Us Navy Dreadnoughts 1914–45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Japanese Submarine 1124

REPORT JAPANESE SUBMARINE 1124 Mike McCarthy Maritime Archaeology Department WAMaritime Museum Cliff Street, Fremantle, WA 6160 October 1990 With research, advice and technical assistance from Captain David Tomlinson Or David Ramm Or J. Fabris Or Thomas O. Paine Mr Garrick Gray Mr George G. Thompson Mr Henri Bourse Mr J. Bastian Mr P.J. Washington RACAL The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade The Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories Underwater Systems Australia Report-Department of Maritime Archaeology, Western Australian Museum, No. 43 2 Background to the report In July 1988, a wreck believed to be the SS Koombanah, which disappeared with all hands in waters off Western Australia in 1921, was officially reported to the W. A. Museum and the federal government by Captain David Tomlinson, (Master/owner of the Darwin based Research Vessel Flamingo Bay) and Mr Mike Barron, a Tasmanian associate of Tomlinson's, fr;om the Commonwealth Fisheries. In order to facilitate an inspection of the site, it was decided on analysis of the available options and in the light of the W.A. Museum's policy of involving the finders where possible, to join with Messrs Tomlinson and Barron in an inspection out of Darwin on board the RV Flamingo Bay, a very well equipped and most suitable vessel for such a venture. Due to the depth of the water in which the site lay and the distance off shore, this required not only the charter of Flamingo Bay which normally runs at circa $2000 per day, but also the hire of a sophisticated position fixing system, a Remote Operated Submersible Vehicle with camera (ROV), echo sounder and side scan sonar. -

Japanese Heavy Cruiser Takao, 1937-1946 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JAPANESE HEAVY CRUISER TAKAO, 1937-1946 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janusz Skulski | 92 pages | 19 Apr 2014 | Kagero Oficyna Wydawnicza | 9788362878901 | English | Lublin, Poland Japanese Heavy Cruiser Takao, 1937-1946 PDF Book Heavy Cruiser Aoba. The Japanese had probably the best cruisers of the early Pacific War era. Japanese 8 in Takao class heavy cruiser Chokai in Related sponsored items Feedback on our suggestions - Related sponsored items. Articles Most Read Fokker D. However, Kirishima was quickly disabled by Washington and sank a few hours later. Ibuki — similar to Mogami. The action took place at night of October Another round of modernization began after the battle of the Philippine Sea in June Items On Sale. Japanese Battleships — Once again, the nightfighting skills of the Japanese wreaked havoc with the American ships when they confronted one another in Iron Bottom Sound off the northeast coast of Guadalcanal. Admiral Graf Spee. As the flagship of Vice Admiral Mikawa Gunichi, she played a central role in the Japanese victory at Savo Island, although she also received the most damage of any Japanese ship present — American cruisers achieved several hits, killing 34 crewmen. Takao was so badly damaged that it was considered impossible to send her back to Japan any time soon for full repairs. Japanese Heavy Cruiser Takao — Name required. The Japanese Aircraft Carrier Taiho. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Propulsion was by 12 Kampon boilers driving four sets of single-impulse geared turbine engines, with four shafts turning three-bladed propellers. Heavy Cruiser Aoba. -

