Unending Stream of Life”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALL-VIRGINIA BAND and ORCHESTRA Saturday, April 8, 2017

Virginia Band and Orchestra Directors’ Association ALL-VIRGINIA BAND and ORCHESTRA Saturday, April 8, 2017 Charles J. Colgan, Sr. High School Center for Fine and Performing Arts Manassas, VA Concert Band: Jamie Nix, Columbus State University Symphonic Band: Gary Green, the University of Miami Orchestra: Anthony Maiello, George Mason University Virginia Band and Orchestra Directors Association Past Presidents Stephen H. Rice (2014-2016) H. Gaylen Strunce (1974-1976) Allen Hall (2012-2014) Carroll R. Bailey (1972-1974) Keith Taylor (2010-2012) James Lunsford (1970-1972) Doug Armstrong (2008-2010) James Simmons (1968-1970) Rob Carroll (2006-2008) Harold Peterson (1966-1968) Denny Stokes (2004-2006) David Mitchell (1964-1966) T. Jonathan Hargis (2002-2004) John Perkins (1962-964) Jack Elgin (2000-2002) Ralph Shank (1960-1962) Joseph Tornello (1998-2000) Gerald M. Lewis (1958-1960) Linda J. Gammon (1996-1998) Leo Imperial (1956-1958) Stanley R. Schoonover (1994-1996) Philip J. Fuller (1953-1956) Dwight Leonard (1992-1994) Clyde Duvall (1952-1953) Diana Love (1990-1992) Russell Williams (1950-1952) Steve King (1988-1990) Sidney Berg (1948-1950) Scott Lambert (1986-1988) William Nicholas (1946-1948) Carl A. Bly (1984-1986) Sharon B. Hoose (1944-1946) Vincent J. Tornello (1982-1984) J.H. Donahue, Jr. (1943-1944) Daniel J. Schoemmell (1980-1982) G.T. Slusser (1942-1943) Edward Altman (1978-1980) Fred Felmet, Jr. (1941-1942) Fred Blake (1976-1978) Sharon B. Hoose (1940-1941) Gilbert F. Curtis (1930-1940) Virginia Band and Orchestra Directors Association 75th Anniversary In recognition of the 75th anniversary of the Virginia Band and Orchestra Directors Association, three works were commissioned to be written by composers with ties to Virginia. -

The Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano (1988) by David Maslanka

THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE LOUISE OLIN (Under the Direction of Kenneth Fischer) ABSTRACT In recent years, the Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano by David Maslanka has come to the forefront of saxophone literature, with many university professors and graduate students aspiring to perform this extremely demanding work. His writing encompasses a range of traditional and modern elements. The traditional elements involved include the use of “classical” forms, a simple harmonic language, and the lyrical, vocal qualities of the saxophone. The contemporary elements include the use of extended techniques such as multiphonics, slap tongue, manipulation of pitch, extreme dynamic ranges, and the multitude of notes in the altissimo range. Therefore, a theoretical understanding of the musical roots of this composition, as well as a practical guide to approaching the performance techniques utilized, will be a valuable aid and resource for saxophonists wishing to approach this composition. INDEX WORDS: David Maslanka, saxophone, performer’s guide, extended techniques, altissimo fingerings. THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE OLIN B. Mus. Perf., Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University, Australia, 2000 M.M., The University of Georgia, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2006 © 2007 Camille Olin All Rights Reserved THE SONATA FOR ALTO SAXOPHONE AND PIANO (1988) BY DAVID MASLANKA: AN ANALYTIC AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE. by CAMILLE OLIN Major ProfEssor: KEnnEth FischEr CommittEE: Adrian Childs AngEla JonEs-REus D. -

The Wicker Husband Education Pack

EDUCATION PACK 1 1 Contents Introduction Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: The Watermill’s Production of The Wicker Husband ........................................................................ 4 A Brief Synopsis.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Character Profiles…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....…8 Note from the Writer…………………………………………..………………………..…….……………………………..…………….10 Interview with the Director ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..………….. 13 Section 2: Behind the Scenes of The Watermill’s The Wicker Husband …………………………………..… ...... 15 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................................................................... 16 An Interview with The Musical Director .................................................................................................................. .20 The Design Process ......................................................................................................................................................... 21 The Wicker Husband Costume Design ...................................................................................................................... 23 Be a Costume Designer……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..25 -

