A Clasification of Known Root Prime-Generating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fast Tabulation of Challenge Pseudoprimes Andrew Shallue and Jonathan Webster

THE OPEN BOOK SERIES 2 ANTS XIII Proceedings of the Thirteenth Algorithmic Number Theory Symposium Fast tabulation of challenge pseudoprimes Andrew Shallue and Jonathan Webster msp THE OPEN BOOK SERIES 2 (2019) Thirteenth Algorithmic Number Theory Symposium msp dx.doi.org/10.2140/obs.2019.2.411 Fast tabulation of challenge pseudoprimes Andrew Shallue and Jonathan Webster We provide a new algorithm for tabulating composite numbers which are pseudoprimes to both a Fermat test and a Lucas test. Our algorithm is optimized for parameter choices that minimize the occurrence of pseudoprimes, and for pseudoprimes with a fixed number of prime factors. Using this, we have confirmed that there are no PSW-challenge pseudoprimes with two or three prime factors up to 280. In the case where one is tabulating challenge pseudoprimes with a fixed number of prime factors, we prove our algorithm gives an unconditional asymptotic improvement over previous methods. 1. Introduction Pomerance, Selfridge, and Wagstaff famously offered $620 for a composite n that satisfies (1) 2n 1 1 .mod n/ so n is a base-2 Fermat pseudoprime, Á (2) .5 n/ 1 so n is not a square modulo 5, and j D (3) Fn 1 0 .mod n/ so n is a Fibonacci pseudoprime, C Á or to prove that no such n exists. We call composites that satisfy these conditions PSW-challenge pseudo- primes. In[PSW80] they credit R. Baillie with the discovery that combining a Fermat test with a Lucas test (with a certain specific parameter choice) makes for an especially effective primality test[BW80]. -

FACTORING COMPOSITES TESTING PRIMES Amin Witno

WON Series in Discrete Mathematics and Modern Algebra Volume 3 FACTORING COMPOSITES TESTING PRIMES Amin Witno Preface These notes were used for the lectures in Math 472 (Computational Number Theory) at Philadelphia University, Jordan.1 The module was aborted in 2012, and since then this last edition has been preserved and updated only for minor corrections. Outline notes are more like a revision. No student is expected to fully benefit from these notes unless they have regularly attended the lectures. 1 The RSA Cryptosystem Sensitive messages, when transferred over the internet, need to be encrypted, i.e., changed into a secret code in such a way that only the intended receiver who has the secret key is able to read it. It is common that alphabetical characters are converted to their numerical ASCII equivalents before they are encrypted, hence the coded message will look like integer strings. The RSA algorithm is an encryption-decryption process which is widely employed today. In practice, the encryption key can be made public, and doing so will not risk the security of the system. This feature is a characteristic of the so-called public-key cryptosystem. Ali selects two distinct primes p and q which are very large, over a hundred digits each. He computes n = pq, ϕ = (p − 1)(q − 1), and determines a rather small number e which will serve as the encryption key, making sure that e has no common factor with ϕ. He then chooses another integer d < n satisfying de % ϕ = 1; This d is his decryption key. When all is ready, Ali gives to Beth the pair (n; e) and keeps the rest secret. -

The Pseudoprimes to 25 • 109

MATHEMATICS OF COMPUTATION, VOLUME 35, NUMBER 151 JULY 1980, PAGES 1003-1026 The Pseudoprimes to 25 • 109 By Carl Pomerance, J. L. Selfridge and Samuel S. Wagstaff, Jr. Abstract. The odd composite n < 25 • 10 such that 2n_1 = 1 (mod n) have been determined and their distribution tabulated. We investigate the properties of three special types of pseudoprimes: Euler pseudoprimes, strong pseudoprimes, and Car- michael numbers. The theoretical upper bound and the heuristic lower bound due to Erdös for the counting function of the Carmichael numbers are both sharpened. Several new quick tests for primality are proposed, including some which combine pseudoprimes with Lucas sequences. 1. Introduction. According to Fermat's "Little Theorem", if p is prime and (a, p) = 1, then ap~1 = 1 (mod p). This theorem provides a "test" for primality which is very often correct: Given a large odd integer p, choose some a satisfying 1 <a <p - 1 and compute ap~1 (mod p). If ap~1 pi (mod p), then p is certainly composite. If ap~l = 1 (mod p), then p is probably prime. Odd composite numbers n for which (1) a"_1 = l (mod«) are called pseudoprimes to base a (psp(a)). (For simplicity, a can be any positive in- teger in this definition. We could let a be negative with little additional work. In the last 15 years, some authors have used pseudoprime (base a) to mean any number n > 1 satisfying (1), whether composite or prime.) It is well known that for each base a, there are infinitely many pseudoprimes to base a. -

