Chlorine in Drinking-Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consumer Confidence Report for 2012

City of Oregon Water Treatment Plant 2012 Water Quality Report The Oregon Water Treatment Plant’s drinking water continues to surpass all federal and state drinking-water standards. This is the fifthteenth annual report on the quality of water delivered by the City of Oregon. It meets the federal Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requirement for “Consumer Confidence Reports”. Safe water is vital to our community. We have a current, unconditioned license to operate our water system. Please read this report carefully and, if you have any questions, call the numbers listed below. Serving You With EXCELLENT Water Quality and Supply Is Our GOAL If we can further assist in answering your questions regarding the water plant or any other water treatment issues, please call Doug Wagner, Superintendent of Water Treatment at 419-698-7123, between the hours of 7:30 AM and 4:00 PM weekdays or on the web at: www.oregonohio.org and follow the links to “The Departments”, then to “The Utilities” and click on “The Water Plant” for our web page and E-mail link. All contract or monetary decisions concerning the water plant are made at city council meetings held the second and fourth Mondays at 8:00 PM in Oregon Council Chambers. Meeting agendas are posted in the municipal building main hallway by the main door and also by following the link to “The City Council” on the city’s web site; www.oregonohio.org This buoy marked the intake structure in Lake Erie when the Plant was built in 1962 and is now on display at the Water Plant. -

Chemical Warfare Agent (CWA) Identification Overview

Physicians for Human Rights Chemical Warfare Agent (CWA) Identification Overview Chemical Warfare Agent Identification Fact Sheet Series Table of Contents This Chemical Warfare Agent (CWA) Identification Fact Sheet is part 2 Physical Properties of a Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) series designed to fill a gap in 2 VX (Nerve Agent) 2 Sarin (Nerve Agent) knowledge among medical first responders to possible CWA attacks. 2 Tabun (Nerve Agent) This document in particular outlines differences between a select 2 BZ (Incapacitating Agent) group of vesicants and nerve agents, the deployment of which would 2 Mustard Gas (Vesicant) necessitate emergency medical treatment and documentation. 3 Collecting Samples to Test for Exposure 4 Protection PHR hopes that, by referencing these fact sheets, medical professionals 5 Symptoms may be able to correctly diagnose, treat, and document evidence of 6 Differential Diagnosis exposure to CWAs. Information in this fact sheet has been compiled from 8 Decontimanation 9 Treatment publicly available sources. 9 Abbreviations A series of detailed CWA fact sheets outlining in detail those properties and treatment regimes unique to each CWA is available at physiciansforhumanrights.org/training/chemical-weapons. phr.org Chemical Warfare Agent (CWA) Identification Overview 1 Collect urine samples, and blood and hair samples if possible, immediately after exposure Physical Properties VX • A lethal dose (10 mg) of VX, absorbed through the skin, can kill within minutes (Nerve Agent) • Can remain in environment for weeks -

Chlorine.Pdf

Chlorine 7782-50-5 Hazard Summary Chlorine is a commonly used household cleaner and disinfectant. Chlorine is a potent irritant to the eyes, the upper respiratory tract, and lungs. Chronic (long-term) exposure to chlorine gas in workers has resulted in respiratory effects, including eye and throat irritation and airflow obstruction. No information is available on the carcinogenic effects of chlorine in humans from inhalation exposure. A National Toxicology Program (NTP) study showed no evidence of carcinogenic activity in male rats or male and female mice, and equivocal evidence in female rats, from ingestion of chlorinated water. EPA has not classified chlorine for potential carcinogenicity. Please Note: The main sources of information for this fact sheet are EPA's Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) (2), which contains information on oral chronic toxicity and the RfD, The California Environmental Protection Agency's (CalEPA's) Technical Support Document for the Determination of Noncancer Chronic Reference Exposure Levels (3), and EPA's Drinking Water Criteria Document for Chlorine, Hypochlorous Acid and Hypochlorite Ion (1). Uses Chlorine is a commonly used household cleaner and disinfectant. It is widely used as an oxidizing agent in water treatment and chemical processes. It is also used in the bleaching process of wood pulp in pulp mills. (8) Sources and Potential Exposure Workers may be exposed to chlorine in industries where it is produced or used, particularly in the food and paper industries. In addition, persons breathing air around these industries may be exposed to chlorine. (1) Exposure to chlorine may also occur through drinking water and swimming pool water, where it is used as a disinfectant. -

