Designing and Implementing Neighborhoods of Learning in Cork’S Unesco Learning City Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

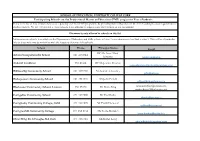

PME1 Schools List 2019-20

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK Participating Schools on the Professional Master of Education (PME) 2019/20 for Year 1 Students Below is the list of Post-Primary Schools co-operating on UCC's PME programme by providing School Placement in line with Teaching Council requirements for student teachers. We are very grateful to these schools for continuing to support such a key element of our programme Placement is only allowed in schools on this list. Information on schools is available on the Department of Education and Skills website at http://www.education.ie/en/find-a-school. This will be of particular help to those who may be unfamiliar with the locations of some of the schools. School Phone Principal Name Email DP Ms Anne Marie Ashton Comprehensive School 021 4966044 Hewison [email protected] Ardscoil na nDeise 058 41464 DP Ms Joanne Brosnan [email protected] Ballincollig Community School 021 4871740 Ms Kathleen Lowney [email protected] Bishopstown Community School 021 4544311 Mr John Farrell [email protected] Blackwater Community School, Lismore 058 53620 Mr Denis Ring [email protected]; [email protected] Carrigaline Community School 021 4372300 Mr Paul Burke [email protected] Carrignafoy Community College, Cobh 021 4811325 Mr Frank Donovan [email protected] Carrigtwohill Community College 021 485 3488 Ms Lorna Dundon [email protected] Christ King SS, S Douglas Rd, Cork 021 4961448 Ms Richel Long [email protected] Christian Brothers College, Cork 021 4501653 Mr. David -

Learning Neighbourhoods Pilot Programme

LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS PILOT PROGRAMME BALLYPHEHANE & KNOCKNAHEENY 2015–16 CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Background to Learning Neighbourhoods 4 2. Activities during the Pilot Year 9 2.1 UCC Learning Neighbourhood Lectures 10 2.2 Lifelong Learning Festival 12 2.2.1 ‘The Free University’ 12 2.2.2 Schools Visit to ‘The Free University’ 13 2.2.3 Ballyphehane Open Morning and UNESCO Visit 13 2.3 Faces of Learning Poster Campaign 14 2.4 Ballyphehane ‘How to Build a Learning Neighbourhood’ 16 2.5 Knocknaheeny and STEAM Education 17 2.6 Media and PR 18 2.7 National and International Collaborations, Presentations and Reports 20 3. Awards and Next Steps 24 This document was prepared by Dr Siobhán O'Sullivan and Lorna Kenny, SECTION 1 Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS STEERING GROUP Background to Learning Neighbourhoods has been supported during the pilot year by the Learning Neighbourhoods members of the Steering Group • Denis Barrett, Cork Education and Training Board • Lorna Kenny, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Willie McAuliffe, Learning Cities Chair • Clíodhna O’Callaghan, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Siobhán O’Dowd, Ballyphehane Togher Community Development Project • Dr Siobhán O’Sullivan, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Dr Séamus O’Tuama, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Nuala Stewart, City Northwest Quarter Regeneration, Cork City Council What is a Learning Neighbourhood? A Learning Neighbourhood is an area that has an ongoing commitment to learning, providing inclusive and diverse learning opportunities for whole communities through partnership and collaboration. 2 LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS SECTION 1 / BACKGROUND TO LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS In September 2015, the UNESCO Institute for 25) and also exhibits persistent socio-economic Residents of Lifelong Learning presented Cork with a Learning deprivation. -

UCC Access Programme External Evaluation

University College Cork Access Programme EXTERNAL EVALUATION University College Cork Access Programme EXTERNAL EVALUATION University College Cork Access Programme Evaluation report Cynthia Deane Options Consulting May 2003 Contents Executive summary 1. Introduction p09 1.1 Aims of evaluation p09 1.2 Evaluation methodology p11 2. Outline description of Access programme p13 2.1 Schools programme p14 2.2 Special admissions procedure p29 2.3 Post entry support time p34 2.4 Promotional literature and web site p43 2.5 Staff development p45 3. Feedback from programme participants p50 3.1 Focus group of current Access p50 Programme students 3.2 Questionnaire to current Access students p54 3.3 Interview with group of prospective Access p59 students attending Easter school 3.4 Focus group of principals and teachers p61 from programme linked schools 3.5 Interview with UCC Admissions Officer p68 4. Conclusions and recommendations p72 4.1 Main strengths of the UCC Access Programme p72 4.2 Recommendations for the future p77 Appendices Appendix 1 Schools involved with the Access programme, and the years in which they joined Appendix 2 Special admissions procedure Appendix 3 Questionnaire for students March 2003 Executive Summary This independent evaluation aimed to assess the effectiveness, impact, and sustainability of the UCC Access Programme, which has been in operation since 1996. The evaluation focused on the implementation of the project over a three- year period from 1999 to 2002. It is essentially qualitative in nature, including a description of programme activities and feedback from participants. The key outcomes of the Access Programme are described, and issues and options for the future are identified. -