Sequences of Primes Obtained by the Method of Concatenation

SEQUENCES OF PRIMES OBTAINED BY THE METHOD OF CONCATENATION (COLLECTED PAPERS) Copyright 2016 by Marius Coman Education Publishing 1313 Chesapeake Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43212 USA Tel. (614) 485-0721 Peer-Reviewers: Dr. A. A. Salama, Faculty of Science, Port Said University, Egypt. Said Broumi, Univ. of Hassan II Mohammedia, Casablanca, Morocco. Pabitra Kumar Maji, Math Department, K. N. University, WB, India. S. A. Albolwi, King Abdulaziz Univ., Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Mohamed Eisa, Dept. of Computer Science, Port Said Univ., Egypt. EAN: 9781599734668 ISBN: 978-1-59973-466-8 1 INTRODUCTION The definition of “concatenation” in mathematics is, according to Wikipedia, “the joining of two numbers by their numerals. That is, the concatenation of 69 and 420 is 69420”. Though the method of concatenation is widely considered as a part of so called “recreational mathematics”, in fact this method can often lead to very “serious” results, and even more than that, to really amazing results. This is the purpose of this book: to show that this method, unfairly neglected, can be a powerful tool in number theory. In particular, as revealed by the title, I used the method of concatenation in this book to obtain possible infinite sequences of primes. Part One of this book, “Primes in Smarandache concatenated sequences and Smarandache-Coman sequences”, contains 12 papers on various sequences of primes that are distinguished among the terms of the well known Smarandache concatenated sequences (as, for instance, the prime terms in Smarandache concatenated odd -

Conjecture of Twin Primes (Still Unsolved Problem in Number Theory) an Expository Essay

Surveys in Mathematics and its Applications ISSN 1842-6298 (electronic), 1843-7265 (print) Volume 12 (2017), 229 { 252 CONJECTURE OF TWIN PRIMES (STILL UNSOLVED PROBLEM IN NUMBER THEORY) AN EXPOSITORY ESSAY Hayat Rezgui Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to gather as much results of advances, recent and previous works as possible concerning the oldest outstanding still unsolved problem in Number Theory (and the most elusive open problem in prime numbers) called "Twin primes conjecture" (8th problem of David Hilbert, stated in 1900) which has eluded many gifted mathematicians. This conjecture has been circulating for decades, even with the progress of contemporary technology that puts the whole world within our reach. So, simple to state, yet so hard to prove. Basic Concepts, many and varied topics regarding the Twin prime conjecture will be cover. Petronas towers (Twin towers) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification: 11A41; 97Fxx; 11Yxx. Keywords: Twin primes; Brun's constant; Zhang's discovery; Polymath project. ****************************************************************************** http://www.utgjiu.ro/math/sma 230 H. Rezgui Contents 1 Introduction 230 2 History and some interesting deep results 231 2.1 Yitang Zhang's discovery (April 17, 2013)............... 236 2.2 "Polymath project"........................... 236 2.2.1 Computational successes (June 4, July 27, 2013)....... 237 2.2.2 Spectacular progress (November 19, 2013)........... 237 3 Some of largest (titanic & gigantic) known twin primes 238 4 Properties 240 5 First twin primes less than 3002 241 6 Rarefaction of twin prime numbers 244 7 Conclusion 246 1 Introduction The prime numbers's study is the foundation and basic part of the oldest branches of mathematics so called "Arithmetic" which supposes the establishment of theorems. -

