Complete Thesis.Mellel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 2021 at 10:00 AM

www.reddingauction.com 1085 Table Rock Road, Gettysburg, PA PH: 717-334-6941 Pennsylvania's Largest No Buyers Premium Gun Auction Service Your Professional FireArms Specialists With 127+ Combined Years of Experience Striving to Put Our Clients First & Achieving Highest Prices Realized as Possible! NO RESERVE – NO BUYERS PREMIUM If You Are Interested in Selling Your Items in an Upcoming Auction, Email [email protected] or Call 717- 334-6941 to Speak to Someone Personally. We Are Consistently Bringing Higher Prices Realized Than Other Local Auction Services Due to Not Employing a Buyer’s Premium (Buyer’s Penalty). Also, We Consistently Market Our Sales Nationally with Actual Content For Longer Periods of Time Than Other Auction Services. SATURDAY, AUGUST 28, 2021 at 10:00 AM PLEASE NOTE: -- THIS IS YOUR ITEMIZED LISTING FOR THIS PARTICULAR AUCTION PLEASE BRING IT WITH YOU WHEN ATTENDING Abbreviation Key for Ammo Lots: NIB – New in Box WTOC – Wrapped at Time of Cataloging (RAS Did Not Unwrap the Lots With This Designation in Order to Verify the Correctness & Round Count. We depend on our consignor’s honesty and integrity when describing sealed boxes. RAS Will Offer No Warranties or No Guarantees Regarding Count or the Contents Inside of These Boxes) Any firearms with a “R” after the lot number means it is a registrable firearm. Any firearms without the “R” is an antique & Mfg. Pre-1898 meaning No registration is required. Lot #: 1. Winchester – No. W-600 Caged Copper Room Heater w/Cord – 12½” Wide 16” High w/Gray Base (Excellent Label) 2. Winchester-Western – “Sporting Arms & Ammunition” 16” Hexagon Shaped Wall Clock – Mfg. -

Victory Hall WR IFT Feb 28 14

8'-11" 4 1/2" AREA 1 DEMOLITION 1. REMOVE EXISTING TOILET PARTITIONS, 3'-6" 5'-5" 3'-0" 3'-0" 3'-0" 3'-0" PLUMBING FIXTURES AND VANITY. EXHAUST FAN 2. REMOVE PORTION OF EXISTING WALL TO SUIT PROVIDE FRAMED 2'-0" NEW DOOR LOCATION. WT2 NEW 2x4 WALL BULKHEAD & EXHAUST 3. REMOVE EXISTING FLOOR TILES THROUGH EXTERIOR 4. REMOVE EXISTING BASE BOARD TRIM WALL TYP EF-1 EF-2 AREA 2 DEMOLITION AREA 1 1 1. REMOVE EXISTING TOILET PARTITIONS, 2'-0" BULKHEAD FOR E2 3 202 PLUMBING FIXTURES AND VANITY. EXHAUST FAN 3'-1" 2. REMOVE PORTION OF EXISTING WALL TO SUIT DUCT TO EXTERIOR NEW DOOR LOCATION. WALL SEE TYPICAL 3. REMOVE EXISTING FLOOR TILES E1 1 WT1 DETAIL 1 4. REMOVE EXISTING BASE BOARD TRIM 6'-4" E1 3 3 3 3 2 2 2'-8" E2 202 5'-6" 2 6 AREA 2 6 2'-7" 1 101 NEW 2'-10"x6'-8" DOOR 1 AREA 3 NEW 2x4 INFILL 4 102 WALL EF-2 INFILL STUD WALL 5 TO SUIT NEW DOOR LOCATION 7 NEW 2'-10"x6'-8" DOOR AREA 3 DEMOLITION 1. REMOVE PORTION OF EXISTING WALL TO SUIT NEW DOOR LOCATION. 6 PLAN 3/8"=1'-0" 3 DEMOLITION 3 E1 203 2 NOTE: E2 GENERAL NOTES CURRENT DESIGN & SPECIFICATIONS 1 1 SHOW MANUAL FLUSH TOILETS WITH 1.0 GENERAL 103 TANKS. CONTRACTOR TO PROVIDE OWNER WITH AN ADDITIONAL "ADD PRICE" 1. THE FOLLOWING NOTES ARE INTENDED TO SUMMARIZE THE 10. INSTALL NEW DOORS AS PER LAYOUT PLAN GENERAL INTENT OF THE OF THE WORK AND MUST NOT BE 11. -

