Qt1mt6m596.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spies That Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2020 Apr 27th, 9:00 AM - 10:00 AM The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the History Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Lew, Masaki, "The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage" (2020). Young Historians Conference. 19. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2020/papers/19 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Spies that Founded America: How the War for Independence Revolutionized American Espionage Masaki Lew Humanities Western Civilization 102 March 16, 2020 1 Continental Spy Nathan Hale, standing below the gallows, spoke to his British captors with nothing less than unequivocal patriotism: “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country.”1 American History idolizes Hale as a hero. His bravery as the first pioneer of American espionage willing to sacrifice his life for the growing colonial sentiment against a daunting global empire vindicates this. Yet, behind Hale’s success as an operative on -

The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1966 The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777 Bernard Mason State University of New York at Binghamton Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Mason, Bernard, "The Road to Independence: The Revolutionary Movement in New York, 1773–1777" (1966). United States History. 66. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/66 The 'l(qpd to Independence This page intentionally left blank THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE The 'R!_,volutionary ~ovement in :J{£w rork, 1773-1777~ By BERNARD MASON University of Kentucky Press-Lexington 1966 Copyright © 1967 UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS) LEXINGTON FoR PERMISSION to quote material from the books noted below, the author is grateful to these publishers: Charles Scribner's Sons, for Father Knickerbocker Rebels by Thomas J. Wertenbaker. Copyright 1948 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., for John Jay by Frank Monaghan. Copyright 1935 by the Bobbs-Merrill Com pany, Inc., renewed 1962 by Frank Monaghan. The Regents of the University of Wisconsin, for The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York J 17 60- 1776) by Carl L. Becker, published by the University of Wisconsin Press. Copyright 1909 by the Regents of the University of Wisconsin. -

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge the Following Excerpts Were Prepared by Col

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge The following excerpts were prepared by Col. Benjamin Tallmadge THE SUBJECT OF THIS memoir was born at Brookhaven, on Long Island, in Suffolk county, State of New York, on the 25th of February, 1754. His father, the Rev. Benjamin Tallmadge, was the settle minister of that place, having married Miss Susannah Smith, the daughter of the Rev. John Smith, of White Plains, Westchester county, and State of New York, on the 16th of May, 1750. I remember my grandparents very well, having visited them often when I was young. Of their pedigree I know but little, but have heard my grandfather Tallmadge say that his father, with a brother, left England together, and came tot his country, one settling at East Hampton, on Long Island, and the other at Branford, in Connecticut. My father descended from the latter stock. My father was born at New Haven, in this State, January 1st, 1725, and graduated at Yale College, in the year 1747, and was ordained at Brookhaven, or Setauket, in the year 1753, where he remained during his life. He died at the same place on the 5th of February, 1786. My mother died April 21st, 1768, leaving the following children, viz.: William Tallmadge, born October 17, 1752, died in the British prison , 1776. Benjamin Tallmadge, born February 25, 1754, who writes this memoranda. Samuel Tallmadge, born November 23, 1755, died April 1, 1825. John Tallmadge, born September 19, 1757, died February 24, 1823. Isaac Tallmadge, born February 25, 1762. My honored father married, for his second wife, Miss Zipporah Strong, January 3rd, 1770, by whom he had no children. -

“Extracts from Some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing

1 “Extracts from some Rebel Papers”: Patriots, Loyalists, and the Perils of Wartime Printing Joseph M. Adelman National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow American Antiquarian Society Presented to the Joint Seminar of the McNeil Center for Early American Studies And the Program in Early American Economy and Society, LCP Library Company of Philadelphia, 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia 24 February 2012 3-5 p.m. *** DRAFT: Please do not cite, quote, or distribute without permission of the author. *** 2 The eight years of the Revolutionary War were difficult for the printing trade. After over a decade of growth and increasing entanglement among printers as their networks evolved from commercial lifelines to the pathways of political protest, the fissures of the war dispersed printers geographically and cut them off from their peers. Maintaining commercial success became increasingly complicated as demand for printed matter dropped, except for government printing, and supply shortages crippled communications networks and hampered printers’ ability to produce and distribute anything that came off their presses. Yet even in their diminished state, printers and their networks remained central not only to keeping open lines of communication among governments, armies, and civilians, but also in shaping public opinion about the central ideological issues of the war, the outcomes of battles, and the meaning of events affecting the war in North America and throughout the Atlantic world. What happened to printers and their networks is of vital importance for understanding the Revolution. The texts that historians rely on, from Common Sense and The Crisis to rural newspapers, almanacs, and even diaries and correspondence, were shaped by the commercial and political forces that printers navigated as they produced printed matter that defined the scope of debate and the nature of the discussion about the war. -

FISHKILLISHKILL Mmilitaryilitary Ssupplyupply Hubhub Ooff Thethe Aamericanmerican Rrevolutionevolution

Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 1234 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, fi ndings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Department of the Interior. FFISHKILLISHKILL MMilitaryilitary SSupplyupply HHubub ooff tthehe AAmericanmerican RRevolutionevolution 11776-1783776-1783 “...the principal depot of Washington’s army, where there are magazines, hospitals, workshops, etc., which form a town of themselves...” -Thomas Anburey 1778 Friends of the Fishkill Supply Depot A Historical Overview www.fi shkillsupplydepot.org Cover Image: Spencer Collection, New York Public Library. Designed and Written by Hunter Research, Inc., 2016 “View from Fishkill looking to West Point.” Funded by the American Battlefi eld Protection Program Th e New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1820. Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 5678 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 Fishkill Military Supply Hub of the American Revolution In 1777, the British hatched a scheme to capture not only Fishkill but the vital Fishkill Hudson Valley, which, if successful, would sever New England from the Mid- Atlantic and paralyze the American cause. The main invasion force, under Gen- eral John Burgoyne, would push south down the Lake Champlain corridor from Distribution Hub on the Hudson Canada while General Howe’s troops in New York advanced up the Hudson. In a series of missteps, Burgoyne overestimated the progress his army could make On July 9, 1776, New York’s Provincial Congress met at White Plains creating through the forests of northern New York, and Howe deliberately embarked the State of New York and accepting the Declaration of Independence. -

Here, a Single Source Is the Only Witness

The Spy Who Never Was The Strange Case of John Honeyman and Revolutionary War Espionage Alexander Rose sion so gravely threaten the John Honeyman is famed as Revolution’s survival. the secret agent who saved George Washington and the The problem is, John Honey- Continental Army during the man was no spy—or at least, dismal winter of 1776/77. At a not one of Washington’s. In this time when Washington had suf- essay I will establish that the fered an agonizing succession of key parts of the story were defeats at the hands of the Brit- The problem is, John invented or plagiarized long “ ish, it was Honeyman who after the Revolution and, Honeyman was no brought the beleaguered com- through repetition, have spy.…Key parts of his mander precise details of the become accepted truth. I exam- story were invented…and Hessian enemy’s dispositions at ine our knowledge of the tale, through repetition have Trenton, New Jersey. assess the veracity of its compo- become accepted truth. nents, and trace its DNA to the Soon afterwards, acting his single story—a piece of family part as double agent, Honey- history published nearly 100 man informed the gullible Col. years after the battle. 1 These Johann Rall, the Hessian com- historical explorations addition- ” ally will remind modern intelli- mander, that the colonials were in no shape to attack. Washing- gence officers and analysts that ton’s men, he said, were suffer- the undeclared motives of ing dreadfully from the cold and human sources may be as many were unshod. -

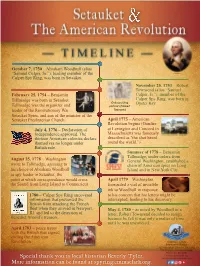

Special Thank You to Local Historian Beverly Tyler. More Information Can Be Found at Spyring.Emmaclark.Org

October 7, 1750 – Abraham Woodhull (alias “Samuel Culper, Sr.”), leading member of the Culper Spy Ring, was born in Setauket. November 25, 1753 – Robert Townsend (alias “Samuel February 25, 1754 – Benjamin Culper, Jr.”), member of the Tallmadge was born in Setauket. Culper Spy Ring, was born in Only surviving Oyster Bay. Tallmadge was the organizer and portrait of Robert leader of the Revolutionary War Townsend Setauket Spies, and son of the minister of the Setauket Presbyterian Church. April 1775 – American Revolution begins (Gunfire July 4, 1776 – Declaration of at Lexington and Concord in Independence approved. The Massachusetts was famously thirteen American colonies declare described as "the shot heard themselves no longer under round the world.”) British rule. Summer of 1778 – Benjamin Tallmadge, under orders from August 25, 1778 – Washington General Washington, established a wrote to Tallmadge, agreeing to chain of American spies on Long his choice of Abraham Woodhull Island and in New York City. as spy leader in Setauket, the point at which correspondence would cross April 1779 – Washington the Sound from Long Island to Connecticut. forwarded a vial of invisible ink to Woodhull in response 1780 – Culper Spy Ring uncovered to his concern that his letters might be information that prevented the intercepted, leading to his discovery. British from attacking the French fleet when they arrived in Newport, May 4, 1780 – as noted by Woodhull in a RI. and led to the detection of letter, Robert Townsend decided to resign Benedict Arnold’s treason. because he felt it was only a matter of time until he was uncovered. -