1 Abelian Group 266 Absolute Value 307 Addition Mod P 427 Additive

1 abelian group 266 certificate authority 280 absolute value 307 certificate of primality 405 addition mod P 427 characteristic equation 341, 347 additive identity 293, 497 characteristic of field 313 additive inverse 293 cheating xvi, 279, 280 adjoin root 425, 469 Chebycheff’s inequality 93 Advanced Encryption Standard Chebycheff’s theorem 193 (AES) 100, 106, 159 Chinese Remainder Theorem 214 affine cipher 13 chosen-plaintext attack xviii, 4, 14, algorithm xix, 150 141, 178 anagram 43, 98 cipher xvii Arithmetica key exchange 183 ciphertext xvii, 2 Artin group 185 ciphertext-only attack xviii, 4, 14, 142 ASCII xix classic block interleaver 56 asymmetric cipher xviii, 160 classical cipher xviii asynchronous cipher 99 code xvii Atlantic City algorithm 153 code-book attack 105 attack xviii common divisor 110 authentication 189, 288 common modulus attack 169 common multiple 110 baby-step giant-step 432 common words 32 Bell’s theorem 187 complex analysis 452 bijective 14, 486 complexity 149 binary search 489 composite function 487 binomial coefficient 19, 90, 200 compositeness test 264 birthday paradox 28, 389 composition of permutations 48 bit operation 149 compression permutation 102 block chaining 105 conditional probability 27 block cipher 98, 139 confusion 99, 101 block interleaver 56 congruence 130, 216 Blum integer 164 congruence class 130, 424 Blum–Blum–Shub generator 337 congruential generator 333 braid group 184 conjugacy problem 184 broadcast attack 170 contact method 44 brute force attack 3, 14 convolution product 237 bubble sort 490 coprime -

On Types of Elliptic Pseudoprimes

journal of Groups, Complexity, Cryptology Volume 13, Issue 1, 2021, pp. 1:1–1:33 Submitted Jan. 07, 2019 https://gcc.episciences.org/ Published Feb. 09, 2021 ON TYPES OF ELLIPTIC PSEUDOPRIMES LILJANA BABINKOSTOVA, A. HERNANDEZ-ESPIET,´ AND H. Y. KIM Boise State University e-mail address: [email protected] Rutgers University e-mail address: [email protected] University of Wisconsin-Madison e-mail address: [email protected] Abstract. We generalize Silverman's [31] notions of elliptic pseudoprimes and elliptic Carmichael numbers to analogues of Euler-Jacobi and strong pseudoprimes. We inspect the relationships among Euler elliptic Carmichael numbers, strong elliptic Carmichael numbers, products of anomalous primes and elliptic Korselt numbers of Type I, the former two of which we introduce and the latter two of which were introduced by Mazur [21] and Silverman [31] respectively. In particular, we expand upon the work of Babinkostova et al. [3] on the density of certain elliptic Korselt numbers of Type I which are products of anomalous primes, proving a conjecture stated in [3]. 1. Introduction The problem of efficiently distinguishing the prime numbers from the composite numbers has been a fundamental problem for a long time. One of the first primality tests in modern number theory came from Fermat Little Theorem: if p is a prime number and a is an integer not divisible by p, then ap−1 ≡ 1 (mod p). The original notion of a pseudoprime (sometimes called a Fermat pseudoprime) involves counterexamples to the converse of this theorem. A pseudoprime to the base a is a composite number N such aN−1 ≡ 1 mod N. -

Number Theory Boring? Nein!

