Chapter 4 Cache Memory Computer Organization and Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory Hierarchy Memory Hierarchy

Memory Key challenge in modern computer architecture Lecture 2: different memory no point in blindingly fast computation if data can’t be and variable types moved in and out fast enough need lots of memory for big applications Prof. Mike Giles very fast memory is also very expensive [email protected] end up being pushed towards a hierarchical design Oxford University Mathematical Institute Oxford e-Research Centre Lecture 2 – p. 1 Lecture 2 – p. 2 CPU Memory Hierarchy Memory Hierarchy Execution speed relies on exploiting data locality 2 – 8 GB Main memory 1GHz DDR3 temporal locality: a data item just accessed is likely to be used again in the near future, so keep it in the cache ? 200+ cycle access, 20-30GB/s spatial locality: neighbouring data is also likely to be 6 used soon, so load them into the cache at the same 2–6MB time using a ‘wide’ bus (like a multi-lane motorway) L3 Cache 2GHz SRAM ??25-35 cycle access 66 This wide bus is only way to get high bandwidth to slow 32KB + 256KB main memory ? L1/L2 Cache faster 3GHz SRAM more expensive ??? 6665-12 cycle access smaller registers Lecture 2 – p. 3 Lecture 2 – p. 4 Caches Importance of Locality The cache line is the basic unit of data transfer; Typical workstation: typical size is 64 bytes 8 8-byte items. ≡ × 10 Gflops CPU 20 GB/s memory L2 cache bandwidth With a single cache, when the CPU loads data into a ←→ 64 bytes/line register: it looks for line in cache 20GB/s 300M line/s 2.4G double/s ≡ ≡ if there (hit), it gets data At worst, each flop requires 2 inputs and has 1 output, if not (miss), it gets entire line from main memory, forcing loading of 3 lines = 100 Mflops displacing an existing line in cache (usually least ⇒ recently used) If all 8 variables/line are used, then this increases to 800 Mflops. -

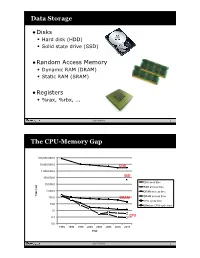

Data Storage the CPU-Memory

Data Storage •Disks • Hard disk (HDD) • Solid state drive (SSD) •Random Access Memory • Dynamic RAM (DRAM) • Static RAM (SRAM) •Registers • %rax, %rbx, ... Sean Barker 1 The CPU-Memory Gap 100,000,000.0 10,000,000.0 Disk 1,000,000.0 100,000.0 SSD Disk seek time 10,000.0 SSD access time 1,000.0 DRAM access time Time (ns) Time 100.0 DRAM SRAM access time CPU cycle time 10.0 Effective CPU cycle time 1.0 0.1 CPU 0.0 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003 2005 2010 2015 Year Sean Barker 2 Caching Smaller, faster, more expensive Cache 8 4 9 10 14 3 memory caches a subset of the blocks Data is copied in block-sized 10 4 transfer units Larger, slower, cheaper memory Memory 0 1 2 3 viewed as par@@oned into “blocks” 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 3 Cache Hit Request: 14 Cache 8 9 14 3 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 4 Cache Miss Request: 12 Cache 8 12 9 14 3 12 Request: 12 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 5 Locality ¢ Temporal locality: ¢ Spa0al locality: Sean Barker 6 Locality Example (1) sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < n; i++) sum += a[i]; return sum; Sean Barker 7 Locality Example (2) int sum_array_rows(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < M; i++) for (j = 0; j < N; j++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 8 Locality Example (3) int sum_array_cols(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (j = 0; j < N; j++) for (i = 0; i < M; i++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 9 The Memory Hierarchy The Memory Hierarchy Smaller On 1 cycle to access CPU Chip Registers Faster Storage Costlier instrs can L1, L2 per byte directly Cache(s) ~10’s of cycles to access access (SRAM) Main memory ~100 cycles to access (DRAM) Larger Slower Flash SSD / Local network ~100 M cycles to access Cheaper Local secondary storage (disk) per byte slower Remote secondary storage than local (tapes, Web servers / Internet) disk to access Sean Barker 10. -

