DNAH7 F TGCTGCATGAGCGGGCGATTA 21 9973 9993 59.25 57.14% DNAH7 R AGGAAGCCATGTACAAAGGTTGGCA 25 10073 10049 58.85 48.00% Exon junction 9989/9990 (forward primer) on template NM_018897.2 DNAI1 NM_012144.2 DNAI1 F AACAGATGTGCCTGCAGCTGGG 22 673 694 59.67 59.09 DNAI1 R TCTCGATCCCGGACAGGGTTGT 22 822 801 59.07 59.09 Exon junction 814/815 (reverse primer) on template NM_012144.2 RPGRIP1L NM_015272.2 RPGRIP1L F TCCCAAGGTTTCACAAGAAGGCAGT 25 3118 3142 58.5 48.00% RPGRIP1L R TGCCAAGCTTTGTTCTGCAAGCTGA 25 3238 3214 60.06 48.00% Exon junction 3124/3125 (forward primer) on template NM_015272.2 Supplemental Table S2. Transcripts that differentiate IPF/UIP from controls at 5%FDR Fold- p-value Change Transcript Gene p-value p-value p-value (IPF/UIP (IPF/UIP Cluster ID RefSeq Symbol gene_assignment (Age) (Gender) (Smoking) vs. C) vs. C) NM_001178008 // CBS // cystathionine-beta- 8070632 NM_001178008 CBS synthase // 21q22.3 // 875 /// NM_0000 0.456642 0.314761 0.418564 4.83E-36 -2.23 NM_003013 // SFRP2 // secreted frizzled- 8103254 NM_003013 -

1 Mucosal Effects of Tenofovir 1% Gel 1 Florian Hladik1,2,5*, Adam

1 Mucosal effects of tenofovir 1% gel 2 Florian Hladik1,2,5*, Adam Burgener8,9, Lamar Ballweber5, Raphael Gottardo4,5,6, Lucia Vojtech1, 3 Slim Fourati7, James Y. Dai4,6, Mark J. Cameron7, Johanna Strobl5, Sean M. Hughes1, Craig 4 Hoesley10, Philip Andrew12, Sherri Johnson12, Jeanna Piper13, David R. Friend14, T. Blake Ball8,9, 5 Ross D. Cranston11,16, Kenneth H. Mayer15, M. Juliana McElrath2,3,5 & Ian McGowan11,16 6 Departments of 1Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2Medicine, 3Global Health, 4Biostatistics, University 7 of Washington, Seattle, USA; 5Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, 6Public Health Sciences 8 Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, USA; 7Vaccine and Gene Therapy 9 Institute-Florida, Port St. Lucie, USA; 8Department of Medical Microbiology, University of 10 Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada; 9National HIV and Retrovirology Laboratories, Public Health 11 Agency of Canada; 10University of Alabama, Birmingham, USA; 11University of Pittsburgh 12 School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, USA; 12FHI 360, Durham, USA; 13Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, 13 Bethesda, USA; 14CONRAD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Arlington, USA; 15Fenway Health, 14 Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA; 16Microbicide Trials 15 Network, Magee-Women’s Research Institute, Pittsburgh, USA. 16 Adam Burgener and Lamar Ballweber contributed equally to this work. 17 *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] 18 Address reprint requests to Florian Hladik at [email protected] or Ian McGowan at 19 [email protected]. 20 Abstract: 150 words. Main text (without Methods): 2,603 words. Methods: 3,953 words 1 21 ABSTRACT 22 Tenofovir gel is being evaluated for vaginal and rectal pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV 23 transmission. -

Program in Human Neutrophils Fails To

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology Anaplasma phagocytophilum , 20 of which you can access for free at: 2005; 174:6364-6372; ; from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication J Immunol doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6364 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/174/10/6364 Insights into Pathogen Immune Evasion Mechanisms: Fails to Induce an Apoptosis Differentiation Program in Human Neutrophils Dori L. Borjesson, Scott D. Kobayashi, Adeline R. Whitney, Jovanka M. Voyich, Cynthia M. Argue and Frank R. DeLeo cites 28 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2005/05/03/174.10.6364.DC1 This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/174/10/6364.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* • Why • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2005 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 25, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Insights into Pathogen Immune Evasion Mechanisms: Anaplasma phagocytophilum Fails to Induce an Apoptosis Differentiation Program in Human Neutrophils1 Dori L. -

KIAA0101 and Ubch10 Interact to Regulate Non- Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Proliferation by Disrupting the Function of the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint

KIAA0101 and UbcH10 interact to regulate non- small cell lung cancer cell proliferation by disrupting the function of the spindle assembly checkpoint Han Lei Shanghai East Hospital Kun Wang Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Tongying Jiang Shanghai East Hospital Jingjing Lu Shanghai East Hospital Xue Dong Shanghai East Hospital Feilong Wang Shanghai East Hospital Qiang Li Shanghai East Hospital Liming Zhao ( [email protected] ) Shanghai East Hospital Research article Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, spindle assembly checkpoint, UbcH10, KIAA0101 Posted Date: March 3rd, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-15900/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on October 2nd, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07463-3. Page 1/22 Abstract Background Chromosome mis-segregation caused by spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) dysfunction during mitosis is an important pathogenic factor in cancer, and modulating SAC function has emerged as a potential novel therapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). UbcH10 is considered to be associated with SAC function and the pathological types and clinical grades of NSCLC. KIAA0101, which contains a highly conserved proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-binding motif that is involved in DNA repair in cancer cells, plays an important role in the regulation of SAC function in NSCLC cells, and bioinformatics predictions showed that this regulatory role is related to UbcH10. We hypothesized KIAA0101 and UbcH10 interact to mediate SAC dysfunction and neoplastic transformation during the development of USCLC. -

Distribution of Applied AC EF Strength in a 6−Well Plate During Htcepi Cell Stimulation

Supplementary information Supplementary Figure S1: Distribution of applied AC EF strength in a 6−well plate during hTCEpi cell stimulation. (electric potential: 200 mV; frequency: 20 Hz; wave form). Simulated by finite element method and the color−coding of the scale bar defines the range of values. Supplementary Figure S2: Analysis of the gene and protein array data. (A) represents principal component analysis of the RMA normalized microarray data. (B) represents hierarchical clustering of the protein extracts based on differentially expressed proteins. Supplementary Figure S3: Analysis of the gene array data. (A) represents the clustering heat map of the calibrated samples. (B) represents Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes. X−axis shows the measured fold changes in the expression whereas the y−axis shows the significance of the change in terms of negative log (base 10) of the p−value. The threshold used to select the differentially expressed genes is 2 for expression change and 0.05 for significance. Supplementary Table S1 Gene array data: upregulated during AC EF stimulation downregulated during AC EF stimulation Gene Symbol Fold Change Gene Symbol Fold Change MMP1 48.87 SAMM50 −2 STC1 47.51 PGAP1 −2 PAPL 45.43 PRODH −2 HBEGF 34.58 CEP97 −2 IL1B 33.7 EML1 −2 TM4SF19 27.27 IRX2 −2 TRIB3 22.69 FETUB −2.01 MMP10 20.93 METAP1D −2.01 TM4SF19−TCTEX1D2 20.69 ZMYM3 −2.01 PTGS2 20.3 TGFBR3 −2.01 SLC2A3 19.33 ZMAT3 −2.01 IL1RL1 19.2 FAM111A −2.01 RAC2 14.32 LRRC1 −2.01 PLAUR 13.05 OR5P3 −2.01 BMP6 12.01 EFNA5 −2.01 ID1 11.59 NCAPG