Download (153Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabinet Office Annual Report and Accounts 2007 to 2008

Annual Report and Accounts 2007 – 2008 Making government HC613 work better This document is part of a series of Departmental Reports which along with the Main Estimates 2008–09, the document Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses 2008 and the Supplementary Budgetary Information 2008–09, present the Government’s expenditure plans for 2008–09 onwards, and comparative outturn data for prior years. © Crown Copyright 2008 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 9780 10 295666 5 Cabinet Office Annual Report and Accounts 2007–2008 Incorporating the spring Departmental Report and the annual Resource Accounts For the year ended 31 March 2008 Presented to Parliament by the Financial Secretary to the Treasury pursuant to the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 c.20,s.6 (4) Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 15 July 2008 London: The Stationery Office HC 613 £33.45 Contents 2 Cabinet Office Annual Report and Accounts 2007–08 Pages 4–11 INTRODUCTION -

13 16 03 Edition

June 2009 Issue Five IN PRESS IN PRESS Issue Five Corby Business Academy 1 03 Win a £50 Asda Voucher 13 Spirit of Corby Winner 16 Three Peaks Challenge STUDENT EDITION it’sit’s allall aboutabout ourour studentsstudents andand theirtheir future...future INNOVATIVE PARENTS INFORMATION SCHEME FROM OUR STUDENT EDITOR An innovative Corby Business Academy trial which up with new ways of communicating with parents. saw staff hold a parent information session in a Corby Welcome to the first ever student edition of In the future the plan is to roll the scheme out into In Press. supermarket has been hailed a success. local businesses which employ large numbers of CBA After four issues we thought it was time that A steady stream of parents went along to the first parents. the students picked up their notepads and session held at the Morrisons store in Oakley Road on microphones, so In Press Editor Ms Ashby May 16 to speak to staff about their child’s progress. has kindly handed over her role to myself for Principal Dr Andrew Campbell, said: “This has proved this edition. to be an excellent initiative and has been very helpful for The team of reporters representing each all those parents who came to visit us. It is yet another year group have been busy finding out what way in which CBA is developing a strong presence in the has been going on during this hectic May community and I am delighted that it has been so well term and inside these pages we will bring supported by staff and students alike. -

OWMT Newsletter 2007

The Old Wandsworthians’ Merry Christmas and a Memorial Trust Happy New Year Newsletter No.14. December 2007 HRK Remembered H. Raymond King was Headmaster at Wandsworth School from 1932 to 1963. He suc- ceeded Dr H. Waite who had held the post since 1900. Two headmasters in 63 years sug- gests stability and a devotion to duty. To H. Raymond King duty, diligence and respect were extremely important. The son of a railwayman he attended King Edward V1 School at East Retford; leaving at the age of eighteen to join the army and serve on the Western Front. He rose to the rank of Company Sergeant Major and won the D.C.M, M.M and Croix de Guerre for bravery. In 1919 he went up to Cambridge and ended his time there at the University Training College for Teachers. He had chosen his profession and after teaching at Westminster School and Portsmouth Grammar School he joined Scarborough High School as Headmaster where he developed and introduced the set system we all remember proudly from our days at Wandsworth. He entered the London County Council educational system as headmaster at Forest Hill in 1930 and accepted the post at Wandsworth two years later. King was a visionary who not only introduced the tutorial system, diligence assessments ,the Parents Association and a Careers Master, but was also instrumental in the building H. Raymond King of the fives courts and swimming pool. He pioneered international student exchanges and CBE; DCM; MM; the introduction of Technical Studies alongside the more academic grammar stream. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 504 25 January 2010 No. 29 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 25 January 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 531 25 JANUARY 2010 532 Mr. Coaker: I do not accept that numeracy and House of Commons literacy standards are nowhere near where they should be—a significant rise has taken place in those standards. Monday 25 January 2010 The number of primary school pupils gaining level 4, which is the benchmark that we use, has risen significantly. I mentioned the GCSE results at Battersea Park school, The House met at half-past Two o’clock but the results of other secondary schools up and down the country also show a significant improvement. Are we satisfied with that and do we want to do more? Of PRAYERS course we want to do more, which is why we are introducing one-to-one tuition in primary schools. Such tuition will be carried on into secondary schools and [MR.SPEAKER in the Chair] will be backed up by the resources and investment needed. Oral Answers to Questions Ms Karen Buck (Regent’s Park and Kensington, North) (Lab): Is my hon. Friend aware that the number of pupils obtaining five good GCSEs in Westminster has more than doubled since 1997? Will he join me in CHILDREN, SCHOOLS AND FAMILIES congratulating Martin Tissot and the teachers and pupils at St. -

