The Magi Initiative: East West

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publications 1427998433.Pdf

THE CHURCH OF ARMENIA HISTORIOGRAPHY THEOLOGY ECCLESIOLOGY HISTORY ETHNOGRAPHY By Father Zaven Arzoumanian, PhD Columbia University Publication of the Western Diocese of the Armenian Church 2014 Cover painting by Hakob Gasparian 2 During the Pontificate of HIS HOLINESS KAREKIN II Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians By the Order of His Eminence ARCHBISHOP HOVNAN DERDERIAN Primate of the Western Diocese Of the Armenian Church of North America 3 To The Mgrublians And The Arzoumanians With Gratitude This publication sponsored by funds from family and friends on the occasion of the author’s birthday Special thanks to Yeretsgin Joyce Arzoumanian for her valuable assistance 4 To Archpriest Fr. Dr. Zaven Arzoumanian A merited Armenian clergyman Beloved Der Hayr, Your selfless pastoral service has become a beacon in the life of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Blessed are you for your sacrificial spirit and enduring love that you have so willfully offered for the betterment of the faithful community. You have shared the sacred vision of our Church fathers through your masterful and captivating writings. Your newest book titled “The Church of Armenia” offers the reader a complete historiographical, theological, ecclesiological, historical and ethnographical overview of the Armenian Apostolic Church. We pray to the Almighty God to grant you a long and a healthy life in order that you may continue to enrich the lives of the flock of Christ with renewed zeal and dedication. Prayerfully, Archbishop Hovnan Derderian Primate March 5, 2014 Burbank 5 PREFACE Specialized and diversified studies are included in this book from historiography to theology, and from ecclesiology to ethno- graphy, most of them little known to the public. -

International Joint Commission for Theological Dialogue Between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches

INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE ORIENTAL ORTHODOX CHURCHES REPORT Twelfth Meeting Rome, January 24 to 31, 2015 The twelfth meeting of the International Joint Commission for Theological Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches took place in Rome from January 24 to 31, 2015, hosted by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. It was chaired jointly by His Eminence Cardinal Kurt Koch, President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, and by His Eminence Metropolitan Bishoy of Damiette. Joining delegates from the Catholic Church were representatives of the following Oriental Orthodox Churches: the Antiochian Syrian Orthodox Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church (Catholicosate of All Armenians), the Armenian Apostolic Church (Holy See of Cilicia), the Coptic Orthodox Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. No representative of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church was able to attend. The two delegations met separately on January 26. Plenary sessions were held on January 27, 28, 29 and 30, each of which began with a brief prayer service based on material prepared for the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. At the beginning of the opening session, Cardinal Koch noted first of all that since the last meeting Pope Francis had appointed a member of the dialogue, Archpriest Levon Boghos Zekiyan, as Apostolic Administrator sede plena of the Archeparchy of Istanbul of the Armenians, elevating him to the dignity of Archbishop. He also congratulated Archbishop Nareg Alemezian on his appointment as Archbishop of the Armenians in Cyprus (Holy See of Cilicia). -

AOOIC Anglican Oriental Orthodox International Commission

Anglican–Oriental Orthodox International Commission Communiqué 2018 The Anglican–Oriental Orthodox International Commission held its seventh meeting from 22–26 October 2018 at the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchal Residence, Atchaneh, Lebanon. The Commission greatly appreciated the generous hospitality of His Holiness Mor Ignatius Aphrem II, Patriarch of Antioch and All the East, and the kindness of the sisters of the Mor Jacob Baradeus Convent, and all those assisting His Holiness. The Commission noted with deep sadness the recent passing of one of its founder-members and its former Oriental Orthodox Co-Chair, His Eminence Metropolitan Bishoy of Damietta. The Commission gave thanks for his contribution to Anglican–Oriental Orthodox relations, and for his leadership in the ecumenical movement. The Commission offered prayers for the repose of his soul, and continues to hold his diocese in its prayers. The Procession and Work of the Holy Spirit, the agreed statement of the 2017 meeting of the Commission, was published in October 2018. It is dedicated to Metropolitan Bishoy, ‘monk, bishop, theologian, champion of the Orthodox faith and unity of the Church’. The members of the Commission welcome the unanimous elections, by its Oriental Orthodox members, of His Eminence Archbishop Angaelos of London as the new Oriental Orthodox Co-Chair and of the Very Revd Dr Roger Akhrass as the new Oriental Orthodox Co- Secretary. The Commission resumed its work on Authority in the Church, with papers on bishops and synods (councils), and the Ecumenical Councils. It seeks to draw on established ecumenical agreements in the framework of this Commission, and the distinctive characteristics of the two families of Churches. -

