Patrick Botts Faculty Mentor: Dr. Andrea Maestrejuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Reading by Grade/Title Fifth and Sixth Grades 2018 Summer

Summer Reading By Grade/Title Fifth and Sixth Grades 2018 Summer Reading Requirements Choose 2 The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate Jacqueline Kelly 830L Fish in a Tree Lynda Mullaly Hunt 550L Inside Out and Back Again Thanhha Lai 800L Out of My Mind Sharon Draper 700L My Side of the Mountain Jean Craighead George 810L Auggie & Me: Three Wonder Stories RJ Palacio 680L (Wonder is suggested before reading this book) The Phantom Tollbooth Norton Juster 1000L Pax Sara Pennypacker 760L Sticks & Stones Abby Cooper 750L Rules Cynthia Lord 670L Ms. Bixby’s Last Day John David Anderson 800L Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story Nora Raleigh Baskin 730L Tuck Everlasting Natalie Babbitt 770L Where the Red Fern Grows Wilson Rawls 700L Seventh Grade: Required reading: Flying Lessons and Other Short Stories edited by Ellen Oh Book of choice list: Classics that Mrs. McDaniel loves: 1. Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech 2. The Westing Game by Ellen Raskin 3. A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle 4. Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor 5. Hatchet by Gary Paulson 6. The Watsons go to Birmingham by Christopher Paul Curtis Modern YA books: 7. Holes by Lois Sachar 8. The Wednesday Wars by Gary D. Schmidt 9. Hoot by Carl Hiaasen 10. Code Talker by Joseph Bruchac 11. A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness Eighth Grade: Required reading: Brown Girl Dreaming by Jaqueline Woodson Book of choice list: Classics that Mrs. McDaniel loves: 1. Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery 2. The Hobbit by J.R.R. -

Kate Fitzgerald

In This Issue: 2020 Young Investigator Awardees pg. 3-9 In Memorium page pg. 14-15 New Member Mini-Bios pg. 19-21 Trials of Interferon Lambda pg. 31 Cytokines 2021 Hybrid Meetin pg. 24-27 Signals THE INTERNATIONAL CYTOKINE & INTERFERON SOCIETY + NEWSLETTER APRIL 2021 I VOLUME 9 I NO. 1 A NOTE FROM THE ICIS PRESIDENT Kate Fitzgerald Dear Colleagues, Greetings from the International Cytokine and Interferon Society! I hope you and your family are staying safe during these still challenging times. Thankfully 2020 is behind us now. We have lived through the COVID-19 pandemic, an event that will continue to impact our lives for some time and likely alter how we live in the future. Despite the obvious difficulties of this past year, I can’t help but marvel at the scientific advances that have been made. With everything from COVID-19 testing, to treatments and especially to the rapid pace of vaccine development, we are so better off today than even a few months back. The approval of remarkably effective COVID-19 vaccines now rolling out in the US, Israel, UK, Europe and across the globe, brings light at the end of the tunnel. The work of many of you has helped shape our understanding of the host response to Sars-CoV2 and the ability of this virus to limit antiviral immunity while simultaneously driving a cytokine driven hyperinflammatory response leading to deadly consequences for patients. The knowledge gained from all of your efforts has been put to good use to stem the threat of this deadly virus. -

2016 Research in Action Awards

TREATMENT ACTION GROUP The Board of Trustees 2016 RESEARCH IN ACTION AWARDS and staff of amfAR, The Foundation Treatment Action Group’s (TAG’s) annual Research in Action Awards honor activists, scientists, philanthropists and creative artists who have made for AIDS Research extraordinary contributions in the fight against AIDS. Tonight’s awards ceremony is a fundraiser to support TAG’s programs and provides a forum for honoring heroes of the epidemic. salute the recipients of the HONOREES LEVI STRAUSS & CO. for advancing human rights and the fight 2016 TAG Research in Action Awards against HIV/AIDS ROSIE PEREZ actor/activist MARGARET RUSSELL award-winning design journalist/editor, Levi Strauss & Co. cultural leader and accomplished advocate for HIV prevention and care BARBARA HUGHES longtime AIDS activist and dedicated Rosie Perez President of TAG’s Board since 1996 HOSTS Margaret Russell JENNA WOLFE lifestyle and fitness expert BRUCE VILANCH comedy writer, songwriter, actor and Emmy ® Barbara Hughes Award winner THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2016 6PM Cocktails and Hors d’Oeuvres 7PM Awards Presentation SLATE www.amfar.org 54 West 21st Street New York City TAG ad 102716.indd 1 10/27/16 3:17 PM TAG 2016 LIMITED ART EDITION RIAA 2016 CO-CHAIRS SCOTT CAMPBELL Executive Director, Elton John AIDS Foundation DICK DADEY Executive Director, Citizens Union JOY TOMCHIN Founder of Public Square Films, Executive Producer of How to Survive a Plague and the upcoming documentary Sylvia and Marsha RIAA 2016 HONORARY CHAIRS 2014 RIAA honoree ALAN CUMMING and GRANT SHAFFER 2009 RIAA honoree DAVID HYDE PIERCE and BRIAN HARGROVE ROSALIND FOX SOLOMON Animal Landscape, 1979 Archival pigment print | 15 1/2 x 15 1/2 inches | 8-ply mat + granite welded metal frame + uv plexi 23 1/2 x 23 inches | Edition of 15 + 3 AP's | ©Rosalind Fox Solomon, www.rosalindsolomon.com RIAA 2016 COMMITTEE Courtesy of Bruce Silverstein Gallery Joy Episalla, Chair for Projects Plus, Inc. -

