Comanagement:An Alternative Model for Governance of Gairan(Grazing Land) in Maharashtra :A Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Implementation of the DI-LRMP in the State of Maharashtra a Study by the Finance Research Group, Indira Gandhi

Report on the Implementation of the DI-LRMP in the State of Maharashtra A study by the Finance Research Group, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Report on the implementation of the Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP) in the state of Maharashtra Finance Research Group, Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Team: Prof. Sudha Narayanan Gausia Shaikh Diya Uday Bhargavi Zaveri 2nd November, 2017 Contents 1 Executive Summary . 5 2 Acknowledgements . 13 3 Introduction . 15 I State level assessment 19 4 Land administration in Maharashtra . 21 5 Digitalisation initiatives in Maharashtra . 47 6 DILRMP implementation in Maharashtra . 53 II Tehsil and parcel level assessment 71 7 Mulshi, Palghar and the parcels . 73 8 Methodology for ground level assessments . 79 9 Tehsil-level findings . 83 10 Findings at the parcel level . 97 4 III Conclusion 109 11 Problems and recommendations . 111 A estionnaire and responses . 117 B Laws governing land-related maers in Maharashtra . 151 C List of notified public services . 155 1 — Executive Summary The objectives of land record modernisation are two-fold. Firstly, to clarify property rights, by ensuring that land records maintained by the State mirror the reality on the ground. A discordance between the two, i.e., records and reality, implies that it is dicult to ascertain and assert rights over land. Secondly, land record modernisation aims to reduce the costs involved for the citizen to access and correct records easily in order to ensure that the records are updated in a timely manner. This report aims to map, on a pilot basis, the progress of the DILRMP, a Centrally Sponsored Scheme, in the State of Maharashtra. -

City Development Plan Pune Cantonment Board Jnnurm

City Development Plan Pune Cantonment Board JnNURM DRAFT REPORT, NOVEMBER 2013 CREATIONS ENGINEER’S PRIVATE LIMITED City Development Plan – Pune Cantonment Board JnNURM Abbreviations WORDS ARV Annual Rental Value CDP City Development Plan CEO Chief Executive Officer CIP City Investment Plan CPHEEO Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation FOP Financial Operating Plan JNNURM Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission KDMC Kalyan‐Dombivali Municipal Corporation LBT Local Body Tax MoUD Ministry of Urban Development MSW Municipal Solid Waste O&M Operation and Maintenance PCB Pune Cantonment Board PCMC Pimpri‐Chinchwad Municipal Corporation PCNTDA Pimpri‐Chinchwad New Town Development Authority PMC Pune Municipal Corporation PMPML Pune MahanagarParivahanMahamandal Limited PPP Public Private Partnership SLB Service Level Benchmarks STP Sewerage Treatment Plant SWM Solid Waste Management WTP Water Treatment Plant UNITS 2 Draft Final Report City Development Plan – Pune Cantonment Board JnNURM Km Kilometer KW Kilo Watt LPCD Liter Per Capita Per Day M Meter MM Millimeter MLD Million Litres Per Day Rmt Running Meter Rs Rupees Sq. Km Square Kilometer Tn Tonne 3 Draft Final Report City Development Plan – Pune Cantonment Board JnNURM Contents ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................................... -

By Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Doctor of Philosophy) Faculty for Moral and Social Sciences Department Of

“A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES PUNE DISTRICTS, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA” BY Dr. PRATAPRAO RAMGHANDRA DIGHAVKAR, I. P. S. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF VIDYAVACHASPATI (DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY) FACULTY FOR MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDHYAPEETH PUNE JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the entire work embodied in this thesis entitled A STUDY OFECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRILISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES .PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013-2015 has been carried out by the candidate DR.PRATAPRAO RAMCHANDRA DIGHAVKAR. I. P. S. under my supervision/guidance in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such materials as has been obtained by other sources and has been duly acknowledged in the thesis have not been submitted to any degree or diploma of any University or Institution previously. Date: / / 2016 Place: Pune. Dr.Prataprao Ramchatra Dighavkar, I.P.S. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISNTION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES ,PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013—2015 is written and submitted by me at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The present research work is of original nature and the conclusions are base on the data collected by me. To the best of my knowledge this piece of work has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any University or Institution. -