Res 3 2016 De Gruyter Open.Indd

Ecumenical news / Aktuelles Inter-Orthodox Consultation for a Response to the Faith and Order Text “The Church: Towards a Common Vision” DANIEL BUDA* In 2013 the Commission on Faith and Order of the World Council of Churches (WCC) published the text entitled “The Church: Towards a Com- mon Vision”1 (TCTCV) as a result of several years of research, consultation and discernment in field of ecclesiology. An important part in the process of formulating this document was the consultation of WCC member churches and further Faith and Order Commission constituencies at their different levels. Already when the text reached a preliminary level and has been publi- shed under the title “The Nature and Mission of the Church,”2 churches, aca- demic and ecumenical institutions etc. were invited to formulate comments and proposals for improving the text. A consultation held 2-9 March 2011 in Agia Napa/Paralimni, Cyprus, and hosted by His Eminence Metropolitan Vasilios of Constantia-Ammochostos featured several concrete and precise proposals for redrafting the text.3 The final text of TCTCV incorporated many of the suggestions made at the Agia Napa/Paralimni consultation. The WCC Central Committee in 2012 which received the final ver- sion of TCTCV and sent it also to WCC member churches “to encourage further reflection on the Church and seek their formal responses to the text.” As a response to the call of WCC Central Committee, an inter-orthodox consultation with participation of Eastern and Oriental Orthodox hierarchs, priests, deacons, university professors, lay (male and female) and youth took place in Paralimni, Cyprus from 6-13 October 2016, upon the invitation of WCC and thanks to the gracious hospitality of His Eminence Metropolitan Vasilios of Constantia-Ammochostos. -

Sts. Vartanantz Church

Sts. Vartanantz Church WEEKLY BULLETIN Reverend Father Kapriel Nazarian 402 Broadway, Providence, RI 02909 Pastor Office: 831-6399 Fax: 351-4418 Email: [email protected] Website: stsvartanantzchurch.org Third Day of the Nativity - January 8, 2017 Please Join Us in Worship this Sunday Մասնակցեցէք Ս.Պատարագին` Morning Service 9:30 am Առաւօտեան Ժամերգութիւն 9:30 Divine Liturgy 10:00 am - Sermon 11:15 Ս. Պատարագ 10:00 - Քարոզ 11:15 Armenian Christmas Eve. Service celebrated by Der Kapriel on Thursday, January 5, 2017 "Silent Night" Լուր Քիշեր was sung sweetly by Sareen Khatchadourian on Armenian Christmas Eve. Քրիստոս Ծնաւ եւ Յայտնեցաւ Օրհնեալ է Յայտնութիւնն Քրիստոսի ԶԵզ եւ Մեզ Մեծ Աւետիս Christ was Born and Revealed Blessed is the Manifestation of Christ Great Tidings Unto Us All GOSPEL Matthew 2:13-23 When they had gone, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,” he said, “take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him.” So he got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt, where he stayed until the death of Herod. And so was fulfilled what the Lord said through the prophet: “Out of Egypt I called my son.” When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi. -

Holy See of Cilicia Representative Vannna Kitsinian Der Ohanessian Participates in Meeting of World Council of Churches in Albania