Isaiah Davenport House Volunteer Newsletter January 2012 912/236-8097 Become a Facebook Fan at “Davenport House Museum”

Isaiah Davenport House Volunteer Newsletter January 2012 www.davenporthousemuseum.org 912/236-8097 Become a Facebook fan at “Davenport House Museum” The WEATHER – For the last four or DAVENPORT HOUSE CALENDAR Though the museum does not five weeks we have experienced the JANUARY 2012 need a lot of volunteers for this, if genial temperature of spring. Such has Sunday, January 1 – Museum you are able to volunteer time be- been the mildness of the season that Closed for New Year’s Day tween 9 a.m. and noon on Monday, sweet roses, jessamines and woodbines Tuesday, January 10 at 10:30 January 16, Tuesday, January 17 have put forth in the gardens of our city. a.m. – DHC planning for and Wednesday, January 18, let Yesterday at 12 o’clock, the Thermome- Preservation Fest Jamie know. tre stood at 72 degrees; by 9 o’clock last 12 noon – Davenport House Raleigh Marcell will coordi- night it was down to 58, and this morn- Committee nated cleaning for the week. ing at 12, it ranged at 47 degrees, mak- Thursday, January 12 at 2 p.m. – ing a difference of 25 degrees in 24 HSF/DH Preservation Fest COLLECTIONS: hours. The wind W. N. W. and blowing meeting On Friday, January 20 at 1:30 p.m. heavy. Saturday, January 14 at 1 p.m. – the Davenport House Committee’s Savannah Republican, January 19, 1824 2012 Oyster Roast Collections Committee will meet to Monday, January 16 through review the results of the cleaning, The Ladies. The longer a woman Friday, January 20 – DH An- assess the condition of the exhib- remains single, the more apprehensive nual Cleaning (museum closed) ited collections items and set goals she will be of entering into a state of Tuesday, January 17 at 6:30 p.m. -

08 04 2015 (Pdf)

8-4-15 Sect. 1.qxp:Layout 1 7/30/15 1:20 PM Page 1 Jackson County holds first fair on new grounds By Donna Sullivan, Editor clover is still prominent. A project that has been “The jury is still out on nine years in the making whether we are going to re- came to fruition as the Jack- paint it,” Nelson shared. Old son County Fair was held in panels have been repurposed its brand new facility south to make signs while gates of Holton this year. Wholly from the old hog barns have owned by the fair board, the been painted green and used purchase of the 50 acres the in landscaping. fairgrounds inhabits was Looking ahead, the board made possible in part by the has left options open for sale of the real estate that adding more buildings in the was previously home to the A 30,000-square-foot building now houses all the livestock pens as well as the show arena for the Jackson Coun- future, but is more focused Jackson County Fair. ty Fair. Photos by Donna Sullivan on being good stewards of Fundraisers too numerous to what they already have. “We mention, as well as the gen- want to be able to keep the erosity of many donors, al- doors open on what we have lowed the board to build two before we do anything dif- new buildings – one that was ferent,” Allen pointed out. finished a couple of years “The main thing we’ve ago and now contains the in- had a challenge with is that door project exhibits – and we as the board want to op- the other a 30,000- square- erate within our means,” foot building that houses all Nelson agreed. -