Keyboard & Instrumental

Keyboard & Instrumental GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. New THRee PSALM PRELUDES FOR ORGAN Raymond Haan This set of three preludes is based on psalm texts—“Repose” based on Psalm 4:8, “Contemplation” based on Psalm 8:3a, 4a, and “Meditation” based on Psalm 143:5. The pieces can be used as a set or as individual move- ments. Extensive registration suggestions and nuance of dynamics are included. Contents: Repose • Contemplation • Meditation G-8088 ......................................................................... $12.00 LORD, I WANT TO BE A CHRISTIAN FOR ORGAN AND FLUTE arr. Kenneth Dake Kenneth Dake’s arrangement for flute and organ is based on the familiar African American spiritual “Lord, I Want to Be a Christian.” This charming piece is highly accessible for both parts and offers endless expressive possibilities for interpretation. Perfect for a brief moment of reflection and meditation. G-8184 ......................................................................... $10.00 RESIGNATION MY ShePheRD WILL SUPPLY MY NeeD FOR ORGAN AND VIOLA OR HORN IN F arr. Kenneth Dake Originally written for well-known violist Lawrence Dutton, this beautiful arrangement for viola and organ meanders gently as if floating on a soft summer breeze. The peaceful repose of this work makes it perfect for any reflective moment in your worship service. A part for horn in F is also provided. G-8185 .......................................................................... $12.00 HIS EYE IS ON The SPARROW FOR ORGAN AND HORN IN F OR CLARINET IN B< Charles H. Gabriel arr. Kenneth Dake This meditative piece based on Matthew 6:26 and John 14:1, 27 employs the tender hymn tune sparrow. Scored for horn in F and organ, both parts begin in a quiet, thoughtful manner before soaring to a majestic climax and then returning to the opening mood. -

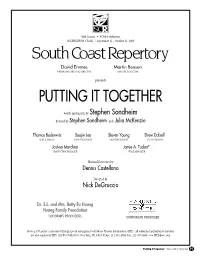

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Maslanka Symphony No. 10

Wind Ensemble Presents Maslanka Symphony No. 10 World Premiere Scott Hagen, conductor Tuesday, April 3, 2018 Libby Gardner Concert Hall Pre-Concert Discussion: 6:45 p.m. Performance: 7:30 p.m. Program (Please hold applause until the end of each section and turn off all electronic devices that could disrupt the concert.) First Light David Maslanka (1943-2017) The Seeker David Maslanka Intermission Symphony No. 10 : The River of Time David Maslanka I. Alison with Matthew Maslanka II. Mother and Boy Watching the River of Time (1982- ) III. David IV. One Breath in Peace Please join us immediately following the concert for a reception in Thompson Chamber Music Hall Wind Ensemble Personnel Piccolo Bass Clarinet Bass Trombone Ali Parra Raymond Hernandez Peyton Wong Flute Contra Bass Clarinet Euphonium Mitchell Atencio Carla Ray Michael Bigelow* Sara Beck Matthew Maslanka Ali Parra Saxophone Garret Woll Diego Plata* Cameron Carter McKayla Wolf Max Ishihara Tuba Chloe Wright David Kidd James Andrus Timothy Kidder Matthew Lindahl* Oboe Lisa Lamb Brenden McCauley Haehyun Jung Erik Newland* Erika Qureshi* Jordan Wright Timpani Yolane Rodriguez Andy Baldwin Robin Vorkink Horn Taylor Blackley Percussion English Horn Sean Dulger Troy Irish Robin Vorkink Korynn Fink Nick Montoya Bradley Sampson Cris Stiles Bassoon Kaitlyn Seymour* Olivia Torgersen Hans Fronberg Amber Tuckness Monah Valentine Dylan Neff* Taylor Van Bibber Brandon Williams* Kylie Lincoln* Trumpet Piano Contra Bassoon Zach Buie* Carson Malen Hans Fronberg Jacob Greer Zach Janis Celeste Eb Clarinet Eddie Johnson McKayla Wolf Maggie Burke Reed LeCheminant Peyden Shelton String Bass Clarinet George Voellinger Hillary Fuller Maggie Burke Jacob Whitchurch Myroslava Hagen Elihue Wright Harp Janelle Johnson Melody Cribbs* Samuel Noyce Trombone Alex Sadler Shaun Hellige *principal player Michal Tvrdik Ammon Helms* Jairo Velazquez* Alex Hunter* Erin Voellinger Brian Keegan This performance and recording project are genersously supported by the Thomas D. -