HOLY SEE OF CILICIA REPRESENTATIVE VANNNA KITSINIAN DER OHANESSIAN PARTICIPATES IN MEETING OF WORLD COUNCIL OF CHURCHES IN ALBANIA On October 3-8, 2010, Holy See of Cilicia representative, Vanna Kitsinian Der Ohanessian, Esq. participated in the 50th meeting of the Commission of Churches on International Affairs (“CCIA”), a commission under the umbrella of the World Council of Churches (“WCC”). The WCC is the broadest organization of the world-wide ecumenical movement and a fellowship of more than 350 churches in over 120 countries whose overall goal is to achieve Christian Unity. The CCIA deals primarily with advising the WCC on public policy and advocacy, counseling WCC leaders on programmatic directions, including issues that underlie injustice and social transformation, promoting a peaceful and reconciling role of religion in conflicts and prompting inter-religious dialogue. This year’s CCIA meeting took place in Durres, Albania and was hosted by the Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania. The Church in Albania is unique considering it has re- emerged as a faith community for the past several decades after communist rule. The country was completely isolated from 1944 and consequently the constitutional declaration of Albania as an atheist state in 1967 denied the right to religious liberty and prohibited all religious activities until the fall of communism in 1991. The church seen today in Albania is a testament to the moving story of its rebirth. In no other country in the world, with the exception of China, has a church come back to prominence following virtual extinction by the brutal suppression of its religious activities. -

SEIA NEWSLETTER on the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism ______Number 196: January 31, 2012 Washington, DC

SEIA NEWSLETTER On the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism _______________________________________________________________________________________ Number 196: January 31, 2012 Washington, DC The International Catholic-Oriental attended the meal. turies, currently undertaken by the com- Orthodox Dialogue The Joint Commission held plenary mission since January 2010, is perhaps sessions on January 18, 19, and 21. Each expected to establish good historical un- day began with Morning Prayer. At the derstanding of our churches. We think HE NINTH MEETING OF THE INTER- beginning of the meeting Metropolitan such technical and scholarly selection of NATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION FOR Bishoy congratulated one of the Catholic items for discussion will bring many more THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN T members, Rev. Fr. Paul Rouhana, on his outstanding results beyond the initially THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE recent election as General Secretary of the expected purpose of the Joint Commis- ORIENTAL ORTHODOX CHURCHES TOOK Middle East Council of Churches. sion. Therefore, this theological and spir- PLACE IN ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA, FROM The meeting was formally opened on itual contemplation will not only unveil JANUARY 17 TO 21, 2012. The meeting was hosted by His Holiness Abuna Paulos the morning of January 18 by His Holi- the historical and theological facts that I, Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox ness Patriarch Paulos. In his address to exist in common but also will show us the Tewahedo Church. It was chaired jointly the members, the Patriarch said, “It is with direction for the future. The ninth meeting by His Eminence Cardinal Kurt Koch, great pleasure and gratitude we welcome of the Joint Commission in Addis Ababa President of the Pontifical Council for you, the Co-chairs, co-secretaries and is expected to bring much more progress Promoting Christian Unity, and by His members of the Joint International Com- in your theological examinations of enor- Eminence Metropolitan Bishoy of Dami- mission for Theological Dialogue between mous ecclesiastical issues. -