Bpc(Maharashtra) (Times of India).Xlsx

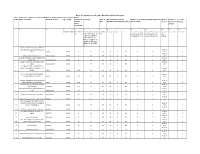

Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships BPCL proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Maharashtra as per following details : Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be arranged by the applicant Mode of Fixed Fee / Security monthly Site* M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. M.). * (Rs in Lakhs) Selection Minimum Bid Deposit Sales amount Potential # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular / Rural MS+HSD in SC/ SC CC1/ SC CC- CC/DC/C Frontage Depth Area Estimated working Estimated fund required Draw of Rs in Lakhs Rs in Lakhs Kls 2/ SC PH/ ST/ ST CC- FS capital requirement for development of Lots / 1/ ST CC-2/ ST PH/ for operation of RO infrastructure at RO Bidding OBC/ OBC CC-1/ OBC CC-2/ OBC PH/ OPEN/ OPEN CC-1/ OPEN CC-2/ OPEN PH From Aastha Hospital to Jalna APMC on New Mondha road, within Municipal Draw of 1 Limits JALNA RURAL 33 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 2 VIllage jamgaon taluka parner AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE KOMBHALI,TALUKA KARJAT(NOT Draw of 3 ON NH/SH) AHMEDNAGAR RURAL 25 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Ambhai, Tal - Sillod Other than Draw of 4 NH/SH AURANGABAD RURAL 25 ST CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON MAHALUNGE - NANDE ROAD, MAHALUNGE GRAM PANCHYAT, TAL: Draw of 5 MULSHI PUNE RURAL 300 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 ON 1.1 NEW DP ROAD (30 M WIDE), Draw of 6 VILLAGE: DEHU, TAL: HAVELI PUNE RURAL 140 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 VILLAGE- RAJEGAON, TALUKA: DAUND Draw of 7 ON BHIGWAN-MALTHAN -

EIA: India: Pune Nirvana Hills Slum Rehabilitation Project

Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report and Environment and Social Management Plan Project Number: 44940 March 2012 IND: Pune Nirvana Hills Slum Rehabilitation Project Prepared by: Kumar Urban Development Limited This report is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for Project Nirvana: Pune, India Kumar Sinew Developers Private Final Report Limited March 2012 www.erm.com Delivering sustainable solutions in a more competitive world FINAL REPORT Kumar Sinew Developers Private Limited Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for Project Nirvana: Pune, India 23 March 2012 Reference : I8390 / 0138632 Rutuja Tendolkar Prepared by: Consultant Reviewed & Neena Singh Approved by: Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ERM India Private Limited has been engaged by M/s Kumar Sinew Urban Developers Limited (hereinafter referred to as ‘KUL’ or ‘the client’) on the behest of the Asian Development Bank (ADB), to update the Environmental Impact Assessment report of the “Nirvana Hills Phase II” Project (hereinafter referred to as ‘Project Nirvana’) located at Survey No. -