LFL MAG Medweb.Pdf

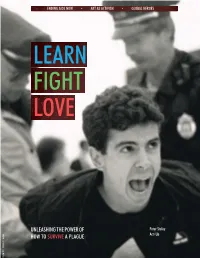

ENDING AIDS NOW * ART AS ACTIVISM * GLOBAL HEROES LEARNLEARN FIGHT LOVE FIGHT LOVE UNLEASHING THE POWER OF Peter Staley PHOTO: © William Lucas Walker PHOTO: HOW TO SURVIVE A PLAGUE Acts Up HTSAPxm_poster_ACADEMY_Jan_2013_v1 1/16/13 3:23 PM Page 1 PHOTO: © Karine Laval © Karine PHOTO: discipline removed from the real world A LETTER FROM of ordinary people. It took up to a dozen years for a new drug to be tested and THE FILMMAKER released. Even after the onset of the AIDS epidemic, with its grim prognosis of just How to Survive a Plague bears witness. 18 months, a hermetic sense of academic The film documents what I saw with my sluggishness prevailed. They knocked on own eyes in those first long dark days of doors at the NIH and FDA, then knocked the worst plague in America—it shows them down when their pleas were both the tragedy and the brilliance not answered. leading up to 1996 when effective That’s how the “inside” forces flooded medication finally made it possible to in and demanded a place at the table think of HIV/AIDS as a chronic condition, for patients and their advocates in every like diabetes. I witnessed all this in my role aspect of medicine and science. Their as a journalist, not an activist. Instead of a task was daunting. In order to become bullhorn or placard, I carried a notepad full partners in the research, they had to and pen. There I am in the background of become experts themselves. I watched these frames. You can see brief glimpses Peter, Mark, Garance, David, and the of me nearly hidden in those crowds of others turn to textbooks and teach activists, pressed against the walls of themselves the fundamentals of science— their meetings or counting their heads as quizzing one another on the basics police officers carted them off, trying to of immunology and virology, cellular stay out of their way. -

TRUE/FALSE FILM FEST 2020 FEATURE FILMS 45365 | Dir. Bill & Turner Ross; 2009; 94 Min (United States) Prod. Bil & Turner

TRUE/FALSE FILM FEST 2020 FEATURE FILMS 45365 | Dir. Bill & Turner Ross; 2009; 94 min (United States) Prod. Bil & Turner Ross It’s 69 degrees and sunny at the Shelby County Fair. Long-haul trucks whiz by, a solo trumpeter takes the stage, and downtown Sidney’s tree-lined main street disappears into the rearview mirror in a stunning opening sequence. Dazzling and earnest, this debut film by Bill and Turner Ross uses the sounds of public radio, marching bands, and police scanners to cleverly collapse time and space, taking us from the weekend weather to a live interview with the 4-H queen first runner-up. Here, in the heart of the Ohio valley, spotted horses prance in their stables, teenage boys race in junk derbies and local politicians canvass door-to-door for their reelections. Filmed over the course of nine months, the camera moves deftly between flirting, freak shows, and football, reminding us that the everyday is extraordinary and “it’s always fun to watch little kids run around with their hogs.” (JA) Aswang | Dir. Alyx Ayn Arumpac; 2019; 85 min (Philippines) Prod. Armi Rae Cacanindin Blood stains the sidewalks as President Duerte undertakes what he calls the “neutralization of illegal drug personalities,” but what citizens of Manilla have come to know as nothing less than a killing spree. In her feature-length debut, Director Alyx Arympac sensitively approaches the trauma that has befallen her subjects: a journalist who fights the government’s lawlessness; a restrained coroner; a brave missionary’s brother who tries to comfort the bereaved families of the dead; and Jomari, who lives on the streets after his parents were jailed. -