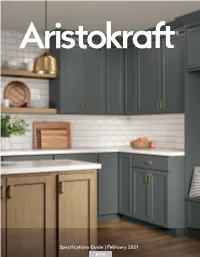

Spec Guide (PDF, 10.5

Specifications Guide | February 2021 ARISTOKRAFT WORKING HARD, CHECKING BOXES THAT ARE IMPORTANT TO YOU! Lead Times: Fast and Consistent Products: You’ll LOVE What You See Customer Service: Best in Class NOW Relevant doors in fashionable finishes Material selections your customers are asking for Storage and organization solutions for clutter control NEW Complementary doors, geared to meet any budget Trending colors for PureStyle and Paint Neutrality in stain color, creating a backdrop for living Fewer finish/door exclusions add ease in the design and sale of every project ARISTOKRAFT. WE’RE MORE THAN YOU’D EXPECT. Dayton Paint Greyhound , Trenton Birch Quill TRENTON DOOR STYLE Spec Book Page 18 A partial overlay sibling to the well-recieved Dayton door, Trenton is ready to deliver when price point is key. Good looks and timeless appeal make Trenton an asset to any design. Trenton • 2-7/32” stiles and rails, mortise and tenon construction • Birch – all stains and glaze • Paint- all colors • Slab Drawer Front • Partial Overlay • Flat Veneer Center Panel Glyn Birch Quill GLYN DOOR STYLE Spec Book Page 15 Building on the popularity of Sinclair, with a firm desire for a raised panel complement; the partial overlay styling of Glyn adds versatility to any aesthetic. Glyn • 2” stiles and rails mortise and tenon construction • Birch – all stains and glaze • Paint- all colors • Slab Drawer Front • Partial Overlay • Raised Veneer Center Panel TM Durham PureStyle Silver Lining NEW FINISHES Spec Book Page 20 Pretty is as pretty does. Our trend-forward color palette is designed to delight today’s homeowner. Quill Stain Greyhound Paint Trendwatch: True brown finishes continue The new neutral. -

Single Action Wooden Hinge

Plan #1—Wooden hinge, single action There are two types of wooden hinges, a single action hinge (that is in effect a finger joint with a pin through it) and a double action hinge which has two pins. The advantages of the double action hinge are that it will open out 180°, and you can set it in flush with the back of the box. With the single action hinge, it will only open just past 90°, and it can only be rebated into the box to half its thickness, but it is much simpler to make than the double. These plans describe, in detail, making and fitting the single action hinge. See the free download entitled ‘Plan #2—Wooden hinge plans, double action’. They are best made as a small batch with pieces put aside for future use, rather than setting up to make just one pair. For work at this scale you need dial or digital callipers, as a ruler is not accurate enough. You will also need a small solid carbide spiral cutter (3.2mm diameter) and a 2.0mm spur point drill. These items are available from Gifkins Dovetail. Hinge sizes The example in this information sheet describes a hinge for small work—for a box 120mm x 120mm x 60mm. This same hinge can be used on a box 300mm x 250mm x 150mm. There is no reason why the hinge could not be scaled up or down to suit other sized boxes. The actual dimensions will depend on the size of the cutter you use for the finger joints, as the width of the hinge will be an odd whole number multiple of the cutter diameter: e.g. -

SPECIFICATION GUIDE READY-TO-ASSEMBLE KITCHEN and BATH CABINETRY Hdckitchens.Com Ready-To-Assemble Kitchen & Bath Cabinetry 5 Year Limited Warranty

Ships in 2-10 Days All Plywood Construction Soft Close Doors & Drawers 40 Door Styles SPECIFICATION GUIDE READY-TO-ASSEMBLE KITCHEN AND BATH CABINETRY hdckitchens.com Ready-to-Assemble Kitchen & Bath Cabinetry 5 Year Limited Warranty Home Decorators Collection Cabinetry (warrantor) warrants to the original consumer purchaser only, that the Home Decorators Collection branded Ready-to-Assemble (RTA) products will be free from defects in material and workmanship. This warranty is for a period of five years as long as you own the cabinetry and is not transferable to subsequent owners. This warranty does not cover damage resulting from normal wear, accident, misuse or lack of reasonable and necessary maintenance and service; nor does it warranty the improper installation or unauthorized repair, alteration, or modification or defects in the product when the product is installed. This warranty is limited to the repair or replacement of the defective part at the sole discretion of warrantor. Warranty is limited to Home Decorators Collection Cabinetry branded products excluding all electrical components: Excluded items may carry separate warranties as provided directly by the manufacturer of these products. It is our option to provide repair parts or replace with functionally equivalent product. Return of product may be required for replacements. Such repair parts or replacement shall be at warrantor's expense, but customer shall bear all other expenses, including, but not limited to, cost of removal, transportation, re-installation, communication and any special service required by customer such as, overtime labor, etc. Due to the nature of the product, replacement product may vary in color from original purchased product. -