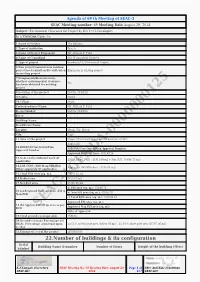

SELF STUDY REPORT for 3Rd CYCLE of ACCREDITATION

SELF STUDY REPORT FOR 3rd CYCLE OF ACCREDITATION EKMEKA SAHAYA KARU/AWAGHE DHARU SUPANTH AMBEGAON TALUKA VIDYA VIKAS MANDAL,S B.D KALE MAHAVIDYALAYA B.D.KALE MAHAVIDYALAYA,GHODEGAON,TAL-AMBEGAON,DIST- PUNE,STATE-MAHARASHTRA,PIN-412408 412408 www.bdkalecollege.in SSR SUBMITTED DATE: 26-02-2018 Submitted To NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL BANGALORE February 2018 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 INTRODUCTION Ambegaon TalukaVidya Vikas Mandal was established in 1954 at Ghodegaon, Tal-Ambegaon, Dist-Pune in Maharashtra state, with a vision and mission to impart education to the children of downtrodden and deprived sections of the society. Our institution tried to transform the lifestyle and standard of living of the society by providing education. Our management has been following the footsteps of great social reformers like Mahatma Phule, Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar, and Bhaurav Patil who rendered noble services for the educational development of the weaker section of society. Our institution established educational sister institutes covering the large area of tribal villages. At present, our institution runs the following branches: 1. Janata Vidya Mandir and Junior college with MCVC, Ghodegaon 2. Extension Branch of Janata vidya Mandir sal 3. Muktai Prashala, Pimpalgaon 4. New English School, Ghodegaon 5. B.D Kale Mahavidyalaya,Ghodegaon 6. Janata Boy’s Hostel, Ghodegaon B. D Kale Mahavidyalaya was established in 1989, affiliating to the University of Pune. After taking into account the need for commerce education, the commerce faculty was started in 1989 and Arts faculty in 1991. To meet the need of parents and students, the college started arts faculty and then P.G courses: M.A.(Marathi) and M.Com. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

Table of Contents ABOUT KALPAVRIKSH 1 Beginnings 1 Philosophy 1 Governance 1 Functioning 1 Annual General Body Meeting 1 Committee for Prevention Of Sexual Harassment 2 Kalpavriksh’s 40 year Journey- A brief overview 3 PART A: PROJECTS/ACTIVITIES/CAMPAIGNS 5 A1 Environment Education 5 A1.1 Development, promotion, marketing of Children’s Books 5 A1.2 Ladakh Food Book 5 A1.3 Miscellaneous 6 A2 Conservation and Livelihoods 8 A2.1 Community Conserved Areas 8 A2.2 Continued Research and Advocacy on the Forest Rights Act 9 A2.3 Democratising Conservation Governance 10 A2.4 Documentation and Outreach Service in Community Based Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Security 11 A2.5 Intervention, Documentation and Outreach towards Community Based Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Security in and around Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary 12 A2.6 Biodiversity Assessment and Conservation Priority Plan of Sahyadri School Campus 13 A2.7 P.A. Update 14 A3 Environment and Development 16 A3.1 Rivers, Dams and environmental governance in Northeast India 16 A3.2 Andaman & Nicobar Islands e-group 16 A4 Alternatives 17 A4.1 Activities in / relating to India 17 A4.1.1 Alternatives Confluences of Youth for Ecological Sustainability 17 A4.1.2 Documentation and Outreach Centre For Community Based Biodiversity Conservation and Livelihood Security 20 A4.1.3 Agro-ecology case-study on millet revival 21 A4.1.4 Alternative Practices and Visions in India: Documentation, Networking, and Advocacy 22 A4.2 Global Activities 29 A4.2.1 Academic-Activist -

0 0 23 Feb 2021 152000417

Annexure I Annexure II ' .!'r ' .tu." "ffi* Government of Maharashtra, Directorate of Geology and Mining, "Khanij Bhavan",27, Shivaji Nagar, Cement Road, Nagpur-,1.10010 CERTIFICATE This is hereby certified that the mining lease granted to ]Ws Minerals & Metals over an area 27.45.20 Hec. situated in village Redi, Taluka Vengurla, District- Sindhudurg has no production of mineral since its originally lease deed execution. This certificate is issued on the basis of data provided by the District Collectorate, Sindhudurg. Mr*t, Place - Nagpur Director, Date - l1109/2020 Directorate of Geology and Mining, Government of Maharashtra, Nagpur 'ffi & r6nrr arn;r \k{rc sTrnrr qfrT6{ rtqailEc, ttufrg Qs, rr+at', fula rl-c, ffi qm, - YXo oqo ({lrr{ fF. osRe-?eao\e\\ t-m f. oeit-tlqqeqr f-+d , [email protected], [email protected]!.in *-.(rffi rw+m-12,S-s{r.r- x/?ol./ 26 5 5 flfii6- tocteo?o yfr, ll lsepzolo ifuflRirrs+ew, I J 1r.3TrvfdNfu{-{r rrs. \ffi-xooolq fus-q ti.H m.ffi, tu.frgq,l ffi ql* 1s.yr t ffiTq sF<-qrartq-qrsrufl -srd-d.. vs1{ cl fu€I EFro.{ srfffi, feqi,t fi q* fr.qo7o1,7qoqo. rl enqd qx fl<ato lq/os/?o?o Bq-tn Bqqri' gr{d,rr+ f frflw oTu-s +.€, r}.t* ar.ffi, fii.fufli ++d sll tir.xq t E'fr-qrqr T6 c$ Efurqgr tTer<ir+ RctsTcr{r :-err+ grd ;RrerrqTEkT squrq-d qT€t{d df,r{ +'t"qra *a eG. Tr6qrl :- irftf,fclo} In@r- t qr.{qrroi* qrqi;dqrf,q I fc.vfi.firqr|. -