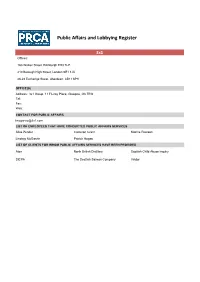

Public Affairs and Lobbying Register

Public Affairs and Lobbying Register 3x1 Offices: 16a Walker Street, Edinburgh EH3 7LP 210 Borough High Street, London SE1 1JX 26-28 Exchange Street, Aberdeen, AB11 6PH OFFICE(S) Address: 3x1 Group, 11 Fitzroy Place, Glasgow, G3 7RW Tel: Fax: Web: CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Ailsa Pender Cameron Grant Katrine Pearson Lindsay McGarvie Patrick Hogan LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED Atos North British Distillery Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry SICPA The Scottish Salmon Company Viridor Public Affairs and Lobbying Register Aiken PR OFFICE(S) Address: 418 Lisburn Road, Belfast, BT9 6GN Tel: 028 9066 3000 Fax: 028 9068 3030 Web: www.aikenpr.com CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Claire Aiken Donal O'Neill John McManus Lyn Sheridan Shane Finnegan LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED Diageo McDonald’s Public Affairs and Lobbying Register Airport Operators Associaon OFFICE(S) Address: Airport Operators Association, 3 Birdcage Walk, London, SW1H 9JJ Tel: 020 7799 3171 Fax: 020 7340 0999 Web: www.aoa.org.uk CONTACT FOR PUBLIC AFFAIRS [email protected] LIST OF EMPLOYEES THAT HAVE CONDUCTED PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES Ed Anderson Henk van Klaveren Jeff Bevan Karen Dee Michael Burrell - external public affairs Peter O'Broin advisor Roger Koukkoullis LIST OF CLIENTS FOR WHOM PUBLIC AFFAIRS SERVICES HAVE BEEN PROVIDED N/A Public Affairs and -

The Share of Funding Received by the East Midlands

House of Commons East Midlands Regional Committee The share of funding received by the East Midlands First Report of Session 2009–10 Volume I HC 104–I House of Commons East Midlands Regional Committee The share of funding received by the East Midlands First Report of Session 2009–10 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 18 March 2010 HC 104–I Published on 26 March 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 East Midlands Regional Committee The East Midlands Regional Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine regional strategies and the work of regional bodies. Current membership Paddy Tipping MP (Labour, Sherwood) (Chair) Mr John Heppell MP (Labour, Nottingham East) Mr Bob Laxton MP (Labour, Derby North) Judy Mallaber MP (Labour, Amber Valley) Sir Peter Soulsby MP Labour, Leicester South) Powers The East Midlands Committee is one of the Regional Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No.152F. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/emid/emid_reports_and_publicat ions.cfm Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are: Adrian Jenner (Clerk); Ian Thomson (Inquiry Manager); Emma Sawyer (Senior Committee Assistant); Ian Blair (Committee Assistant); Anna Browning (Committee Assistant); and Shireen Khattak (NAO Adviser). -