Download The

AGING AND HIV THOUGHTS ON PrEP FROM the FIRST PERSON CURED of HIV ARE YOU AT RISK FOR ANAL CANCER? POSITIVELY AWARE THE HIV TREATMENT JOURNAL OF TEST POSITIVE AWARE NETWORK JANUARY+FEBRUARY 2015 LEONG-T RM suRVIVORS ARE Not JUST LIVING loNGER, they’RE KICKING TEZ ANDERSON AND MATT SHARP take on AIDS ASS SURVIVOR SYNDROME This page intentionally left blank. ➤ POSITIVELY AWARE [email protected] CORRE CTING A disease and remind us not to focus exclu- know that all the hard work that goes into CONTRADICTION sively on T-cells and antiretrovirals. compiling such a class A magazine is not IN TERMS —CARL STEIN, MHS, PAC, AAHIVS overlooked. May you be blessed. PHYSiciAN ASSISTANT —C HERYL VITELLO R egarding “Can Hepatitis C Be Sexually OWEN MEDICAL GROUP GATESVILLE, TX Transmitted?” in the November+December SAN FRANCISCO, CA StiGMA 2014 issue: On page 28 Andrew Reynolds responds: I am currently incarcerated at Collins the author writes, Correctional Facility in Collins, New York. “We know that Dear Carl and other readers, I want to tell how I was a target of HIV stigma HCV is present in Thank you for the careful (“Have you ever been the target of HIV stigma blood, but there reading and feedback on the or discrimination?” poll, September+October is no evidence article “Can Hepatitis C Be 2014). It started right in my own neighbor- that it is found Sexually Transmitted?” You are hood after I disclosed to someone who I in semen....” On absolutely correct in my contra- thought was a friend. He eventually told some page 29 the author diction on pages 28 and 29. -

GORE VIDAL the United States of Amnesia

Amnesia Productions Presents GORE VIDAL The United States of Amnesia Film info: http://www.tribecafilm.com/filmguide/513a8382c07f5d4713000294-gore-vidal-the-united-sta U.S., 2013 89 minutes / Color / HD World Premiere - 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, Spotlight Section Screening: Thursday 4/18/2013 8:30pm - 1st Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/19/2013 12:15pm – P&I Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 6 Saturday 4/20/2013 2:30pm - 2nd Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/26/2013 5:30pm - 3rd Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 4 Publicity Contact Sales Contact Matt Johnstone Publicity Preferred Content Matt Johnstone Kevin Iwashina 323 938-7880 c. office +1 323 7829193 [email protected] mobile +1 310 993 7465 [email protected] LOG LINE Anchored by intimate, one-on-one interviews with the man himself, GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATS OF AMNESIA is a fascinating and wholly entertaining tribute to the iconic Gore Vidal. Commentary by those who knew him best—including filmmaker/nephew Burr Steers and the late Christopher Hitchens—blends with footage from Vidal’s legendary on-air career to remind us why he will forever stand as one of the most brilliant and fearless critics of our time. SYNOPSIS No twentieth-century figure has had a more profound effect on the worlds of literature, film, politics, historical debate, and the culture wars than Gore Vidal. Anchored by intimate one-on-one interviews with the man himself, Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary is a fascinating and wholly entertaining portrait of the last lion of the age of American liberalism. -

Forget Burial: Illness, Narrative, and the Reclamation of Disease

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Forget Burial: Illness, Narrative, and the Reclamation of Disease Marty Melissa Fink The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2168 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Forget Burial Illness, Narrative, and the Reclamation of Disease by Marty (Melissa) Fink A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 ii © 2010 MARTY MELISSA FINK All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Robert Reid-Pharr Date Chair of Examining Committee Steven Kruger Date Executive Officer Robert Reid-Pharr Steven Kruger Barbara Webb Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Forget Burial: Illness, Narrative, and the Reclamation of Disease by Marty Fink Advisor: Robert Reid-Pharr Through a theoretical and archival analysis of HIV/AIDS literature, this dissertation argues that the AIDS crisis is not an isolated incident that is now “over,” but a striking culmination of a long history of understanding illness through narratives of queer sexual decline and national outsiderhood. -

Annual Report 2019 - 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 - 2020 1 2 ABOUT US Callen-Lorde is the global leader in LGBTQ healthcare. Since the days of Stonewall, we have been transforming lives in LGBTQ communities through excellent comprehensive care, provided free of judgment and regardless of ability to pay. In addition, we are continuously pioneering research, advocacy and education to drive positive change around the world, because we believe healthcare is a human right. CONTENTS History and Namesakes . 4 A Letter from our Executive Director Wendy Stark . 6 A Letter from our Board Chair Lanita Ward-Jones ������������������������������������������������������������ 7 COVID-19 Impact . 8 Callen-Lorde Brooklyn ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10 Advocacy & Policy ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10 The Keith Haring Nurse Practitioner Postgraduate Fellowship in LGBTQ+ Health ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 12 Callen-Lorde by the Numbers . 14 Senior Staff and Board of Directors ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 16 Howard J. Brown Society . .17 John B. Montana Society �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������17 -