Autumn 2011 [email protected] Follow Us on Twitter: @Kinsalenews

Pic John Allen DRAGON GOLD CUP FOR KINSALE IN 2012... SÁILE FAMILY FUN DAY... 1st DAY AT SCHOOL ... DEBS PHOTOS... Vol. 34 No. 4 Est December 1976 by Frank Hurley Autumn 2011 www.kinsalenews.com [email protected] follow us on twitter: @kinsalenews Pic John Allen Footprints 20/21 Main Street, Kinsale Footprints 64A Main Street, Kinsale T/F: (021) 477 7898 T/F (021) 477 7032 Ladies & Gents Footwear Ladies & Childrens Footwear End of Season Clearance Sale Now On!!! The Blue Haven Collection Kinsale Christmas Party Packages To Suit Every Budget Tel: 021-4772209 Email: [email protected] The Collection Package • Accommodation @ The Blue Haven Hotel or The Old Bank Town House • Dinner @ the award winning Restaurant or Bistro at The Blue Haven Hotel or Seafood @ Aperitif Wine and Seafood Bar. www.bluehavencollection.com • Live Music in The Blue Haven / Seanachai Bar / DJ @ Hamlets Café Bar • Reserved area in Hamlets such as the VIP room. (Subject to availabilty) www.hamletsofkinsale.com • Passes to Studio Blue Night Club. We can reserve the exclusive Bollinger Lounge for you with its own private bar, hostess & smoking area • Party Nights €65 per person sharing The Blue Haven Package • Dinner @ the award winning Blue Haven Restaurant or Bistro at The Blue Haven Hotel www.bluehavenkinsale.com • Live Music in The Blue Haven / Seanachai Bar / DJ @ Hamlets Café Bar • Reserved area in Hamlets such as the VIP room. (Subject to availabilty). www.hamletsofkinsale.com • Passes to Studio Blue Night Club. We can reserve the exclusive Bollinger Lounge for you with its own private bar, hostess & smoking area • This package is €30 per person The Hamlets Package • Finger Food @ Hamlets Café Bar www.hamletsofkinsale.com • Live Music in The Blue Haven / Seanachai Bar / DJ @ Hamlets Café Bar • Reserved area in Hamlets such as the VIP room. -

Cork Learning Neighbourhoods Contents

CORK LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Background to Learning Neighbourhoods 4 2. Learning Neighbourhood Activities 2016: Ballyphehane and Knocknaheeny 9 (POSTER) How to build a Learning Neighbourhood? 20 3. Learning Neighbourhood Activities 2017: Mayfield & Togher 24 4. Media and PR, National & International Collaborations 32 5. Awards 38 This document was prepared by Dr Siobhán O'Sullivan and Lorna Kenny, Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS STEERING GROUP Learning Neighbourhoods has been supported by the members of the Steering Group: • Denis Barrett, Cork City Learning Coordinator, formerly Cork Education and Training Board SECTION 1 • Deirdre Creedon, CIT Access Service • Sarah Gallagher, Togher Youth Resilience Project • Lorna Kenny, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Willie McAuliffe, Learning Cities Chair • Clíodhna O’Callaghan, Adult Continuing Education, UCC Background to • Siobhán O’Dowd, Ballyphehane Togher Community Development Project • Liz O’Halloran, Mayfield Integrated Community Development Project/Mayfield Community Adult Learning Project C.A.L.P. Learning Neighbourhoods • Sandra O’Meara, Cork City Council RAPID • Sinéad O’Neill, Adult & Community Education Officer, UCC • Dr Siobhán O’Sullivan, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Dr Séamus O’Tuama, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Nuala Stewart, City Northwest Quarter Regeneration, Cork City Council A particular word of thanks to Sara Dalila Hočevar, who worked with Learning Neighbourhoods on an ERASMUS placement in 2017. What is a Learning Neighbourhood? Cork Learning City defines a Learning Neighbourhood as an area that has an ongoing commitment to learning, providing inclusive and diverse learning opportunities for whole communities through partnership and collaboration. 2 LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS SECTION 1 / BACKGROUND TO LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS In September 2015, the UNESCO Institute for Knocknaheeny in the north of the city. -