Oregon State Police Tenant Improvement

OREGON STATE CAPITOL ACCESSIBILITY, MAINTENANCE, & SAFETY (CAMS) OREGON STATE POLICE TENANT IMPROVEMENT SRG PARTNERSHIP, INC 03/24/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS DIVISION 1 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS Section 01 11 00 Summary of Work Section 01 26 00 Contract Modification Procedures Section 01 29 00 Payment Procedures Section 01 31 00 Project Coordination Section 01 31 19 Project Meetings Section 01 32 13 Scheduling of Work Section 01 33 00 Submittal Procedures Section 01 35 91 Historic Treatment Procedures Section 01 42 00 References Section 01 45 00 Quality Assurance Section 01 50 00 Temporary Facilities and Controls Section 01 73 29 Cutting and Patching Section 01 74 19 Resource Recovery Section 01 77 00 Closeout Procedures DIVISION 2 EXISTING CONDITIONS Section 02 41 19 Selective Demolition, Salvage, and Protection DIVISION 6 WOOD & PLASTICS Section 06 01 40 Repair and Restoration of Historic Architectural Woodwork Section 06 10 00 Rough Carpentry Section 06 41 00 Architectural Woodwork DIVISION 7 THERMAL AND MOISTURE PROTECTION Section 07 92 00 Joint Sealants DIVISION 8 DOORS AND WINDOWS Section 08 01 14 Repair and Restoration of Historic Wood Doors Section 08 11 13 Metal Doors and Frames Section 08 11 16 Aluminum Frames Section 08 14 16 Wood Doors and Frames Section 08 31 00 Access Doors Section 08 34 00 Special Function Doors Section 08 56 59 Service Window Section 08 71 00 Door Hardware Section 08 74 13 Low-Energy Door Operators Section 08 81 00 Glazing DIVISION 9 FINISHES Section 09 01 21 Repair and Restoration of Plaster Section 09 01 70 Repair -

Aristokraft Specs.Pdf

NEW PRODUCTS ▶ Introduction of and Product Segmentation ▶ Overton PureStyle™ Door Style ▶ VanWyke Thermofoil Door Style ▶ Umber Finish on Birch, Maple, Cherry, Rustic Birch, and Oak ▶ Café Finish on Birch, Maple, Cherry, and Rustic Birch ▶ Rouge Finish on Sinclair Birch ▶ White and Antique Paint on Teagan Maple and Wentworth Maple ▶ 36" High Wall Easy Reach and 42" High Wall Message Center ▶ Additional 18", 21", and 24" High Wall and Refrigerator Wall Cabinets ▶ Drawer Base Cabinets with False Panel for Drop-in Cooktops ▶ 21" Wide Vanity Base and Sink Base Cabinets NEW PRODUCTS INCLUDED IN THIS GUIDE ▶ 32 1/2" High Vanity Sink Base Cabinets ▶ Vanity Wall Sink Bases for Universal Design Applications ▶ Revised Universal Design Cabinets (with 4" Toekick) ▶ Select Construction, APC, and FX Drawer Upgrade Available on Universal Design Cabinets ▶ Additional Toasted Antique Trim Mouldings ▶ Hardware Bar Pulls TABLE OF CONTENTS Product Code Index ..............................................................................2-3 Door Style Numbers ..............................................................................4-6 Common Style Numbers for Finishes ................................................................7 Door Styles .....................................................................................8-16 Core-Plus Details ..................................................................................17 Standard, Select, & All Plywood Construction Options ...........................................18-19 Finish Availability/Finishing -