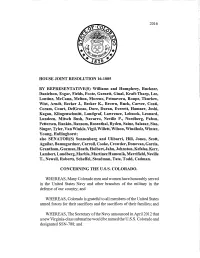

House Joint Resolution 16-1005 by Representative(S

2016 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 16-1005 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Williams and Humphrey, Buckner, Danielson, Esgar, Fields, Foote, Garnett, Ginal, Kraft-Tharp, Lee, Lontine, McCann, Melton, Moreno, Primavera, Roupe, Thurlow, Wist, Arndt, Becker J., Becker K., Brown, Buck, Carver, Conti, Coram, Court, DelGrosso, Dore, Duran, Everett, Hamner, Joshi, Kagan, Klingenschmitt, Landgraf, Lawrence, Lebsock, Leonard, Lundeen, Mitsch Bush, Navarro, Neville P., Nordberg, Pabon, Pettersen, Rankin,Ransom, Rosenthal, Ryden, Saine, Salazar, Sias, Singer, Tyler, VanWinkle, Vigil, Willett, Wilson~ Windholz, Winter, Young, Hullinghorst; also SENATOR(S) Sonnenberg and Ulibarri, Hill, Jones, Scott, Aguilar, Baumgardner,Carroll, Cooke, Crowder,Donovan, Garcia, Grantham, Guzman, Heath, Holbert,Jahn,Johnston, Kefalas, Kerr, Lambert,Lundberg, Marble, MartinezHumenik, Merrifield, Neville T., Newell, Roberts, Scheffel;Steadman, Tate, Todd, Cadman. CONCERNING THE V.S.S. COLORADO. WHEREAS, Many Colorado men and women have honorably served in the United States Navy and other branches of the military in the defense ofour country; and WHEREAS, Colorado is grateful to all members ofthe United States armed forces for their sacrifices and the sacrifices oftheir families; and WHEREAS, The Secretary ofthe Navy announced in April 2012 that a newVirginia-class submarine would be namedthe U.S.S. Colorado and designated SSN-788; and WHEREAS, The U.S.S. Colorado will stretch 377 feet and, in addition to its traditional attack submarine roles, will have accommodations for Navy SEALs and carry Tomahawk missiles with a striking distance of900 miles; and WHEREAS, Ithas been nearly two generations since a United States naval warship has borne the proud name ofthe great state ofColorado; and WHEREAS, This will be the fourth United States naval warship so christened, following the great traditions of the battleship U.S.S. -

216 Allan Sanford: Uss Ward

#216 ALLAN SANFORD: USS WARD Steven Haller (SH): My name is Steven Haller, and I'm here with James P. Delgado, at the Sheraton Waikiki Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii. It's December 5, 1991, at about 5:25 PM. And we have the pleasure to be interviewing Mr. Allan Sanford. Mr. Sanford was a Seaman First Class on the USS WARD, at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. Mr.[Sanford], Ward's gun fired what is in essence the first shot of World War II, and so it's a great pleasure to be able to be talking with you today. We're going to be doing this tape as a part of the National Park Service and ARIZONA Memorial's oral history program. We're doing it in conjunction with KHET-TV in Honolulu. So thanks again for being with us today, Mr. Sanford. Allan Sanford: It's a pleasure to be here. SH: Good. How did you get into the Navy? AS: I joined the Naval reserve unit in St. Paul, Minnesota and with two others of my classmates in high school. And we enjoyed the meetings, and uniforms, and drills, and it was a nice social activity that was a little more mature than some of the high school activities that we had participated in. So we enjoyed the meetings of the St. Paul Naval reserve. And we called it also the Minnesota Naval Militia. However, in September 1940, the commanding officer of the unit came to the meeting and said, "Attention to orders, the Minnesota Naval Militia is hereby made part of the U.S. -

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue IV Fall 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical Society

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume V Issue IV Fall 2016 Saber and Scroll Historical Society 1 © Saber and Scroll Historical Society, 2018 Logo Design: Julian Maxwell Cover Design: Cincinnatus Leaves the Plow for the Roman Dictatorship, by Juan Antonio Ribera, c. 1806. Members of the Saber and Scroll Historical Society, the volunteer staff at the Saber and Scroll Journal publishes quarterly. saberandscroll.weebly.com 2 Editor-In-Chief Michael Majerczyk Content Editors Mike Gottert, Joe Cook, Kathleen Guler, Kyle Lockwood, Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley, Jack Morato, Chris Schloemer and Christopher Sheline Copy Editors Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley Proofreaders Aida Dias, Frank Hoeflinger, Anne Midgley, Michael Majerczyk, Jack Morato, John Persinger, Chris Schloemer, Susanne Watts Webmaster Jona Lunde Academic Advisors Emily Herff, Dr. Robert Smith, Jennifer Thompson 3 Contents Letter from the Editor 5 Fleet-in-Being: Tirpitz and the Battle for the Arctic Convoys 7 Tormod B. Engvig Outside the Sandbox: Camels in Antebellum America 25 Ryan Lancaster Aethelred and Cnut: Saxon England and the Vikings 37 Matthew Hudson Praecipitia in Ruinam: The Decline of the Small Roman Farmer and the Fall of the Roman Republic 53 Jack Morato The Washington Treaty and the Third Republic: French Naval 77 Development and Rivalry with Italy, 1922-1940 Tormod B. Engvig Book Reviews 93 4 Letter from the Editor The 2016 Fall issue came together quickly. The Journal Team put out a call for papers and indeed, Saber and Scroll members responded, evidencing solid membership engagement and dedication to historical research. This issue contains two articles from Tormod Engvig. In the first article, Tormod discusses the German Battleship Tirpitz and its effect on allied convoys during WWII. -