Virtual Memory

Chapter 4 Virtual Memory Linux processes execute in a virtual environment that makes it appear as if each process had the entire address space of the CPU available to itself. This virtual address space extends from address 0 all the way to the maximum address. On a 32-bit platform, such as IA-32, the maximum address is 232 − 1or0xffffffff. On a 64-bit platform, such as IA-64, this is 264 − 1or0xffffffffffffffff. While it is obviously convenient for a process to be able to access such a huge ad- dress space, there are really three distinct, but equally important, reasons for using virtual memory. 1. Resource virtualization. On a system with virtual memory, a process does not have to concern itself with the details of how much physical memory is available or which physical memory locations are already in use by some other process. In other words, virtual memory takes a limited physical resource (physical memory) and turns it into an infinite, or at least an abundant, resource (virtual memory). 2. Information isolation. Because each process runs in its own address space, it is not possible for one process to read data that belongs to another process. This improves security because it reduces the risk of one process being able to spy on another pro- cess and, e.g., steal a password. 3. Fault isolation. Processes with their own virtual address spaces cannot overwrite each other’s memory. This greatly reduces the risk of a failure in one process trig- gering a failure in another process. That is, when a process crashes, the problem is generally limited to that process alone and does not cause the entire machine to go down. -

Make the Most out of Last Level Cache in Intel Processors In: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Eurosys Conference (Eurosys'19), Dresden, Germany, 25-28 March 2019

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper presented at EuroSys'19. Citation for the original published paper: Farshin, A., Roozbeh, A., Maguire Jr., G Q., Kostic, D. (2019) Make the Most out of Last Level Cache in Intel Processors In: Proceedings of the Fourteenth EuroSys Conference (EuroSys'19), Dresden, Germany, 25-28 March 2019. ACM Digital Library N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-244750 Make the Most out of Last Level Cache in Intel Processors Alireza Farshin∗† Amir Roozbeh∗ KTH Royal Institute of Technology KTH Royal Institute of Technology [email protected] Ericsson Research [email protected] Gerald Q. Maguire Jr. Dejan Kostić KTH Royal Institute of Technology KTH Royal Institute of Technology [email protected] [email protected] Abstract between Central Processing Unit (CPU) and Direct Random In modern (Intel) processors, Last Level Cache (LLC) is Access Memory (DRAM) speeds has been increasing. One divided into multiple slices and an undocumented hashing means to mitigate this problem is better utilization of cache algorithm (aka Complex Addressing) maps different parts memory (a faster, but smaller memory closer to the CPU) in of memory address space among these slices to increase order to reduce the number of DRAM accesses. the effective memory bandwidth. After a careful study This cache memory becomes even more valuable due to of Intel’s Complex Addressing, we introduce a slice- the explosion of data and the advent of hundred gigabit per aware memory management scheme, wherein frequently second networks (100/200/400 Gbps) [9]. -

Migration from IBM 750FX to MPC7447A by Douglas Hamilton European Applications Engineering Networking and Computing Systems Group Freescale Semiconductor, Inc

Freescale Semiconductor AN2808 Application Note Rev. 1, 06/2005 Migration from IBM 750FX to MPC7447A by Douglas Hamilton European Applications Engineering Networking and Computing Systems Group Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. Contents 1 Scope and Definitions 1. Scope and Definitions . 1 2. Feature Overview . 2 The purpose of this application note is to facilitate migration 3. 7447A Specific Features . 12 from IBM’s 750FX-based systems to Freescale’s 4. Programming Model . 16 MPC7447A. It addresses the differences between the 5. Hardware Considerations . 27 systems, explaining which features have changed and why, 6. Revision History . 30 before discussing the impact on migration in terms of hardware and software. Throughout this document the following references are used: • 750FX—which applies to Freescale’s MPC750, MPC740, MPC755, and MPC745 devices, as well as to IBM’s 750FX devices. Any features specific to IBM’s 750FX will be explicitly stated as such. • MPC7447A—which applies to Freescale’s MPC7450 family of products (MPC7450, MPC7451, MPC7441, MPC7455, MPC7445, MPC7457, MPC7447, and MPC7447A) except where otherwise stated. Because this document is to aid the migration from 750FX, which does not support L3 cache, the L3 cache features of the MPC745x devices are not mentioned. © Freescale Semiconductor, Inc., 2005. All rights reserved. Feature Overview 2 Feature Overview There are many differences between the 750FX and the MPC7447A devices, beyond the clear differences of the core complex. This section covers the differences between the cores and then other areas of interest including the cache configuration and system interfaces. 2.1 Cores The key processing elements of the G3 core complex used in the 750FX are shown below in Figure 1, and the G4 complex used in the 7447A is shown in Figure 2. -

