Downloaded from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:41:12Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

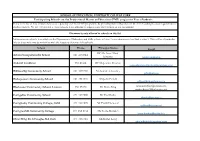

PME1 Schools List 2019-20

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK Participating Schools on the Professional Master of Education (PME) 2019/20 for Year 1 Students Below is the list of Post-Primary Schools co-operating on UCC's PME programme by providing School Placement in line with Teaching Council requirements for student teachers. We are very grateful to these schools for continuing to support such a key element of our programme Placement is only allowed in schools on this list. Information on schools is available on the Department of Education and Skills website at http://www.education.ie/en/find-a-school. This will be of particular help to those who may be unfamiliar with the locations of some of the schools. School Phone Principal Name Email DP Ms Anne Marie Ashton Comprehensive School 021 4966044 Hewison [email protected] Ardscoil na nDeise 058 41464 DP Ms Joanne Brosnan [email protected] Ballincollig Community School 021 4871740 Ms Kathleen Lowney [email protected] Bishopstown Community School 021 4544311 Mr John Farrell [email protected] Blackwater Community School, Lismore 058 53620 Mr Denis Ring [email protected]; [email protected] Carrigaline Community School 021 4372300 Mr Paul Burke [email protected] Carrignafoy Community College, Cobh 021 4811325 Mr Frank Donovan [email protected] Carrigtwohill Community College 021 485 3488 Ms Lorna Dundon [email protected] Christ King SS, S Douglas Rd, Cork 021 4961448 Ms Richel Long [email protected] Christian Brothers College, Cork 021 4501653 Mr. David -

Learning Neighbourhoods Pilot Programme

LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS PILOT PROGRAMME BALLYPHEHANE & KNOCKNAHEENY 2015–16 CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Background to Learning Neighbourhoods 4 2. Activities during the Pilot Year 9 2.1 UCC Learning Neighbourhood Lectures 10 2.2 Lifelong Learning Festival 12 2.2.1 ‘The Free University’ 12 2.2.2 Schools Visit to ‘The Free University’ 13 2.2.3 Ballyphehane Open Morning and UNESCO Visit 13 2.3 Faces of Learning Poster Campaign 14 2.4 Ballyphehane ‘How to Build a Learning Neighbourhood’ 16 2.5 Knocknaheeny and STEAM Education 17 2.6 Media and PR 18 2.7 National and International Collaborations, Presentations and Reports 20 3. Awards and Next Steps 24 This document was prepared by Dr Siobhán O'Sullivan and Lorna Kenny, SECTION 1 Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS STEERING GROUP Background to Learning Neighbourhoods has been supported during the pilot year by the Learning Neighbourhoods members of the Steering Group • Denis Barrett, Cork Education and Training Board • Lorna Kenny, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Willie McAuliffe, Learning Cities Chair • Clíodhna O’Callaghan, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Siobhán O’Dowd, Ballyphehane Togher Community Development Project • Dr Siobhán O’Sullivan, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Dr Séamus O’Tuama, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Nuala Stewart, City Northwest Quarter Regeneration, Cork City Council What is a Learning Neighbourhood? A Learning Neighbourhood is an area that has an ongoing commitment to learning, providing inclusive and diverse learning opportunities for whole communities through partnership and collaboration. 2 LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS SECTION 1 / BACKGROUND TO LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS In September 2015, the UNESCO Institute for 25) and also exhibits persistent socio-economic Residents of Lifelong Learning presented Cork with a Learning deprivation. -