The City of Fitchburg Public Works Department/Utility Division 2020 Annual Water Quality Report North System PWSID #11302313

The City of Fitchburg Public Works Department/Utility Division 2020 Annual Water Quality Report North System PWSID #11302313 THE MARK OF EXCELLENT SERVICE The City of Fitchburg, Public Works Department/Utility Division, is pleased to present to you the Annual Water Quality Report for 2020. We are committed to providing our customers with safe and reliable drinking water. This commitment demands diligence, foresight, investment, and long-range planning. Monitoring and treatment are key methods by which the City of Fitchburg protects the public water supply. Each year the Utility Division works hard at ensuring your water supply meets the highest of standards established by the State of Wisconsin and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Drinking water in Fitchburg continues to meet or exceed all of the Environmental Protection Agency’s standards. The water quality data contained in this report is based on monitoring results from the 2020 calendar year. FITCHBURG WATER How often is Fitchburg’s water tested? which is more susceptible to surface contamination. Certified staff at the City of Fitchburg and certified Though certain aquifers may be less susceptible than laboratories conducts the following tests: others, all aquifers are susceptible to some degree of Daily: Fluoride contamination. For this reason, it is imperative that Weekly: Chlorine (two times) wellhead protection guidelines are practiced in an Monthly: Bacteriological (25 samples) effort to maintain the quality of water produced by these wells. Additional testing is completed quarterly, annually, and tri-annually based upon the State of Wisconsin What is my water treated with? and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Your water is treated with liquid chlorine at each requirements. -

Protocols for the Chlorination of Drinking Water (For Small to Medium Sized Supplies)

Government of Sudan Federal Ministry of Health Ministry of Water Resources, Irrigation and Electricity Protocols for the chlorination of drinking water (for small to medium sized supplies) 31 Dec 2017 1 Contents Contents ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Acronyms .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Glossary of terms.............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Key Facts: Chlorination ....................................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Why chlorinate? ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Purpose, scope, limitations and structure .............................................................................................................. 6 2.2.1 Purpose of this document -

Nerve Gas in Public Water

If nerve gases, incidentally or accidentally, contaminate public water supplies, the choice of methods for detection and decontamination will be crucial. Satisfactory methods for Sarin and Tabun are assured. Nerve Gas in Public Water By JOSEPH EPSTEIN, M.S. W ATER WORKS ENGINE-ERS, alert Even the highly toxic and vesicant lewisite, to the hazards of radiological, biologi- when viewed in this light, presents little hazard cal, and chemical warfare agents, must be con- as a water contaminant. Lewisite hydrolyzes cerned primarily, among the chemicals, with almost instantaneously in water to the mildly the nerve gases. vesicant oxide. The toxicity of the oxide is Many other chemical agents, because of in- apparently due to its trivalent arsenic content, trinsically low toxicity if admitted orally, or be- which may be oxidized with ease by chlorine cause of rapid hydrolysis to relatively nontoxic or other oxidizing agents to the less toxic pen- products, are unlikely to appear in hazardous tavalent state. In fact, trivalent arsenic be- concentrations in a large volume of water. For comes converted to the pentavalent state upon example, consider hydrogen cyanide and cyan- standing in water. ogen chloride, extremely toxic if inhaled. It If water containing lewisite is chlorinated would take 1 ton of either, uniformly dissolved according to standard procedures for bacterial in a 10-million-gallon reservoir, to reach a con- purification and is used for not more than 1 centration of 25 p.p.m. This concentration in week to avoid possible cumulative effects, as water is considered physiologically tolerable much as 20 p.p.m. -