Uss-Sd Sd2.1

U S S S O U T H D A K O T A BATTLESHIP X Schematic Design II January 2014 Battleship South Dakota Memorial Interpretive Objectives: Concept Design Visitors will appreciate USS South Dakota’s contribution to winning the war in the Pacific 01/22/14 Visitors will discover the advances in military technology that contributed to the ship’s success Visitors will consider the various types of leadership that led to success on the ship Background Visitors will learn about Captain Gatch’s role in training and leading the ship’s first crew USS South Dakota was the first of a new class of battleships that found fame in World War II. Her keel was laid in July of 1939; she was launched in June of 1941 and was commissioned in March of 1942. While her Visitors will experience elements of life on a battleship naval career was short, the SoDak was a legend before she had even served her first year and she went on to Visitors will compare the types of weapons used on the ship become the most decorated battleship of World War II for her exploits in the Pacific. Visitors will see the impact of naval treaties on ship design and power Decommissioned in 1947, by 1962 the ship was destined for demolition. When this news reached Sioux Falls, it spawned a local effort to acquire pieces of the battleship to create a memorial. The USS South Visitors will see there was a mutually beneficial relationship between aircraft carriers and battleships Dakota Battleship Memorial opened in September of 1969 to commemorate the battleship and its hearty crew. -

Index to the Oral History of Rear Admiral Ernest M. Eller, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Index to the Oral History of Rear Admiral Ernest M. Eller, U.S. Navy (Retired) Abelson, Dr. Philip H. Work in the late 1940s in developing nuclear power for the U.S. Navy, 841, 1099- 1100 Air Force, U.S. Was an opponent of the Navy in defense unification in 1949, 853-864 Albany, USS (CA-123) Midshipman training cruise to Europe in the summer of 1951, 983-995 Deployment to the Sixth Fleet in 1951 and return home, 995-1008 Recovery of pilots from the aircraft carrier Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVB-42) in 1951, 995 In 1952 participated in cold-weather operational tests near Greenland, 1008-1014 Ship handling, 1005, 1012, 1015-1016 Training of officers and crew in 1951-52, 1014-1016 Relationship with the city of Albany, New York, 1016-1017 Albion, Dr. Robert G. Harvard professor who served from 1943 to 1950 as Assistant Director of Naval History, 1055, 1089-1090 Algeria Algiers visited by the heavy cruiser Albany (CA-123) in 1951, 1005-1006 Allard, Dr. Dean C. In the 1960s and 1970s headed the operational archives section of the Naval History Division/Naval Historical Center, 903, 1060-1061, 1070, 1101, 1111 American Ordnance Association An outgrowth of the Army Ordnance Association, it embraced the Navy shortly after World War II, 843 Anderson, Eugenie Served 1949-53 as U.S. Ambassador to Denmark, 989 Antarctica In the late 1950s Rear Admiral Richard Byrd’s family donated his Antarctica material to the Naval History Division, 1084 Antiair Warfare The training ship Utah (AG-16) participated in a war game against the Army Air Corps in 1937, 864-865 1 Antiaircraft practice by heavy cruiser Albany (CA-123) in the summer of 1951, 983, 988, 991-992 ARAMCO (Arabian American Oil Company) Role in Saudi Arabia in the early 1950s, 888, 900, 905, 931, 933-938, 944-947, 959, 962 Army Air Corps, U.S. -