UCC Access Programme External Evaluation

University College Cork Access Programme EXTERNAL EVALUATION University College Cork Access Programme EXTERNAL EVALUATION University College Cork Access Programme Evaluation report Cynthia Deane Options Consulting May 2003 Contents Executive summary 1. Introduction p09 1.1 Aims of evaluation p09 1.2 Evaluation methodology p11 2. Outline description of Access programme p13 2.1 Schools programme p14 2.2 Special admissions procedure p29 2.3 Post entry support time p34 2.4 Promotional literature and web site p43 2.5 Staff development p45 3. Feedback from programme participants p50 3.1 Focus group of current Access p50 Programme students 3.2 Questionnaire to current Access students p54 3.3 Interview with group of prospective Access p59 students attending Easter school 3.4 Focus group of principals and teachers p61 from programme linked schools 3.5 Interview with UCC Admissions Officer p68 4. Conclusions and recommendations p72 4.1 Main strengths of the UCC Access Programme p72 4.2 Recommendations for the future p77 Appendices Appendix 1 Schools involved with the Access programme, and the years in which they joined Appendix 2 Special admissions procedure Appendix 3 Questionnaire for students March 2003 Executive Summary This independent evaluation aimed to assess the effectiveness, impact, and sustainability of the UCC Access Programme, which has been in operation since 1996. The evaluation focused on the implementation of the project over a three- year period from 1999 to 2002. It is essentially qualitative in nature, including a description of programme activities and feedback from participants. The key outcomes of the Access Programme are described, and issues and options for the future are identified. -

Cork Learning Neighbourhoods Contents

CORK LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Background to Learning Neighbourhoods 4 2. Learning Neighbourhood Activities 2016: Ballyphehane and Knocknaheeny 9 (POSTER) How to build a Learning Neighbourhood? 20 3. Learning Neighbourhood Activities 2017: Mayfield & Togher 24 4. Media and PR, National & International Collaborations 32 5. Awards 38 This document was prepared by Dr Siobhán O'Sullivan and Lorna Kenny, Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS STEERING GROUP Learning Neighbourhoods has been supported by the members of the Steering Group: • Denis Barrett, Cork City Learning Coordinator, formerly Cork Education and Training Board SECTION 1 • Deirdre Creedon, CIT Access Service • Sarah Gallagher, Togher Youth Resilience Project • Lorna Kenny, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Willie McAuliffe, Learning Cities Chair • Clíodhna O’Callaghan, Adult Continuing Education, UCC Background to • Siobhán O’Dowd, Ballyphehane Togher Community Development Project • Liz O’Halloran, Mayfield Integrated Community Development Project/Mayfield Community Adult Learning Project C.A.L.P. Learning Neighbourhoods • Sandra O’Meara, Cork City Council RAPID • Sinéad O’Neill, Adult & Community Education Officer, UCC • Dr Siobhán O’Sullivan, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Dr Séamus O’Tuama, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Nuala Stewart, City Northwest Quarter Regeneration, Cork City Council A particular word of thanks to Sara Dalila Hočevar, who worked with Learning Neighbourhoods on an ERASMUS placement in 2017. What is a Learning Neighbourhood? Cork Learning City defines a Learning Neighbourhood as an area that has an ongoing commitment to learning, providing inclusive and diverse learning opportunities for whole communities through partnership and collaboration. 2 LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS SECTION 1 / BACKGROUND TO LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS In September 2015, the UNESCO Institute for Knocknaheeny in the north of the city. -

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK SPORTS STRATEGY 2019–2022 Vision the Globally Renowned Go-To University for Sport and Physical Activity in Ireland

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK SPORTS STRATEGY 2019–2022 Vision The globally renowned go-to university for sport and physical activity in Ireland Purpose Realise and unleash the potential of UCC sport and physical activity Mantra Pride on our chest. Belief in our heart. Sport in our bones. UCC SPORTS STRATEGY 2019 – 2022 CONTENTS Foreword 3 UCC Sports Strategy: Summary 4 Timeline 2019–2022 6 Introduction 8 UCC Sports Strategy Planning and Consultation Process 10 UCC Sports Strategy Context 11 Vision For Sport and Physical Activity in UCC 19 Strategic Priorities 21 2 PRIDE ON OUR CHEST. BELIEF IN OUR HEART. SPORT IN OUR BONES. UCC SPORTS STRATEGY 2019 – 2022 3 FOREWORD University College Cork has a deep and proud history of between our clubs and coaches; the Department of sporting achievement, and strong ambitions for the Sport and Physical Activity; Mardyke Arena, our sporting future. The importance of sport goes much further than facilities; and a range of academic disciplines and empowering people with health and wellbeing – sport research activities. The scholarship of sport, in the teaches life lessons of confidence, teamwork, respect, context of UCC’s tradition of research and teaching ambition, discipline, integrity and it provides a source of excellence, will sharpen our edge to push the boundaries great enjoyment. Through sport we learn that, no matter of sport through education, research and innovation. what the result, we must persevere and not give up. It gives me great pleasure to introduce this strategy for UCC is a connected university, and sport plays an sport, which sets out 27 specific actions to be important role in connecting student and alumni implemented across six priority areas over the short, communities, and engaging with the wider community. -