Reclaimed Water

Dear Customer Water Quality Drinking Water Sources We are pleased to present this year’s Annual Water Quality Operators from the City of Alamogordo Water Treatment The City's water comes from several sources, depending on Report (Consumer Confidence Report) as required by the Safe division regularly collect and test water samples from reser- seasonal and situational demands and the amount each Drinking Water Act (SDWA). This report is designed to pro- voirs and designated sampling points throughout the system can produce. The primary source comes from a system of vide details about where your water comes from, what it to ensure the water delivered to you meets or exceeds feder- spring compounds, infiltration galleries and stream diver- contains, and how it compares to standards set by regulatory al and state drinking water standards. In 2018, we conducted sions in the Fresnal and La Luz Canyon systems. The water agencies. This report is a snapshot of last year’s water quality. more than 2800 drinking water tests in collected from Este informe contiene informacion muy importante sobre la the transmission and distribution systems. these areas is calidad de su agua potable. Por favor lea este informe o co- This in addition to our extensive treat- piped to the muniquese con alguien que pueda traducer la informacion. ment process control monitoring per- City's 188 mil- formed by our certified operators and lion gallon raw Contaminants and Regulations online instrumentation. storage and The Susceptibility Analysis reveals that treatment The sources of drinking water (both tap water and bottled the utility is well maintained and operat- facility in La water) include rivers, lakes, oceans, streams, ponds, reser- ed, and the sources of drinking water are Luz. -

Compatibility of Material and Electronic Equipment with Methyl Bromide and Chlorine Dioxide Fumigation

EPA/600/R-12/664 | October 2012 | www.epa.gov/ord Compatibility of Material and Electronic Equipment with Methyl Bromide and Chlorine Dioxide Fumigation Assessment and Evaluation Report Offi ce of Research and Development National Homeland Security Research Center EPA 600-R-12-664 Compatibility of Material and Electronic Equipment with Methyl Bromide and Chlorine Dioxide Fumigation Assessment and Evaluation Report National Homeland Security Research Center Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Research Triangle Park, NC 27711 ii Disclaimer The United States Environmental Protection Agency, through its Office of Research and Development’s National Homeland Security Research Center, funded and managed this investigation through EP-C-09- 027 WA 2-58 with ARCADIS U.S., Inc. This report has been peer and administratively reviewed and has been approved for publication as an Environmental Protection Agency document. It does not necessarily reflect the views of the Environmental Protection Agency. No official endorsement should be inferred. This report includes photographs of commercially available products. The photographs are included for purposes of illustration only and are not intended to imply that EPA approves or endorses the product or its manufacturer. Environmental Protection Agency does not endorse the purchase or sale of any commercial products or services. Questions concerning this document or its application should be addressed to: Shannon Serre, Ph.D. National Homeland Security Research Center Office of Research and Development (E-343-06) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 109 T.W. Alexander Dr. Research Triangle Park, NC 27711 (919) 541-3817 [email protected] iii Acknowledgments Contributions of the following individuals and organizations to the development of this document are gratefully acknowledged. -

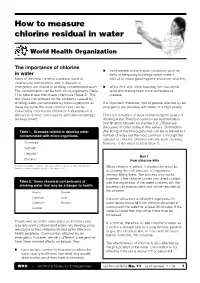

How to Measure Chlorine Residual in Water

How to measure chlorine residual in water World Health Organization The importance of chlorine force people to live in poor conditions such as in water tents or temporary buildings which make it Many of the most common diseases found in difficult to retain good hygiene practices; and they traumatized communities after a disaster or emergency are related to drinking contaminated water. affect their diet, often lowering their nutritional The contamination can be from micro-organisms (Table level and making them more vulnerable to 1) or natural and man made chemicals (Table 2). This disease. fact sheet concentrates on the problems caused by drinking water contaminated by micro-organisms as It is important, therefore, that all people affected by an these are by far the most common and can be emergency are provided with water of a high quality. reduced by chlorination. Chemical contamination is difficult to remove and requires specialist knowledge There are a number of ways of improving the quality of and equipment. drinking water. The most common are sedimentation and filtration followed by disinfection. (These are discussed in other notes in this series). Disinfection Table 1. Diseases related to drinking water (the killing of harmful organisms) can be achieved in a contaminated with micro-organisms number of ways but the most common is through the addition of chlorine. Chlorine will only work correctly, Diarrhoea* however, if the water is clear (Box 1). Typhoid* Hepatitis* Box 1. Cholera* How chlorine kills *Contaminated water is not the only cause of these diseases; water quantity, poor When chlorine is added, it purifies the water by sanitation and poor hygiene practices also play a role destroying the cell structure of organisms, thereby killing them. -