Maltese Casualties in the Battle of Jutland - May 31- June 1, 1916

., ~ I\ ' ' "" ,, ~ ·r " ' •i · f.;IHJ'¥T\f 1l,.l~-!l1 MAY 26, 2019 I 55 5~ I MAY 26, 2019 THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA LIFE&WELLBEING HISTORY Maltese casualties in the Battle of Jutland - May 31- June 1, 1916 .. PATRICK FARRUGIA .... .. HMS Defence .. HMS lndefatigab!.e sinking HMS Black Prince ... In the afternoon and evening·of .. May 31, 1916, the Battle of Jutland (or Skagerrakschlact as it is krnwn •. to the Germans), was fought between the British Grand Fleet, under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the German High Seas Fleet commanded by Admiral Reinhold Scheer. It was to be the largest nava~ bat tle and the only full.-scale clash between battleships of the war. The British Grand Fleet was com posed of 151 warships, among which were 28 bat:leships and nine battle cruisers, wiile the German High Seas Fleet consisted of 99 war ships, including 16 battleships and 54 battle cruisers. Contact between these mighty fleets was made shortly after 2pm, when HMS Galatea reported that she had sighted the enemy. The first British disaster occured at 4pm, when, while engaging SMS Von der Tann, HMS Indefatigable was hit by a salvo onherupperdeck. The amidships. A huge pillar of smoke baden when they soon came under Giovanni Consiglio, Nicolo FOndac Giuseppe Cuomo and Achille the wounded men was Spiro Borg, and 5,769 men killed, among them missiles apparently penetrated her ascended to the sky, and she sank attack of the approaching battle aro, Emmanuele Ligrestischiros, Polizzi, resi1ing in Valletta, also lost son of Lorenzo and Lorenza Borg 72 men with a Malta connection; 25 'X' magazine, for she was sudcenly bow first. -

Captain John Denison, D.S.O., R.N. Oct

No. Service: Rank: Names & Service Information: Supporting Information: 27. 1st 6th Captain John Denison, D.S.O., R.N. Oct. Oct. B. 25 May 1853, Rusholine, Toronto, 7th child; 5th Son of George Taylor Denison (B. 1904 1906. Ontario, Canada. – D. 9 Mar 1939, 17 Jul 1816, Toronto, Ontario, Canada -D. 30 Mason Toronto, York, Ontario, Canada. B. May 1873, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) [Lawyer, 1 Oct 1904 North York, York County, Ontario, Colonel, General, later minister of Church) and Canada. (aged 85 years). Mary Anne Dewson (B. 24 May 1817, Enniscorthy, Ireland -D. 1900, Toronto, 1861 Census for Saint Patrick's Ontario, Canada). Married 11 Dec 1838 at St Ward, Canada West, Toronto, shows James Church. Toronto, Canada John Denison living with Denison family aged 9. Canada Issue: West>Toronto. In all they had 11 children; 8 males (sons) and 3 It is surmised that John Denison females (daughters). actually joined the Royal Navy in 18 Jul 1878 – John Denison married Florence Canada. Ledgard, B. 12 May 1857, Chapel town, 14 May 1867-18 Dec 1868 John Yorkshire, -D. 1936, Hampshire, England. Denison, aged 14 years, attached to daughter of William Ledgard (1813-1876) H.M.S. “Britannia” as a Naval Cadet. [merchant] and Catherina Brooke (1816-1886) “Britannia” was a wooden screw st at Roundhay, St John, Yorkshire, England. Three decker 1 rate ship, converted to screw whilst still on her stocks. Issue: (5 children, 3 males and 2 females). Constructed and launched from 1. John Everard Denison (B. 20 Apr 1879, Portsmouth Dockyard on 25 Jan Toronto, Ontario, Canada - D. -