Designing and Implementing Neighborhoods of Learning in Cork’S Unesco Learning City Project

DESIGNING AND IMPLEMENTING NEIGHBORHOODS OF LEARNING IN CORK’S UNESCO LEARNING CITY PROJECT Séamus Ó Tuama, Ph.D.1 Siobhán O’Sullivan, Ph.D.2 ABSTRACT: Cork, the Republic of Ireland’s second most populous city, is one of 12 UNESCO Learning Cities globally. Becoming a learning city requires a sophisticated audit of education, learning and other socio-economic indicators. It also demands that cities become proactively engaged in delivering to the objectives set by the Beijing Declaration on Building Learning Cities which was adopted at the first UNESCO International Conference on Learning Cities in Beijing (2013) and the Mexico City Statement on Sustainable Learning Cities from the second conference in Mexico City (2015). The UNESCO learning city approach lays heavy emphasis on lifelong learning and social inclusion. In addressing these two concerns Cork city is piloting the development of two Learning Neighborhoods. The pilots are a collaboration between the City Council, University College Cork and Cork Education and Training Board who will work with the learning and education organizations and residents in each area to promote, acknowledge and show case active local lifelong learning. This paper looks at the context and design of these Learning Neighborhoods. Keywords: Learning City, Neighborhood Learning, UNESCO, Cork Cork: A UNESCO Learning City Cork City was granted the UNESCO Learning City Award at the second UNESCO International Conference on Learning Cities in Mexico City in September 2015. A total of twelve cities were granted the award viz. Melton (Australia), Sorocaba (Brazil), Beijing (China), Bahir Dar (Ethiopia), Espoo (Finland), Cork (Ireland), Amman (Jordan), Mexico City (Mexico), Ybycuí (Paraguay), Balanga (Philippines), Namyangju (Republic of Korea) and Swansea (United Kingdom). -

Cork City Attractions (Pdf)

12 Shandon Tower & Bells, 8 Crawford Art Gallery 9 Elizabeth Fort 10 The English Market 11 Nano Nagle Place St Anne’s Church 13 The Butter Museum 14 St Fin Barre’s Cathedral 15 St Peter’s Cork 16 Triskel Christchurch TOP ATTRACTIONS IN CORK C TY Crawford Art Gallery is a National Cultural Institution, housed in one of the most Cork City’s 17th century star-shaped fort, built in the aftermath of the Battle Trading as a market since 1788, it pre-dates most other markets of it’s kind. Nano Nagle Place is an historic oasis in the centre of bustling Cork city. The The red and white stone tower of St Anne’s Church Shandon, with its golden Located in the historic Shandon area, Cork’s unique museum explores the St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral is situated in the centre of Cork City. Designed by St Peter’s Cork situated in the heart of the Medieval town is the city’s oldest Explore and enjoy Cork’s Premier Arts and Culture Venue with its unique historic buildings in Cork City. Originally built in 1724, the building was transformed of Kinsale (1601) Elizabeth Fort served to reinforce English dominance and Indeed Barcelona’s famous Boqueria market did not start until 80 years after lovingly restored 18th century walled convent and contemplative gardens are salmon perched on top, is one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. One of the history and development of: William Burges and consecrated in 1870, the Cathedral lies on a site where church with parts of the building dating back to 12th century. -