S.No. Commissioner of Central Excise Jurisdiction

The Districts of Panchmahal and Dahod, and the following areas of District of Vadodara :- (a) Waghodia Taluka, (b) Area of Karjan Taluka and Vadodara Taluka bound by Vadodara-Mumbai railway line on the west, on the east by the boundaries of Karjan Taluka and 23 Vadodara Taluka, on the north by Jambuva river, on the south by the Vadodara-II boundary of Vadodara District, and (c) Area of Vadodara Taluka bound on the west by Mumbai-Vadodara railway line, on the north by GIDC (Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation) Ring Road from Vadsar overbridge to Sussen crossroads, on the south by Jambuva river, and on the east by old National Highway No.8. In the Districts of Srikakulam, Vizianagaram and Visakhapatnam excluding the mandals of Nakkapalli, Sarvasidhi Rayavaram, Yelamanchili, Rambilli, Kasimkota, Atchutapuram, Paravada, Anakapalli, Chodavaram, Cheedikada, Hukumpeta, Butchayyapeta, Kotauratla, Makavarapalem, Ravikamatham, Madugula, Paderu, Visakhapatnam Pedabayalu, Munchingiputtu, Gangaraju Madugula, Chintapalle, 24 ( Visakhapatnam-I) Gudem Kothaveedhi, Payakaraopeta, Koyyuru, Roluguntla, Narsipatnam, Nathavaram, Pedagantyada, Munagapaka, Sabbavaram, Golugunta and Gajuwaka mandal but including the villages/ Areas of Thunglam and the entire area falling under Autonagar Industrial Area, Akkareddipalem, Mindi, Nathayyapalem, Dolphin’s Nose and Yarada of Gajuwaka mandal in the State of Andhra Pradesh. 25 Large Taxpayer Unit Throughout the territory of India TableIII(B) S.No. Commissioner of Jurisdiction Central Excise (1) (2) (3) Districts of Agra, Ferozabad, Hathras, Mathura, Aligarh, Auraiya, 1 Agra Etawah, Farrukhabad, Kannauj, Mainpuri, Etah and Kasganj of the State of Uttar Pradesh . Area on the eastern side of Sabarmati river starting from Nehru Bridge towards northern side of Relief Road extending upto Kalupur. -

Environmental Clearance Yes Has Been Obtained for Existing Project 8.Location of the Project Gat No

Agenda of 69 th Meeting of SEAC-3 SEAC Meeting number: 69 Meeting Date August 29, 2018 Subject: Environment Clearance for Project by M/s S.O.L Developers Is a Violation Case: No 1.Name of Project The Address 2.Type of institution Private 3.Name of Project Proponent Mr. Mukesh P. Patel 4.Name of Consultant M/s JV Analytical Services 5.Type of project Residential & Commercial Project 6.New project/expansion in existing project/modernization/diversification Expansion in existing project in existing project 7.If expansion/diversification, whether environmental clearance Yes has been obtained for existing project 8.Location of the project Gat No. 519/520, 9.Taluka Haveli 10.Village Moshi Correspondence Name: Mr. Mukesh P. Patel Room Number: Gat No. 519/520, Floor: - Building Name: - Road/Street Name: - Locality: Moshi, Tal. Haveli City: Pune 11.Area of the project Pimpri Chinchwad Municipal Corporation (PCMC) Applicable 12.IOD/IOA/Concession/Plan IOD/IOA/Concession/Plan Approval Number: - Approval Number Approved Built-up Area: 100199.24 13.Note on the initiated work (If 22608.19 m2 ( FSI : 11911.44 m2 + Non-FSI : 10696.75 m2) applicable) 14.LOI / NOC / IOD from MHADA/ Applicable (MHADA Area : 5495.85 m2) Other approvals (If applicable) 15.Total Plot Area (sq. m.) 39381.05 m2 16.Deductions 3615.09 m2 17.Net Plot area 35765.96 m2 a) FSI area (sq. m.): 53190.74 18 (a).Proposed Built-up Area (FSI & b) Non FSI area (sq. m.): 47008.50 Non-FSI) c) Total BUA area (sq. m.): 100199.24 Approved FSI area (sq. -