A Brief Historical Survey of the Catholicosate

1 A BRIEF HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE ARMENIAN APOSTOLIC CHURCH Christianity in Armenia can be traced back to the age of the Apostles. The Apostolic Church of Armenia acknowledges as its original founders two of the twelve Apostles of Christ, St. Thaddeus and St. Bartholomew, who evangelized in Armenia, and were martyred there. It was at the beginning of the fourth century, during the reign of King Trirdates III, and through the missionary efforts of St. Gregory that Christianity was declared and adopted as the official religion of Armenia in 301 A.D. Until the 5th century, Christian worship in Armenia was conducted in Greek or Syriac. In 404 A.D., St. Mesrob together with the Catholicos St. Sahag (387-439), having the financial assistance and collaboration of King Vramshabouh, invented the Armenian alphabet in 404, which became a decisive and crucial event for Armenian Christianity. Soon after with a number of disciples, St. Mesrob worked on the translation of the Bible and a large number of religious and theological works were translated into Armenian, and the golden age of classical Armenian literature began shortly thereafter. This “cultural revolution” gave national identity and led to one of the most creative and prolific periods in the history of Armenian culture. The Armenian Apostolic Church aligns herself with the non- Chalcedonian or with lesser-Eastern-Orthodox churches, namely: Syrian Orthodox Church; Coptic Orthodox Church; Ethiopian Orthodox Church. They all accept the first three Ecumenical Councils of Nicaea (325), Constantinople (381), and Ephesus (431). The Armenian Church has traditionally maintained two Catholicosates: The Catholi-cosate of Etchmiadzin in Armenia, and Catholicosate of Holy See of Cilicia in Antelias-Lebanon. -

A Handbook of Councils and Churches Profiles of Ecumenical Relationships

A HANDBOOK OF COUNCILS AND CHURCHES PROFILES OF ECUMENICAL RELATIONSHIPS World Council of Churches Table of Contents Foreword . vii Introduction . ix Part I Global World Council of Churches. 3 Member churches of the World Council of Churches (list). 6 Member churches by church family. 14 Member churches by region . 14 Global Christian Forum. 15 Christian World Communions . 17 Churches, Christian World Communions and Groupings of Churches . 20 Anglican churches . 20 Anglican consultative council . 21 Member churches and provinces of the Anglican Communion 22 Baptist churches . 23 Baptist World Alliance. 23 Member churches of the Baptist World Alliance . 24 The Catholic Church. 29 Disciples of Christ / Churches of Christ. 32 Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council . 33 Member churches of the Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council . 34 World Convention of Churches of Christ. 33 Evangelical churches. 34 World Evangelical Alliance . 35 National member fellowships of the World Evangelical Alliance 36 Friends (Quakers) . 39 Friends World Committee for Consultation . 40 Member yearly meetings of the Friends World Committee for Consultation . 40 Holiness churches . 41 Member churches of the Christian Holiness Partnership . 43 Lutheran churches . 43 Lutheran World Federation . 44 Member churches of the Lutheran World Federation. 45 International Lutheran Council . 45 Member churches of the International Lutheran Council. 48 Mennonite churches. 49 Mennonite World Conference . 50 Member churches of the Mennonite World Conference . 50 IV A HANDBOOK OF CHURCHES AND COUNCILS Methodist churches . 53 World Methodist Council . 53 Member churches of the World Methodist Coouncil . 54 Moravian churches . 56 Moravian Unity Board . 56 Member churches of the Moravian Unity Board . 57 Old-Catholic churches . 57 International Old-Catholic Bishops’ Conference . -

International Joint Commission for Theological Dialogue Between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches

INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION FOR THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE ORIENTAL ORTHODOX CHURCHES REPORT Seventh Meeting Antelias, Lebanon, January 27 to 31, 2010 The seventh meeting of the International Joint Commission for Theological Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches took place at the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia in Antelias, Lebanon, from January 27 to 31, 2010. The meeting was graciously hosted by His Holiness Aram I, Catholicos of the Holy See of Cilicia. It was chaired jointly by His Eminence Cardinal Walter Kasper, President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, and His Eminence Metropolitan Bishoy of Damiette, General Secretary of the Holy Synod of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Joining delegates from the Catholic Church were representatives of the following Oriental Orthodox Churches: the Coptic Orthodox Church, the Syrian Orthodox Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church (Catholicosate of All Armenians), the Armenian Apostolic Church (Holy See of Cilicia), the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Church, and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church. No representative of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church was able to attend. The two delegations met separately on January 27, and held plenary sessions each day from January 28 to January 30. Each day of the plenary sessions began with a common celebration of Morning Prayer. At its initial session, the members of the Joint Commission considered reactions to and evaluations of the agreed statement that it had issued one year earlier, “Nature, Constitution and Mission of the Church.” This document had been approved for publication by the Joint Commission and is now being considered by the authorities of their churches. -