A Minister of State for Social Care

Remedying a sector in crisis: A case for the reinstatement of a Minister of State for Social Care Foreword In 2008, the then Labour Government, led by Gordon Brown, appointed Phil Hope as the Minister of State for Social Care2 – the first time social care had been given such a senior post. The portfolio continued until July 2016, when Prime Minister Theresa May appointed David Mowat in the new role of Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Community Health & Care. No-one who Hft believes that this reshuffle has ‘demoted’ social care to a lower tier of minister, and is a step back in terms of hasn’t been a addressing the challenges facing the social care sector. Parliamentary Under- Secretary of State has any This demotion could not have happened at a more urgent conception of how time for the social care sector: unimportant a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of Local authorities, who commission the majority of State is. adult social care, have seen their budgets cut by central Government. - Andrew Cavendish, Parliamentary Under- Secretary of State 1960-1964.1 Unfunded increases in the National Living Wage will create a £1.3 billion shortfall in funding by 2020. Ongoing legal uncertainties regarding payments for Sleep-In shifts could see the sector face back payments of between £400-600 million. As a charity in the learning disability sector Hft is increasingly supporting individuals with complex needs and challenging behaviours, many of whom require larger, more expensive care packages. Like the population at large, adults with learning disabilities are leading longer, healthier lives, meaning that they will require more support throughout their lifetime. -

Cabinet Member Question Time

Cabinet Cabinet Members’ Reports The following reports from Cabinet Members cover the period from 24th July 2009. Leader of the Council - Mr Henry Smith 1 On 16th September the Leader welcomed Phil Hope MP, Minister for Care Services, to the Maidenbower Day Centre to meet residents from the Crawley area who have taken personal control of their social care support arrangements funded by the County Council through ‘self-directed support’. The Leader highlighted how the County Council was leading on the personalisation agenda through a move from the overly bureaucratic to one that puts vulnerable people at the centre of the care they receive. An innovative website has been set up which enables residents to select and compare care providers across West Sussex. It ties in with the launch of the 2009/10 West Sussex Care Guide which gives information and advice on support and care services for adults across West Sussex. The Leader also took the opportunity to stress how an approach like self-directed support would be even better had the County Council not received such poor financial settlements over the past seven years. 2 On 25th September the Leader, together with the County Chairman, Cabinet Members and Dr Walsh for the Liberal Democrats, met the West Sussex Members of Parliament. The Leaders of the West Sussex borough and district councils were also invited to attend this particular meeting to participate in the main item for discussion which focused on prospects for finance, services and joint working. The meeting also received updates on Children and Young People’s Services, Academies, swine flu, the Comprehensive Area Assessment and the National Park. -

Compact the Text in This Document May Be Reproduced Free of Charge in Any Format Or Media Without Requiring Specific Permission

Publication date: March 2011 © Commission for the Compact The text in this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or media without requiring specific permission. This is subject to it not being used in a derogatory manner or in a misleading context. The source must be acknowledged as copyright of the Commission for the Compact. Contents Foreword 1 Summary 2 Acknowledgements 9 1. Introduction 10 2. Three Compacts: an overview 13 2.1 Original Compact 1998 13 2.2 Refreshed Compact 2009 14 2.3 Renewed Compact 2010 15 3. The Compact in perspective 18 3.1 The Compact in an international context 18 3.2 The Compact in a social policy context 23 4. The development and implementation of the Compact: an overview 27 4.1 Milestones in the development of the Compact 27 4.2 The development and acceptance of the concept of the Compact 33 4.3 Architecture of implementation 36 5. Assessing the impact of the Compact 64 5.1 Awareness 65 5.2 Funding and procurement 72 5.3 Consultation and policy appraisal 89 5.4 Volunteering 100 5.5 Local compacts 117 6. Discussion and conclusions 130 6.1 The “story” so far 130 6.2 Problems of implementation 132 6.3 Was it the right approach? 133 6.4 What next for the Compact? 135 Appendix 1: List of key informants 137 Appendix 2: Undertakings under the Original, Refreshed and Renewed 138 Compacts Appendix 3: Summary of Compact Joint Action Plans 164 Appendix 4: Statement of Support for the Renewed Compact 182 by Sir Bert Massie CBE, Commissioner for the Compact This study, a summative evaluation of the Compact, reviews the origins and effectiveness of the Compact as a policy instrument, assesses the difference it has made to the quality of relationships between the state and the voluntary and community sector, and considers its future prospects. -