The AIDS Epidemic at 20 Years: in the FIRST SIX MONTHS… SELECTED MILESTONES

THE HENRY J. KAISER FAMILY 2001 Number of U.S. AIDS cases Number of U.S. AIDS-related Estimated number of Estimated number of people Estimated number of FOUNDATION reported since the beginning deaths reported since the Americans living with living with HIV/AIDS globally cumulative AIDS-related of the epidemic beginning of the epidemic HIV/AIDS deaths throughout the world 2001 The AIDS Epidemic At 20 Years: IN THE FIRST SIX MONTHS… SELECTED MILESTONES Major Sources Menlo Park, CA On June 5, 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued its 2400 Sand Hill Road African American AIDS Policy and Training Institute, The NIA first warning about a relatively rare form of pneumonia among a small group of Menlo Park, CA 94025 Plan, 1999; AIDS Memorial Quilt History, www.aidsquilt.com; young gay men in Los Angeles, which was later determined to be AIDS-related. 650 854-9400 tel AIDS Project Los Angeles, APLA History, www.apla.org; AIDS-Arts 650 854-4800 fax Timeline, www.ArtistswithAIDS.org; American Foundation for AIDS Over the past 20 years, there have been many milestones in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Research (amfAR); Arno, P. and Frieden, K., Against the Odds: Each of us has our own history that no single set of milestones can adequately The Story of AIDS Drug Development, Politics, and Profits, Washington, DC reflect. Yet, certain events stand out. They captured public attention, causing the Harper Collins: New York, 1992; Being Alive Los Angeles; Global 1450 G Street NW Health Council; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS Suite 250 nation – and indeed the world – to stop and take notice. -

Randy Shilts Papers

RANDY SHILTS PAPERS 1955-1994 Collection number: GLC 43 The James C. Hormel Gay and Lesbian Center San Francisco Public Library 2005 Randy Shilts Papers GLC 43 p. 2 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 3-4 Biography p. 5 Scope and Content p. 6 Series Description p. 7-8 Container Listing p. 9-43 Series 1: Personal Papers, 1965-1994 Series 2: Professional Papers, 1975-1994 Series 2a: Journalism, 1975-1994 p.9-19 Series 2b: Books, 1980-1994 Series 3: Gay Research Files, 1973-1994 Series 4: AIDS Research Files, 1983-1994 Series 5: Audio-visual Materials, 1955-1994 Randy Shilts Papers GLC 43 p. 3 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library INTRODUCTION Provenance The Randy Shilts Papers were donated to The San Francisco Public Library by the Estate of Randy Shilts in 1994. Access The collection is open for research and available in the San Francisco History Center on the 6th Floor of the Main Library. The hours are: Tues.-Thurs. 10 a.m.-6 p.m., Fri. 12 noon-6 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.-6 p.m. and Sun. 12 noon-5 p.m. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts should be addressed to Michael Denneny, Literary Executor, St. Martin’s Press, 175 – 5th Avenue, New York, NY, 10010. Collection Number GLC 43 Size ca. 120 cu. ft. Materials Stored Separately Photographs, slides and negatives are stored with the San Francisco History Center’s Historical Photograph Collection and are available on Tuesdays and Thursdays 1-5 p.m. -

William C. Thompson, Jr

WILLIAM C. THOMPSON, JR. NEW YORK CITY COMPTROLLER Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender DIRECTORY OF SERVICES AND RESOURCES NEW YORK METROPOLITAN AREA JUNE 2005 www.comptroller.nyc.gov June 2005 Dear Friend, I am proud to present the 2005 edition of our annual Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Directory of Services and Resources. I know it will continue to serve you well as an invaluable guide to all the New York metropolitan area has to offer the LGBT community, family and friends. Several hundred up-to-date listings, most with websites and e-mail addresses, are included in this year’s Directory. You’ll find a wide range of community organizations, health care facilities, counseling and support groups, recreational and cultural opportunities, houses of worship, and many other useful resources and contacts throughout the five boroughs and beyond. My thanks to the community leaders, activists and organizers who worked with my staff to produce this year’s Directory. Whether you consult it in book form or online at www.comptroller.nyc.gov, I am sure you’ll return many times to this popular and comprehensive resource. If you have questions or comments, please contact Alan Fleishman in my Office of Research and Special Projects at (212) 669-2697, or send us an email at [email protected]. I look forward to working together with you as we continue to make New York City an even better place to live, work and visit. Very truly yours, William C. Thompson, Jr. PHONE FAX E-MAIL WEB LINK * THE CENTER, 208 WEST 13TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10011 National gay/lesbian newsmagazine.