Week Ending 23-08-2019

CORK CITY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 19/08/2019 TO 23/08/2019 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: Cork City FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE RECEIVED DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS RECD. PROT STRU IPC LIC. WASTE LIC. 19/38630 O Cualann Cohousing Alliance CLG Permission 19/08/2019 Permission for Construction of 17 no. Affordable Residential Units No No No No comprising : 1 two bed 2 story house, 9 three bed 2 story houses and 1 four bed 3 story arranged in a terrace, and to the East, 6 two bed apartments in a three storey block including balconies at first floor and second floor level facing West. The proposal includes 19no car parking spaces (8no on-street and 11no off-street) 6no cycling bars, ancillary site works 9including individual refuse storage areas) and landscaping, all on lands totalling 0.2219Ha forming part of the Cork City North West Quarter Regeneration. At: The site is bounded by Dunmore Gardens to the North, Kilmore Road Lower to the South, (all part of the Cork City North West Quarter Regeneration Area) and Existing Houses to the West. -

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL 15Th March

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL 15th March 2018 Árd Mheara agus Comhairleoirí REPORT ON WARD FUNDS PAID IN 2017 The following is a list of payees who received Ward Funds from Members in 2017: Payee Amount € 17/51ST SCOUTS BLACKROCK 150 37TH CORK SCOUT GROUP 100 38TH/40TH BALLINLOUGH SCOUT GR 600 43RD/70TH CORK BISHOPSTOWN SCO 650 53RD CORK SCOUT TROOP 1400 5TH CORK LOUGH SCOUTS 150 AGE ACTION IRELAND 475 AGE LINK MAHON CDP 200 ALZHEIMER SOCIETY OF IRELAND 100 ARD NA LAOI RESIDENTS ASSOC 650 ART LIFE CULTURE LTD 350 ASCENSION BATON TWIRLERS 1000 ASHDENE RES ASSOC 650 ASHGROVE PARK RESIDENTS ASSOCI 250 ASHMOUNT RESIDENTS ASSOCIATION 200 AVONDALE UTD F.C. 450 AVONMORE PARK RESIDENTS ASSOCI 600 BAILE BEAG CHILDCARE LTD 700 BALLINLOUGH COMMUNITY ASSOCIAT 1150 BALLINLOUGH MEALS ON WHEELS 250 BALLINLOUGH PITCH AND PUTT CLU 250 BALLINLOUGH RETIREMENT CLUB 200 BALLINLOUGH SCOUT GROUP 650 BALLINLOUGH SUMMER SCHEME 850 BALLINLOUGH YOUTH CLUB 500 BALLINLOUGH YOUTH SUMMER FESTI 200 BALLINURE GAA CLUB 450 BALLYPHEHANE COMMUNITY CENTRE 500 BALLYPHEHANE DISTRICT PIPE BAN 650 BALLYPHEHANE GAA CLUB 1120 BALLYPHEHANE GAA CLUB JUNIOR S 200 BALLYPHEHANE LADIES CLUB 120 BALLYPHEHANE LADIES FOOTBALL C 1200 BALLYPHEHANE MEALS ON WHEELS 250 BALLYPHEHANE MENS SHED 1000 BALLYPHEHANE PIPE BAND 450 BALLYPHEHANE TOGHER CDP LTD PP 300 BALLYPHEHANE YOUTH CAFE 100 BALLYPHEHANE/TOGHER ARTS INITI 350 BALLYPHEHANE/TOGHER CDP 200 BALLYPHEHANE/TOGHER COMMUNITY 450 BALLYVOLANE COMMUNITY ASSOCIAT 200 BALTIMORE LAWN RESIDENTS ASSOC 150 BARRS CAMOGIE STREET LEAGUE -

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK SPORTS STRATEGY 2019–2022 Vision the Globally Renowned Go-To University for Sport and Physical Activity in Ireland