Caches & Memory

Caches & Memory Hakim Weatherspoon CS 3410 Computer Science Cornell University [Weatherspoon, Bala, Bracy, McKee, and Sirer] Programs 101 C Code RISC-V Assembly int main (int argc, char* argv[ ]) { main: addi sp,sp,-48 int i; sw x1,44(sp) int m = n; sw fp,40(sp) int sum = 0; move fp,sp sw x10,-36(fp) for (i = 1; i <= m; i++) { sw x11,-40(fp) sum += i; la x15,n } lw x15,0(x15) printf (“...”, n, sum); sw x15,-28(fp) } sw x0,-24(fp) li x15,1 sw x15,-20(fp) Load/Store Architectures: L2: lw x14,-20(fp) lw x15,-28(fp) • Read data from memory blt x15,x14,L3 (put in registers) . • Manipulate it .Instructions that read from • Store it back to memory or write to memory… 2 Programs 101 C Code RISC-V Assembly int main (int argc, char* argv[ ]) { main: addi sp,sp,-48 int i; sw ra,44(sp) int m = n; sw fp,40(sp) int sum = 0; move fp,sp sw a0,-36(fp) for (i = 1; i <= m; i++) { sw a1,-40(fp) sum += i; la a5,n } lw a5,0(x15) printf (“...”, n, sum); sw a5,-28(fp) } sw x0,-24(fp) li a5,1 sw a5,-20(fp) Load/Store Architectures: L2: lw a4,-20(fp) lw a5,-28(fp) • Read data from memory blt a5,a4,L3 (put in registers) . • Manipulate it .Instructions that read from • Store it back to memory or write to memory… 3 1 Cycle Per Stage: the Biggest Lie (So Far) Code Stored in Memory (also, data and stack) compute jump/branch targets A memory register ALU D D file B +4 addr PC B control din dout M inst memory extend new imm forward pc Stack, Data, Code detect unit hazard Stored in Memory Instruction Instruction Write- ctrl ctrl ctrl Fetch Decode Execute Memory Back IF/ID -

Embedded DRAM

Embedded DRAM Raviprasad Kuloor Semiconductor Research and Development Centre, Bangalore IBM Systems and Technology Group DRAM Topics Introduction to memory DRAM basics and bitcell array eDRAM operational details (case study) Noise concerns Wordline driver (WLDRV) and level translators (LT) Challenges in eDRAM Understanding Timing diagram – An example References Slide 1 Acknowledgement • John Barth, IBM SRDC for most of the slides content • Madabusi Govindarajan • Subramanian S. Iyer • Many Others Slide 2 Topics Introduction to memory DRAM basics and bitcell array eDRAM operational details (case study) Noise concerns Wordline driver (WLDRV) and level translators (LT) Challenges in eDRAM Understanding Timing diagram – An example Slide 3 Memory Classification revisited Slide 4 Motivation for a memory hierarchy – infinite memory Memory store Processor Infinitely fast Infinitely large Cycles per Instruction Number of processor clock cycles (CPI) = required per instruction CPI[ ∞ cache] Finite memory speed Memory store Processor Finite speed Infinite size CPI = CPI[∞ cache] + FCP Finite cache penalty Locality of reference – spatial and temporal Temporal If you access something now you’ll need it again soon e.g: Loops Spatial If you accessed something you’ll also need its neighbor e.g: Arrays Exploit this to divide memory into hierarchy Hit L2 L1 (Slow) Processor Miss (Fast) Hit Register Cache size impacts cycles-per-instruction Access rate reduces Slower memory is sufficient Cache size impacts cycles-per-instruction For a 5GHz -

Cache-Aware Roofline Model: Upgrading the Loft

1 Cache-aware Roofline model: Upgrading the loft Aleksandar Ilic, Frederico Pratas, and Leonel Sousa INESC-ID/IST, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal ilic,fcpp,las @inesc-id.pt f g Abstract—The Roofline model graphically represents the attainable upper bound performance of a computer architecture. This paper analyzes the original Roofline model and proposes a novel approach to provide a more insightful performance modeling of modern architectures by introducing cache-awareness, thus significantly improving the guidelines for application optimization. The proposed model was experimentally verified for different architectures by taking advantage of built-in hardware counters with a curve fitness above 90%. Index Terms—Multicore computer architectures, Performance modeling, Application optimization F 1 INTRODUCTION in Tab. 1. The horizontal part of the Roofline model cor- Driven by the increasing complexity of modern applica- responds to the compute bound region where the Fp can tions, microprocessors provide a huge diversity of compu- be achieved. The slanted part of the model represents the tational characteristics and capabilities. While this diversity memory bound region where the performance is limited is important to fulfill the existing computational needs, it by BD. The ridge point, where the two lines meet, marks imposes challenges to fully exploit architectures’ potential. the minimum I required to achieve Fp. In general, the A model that provides insights into the system performance original Roofline modeling concept [10] ties the Fp and the capabilities is a valuable tool to assist in the development theoretical bandwidth of a single memory level, with the I and optimization of applications and future architectures. -