Four New Labour & Co-Operative Mps Make History

Party Support Mailing December 2012 NATIONAL NEWS Please find below the latest news from Parliament, our national campaigns, the Co-operative Councils Network and more. Please circulate to your members or include this in your local newsletters. You can find all the latest news and opinions from the Co-operative Party at www.party.coop. Four new Labour & Co-operative MPs make history Excellent by-election results mean that there are a record 32 Labour & Co-operative Members of Parliament, as Andy Sawford, Lucy Powell, Stephen Doughty and Steve Reed join the Parliamentary Group. Manchester Central was the first of three by-elections on 15 November to declare its result, bringing the news that Lucy Powell is the new Member of Parliament, a Co-operative MP representing the heart of the UK co-operative movement, including the HQs of the Co-operative Group, Co-op Bank and Co-operatives UK. Next up we heard the news that Stephen Doughty, Head of Oxfam in Wales, was elected in Cardiff South & Penarth to replace outgoing MP and Co-operative Party NEC member Alun Michael. Finally that afternoon came the declaration in Corby, where Andy Sawford took the seat from the Conservatives with a huge swing, representing a Labour Co-operative gain. Two weeks later, Croydon North elected Steve Reed, a pioneer of the Co-operative Councils initiative and the 32nd member of the Co-operative group of MPs. Thirty two Co-operative Members of Parliament represents the Party’s highest ever number. Karin Christiansen, General Secretary of the Co-operative Party, said: “It is fantastic news that these three great new MPs are joining the Co-operative Party’s Parliamentary Group. -

After Thirty Years, the UK Again Faces a Referendum Tony Blair Surprised Everyone When He Negating the Need for a Referendum

The Constitution Unit Bulletin Issue 27 Monitor June 2004 After Thirty Years, the UK again faces a Referendum Tony Blair surprised everyone when he negating the need for a referendum. What announced in April that the public would be has changed to alter the Government’s consulted in a referendum over whether or stance? It is not the nature of the EU not to accept the new European constitution. constitution itself. True, some commentators The timing of the referendum is unclear, argue that the constitution does extend although it is likely that the issue will be put to European integration and involves a further the people following the next general transfer of sovereignty. In that case, a election, widely anticipated for spring or referendum would be a perfectly proper con- summer 2005. The Government will provide stitutional recourse, as with the devolution for a referendum in the Bill being presented referendums seven years ago. But if this to ratify the constitution, expected in the next argument is accepted, why has the parliamentary session. The responsibility for referendum been granted only now? And why deciding the wording of the question put to was this constitutional doctrine absent in voters will rest with ministers, although the 1986 and 1992 when the Single European Act Electoral Commission will advise on the and Maastricht Treaties were ratified, in both neutrality and intelligibility of the wording. The cases by parliament with no reference to a Commission will also be responsible for popular vote? designating, and providing public funding for, It is difficult to argue that the decision to hold the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ campaign groups. -

November 2009.Doc Date: 14 December 2009 11:40:00

From: Vivek Bhardwaj To: Vivek Bhardwaj Subject: NLGN Policy Round Up November 2009.doc Date: 14 December 2009 11:40:00 November 2009 This month saw the venerable tradition of the Queen’s Speech announcing the Government’s legislative programme for the forthcoming session. The proposed Bills were inevitably viewed through the prism of an imminent General Election, and there was scepticism about how much could actually be enacted in time. Nonetheless, there were some interesting implications for local government which will require further examination. For example, we saw a duty on local authorities to deal with child poverty, and an Equality Bill which will see a public sector duty to reduce gap between rich and poor and to use commissioning to tackle inequality. There was also a Children Schools and Families Bill which pledges to guarantee school entitlements to children and their parents and a Crime and Security Bill which sees mandatory parenting assessment to accompany asbos. Other measures of interest to local government included the Flood and Water Management Bill and the Digital Economy Bill on digital infrastructure. The Personal Care at Home Bill will implement the move towards a National Care Service. 1.Political David Cameron has outlined a new policy focus on tackling the benefits trap. 27 October: Click Here In a keynote speech to the National Housing Federation, Shadow Housing Minister Grant Shapps is to announce plans to give social tenants the chance to move around the country for the first time. 9 November: Click Here Radical new powers will be given to local residents to protect community assets from closure and allow local people to take over the running of public buildings and community assets, Conservatives announced today.