Running head: PATTERNS IN NINE 1 Number Theory Boring? Nein! Discerning Patterns in Multiples of Nine Gina Higgins Mathematical Evolutions Jenny McCarthy, Jonathan Phillips Summer Ventures in Science and Mathematics The University of North Carolina at Charlotte PATTERNS IN NINE 2 Abstract This is the process Gina Higgins went through in order to prove that the digital sum of a whole, natural number multiplied by nine would always equal nine. This paper gives a brief history on the number nine and gives a color coded, three-hundred row chart of multiplies of nine as an example and reference. Basic number theory principles were applied with Mathematical Implementation to successfully create a method that confirmed the hypothesis that the digital root of every product of nine equals nine. From this method could evolve into possible future attempts to prove why the digital root anomaly occurred. PATTERNS IN NINE 3 The number nine is the largest digit in a based ten number (decimal) system. In many ancient cultures such as China, India and Egypt, the number nine was a symbol of strength representing royalty, religion or powerful enemies (Mackenzie, 2005). The symbol for the number nine used most commonly today developed from the Hindu-Arabic System written in the third century. Those symbols developed from the Brahmi numerals found as far back as 300 BC. (Ifrah, 1981) Figure 1 Number theory is a branch of mathematics dealing specifically with patterns and sequences found in whole numbers. It was long considered the purest form of mathematics because there was not a practical application until the 20th century when the computer was invented. -

Fast Tabulation of Challenge Pseudoprimes

Fast Tabulation of Challenge Pseudoprimes Andrew Shallue Jonathan Webster Illinois Wesleyan University Butler University ANTS-XIII, 2018 1 / 18 Outline Elementary theorems and definitions Challenge pseudoprime Algorithmic theory Sketch of analysis Future work 2 / 18 Definition If n is a composite integer with gcd(b, n) = 1 and bn−1 ≡ 1 (mod n) then we call n a base b Fermat pseudoprime. Fermat’s Little Theorem Theorem If p is prime and gcd(b, p) = 1 then bp−1 ≡ 1 (mod p). 3 / 18 Fermat’s Little Theorem Theorem If p is prime and gcd(b, p) = 1 then bp−1 ≡ 1 (mod p). Definition If n is a composite integer with gcd(b, n) = 1 and bn−1 ≡ 1 (mod n) then we call n a base b Fermat pseudoprime. 3 / 18 Lucas Sequences Definition Let P, Q be integers, and let D = P2 − 4Q (called the discriminant). Let α and β be the two roots of x 2 − Px + Q. Then we have an integer sequence Uk defined by αk − βk U = k α − β called the (P, Q)-Lucas sequence. Definition Equivalently, we may define this as a recurrence relation: U0 = 0, U1 = 1, and Un = PUn−1 − QUn−2. 4 / 18 Definition If n is a composite integer with gcd(n, 2QD) = 1 such that Un−(n) ≡ 0 (mod n) then we call n a (P, Q)-Lucas pseudoprime. An Analogous Theorem Theorem Let the (P, Q)-Lucas sequence be given, and let (n) = (D|n) be the Jacobi symbol. If p is an odd prime and gcd(p, 2QD) = 1, then Up−(p) ≡ 0 (mod p) 5 / 18 An Analogous Theorem Theorem Let the (P, Q)-Lucas sequence be given, and let (n) = (D|n) be the Jacobi symbol. -