Physical-Chemical Treatment and Disinfection of A

PHYSICAL-CHEMICAL TREATMENT AND DISINFECTION OF A LANDFILL LEACHATE by Victor B. Bjorkman B.A.Sc., University of British Columbia, 1951 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF APPLIED SCIENCE in The Faculty of Graduate Studies C The Department of Civil Engineering) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standards THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1979 Victor Bernhard Bj orkman In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my permission. Victor B. Bjorkman Department of Civil Engineering The University of British Columbia 2075 Westbrook Place Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1W5 Canada ii ABSTRACT Water, flowing through beds of refuse in a sanitary landfill, will leach organic and inorganic substances from the fill. These leached substances may be a source of pollution for receiving surface or ground waters. The leachate, before it is diluted by the receiving water, can usually be classed as a very strong waste water; that is, the levels of the waste water parameters COD, Suspended Solids, low dissolved oxygen and turbidity are many times those found in normal, municipal waste water. Added to these foregoing parameters are possible high levels of toxic chemicals and metals. -

Qt4p41x6ph.Pdf

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Rate constants for the reactions of chlorine atoms with a series of unsaturated aldehydes and ketones at 298 K: structure and reactivity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4p41x6ph Journal Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 4(10) ISSN 14639076 14639084 Authors Wang, Weihong Ezell, Michael J Ezell, Alisa A et al. Publication Date 2002-05-01 DOI 10.1039/b111557j Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California View Article Online / Journal Homepage / Table of Contents for this issue PCCP Rate constants for the reactions of chlorine atoms with a series of unsaturated aldehydes and ketones at 298 K: structure and reactivity Weihong Wang, Michael J. Ezell, Alisa A. Ezell, Gennady Soskin and Barbara J. Finlayson-Pitts* Department of Chemistry, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-2025. E-mail: bjfi[email protected]; Fax: 949 824-3168; Tel: 949 824-7670 Received 2nd January 2002, Accepted 31st January 2002 First published as an Advance Article on the web 18th April 2002 The kinetics and mechanisms of chlorine atom reactions with the products of organic oxidations in the atmosphere are of interest for understanding the chemistry of coastal areas. We report here the first kinetics measurements of the reactions of atomic chlorine with 4-chlorocrotonaldehyde and chloromethyl vinyl ketone, recently identified as products of the reaction of chlorine atoms with 1,3-butadiene. The reactions with acrolein, methacrolein, crotonaldehyde, methyl vinyl ketone and crotyl chloride were also studied to probe structure- reactivity relationships. Relative rate studies were carried out at 1 atm and 298 K using two different approaches: long path FTIR for the acrolein, methacrolein, crotonaldehyde and methyl vinyl ketone reactions with acetylene as the reference compound, and a collapsible Teflon reaction chamber with GC-FID detection of the organics using n-butane or n-nonane as the reference compounds for the entire series. -

Section 5 – Water Quality and Testing

SECTION 5 – WATER QUALITY AND TESTING Maintaining water quality is a fundamental role in operating an aquatic facility. The objectives of an operator should be to: • Ensure the water is properly disinfected at all times, to prevent transmission of infectious diseases, • Achieve maximum patron comfort, and • Maximise longevity of the facility structure. Whenever an aquatic facility is available for use, the water needs to contain an adequate level of a chemical that can destroy micro-organisms. By far the most common chemical used for disinfection is chlorine. This material has the advantages of being a relatively low cost, highly effective disinfectant that is readily available. However, chlorine is also a highly reactive chemical, which non-selectively combines with nitrogen-rich pollutants in the water, to produce unwanted chemicals known as chloramines. These give the water a characteristic pungent chlorine-like smell, and irritate the eyes and skin of patrons. Chloramines are also known to be less effective disinfectants than free chlorine. High concentrations of chloramines reduce the overall effectiveness of the chlorination process. The chloramine problem is generally worse in heavily patronised facilities, where patrons add large amounts of urea and other nitrogen-rich bodily wastes to the water. A number of technologies are now available to reduce the levels of chloramines in water. Examples include the use of ozone gas, ultraviolet light irradiation, and the addition of non-chlorine oxidising chemicals to the water. The use of these technologies should be considered for indoor aquatic facilities with significant bather numbers. Chlorine also undergoes significant degradation when exposed to sunlight.