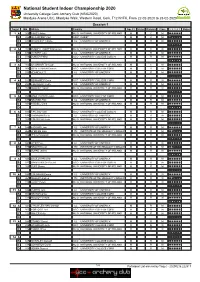

Integrated Result System

National Student Indoor Championship 2020 University College Cork Archery Club (NSIC2020) Mardyke Arena UCC, Mardyke Walk, Western Road, Cork, T12 N1FK, From 22-02-2020 to 23-02-2020 Session 1 Target Bib Athlete Country Age Cl. Subclass Division Class 1 2 3 4 5 Status 1 A 100 FAHEY Adam NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M C M B 032 MCCAFFREY Carl GUEST GUEST M G M C 035 MCGREEVY Charlie UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M D 2 A 101 RUSSELL-COWEN Shannon NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND W C W B 036 VICKERY Luke UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M C 016 DUNLEA Phillip UCD UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN M R M D 3 A 102 O'CONNOR Turlough NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M C M B 009 O'CALLAGHAN Cormac UCC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK M R M C 039 KENNEALY Tj UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M D 4 A 012 REINHARDT Carla UCC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK W R W B 033 COUGHLAN Keith UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M C 103 MOONEY Róisín NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND W R W D 5 A 003 O'SULLIVAN Brendan UCC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK M R M B 037 KEATING Finn UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M C 104 RIDDELL Chris NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M R M D 6 A 015 TAN Jing Yuan UCD UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN M R M B 038 CHAPMAN Sarah UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK W R W C 105 COUGHLAN Josh NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M R M D 7 A 040 HIGGINS Liam UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M B 069 O' BRIEN Liam ITC INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CARLOW M R M C 106 PFETZING Oisín NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M R M D 8 A 042 WEST Eva UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK W R W B 070 KEOGH Kieran ITC -

Thinking of Selling?

6,000 FREE THINKING OF SELLING? Also available at outlets in Mayfield, Upper Glanmire, Whites Cross, Watergrasshill, Glounthaune, Little Island, Carrigtwohill, Lisgoold, Carrignavar, Whitechurch & Knockraha. LOCAL COMPANY THE DIFFERENCE IS WE DELIVER Issue 3 - March 2015 GLOBAL AUDIENCE www.glanmireareacork.com e-mail- [email protected] M:086 8294713 SUPPORT US ON GAP OF DUNLOE WALK IN AID OF CANCER RESEARCH - SATURDAY MARCH 28th. Joe Organ Rena Guildea On Saturday March 28th, in the Joe Organ Auctioneers morning, at 8.30 on the dot, we will Mobile: 086 6013222 meet and leave from the library in Hazelwood by coach, to go to Killar- Phone: 021 2428620 ney and on to Kate Kearney’s. email [email protected] www.joeorganauctioneers.ie We will have time for a coffee/tea Office 2B Crestfield Centre, Glanmire. and a scone before walking the 11 km through the Gap of Dunloe; this takes between 2 and 2 and a half hours and leads us to Lord Brandon’s cottage. Time for something to eat, either bring your own or you can avail of what is available in the line of soup and sandwiches (and their delicious fruitcake). At 2 o’clock the boatmen will be ready to take us down the river and along the lake to Muckross House. The coach will be there to meet us and take us back to Hazelwood for about 6.30. The cost is a minimum of 40 euro, if you wish to give us more, it will be much appreciated of course! This will cover coach and boat, all food and drink you will have to pay for yourself separately. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Including children's voices in a multiple stakeholder study on a community-wide approach to improving quality in early years settings Author(s) Martin, Shirley; Buckley, Lynn Publication date 2018-10-29 Original citation Martin, S. and Buckley, L. (2018) 'Including children's voices in a multiple stakeholder study on a community-wide approach to improving quality in early years settings', Early Childhood Development and Care. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2018.1538135 Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1538135 version http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1538135 Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2018, Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an original manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Early Child Development and Care on 29 October 2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/03004430.2018.1538135 Embargo information Access to this article is restricted until 18 months after publication by request of the publisher. Embargo lift date 2020-04-29 Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/7917 from Downloaded on 2021-09-28T13:39:19Z 1. Title Including children’s voices in a multiple stakeholder study on a community wide approach to improving quality in early years setting 2. Author details. Corresponding author:: Dr Shirley Martin, School of Applied Social Studies, University College Cork, Ireland, [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7784-5907 Lynn Buckley, Research Assistant and Information Officer with the Young Knocknaheeny Area based Childcare Programme. -