An Examination of David Maslanka's

DEPICTION THROUGH EVOCATION, REPRESENTATION, AND INTROSPECTION: AN EXAMINATION OF DAVID MASLANKA’S UNACCOMPANIED MARIMBA SOLOS Corey R. Robinson, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 201 8 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Warren Henry, Committee Member Christopher Deane, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John W. Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Robinson, Corey R. Depiction through Evocation, Representation, and Introspection: An Examination of David Maslanka’s Unaccompanied Marimba Solos. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2018, 94 pp., 48 figures, bibliography, 46 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to provide connections between a formal motivic analysis and the programmatic content of David Maslanka’s three works for unaccompanied marimba: Variations on Lost Love (1977), My Lady White (1980), and A Solemn Music (2013). A comparison of the compositional process of each of these works is proposed through terms of Maslanka’s use of depiction. Depiction is the action or result of representing through drawing, painting, or other art form, in this case, music. In each work for unaccompanied marimba, Maslanka uses this process of depiction in a unique way. The depictive mediums are categorized as evocative, representative, and introspective and these distinct approaches to depiction lead to three drastically different musical works. The different methods of depicting source materials are the distinguishing characteristics that separate these three works for solo marimba. -

Tune Name Arranger Page Volume Hymn Title Allein Gott in Der Hoh Albrecht, Timothy 6 Easter All Glory Be to God on High Alleluia No

Tune Name Arranger Page Volume Hymn Title Allein Gott In Der Hoh Albrecht, Timothy 6 Easter All Glory Be to God on High Alleluia No. 1 Honore, Jeffrey 9 Easter Alleluia, Alleluia, Give Thanks Bridegroom Biery, James 14 Easter Like the Murmer of the Dove's Song Bryn Calfaria Haller, William 18 Easter Look, the Sight is Glorious Christ Arose Ferguson, John 21 Easter Up from the Grave He Arose Christ Ist Erstanden Leupold, Anton Wilhelm 24 Easter Christ Is Arisen Crimond Harbach, Barbara 27 Easter The Lord's My Shepherd Cristo Vive (Central) Farlee, Robert Buckley 32 Easter Christ Is Risen, Christ Is Living Den Signede Dag Wold, Wayne L. 36 Easter O Day Full of Grace Down Ampney Sedio, Mark 39 Easter Come Down, O Love Divine Duke Street Held, Wilbur 42 Easter I Know that My Redeemer Lives! Dunlap's Creek Biery, James 45 Easter We Walk by Faith and Not by Sight Earth And All Stars Kolander, Keith 49 Easter Earth And All Stars Easter Hymn Powell, Robert J. 53 Easter Jesus Christ is Risen Today Easter Hymn Goemanne, Noel 57 Easter Jesus Christ is Risen Today Engelberg Cherwien, David M. 60 Easter We Know That Christ is Raised Fortunatus Neswick, Bruce 66 Easter Welcome, Happy Morning! Gaudeamus Pariter Farlee, Robert Buckley 76 Easter Come, You Faithful, Raise the Strain Gelobt Sei Gott Leavitt, John 79 Easter Good Christian Friends, Rejoice and Sing Jesus, Meine Zuversicht Leupold, Anton Wilhelm 81 Easter Jesus Lives! The Victory's Won! Judas Maccabaeus Porter, Emily Maxson 83 Easter Thine Is the Glory Lasst Uns Erfreuen Sedio, Mark 87 Easter Now All the Vault of Heaven Resounds Llanfair Powell, Robert J. -

Illumination

DAVID MASLANKA Illumination OVERTURE FOR BAND ILLUMINATION Overture for Band selected works for high school wind ensemble by david maslanka Rollo Takes a Walk • 1980 Prelude on a Gregorian Tune • 1981 Montana Music: Chorale Variations • 1993 Laudamus Te • 1994 A Tuning Piece • 1995 Heart Songs • 1997 Hell’s Gate • 1997 Morning Star • 1997 Tears • 1997 Alex and the Phantom Band • 2002 Testament • 2002 Mother Earth • 2003 Traveler • 2003 Give Us This Day • 2006 Procession of the Academics • 2007 Unending Stream of Life • 2007 Liberation • 2010 Requiem • 2013 On This Bright Morning • 2013 Hymn for World Peace • 2014 Perusal scores, full recordings, and purchasing information available at davidmaslanka.com DAVID MASLANKA Illumination OVERTURE FOR BAND ( 2013 ) TRANSPOSED PERFORMING SCORE MASLANKA PRESS NEW YORK Copyright © 2014 by Maslanka Press Version 1.0 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. Individuals who purchase the music may create a physical or electronic copy for personal backup or ease of use. David Maslanka and Maslanka Press are members of the American Society for Composers, Authors and Publishers (ascap). Public performances of this work must be licensed through ascap. See www.ascap.com for more information. First published in 2014 by Maslanka Press. maslanka press 420 West Fifty-sixth Street #10 New York City, ny 10019 usa www.maslankapress.com This is the initial release of this work. Any errata may be found on this work’s page at www.maslankapress.com. mp-2013.12-1.0-ps Designed, engraved, and printed in the United States. -