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK SPORTS STRATEGY 2019–2022 Vision The globally renowned go-to university for sport and physical activity in Ireland Purpose Realise and unleash the potential of UCC sport and physical activity Mantra Pride on our chest. Belief in our heart. Sport in our bones. UCC SPORTS STRATEGY 2019 – 2022 CONTENTS Foreword 3 UCC Sports Strategy: Summary 4 Timeline 2019–2022 6 Introduction 8 UCC Sports Strategy Planning and Consultation Process 10 UCC Sports Strategy Context 11 Vision For Sport and Physical Activity in UCC 19 Strategic Priorities 21 2 PRIDE ON OUR CHEST. BELIEF IN OUR HEART. SPORT IN OUR BONES. UCC SPORTS STRATEGY 2019 – 2022 3 FOREWORD University College Cork has a deep and proud history of between our clubs and coaches; the Department of sporting achievement, and strong ambitions for the Sport and Physical Activity; Mardyke Arena, our sporting future. The importance of sport goes much further than facilities; and a range of academic disciplines and empowering people with health and wellbeing – sport research activities. The scholarship of sport, in the teaches life lessons of confidence, teamwork, respect, context of UCC’s tradition of research and teaching ambition, discipline, integrity and it provides a source of excellence, will sharpen our edge to push the boundaries great enjoyment. Through sport we learn that, no matter of sport through education, research and innovation. what the result, we must persevere and not give up. It gives me great pleasure to introduce this strategy for UCC is a connected university, and sport plays an sport, which sets out 27 specific actions to be important role in connecting student and alumni implemented across six priority areas over the short, communities, and engaging with the wider community. -

Cork City August 2019

CORK CITY AUGUST 2019 MOTHER JONES FLEA FEM – ALE CELEBRATING THE LEE SESSIONS BAM CORK CITY SPORTS MARKET WOMEN IN BREWING TRADITIONAL MUSIC 14 AUGUST YORK HILL OFF AUGUST 9 TO 10 WWW.THELEESESSIONS.IE CIT STADIUM MACCURTAIN ST FRANCISCAN WELL NORTH BISHOPSTOWN FRIDAY TO SUNDAY MALL WWW.CORKSPORTSDAY. 10AM TO 6PM WWW.FRANCISCANWELLBR IE FB/MOTHERJONESFLEAM EWERY.COM ARKET DATE TIME CATEGORY EVENT VENUE & CONTACT PRICE Monday 7.30pm Dancing Learn Irish Dancing Crane Lane Theatre Phoenix St €5 www.cranelanetheatre.ie Monday 9pm Blues One Horse Pony Franciscan Well North Mall Free 0214393434 Monday 6.30pm Trad Music Traditional Music Sin é Coburg St Free 0214502266 Monday 9.30pm Poetry O’Bheal Poetry Night The Hayloft @ The Long Valley Free Winthrop St www.obheal.ie Monday 9pm Music Rebel Red Sessions- Costigan’s Pub Washington St Free Roy Buckley 0214273340 Monday 9pm Band The Americhanics Coughlan’s Douglas St Free www.coughlans.ie Tuesday 8.30pm Trad Session Traditional Music Session The Franciscan Well North Mall Free 0214393434 Tuesday 8.30pm Comedy Comedy Cavern Coughlan’s Douglas St Free www.coughlans.ie Tuesday 7pm Comedy History Hysterical Histories – A An Spailpín Fánach South Main €28/€25/€2 Unique Dinner Theatre St 0876419355 0 Experience Tuesday 12noon Butter Butter Making Cork Butter Museum O’Connell €4/€3 Demonstration Sq. Shandon www.corkbutter.museum Tuesday 9.30pm Music Rebel Red Sessions - Costigan’s Pub Washington St Free Lee O’Donovan 0214273350 Disclaimer: The events listed are subject to change please contact the -