File Magic-S15067C6.MAG

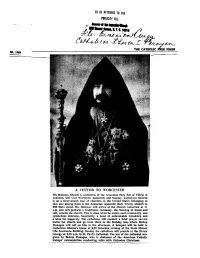

30, 1969 ,..._....;..------=· A VISITOR TO WORCESTER His Holiness Khoren I, catholicos of the Armenian Holy See of Cilicia in Lebanon, will visit Worcester tomorrow and Sunday. Catholicos Khoren is on a three-month tour of churches in the United States belonging to that see; among them is the Armenian Apostolic Holy Trinity Church at 886 Main street. His Holiness will arrive at the Church tomorrow at 11 a.m. and will perform a traditional ceremony, the blessing of bread and salt, outside the church. This is done when he enters each community,. and symbolizes welcome, hospitality, a bond of unbre~kable friendship and a wish for longevity. The catholicos will conduct a brief prayer service inside the church and go from there to the Holiday Inn,-where Bishop Flanagan will call on him in the afternoon. A banquet will· be held in Catholicos Khoren's honor at 6:30 Saturday evening at the State Mutual Life Assurance Building. Sunday the catholicos will preside at the Divine Liturgy at 2:15 p.m. in St. Paul's Cathedral. The use of the cathedral was given by Bishop Flanagan, who is chairman or' the American Catholic bishops' subcommittee conducting talks with Orthodox Christians. TO BE RETURNED TO THE PUBLICITY FILE Diocese of the Armenian Church ··~-~ 63J~ r·'l '~-~f {(: .. (Le;o:dJ~~en;;·,N·:·~~~oo\ .({i,. & ~. l.:..t< f/\.. t\.t.: ( l'· ..' '-;o\- {.: t." ( t:tt ~ 11 A.r~C NEW HAT FOR CARDINAL Richard Cardinal Cushing of Boston wears the "Vegher" presented to him recently by Catholicos Khoren I of the Armenian See of Cilicia. -

Analysis of Canonical Issues in Paratext

Analysis of canonical issues in Paratext Abstract Here is my current analysis of book definitions in Paratext. I have looked at what we have, how that can be improved, and I have added my summary of new books required for Paratext 7 with my proposed 3 letter codes for them. There are many books that need to be added to Paratext. It is important that these issues are addressed before Paratext 7 is implemented. Part 1 This paper first of all analyses the books that are already defined in Paratext. It looks at books in Paratext and draws conclusions. Part 2 Then it recommends some changes for: • books to delete which can be dealt with another way; • Duplicate book to remove; • Books to rename. Part 3 Then the paper looks at books to add to Paratext. Books need to be added are for the following traditions: • Ethiopian • Armenian • Syriac • Latin Vulgate • New Testament codices. Part 4 Then the paper looks at other changes recommended for Paratext relating to: • Help • Book order • Book abbreviations bfbs linguistic computing Page 1 of 41 last updated 25/06/2009 [email protected] Bible Society, Stonehill Green, Westlea, Swindon, UK. SN5 7DG lc.bfbs.org.uk Analysis of canonical issues in Paratext Part 1: Analysis of the current codes in Paratext 1.1 Notes on the Paratext Old Testament Books 01-39 1.1.1 Old Testament books Paratext books 01-39 are for the Old Testament books in the Western Protestant order and based on the names in the English tradition. Here are some notes on problems that have arisen in some Paratext projects for the Old Testament: 1.1.2 Esther (EST) In Catholic and Orthodox Bibles Esther is translated from the longer Septuagint and not the shorter Hebrew book.