Grid Export Data

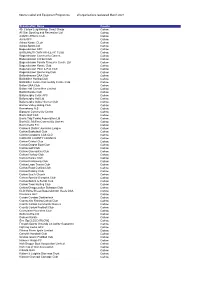

Sports Capital and Equipment Programme all organisations registered March 2021 Organisation Name County 4th Carlow Leighlinbrige Scout Group Carlow All Star Sporting and Recreation Ltd Carlow Ardattin Athletic Club Carlow Asca GFC Carlow Askea Karate CLub Carlow Askea Sports Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown AFC Carlow BAGENALSTOWN ATHLETIC CLUB Carlow Bagenalstown Community Games Carlow Bagenalstown Cricket Club Carlow Bagenalstown Family Resource Centre Ltd Carlow Bagenalstown Karate Club Carlow Bagenalstown Pitch & Putt Club Carlow Bagenalstown Swimming Club Carlow Ballinabranna GAA Club Carlow Ballinkillen Hurling Club Carlow Ballinkillen Lorum Community Centre Club Carlow Ballon GAA Club Carlow Ballon Hall Committee Limited Carlow Ballon Karate Club Carlow Ballymurphy Celtic AFC Carlow Ballymurphy Hall Ltd Carlow Ballymurphy Indoor Soccer Club Carlow Barrow Valley Riding Club Carlow Bennekerry N.S Carlow Bigstone Community Centre Carlow Borris Golf Club Carlow Borris Tidy Towns Association Ltd Carlow Borris/St. Mullins Community Games Carlow Burrin Celtic F.C. Carlow Carlow & District Juveniles League Carlow Carlow Basketball Club Carlow Carlow Carsports Club CLG Carlow CARLOW COUNTY COUNCIL Carlow Carlow Cricket Club Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club Carlow Carlow Golf Club Carlow Carlow Gymnastics Club Carlow Carlow Hockey Club Carlow Carlow Karate Club Carlow Carlow Kickboxing Club Carlow Carlow Lawn Tennis Club Carlow Carlow Road Cycling Club Carlow Carlow Rowing Club Carlow Carlow Scot's Church Carlow Carlow Special Olympics Club Carlow Carlow -

Martin Finnin Was Born in 1968. He Lives and Works in Cork, Ireland

Martin Finnin was born in 1968. He lives and works in Cork, Ireland. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 The Wolf of Eyelash Mountain, John Martin Gallery, London 2013 Renegade Amongst the Dusty Nouns, John Martin Gallery, London 2012 Dust, Dots and a Day in the Maze, John Martin Gallery, London 2011 The Forgotten Art of Floating, Cornexchange Gallery, Edinburgh 2010 49 Oxhides and a Lump of Faith, John Martin Gallery, London 2009 The Moon and the Modern World, Origin Gallery, Dublin 2009 Old Rain, New Eyes, Vangard Gallery, Cork 2008 Turn the Lemon Page, Cill Rialaig Art Centre, Ballinskelligs, Kerry 2007 John Martin Gallery, ART LONDON, Chelsea, London 2007 A Snippet from the Seventh Soup, Vangard Gallery, Cork 2006 The World is Blue like an Orange, Urban Retreat Gallery, Dublin 2006 Stepping out of the Stream of Time, Printmakers Gallery, Limerick 2006 Life Beyond the Hedge, Cill Rialaig Art Centre, Ballinskelligs, Co Kerry 2005 The Miracle Outside the Window, Form Gallery, London 2005 The Marching Hugs, Origin Gallery, Dublin 2005 Meanwhile.. in a Foreign Land, Vangard Gallery, Cork 2003 The Origins of Optimism, Printmakers Gallery, Limerick 2003 Songs of Recluse, Vangard Gallery, Cork 2003 In Fall, Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin 2002 Vermont Studio Gallery, Vermont 2001 A Subtle Consolation of Existence, Vangard Gallery, Cork 2001 The Big Picture, Printmakers Gallery, Limerick 1997 Forest of Banquets, Tig Filí Gallery, Cork 1996 Spionza, Blackcombe Gallery, Cork 1996 Gaia, Triskel Art Centre, Cork 1995 Ivory Tower, Cork 1995 Jo Rain Gallery, Dublin