A Study of Basic Amenities in Tribal Area of Ambegaon Taluka with Special Reference to Electricity and Telecommunication

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 A Study of Basic Amenities in Tribal Area of Ambegaon Taluka with Special Reference to Electricity and Telecommunication Prof. Mayur Chikhale*1, Assistant Professor, Adhalraon Patil Institute of Management and Research, Landewadi, Manchar, Pune | Email- [email protected] Dr. Dhananjay Pingale, PhD Associate Professor, Adhalraon Patil Institute of Management and Research, Landewadi, Manchar, Pune | Email- [email protected] Abstract Ambegaon Tehsil is classified as tribal area in Pune District and having 23 per cent of land covered the forest, providing home to Hindu Mahadev Koli peoples (tribal) in the vicinity. The present study put its efforts on understanding the level of basic amenities provided to these tribal peoples in terms of transportation, drinkable water and telecommunication facility. The paper studied 15 villages of Ambegaon Tehsil and investigated opinions of 51 tribal peoples. Ultimately, it has observed that, transport facility is not sufficiently provided and arrangement of alternate energy source for cooking needs to be provided. These are the post research policy suggestions given based on the investigation made in this research study. Keywords: Basic Amenities, Rural Area of Ambegaon Tehsil, Electricity and Telecommunication Introduction It is highly observed that the urban area peoples and rural area peoples have very differential lifestyles as well as their problems. This has reflected in considering the present research for understanding on the pain areas for suffering a lot in regards with the basic needs of the rural life. The present study focuses on basic amenities or may be called as basic needs for 21st century citizens, namely, (a) transportation facility available in the vicinity, (b) market accessibility from the residential place, (c) drinkable water facility, and (d) telecommunication facility available. -

Study of Landslide Hazard Zonation Using Remote Sensing and GIS

CIKITUSI JOURNAL FOR MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH ISSN NO: 0975-6876 Study of Landslide Hazard Zonation Using Remote Sensing and GIS Technique for Ambegaon Taluka of Pune District ,Maharashtra Mujawar K C, Patil Supraja, Mohite Onkar, Shinde Sachin, Sathe Shailesh, Mhetre Audumbar, Karkar Madhura, Chavan Ashwin Department of civil Engineering, N B Navale Sinhga, d College of Engineering,Kegaon,Solapur Email:[email protected] Abstract Landslide is naturally defined by a large range of ground movement, such as rock falls, deep failure of slopes, and shallow debris flows. Landslide hazard results in great loss of life and property. These damages can be avoided if the cause and effect relationships of the events are known. As long as landslides occur in remote, unpopulated regions, they are treated as just another denudation process sculpting the landscape, but when occur in populated regions; they become subjects of serious study. The study area Ambegaon taluka is a part of the Pune District located between 18° 50 N and 19° 20’N latitude and between 73°25 E and 74°15E longitude. The study area falls in the Survey of India Toposheets 47E/12, 47E/16, 47I/4, 47F/9, 47F/13 in 1:50,000 scale. It covers an area 987sq.km.The present work is an attempt towards application of GIS for landslide vulnerability mapping. Different thematic layers have been prepared such as geomorphology, lineament density, drainage density, slope, soil depth, and land use. The numerical weights of the categories of the factors have been determined using subject knowledge. The present study based on spatial analysis of the ambegaon taluka drainage basin using Satellite data along with the field data in a GIS Environment.