APPROVED: Thomas Clark, Major Professor Ron

AN EXAMINATION OF DAVID MASLANKA’S MARIMBA CONCERTI: ARCADIA II FOR MARIMBA AND PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE AND CONCERTO FOR MARIMBA AND BAND, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF K. ABE, M. BURRITT, J. SERRY, AND OTHERS Michael L. Varner, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 1999 APPROVED: Thomas Clark, Major Professor Ron Fink, Major Professor John Michael Cooper, Minor Professor William V. May, Interim Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Varner, Michael L., An Examination of David Maslanka’s Marimba Concerti: Arcadia II for Marimba and Percussion Ensemble and Concerto for Marimba and Band, A Lecture Recital, Together with Three Recitals of Selected Works of K. Abe, M. Burritt, J. Serry, and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 1999, 134 pp., 62 illustrations, bibliography, 40 titles. Although David Maslanka is not a percussionist, his writing for marimba shows a solid appreciation of the idiomatic possibilities developed by recent innovations for the instrument. The marimba is included in at least eighteen of his major compositions, and in most of those it is featured prominently. Both Arcadia II: Concerto for Marimba and Percussion Ensemble and Concerto for Marimba and Band display the techniques and influences that have become characteristic of his compositional style. However, they express radically different approaches to composition due primarily to Maslanka’s growth as a composer. Maslanka’s traditional musical training, the clear influence of diverse composers, and his sensitivity to extra-musical influences such as geographic location have resulted in a very distinct musical style. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

Hymn Tune Hymn Tune Common Title 1 Aberystwyth Savior

TO DIAL A HYMN NUMBER: While pressing the HYMN PLAYER piston, press General pistons. (Zero is piston #10). Press PLAY. After the intro and each verse press PLAY. (PEDALS ARE DISABLED DURING HYMN PLAYING). TO PLAY A CONTINUOUS PRELUDE: Rotate the SELECT knob to MODE. Select General or Christmas. Press PLAY for continuous play. HYMN TUNE HYMN TUNE COMMON TITLE 1 ABERYSTWYTH SAVIOR, WHEN IN DUST TO YOU (THEE) 2 ACK, VAD AR DOCK LIVET HAR JESUS, IN THY DYING WOES 3 ADELAIDE HAVE THINE OWN WAY 4 ADESTES FIDELES O COME, ALL YE FAITHFUL 5 ALL IS WELL IT IS WELL WITH MY SOUL 5 ALL IS WELL WHEN PEACE LIKE A RIVER 6 ALL THE WAY ALL THE WAY MY SAVIOR LEADS ME 7 ALL TO CHRIST ALL TO CHRIST 8 AMERICA GOD BLESS OUR NATIVE LAND 9 AMSTERDAM OPEN LORD MY INWARD EAR 9 AMSTERDAM PRAISE THE LORD WHO REIGNS ABOVE 9 AMSTERDAM RISE, MY SOUL, AND STRETCH THY WINGS 10 ANGEL'S STORY ANGEL'S STORY 11 ANGELIC SONGS ANGELIC SONGS 12 ANTIOCH JOY TO THE WORLD 13 AR HYD Y NOS FOR THE FRUITS OF ALL CREATION 13 AR HYD Y NOS DAY IS DONE 13 AR HYD Y NOS GO, MY CHILDREN, WITH MY BLESSING 13 AR HYD Y NOS GOD, WHO MADE THE EARTH AND HEAVEN 14 ARLINGTON I'M NOT ASHAMED TO OWN MY LORD 15 ASCEND TO ZION'S ASCEND TO ZION'S HIGHEST 16 ASH GROVE SENT FORTH BY GOD'S BLESSING 16 ASH GROVE LET ALL THINGS NOW LIVING 17 ASSAM I HAVE DECIDED TO FOLLOW JESUS 18 ASSURANCE BLESSED ASSURANCE 19 AURELIA O FATHER, ALL CREATING 19 AURELIA O LIVING BREAD FROM HEAVEN 19 AURELIA THE CHURCH'S ONE FOUNDATION 20 AUSTRIAN HYMN GLORIOUS THINGS OF YOU ARE SPOKEN 20 AUSTRIAN HYMN PRAISE THE LORD! O HEAVENS