The Concrete Battleship Was Flooded, the Guns Drained of Recoil Oil and Fired One Last Time, the Colors

The Iowan History letter Vol. 5 Number 2 Second Quarter, 2016 The Concrete Initially Fort Drum was planned as a mine control and mine casemate station. However, due to inadequate de- fenses in the area, a plan was devised to level the island, and then build a concrete structure on top of it armed with Battleship two twin 12-inch guns. This was submitted to the War Department, which decided to change the 12-inch guns to 14-inch guns mounted on twin armored turrets. The forward turret, with a traverse of 230°, was mounted on the forward portion of the top deck, which was 9 ft below the top deck; the rear turret, with a full 360° traverse, was mounted on the top deck. The guns of both turrets were capable of 15° elevation, giving them a range of 19,200 yards. Secondary armament was to be provided by two pairs of 6-inch guns mounted in armored casemates on either side of the main structure. There were two 3-inch mobile AA guns on “spider” mounts for anti-aircraft de- fense. Fort Drum in the 1930s Overhead protection of the fort was provided by an 20- Fort Drum (El Fraile Island), also known as “the con- foot thick steel-reinforced concrete deck. Its exterior walls crete battleship,” is a heavily fortified island situated at ranged between approximately 25 to 36 ft thick, making it the mouth of Manila Bay in the Philippines, due south of virtually impregnable to enemy naval attack. Corregidor Island. The reinforced concrete fortress shaped like a battleship, was built by the United States in 1909 as Construction one of the harbor defenses at the wider South Channel entrance to the bay during the American colonial period. -

Fear God and Dread Nought: Naval Arms Control and Counterfactual Diplomacy Before the Great War

FEAR GOD AND DREAD NOUGHT: NAVAL ARMS CONTROL AND COUNTERFACTUAL DIPLOMACY BEFORE THE GREAT WAR James Kraska* bqxz.saRJTANwu JIALAPROP! ">0 0 FWS 7-4 INDOOA.t FI. R- = r---------------------------------------------------------------------- MRS. BRITANNIA MALAPROP In the years preceding the First World War, Britain and Germany were engaged in a classic arms spiral, pursuing naval fleet expansion programs directed against each other. Mrs. BritanniaMalaprop, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 24, 1912, at 16. * International law attorney with the U.S. Navy currently assigned to The Joint Staff in the Pentagon. L.L.M., The University of Virginia (2005) and Guest Investigator, Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Mass. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Defense or any of its components. 44 GA. J. INT'L & COMP. L. [Vol. 34:43 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................... 45 II. THE INTERDISCIPLINARY NATURE OF INQUIRY INTO DIPLOMACY ... 47 A. Realism and Liberalism as Guides in Diplomacy ............. 47 B. Diplomacy and the First Image .......................... 50 C. CounterfactualAnalysis in InternationalLaw and D iplomacy ........................................... 52 1. CounterfactualMethodology .......................... 57 2. Criticism of CounterfactualAnalysis ................... 60 III. ANGLO-GERMAN NAVAL DIPLOMACY BEFORE THE GREAT WAR ... 62 A. Geo-strategicPolitics .................................. 64 1. DreadnoughtBattleships -

Full Spring 2004 Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Article 1 Number 2 Spring 2004 Full Spring 2004 Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2004) "Full Spring 2004 Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Full Spring 2004 Issue N A V A L W A R C O L L E G E NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW R E V I E W Spring 2004 Volume LVII, Number 2 Spring 2004 Spring N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O N L L U E E G H E T R I VI IBU OR A S CT MARI VI Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2004 1 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Naval War College Review, Vol. 57 [2004], No. 2, Art. 1 Cover A Landsat-7 image (taken on 27 July 2000) of the Lena Delta on the Russian Arctic coast, where the Lena River emp- ties into the Laptev Sea. The Lena, which flows northward some 2,800 miles through Siberia, is one of the largest rivers in the world; the delta is a pro- tected wilderness area, the largest in Rus- sia.