The Archive JOURNAL of the CORK FOLKLORE PROJECT IRIS BHÉALOIDEAS CHORCAÍ ISSN 1649 2943 21 UIMHIR FICHE a HAON

The Archive JOURNAL OF THE CORK FOLKLORE PROJECT IRIS BHÉALOIDEAS CHORCAÍ ISSN 1649 2943 21 UIMHIR FICHE A HAON FREE COPY The Archive 21 | 2017 Contents PROJECT MANAGER 3 Introduction Dr Tomás Mac Conmara No crew cuts or new-fangled styles RESEARCH DIRECTOR 4 Mr. Lucas - The Barber. By Billy McCarthy Dr Clíona O’Carroll A reflection on the Irish language in the Cork Folklore 5 EDITORIAL ADVISOR Project Collection by Dr. Tomás Mac Conmara Dr Ciarán Ó Gealbháin The Loft - Cork Shakespearean Company 6 By David McCarthy EDITORIAL TEAM Dr Tomás Mac Conmara, Dr Ciarán Ó The Cork Folklore Masonry Project 10 By Michael Moore Gealbháin, Louise Madden-O’Shea The Early Days of Irish Television PROJECT RESEARCHERS 14 By Geraldine Healy Kieran Murphy, Jamie Furey, James Joy, Louise Madden O’Shea, David McCarthy, Tomás Mac Curtain in Memory by Dr. Tomás Mac 16 Conmara Mark Foody, Janek Flakus Fergus O’Farrell: A personal reflection GRAPHIC DESIGN & LAYOUT 20 of a Cork music pioneer by Mark Wilkins Dermot Casey 23 Book Reviews PRINTERS City Print Ltd, Cork Boxcars, broken glass and backers: Ballyphehane Oral www.cityprint.ie 24 History Project by Jamie Furey 26 A Taste of Tripe by Kieran Murphy The Cork Folklore Project Northside Community Enterprises Ltd facebook.com/corkfolklore @corkfolklore St Finbarr’s College, Farranferris, Redemption Road, Cork, T23YW62 Ireland phone +353 (021) 422 8100 email [email protected] web www.ucc.ie/cfp Acknowledgements Disclaimer The Cork Folklore Project would like to thank : Dept of Social Protection, The Cork Folklore Project is a Dept of Social Protection funded joint Susan Kirby; Management and staff of Northside Community Enterprises; Fr initiative of Northside Community Enterprises Ltd & Dept of Folklore and John O Donovan, Noreen Hegarty; Roinn an Bhéaloideas / Dept of Folklore Ethnology, University College Cork. -

Turn the Spotlight on Your Fitness Career

The Glanmire Chamber of Commerce main aim in the Glanmire area for Christmas shopping is to ‘Keep Business in Glanmire’. Over the next and create a Christmas atmosphere through few months and years the Chamber hopes to festive lighting. This lighting project will give increase business in the Glanmire Area by sup- the Glanmire economy a boost. porting and networking businesses together. Glanmire Chamber of Commerce caters for all The Glanmire Chamber is a newly setup organ- businesses, be they start-ups, small family run isation by business men and women in Glan- or well-established businesses. It is our objec- mire wanting to keep the business in Glanmire. tive to represent your business and provide the The Chamber was enacted to help create local necessary support, network and resources to knowledge of the different businesses located grow. in Glanmire and to create business networking. For further information on the Chamber and The Chamber will be led by the officers (in the to join, the cost of membership for 12 months picture below) who have a wide range of busi- is €125. Membership forms are available from ness expertise and experience. any of the officers listed above or email glan- Future Projects in the [email protected]. Keep an eye on the Glanmire Area include: September issue of the Glanmire Area News Officers of The Glanmire Chamber of Operation Christmas Lighting: for full details of our networking events. The Commerce, Left to Right: John McCarthy This Christmas the Chamber would like to launch and information night of the Chamber (PRO), Michael O’Dowd (Vice President), Kathleen Worth (Treasurer), Joe Organ show that Christmas has arrived in Glanmire by will be held in Cafe Beva on the 15th Sep- (President), Jon Moran (Secretary) funding a Christmas lighting project in Glan- tember 2016. -

Cork City Attractions (Pdf)

12 Shandon Tower & Bells, 8 Crawford Art Gallery 9 Elizabeth Fort 10 The English Market 11 Nano Nagle Place St Anne’s Church 13 The Butter Museum 14 St Fin Barre’s Cathedral 15 St Peter’s Cork 16 Triskel Christchurch TOP ATTRACTIONS IN CORK C TY Crawford Art Gallery is a National Cultural Institution, housed in one of the most Cork City’s 17th century star-shaped fort, built in the aftermath of the Battle Trading as a market since 1788, it pre-dates most other markets of it’s kind. Nano Nagle Place is an historic oasis in the centre of bustling Cork city. The The red and white stone tower of St Anne’s Church Shandon, with its golden Located in the historic Shandon area, Cork’s unique museum explores the St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral is situated in the centre of Cork City. Designed by St Peter’s Cork situated in the heart of the Medieval town is the city’s oldest Explore and enjoy Cork’s Premier Arts and Culture Venue with its unique historic buildings in Cork City. Originally built in 1724, the building was transformed of Kinsale (1601) Elizabeth Fort served to reinforce English dominance and Indeed Barcelona’s famous Boqueria market did not start until 80 years after lovingly restored 18th century walled convent and contemplative gardens are salmon perched on top, is one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. One of the history and development of: William Burges and consecrated in 1870, the Cathedral lies on a site where church with parts of the building dating back to 12th century.