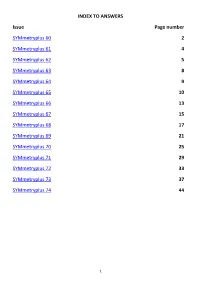

INDEX to ANSWERS Issue Page Number Symmetryplus 60 2

INDEX TO ANSWERS Issue Page number SYMmetryplus 60 2 SYMmetryplus 61 4 SYMmetryplus 62 5 SYMmetryplus 63 8 SYMmetryplus 64 9 SYMmetryplus 65 10 SYMmetryplus 66 13 SYMmetryplus 67 15 SYMmetryplus 68 17 SYMmetryplus 69 21 SYMmetryplus 70 25 SYMmetryplus 71 29 SYMmetryplus 72 33 SYMmetryplus 73 37 SYMmetryplus 74 44 1 ANSWERS FROM ISSUE 60 SOME TRIANGLE NUMBERS – 2 Many thanks to Andrew Palfreyman who found five, not four solutions! 7 7 7 7 7 1 0 5 3 0 0 4 0 6 9 0 3 9 4 6 3 3 3 3 1 Grid A 6 6 1 3 2 6 2 0 1 6 0 0 Grid B CROSSNUMBER Many thanks again to Andrew Palfreyman who pointed out that 1 Down and 8 Across do not give unique answers so there are four possible solutions. 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 4 4 8 1 4 4 8 1 4 4 8 1 4 4 8 3 3 3 3 3 9 1 9 8 9 1 9 3 9 1 9 8 9 1 9 4 5 4 5 4 5 4 5 2 3 1 0 2 3 1 0 2 3 1 0 2 3 1 0 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 1 0 9 8 1 0 9 8 1 0 9 8 1 0 9 8 8 9 8 9 8 9 8 9 3 6 1 0 3 6 1 0 9 6 1 0 9 6 1 0 10 10 10 10 5 3 4 3 5 3 4 3 5 3 4 3 5 3 4 3 TREASURE HUNTS 12, 13 12 This is a rostral column in St Petersburg, Russia. -

The Complexity of Prime Number Tests

Die approbierte Originalversion dieser Diplom-/ Masterarbeit ist in der Hauptbibliothek der Tech- nischen Universität Wien aufgestellt und zugänglich. http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at The approved original version of this diploma or master thesis is available at the main library of the Vienna University of Technology. http://www.ub.tuwien.ac.at/eng The Complexity of Prime Number Tests Diplomarbeit Ausgeführt am Institut für Diskrete Mathematik und Geometrie der Technischen Universität Wien unter der Anleitung von Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Michael Drmota durch Theres Steiner, BSc Matrikelnummer: 01025110 Ort, Datum Unterschrift (Student) Unterschrift (Betreuer) The problem of distinguishing prime numbers from composite numbers and of re- solving the latter into their prime factors is known to be one of the most important and useful in arithmetic. Carl Friedrich Gauss, Disquisitiones Arithmeticae, 1801 Ron and Hermione have 2 children: Rose and Hugo. Vogon poetry is the 3rd worst in the universe. Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my parents, Rudolf and Doris Steiner, without them I would not be where I am now. I would also like to thank my professor Michael Drmota for supporting me and helping me with my thesis. Throughout the writing process he was always there for me and his input was always helpful. I would also like to thank my colleagues who made this stage of my life truly amazing. Also, a special thanks to the people that gave me valuable input on my thesis, mathematically or grammatically. 4 5 is the 5th digit in π. Abstract Prime numbers have been a signicant focus of mathematics throughout the years. -

Independence of the Miller-Rabin and Lucas Probable Prime Tests

Independence of the Miller-Rabin and Lucas Probable Prime Tests Alec Leng Mentor: David Corwin March 30, 2017 1 Abstract In the modern age, public-key cryptography has become a vital component for se- cure online communication. To implement these cryptosystems, rapid primality test- ing is necessary in order to generate keys. In particular, probabilistic tests are used for their speed, despite the potential for pseudoprimes. So, we examine the commonly used Miller-Rabin and Lucas tests, showing that numbers with many nonwitnesses are usually Carmichael or Lucas-Carmichael numbers in a specific form. We then use these categorizations, through a generalization of Korselt’s criterion, to prove that there are no numbers with many nonwitnesses for both tests, affirming the two tests’ relative independence. As Carmichael and Lucas-Carmichael numbers are in general more difficult for the two tests to deal with, we next search for numbers which are both Carmichael and Lucas-Carmichael numbers, experimentally finding none less than 1016. We thus conjecture that there are no such composites and, using multi- variate calculus with symmetric polynomials, begin developing techniques to prove this. 2 1 Introduction In the current information age, cryptographic systems to protect data have become a funda- mental necessity. With the quantity of data distributed over the internet, the importance of encryption for protecting individual privacy has greatly risen. Indeed, according to [EMC16], cryptography is allows for authentication and protection in online commerce, even when working with vital financial information (e.g. in online banking and shopping). Now that more and more transactions are done through the internet, rather than in person, the importance of secure encryption schemes is only growing.