Virtual Memory - Paging

Virtual memory - Paging Johan Montelius KTH 2020 1 / 32 The process code heap (.text) data stack kernel 0x00000000 0xC0000000 0xffffffff Memory layout for a 32-bit Linux process 2 / 32 Segments - a could be solution Processes in virtual space Address translation by MMU (base and bounds) Physical memory 3 / 32 one problem Physical memory External fragmentation: free areas of free space that is hard to utilize. Solution: allocate larger segments ... internal fragmentation. 4 / 32 another problem virtual space used code We’re reserving physical memory that is not used. physical memory not used? 5 / 32 Let’s try again It’s easier to handle fixed size memory blocks. Can we map a process virtual space to a set of equal size blocks? An address is interpreted as a virtual page number (VPN) and an offset. 6 / 32 Remember the segmented MMU MMU exception no virtual addr. offset yes // < within bounds index + physical address segment table 7 / 32 The paging MMU MMU exception virtual addr. offset // VPN available ? + physical address page table 8 / 32 the MMU exception exception virtual address within bounds page available Segmentation Paging linear address physical address 9 / 32 a note on the x86 architecture The x86-32 architecture supports both segmentation and paging. A virtual address is translated to a linear address using a segmentation table. The linear address is then translated to a physical address by paging. Linux and Windows do not use use segmentation to separate code, data nor stack. The x86-64 (the 64-bit version of the x86 architecture) has dropped many features for segmentation. -

ARM-Architecture Simulator Archulator

Embedded ECE Lab Arm Architecture Simulator University of Arizona ARM-Architecture Simulator Archulator Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Description ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Block Diagram ............................................................................................................................ 2 Component Description .............................................................................................................. 3 Buses ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 µP .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Caches ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Memory ................................................................................................................................................. 3 CoProcessor .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Using the Archulator ...................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 6 : Memory System

Computer Organization and Architecture Chapter 6 : Memory System Chapter – 6 Memory System 6.1 Microcomputer Memory Memory is an essential component of the microcomputer system. It stores binary instructions and datum for the microcomputer. The memory is the place where the computer holds current programs and data that are in use. None technology is optimal in satisfying the memory requirements for a computer system. Computer memory exhibits perhaps the widest range of type, technology, organization, performance and cost of any feature of a computer system. The memory unit that communicates directly with the CPU is called main memory. Devices that provide backup storage are called auxiliary memory or secondary memory. 6.2 Characteristics of memory systems The memory system can be characterised with their Location, Capacity, Unit of transfer, Access method, Performance, Physical type, Physical characteristics, Organisation. Location • Processor memory: The memory like registers is included within the processor and termed as processor memory. • Internal memory: It is often termed as main memory and resides within the CPU. • External memory: It consists of peripheral storage devices such as disk and magnetic tape that are accessible to processor via i/o controllers. Capacity • Word size: Capacity is expressed in terms of words or bytes. — The natural unit of organisation • Number of words: Common word lengths are 8, 16, 32 bits etc. — or Bytes Unit of Transfer • Internal: For internal memory, the unit of transfer is equal to the number of data lines into and out of the memory module. • External: For external memory, they are transferred in block which is larger than a word. -

Advanced X86

Advanced x86: BIOS and System Management Mode Internals Input/Output Xeno Kovah && Corey Kallenberg LegbaCore, LLC All materials are licensed under a Creative Commons “Share Alike” license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ ABribuEon condiEon: You must indicate that derivave work "Is derived from John BuBerworth & Xeno Kovah’s ’Advanced Intel x86: BIOS and SMM’ class posted at hBp://opensecuritytraining.info/IntroBIOS.html” 2 Input/Output (I/O) I/O, I/O, it’s off to work we go… 2 Types of I/O 1. Memory-Mapped I/O (MMIO) 2. Port I/O (PIO) – Also called Isolated I/O or port-mapped IO (PMIO) • X86 systems employ both-types of I/O • Both methods map peripheral devices • Address space of each is accessed using instructions – typically requires Ring 0 privileges – Real-Addressing mode has no implementation of rings, so no privilege escalation needed • I/O ports can be mapped so that they appear in the I/O address space or the physical-memory address space (memory mapped I/O) or both – Example: PCI configuration space in a PCIe system – both memory-mapped and accessible via port I/O. We’ll learn about that in the next section • The I/O Controller Hub contains the registers that are located in both the I/O Address Space and the Memory-Mapped address space 4 Memory-Mapped I/O • Devices can also be mapped to the physical address space instead of (or in addition to) the I/O address space • Even though it is a hardware device on the other end of that access request, you can operate on it like it's memory: – Any of the processor’s instructions