1898012101.Pdf

"?m '''JSt1 Wjipr " jfHt ( . IP" n"fTT " 1&' For knowing how to T'ie oldest and licst. Advertise to profit Reliable and newsy. Consult tlic patrons of Uniformly leads. The Tlic Evening Bulletin Evening Bulletin Evening Bulletin docs Vol. V. Xo. S17. HONOLULU, II. I., KKIDAY, .JAXUAKY 21, 1S!)S. kick 5 Cunts. THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE strongest export evidence to that 1)R&TII flP MARK KENNEDY of the best salesmen in that line YITILL CARE FOR CHILDREN effect. The whole mat er should I jn this city. L inline health com i be left to the Legislature. polled nun to return to bsn 1" ran j Mr. Sohaofer lliave been look-- ' Cisco for a snort timt. lie caine Receives the Report of the Committee iuuovor the pints nud i find timt Drowned In the Sea OH PapaiKou Last back to the Islands and laloi Central Union Church to Have a Sun- the point of land is included in the made another move to the coast, oh Wharves. wharf. There will not ba over 75 lUesaay Morning, returning about four joars ngo. day Kindergarten. i feet of nilinir, us fully two - thirds For quite- u while he win con- of the proposed wharf is included nected with the "lornl fire depart ' Sad News and Body Brought by And Adjourns Without Making Any Special in what is known ns the Limekiln ment and then entered the steam- While Parents Worship Their Babes Will R- e- point. ship business, first with the Inter-Mau- d Recommendation Further Explanations ot Deceased and ceive Instruction School Opens Mr. -

Built-In Cabinetry Add Charm to Any Home with Customized Storage Cabinets

CABINETS Built-in Cabinetry Add charm to any home with customized storage cabinets BY CHRISTIAN BECKSVOORT ’ve grown used to the pleasure of working solid wood at the makes the space unsuitable for almost anything else. I started with workbench, so it takes some persuasion to get me to leave a rough sketch, consisting of three sections of doors and drawers my shop, haul sheets of plywood, and get on my knees to that would be built in place into a single unit. This built-in navi- scribe along crooked walls. But in my younger days, I built gates the knee wall, but the techniques and order of operations is Imy fair share of kitchen cabinets, commercial fixtures, and built- exactly the same as for a straight built-in. The keys to success are ins. And recently, my most discerning client, my wife, convinced keeping everything plumb and level and having a lot of patience me that we needed a built-in. So out of the shop I went. while you go back and forth between the site and the shop. Early homes tended to lack closets and storage space, so ward- robes and built-ins were common. The Shakers added built-ins Troubleshoot the site wherever possible and turned them into an art form. Most, if not The more sound, plumb, and level the location, the easier your all, the built-ins made by the Shakers were constructed in place. I built-in construction and installation will be. The first thing to did the same, except I used plywood partitions and shelves where do is survey the site. -

Aristokraft Fit Spec Book

Product Specifications | February 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Product Description Index ..........................................................................2 Product Code Index ................................................................................3 Characteristics of Thermofoil ........................................................................4 Cabinet Care/Humidification Effects/Installation Instructions .........................................4 Door Styles ........................................................................................5 Full and Partial Overlay Specifications ...............................................................6 Finish Availability/Finish Descriptions/Door Style Numbers ..........................................7 Ordering Information ...............................................................................8 Construction Specifications .....................................................................10-13 Wall Cabinets ..................................................................................14-20 TABLE OF CONTENTS Wall Cabinets/Straight .......................................................................14-17 Wall Cabinets/Corner ........................................................................18-20 Base Cabinets ..................................................................................21-26 Base Cabinets/Straight ..........................................................................21 Base Cabinets/Sink ...........................................................................22-23