Coventry Birthplace of Nathan Hale

Historic Coventry is the gateway to Northeast Connecti- In its aim to cherish history, This town is ideal for all ages. Patriots cut’s Quiet Corner. Spread over 37 square miles of Coventry honors its heroes. Park and Lake Wangumbaug are family Welcome woods and old farmlands, our town of 12,500 offers The Vietnam Veteran’s favorites. Patriot’s Park on Lake Street historic sites, farms, antique and specialty shops, public Memorial located on the is an excellent area for retreats and beaches, delicious restaurants, cozy bed-and-breakfast Veteran’s Memorial Green family events, with a guarded beach for to inns, a state boat launch, and an acclaimed farmers’ mar- on Lake Street, honors the swimming, playground, picnic area, ket. 612 Connecticut military personnel who gave their life Community Center and band shell for during the conflict. summer concerts. Lake Wangumbaug Coventry, incorporated in is a popular destination for fishing, Coventry 1712, boasts a wealth of his- History goes hand-in-hand boating, and water sports. Visitors and tory that is rooted in the hero- with agriculture in Coventry. residents can soak up the sunshine outdoors at Coventry’s ic life and death of Connecti- The plethora of farms and two 18-hole golf courses or the several walking trails cut’s state hero, Nathan Hale. local businesses highlight throughout town. His patriotism during the Coventry’s agricultural herit- American Revolution is cele- age. From the locally- brated at several events held throughout the year at Hale produced wines at Cassidy Homestead, the birthplace of Nathan Hale. The Hale For more information on Coventry Homestead, built in 1776, is now an operating museum Hill Vineyard to the organic herbs at Topmost Herb Farm, and its surrounding region, stop by educating visitors from near and far about the famous Coventry covers it all. -

Benjamin Tallmadge Trail Guide.P65

Suffolk County Council, BSA The Benjamin Tallmadge Historic Trail Suffolk County Council, BSA Brookhaven, New York The starting point of this Trail is the Town of Brookhaven parking lot at Cedar Beach just off Harbor Beach Road in Mount Sinai, NY. Hikers can be safely dropped off at this loca- tion. 90% of this trail follows Town roadways which closely approximate the original route that Benjamin Tallmadge and his contingent of Light Dragoons took from Mount Sinai to the Manor of St. George in Mastic. Extreme CAUTION needs to be observed on certain heavily traveled roads. Some Town roads have little or no shoulders at all. Most roads do not have sidewalks. Scouts should hike in a single line fashion facing the oncoming traffic. They should be dressed in their Field Uniforms or brightly colored Class “B” shirt. This Trail should only be hiked in the daytime hours. Since this 21 mile long Trail is designed to be hiked over a two day period, certain pre- arrangements must be made. The overnight camping stay can be done at Cathedral Pines County Park in Middle Island. Applications must be obtained and submitted to the Suffolk County Parks Department. On Day 2, the trail veers off Smith Road in Shirley onto a ser- vice access road inside the Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge for about a mile before returning to the neighborhood roads. As a courtesy, the Wertheim Refuge would like a letter three weeks in advance informing them that you will be hiking on their property. There are no water sources along this hike so make sure you pack enough. -

I Spy Activity Sheet

Annaʻs Adventures I Spy Decipher the Cipher! You are a member of the Culper Ring, an espionage organization from the Revoutionary War. Practice your ciphering skills by decoding the inspiring words of a famous patriot. G Use these keys to decipher the code above. As you can see, the key is made up of two diagrams with letters inside. To decode the message, match the coded symbols above to the letters in the key. If the symbol has no dot, use the first letter in the key. If the symbol has a dot, use the second letter. A B C D E F S T G H I J K L Y Z U V W X M N O P Q R For example, look at the first symbol of the code. The highlighted portion of the key has the same shape as the first symbol. That shape has two letters in it, a “G” and an “H”. The first symbol in the code has no dot, so it must stand for the letter “G”. When you’re done decoding the message, try using the key to write messages of your own! Did You Know? Spying was a dangerous business! Nathan Hale, a spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolution, was executed by the British on September 22, 1776. It was then that he uttered his famous last words: “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.” © Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation • P.O. Box 1607, Williamsburg, VA 23187 June 2015 Annaʻs Adventures I Spy Un-Mask a Secret! A spy gave you the secret message below. -

The War for Independence

The War for Independence Main Idea Reading Strategy Reading Objectives After a war lasting several years, the Sequencing As you read about the war • Describe the strategies behind the colonists finally won their independence for independence, complete a time line Northern Campaign. from Great Britain. similar to the one below to record the • Summarize the scope of the war at sea. major battles and their outcomes. Key Terms and Names Section Theme William Howe, guerrilla warfare, Nathan Global Connections Hostility between Hale, Valley Forge, Marquis de Lafayette, 1776 1781 the French and British caused France to Saratoga, letters of marque, John Paul support the colonies. Jones, Charles Cornwallis, Battle of Kings Mountain !1775 !1778 !1781 !1784 1776 1777 1777–1778 1781 1783 Battle of The British surrender Washington camps at Cornwallis surrenders Treaty of Paris Trenton at Saratoga Valley Forge for the winter at Yorktown signed Colonel Henry Beckman Livingston could only watch helplessly the suffering around him. A veteran of several military campaigns, Livingston huddled with the rest of George Washington’s army at its winter quarters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The winter of 1777 to 1778 was brutally cold, and the army lacked food, clothing, and other supplies. Huddled in small huts, soldiers wrapped themselves in blankets and survived on the smallest of rations. Livingston described the army’s plight in a letter to his brother, Robert: “Our troops are in general almost naked and very often in a starveing condition. All my men except 18 are unfit for duty for want of shoes, stockings, and shirts. Poor Jack has been necessitated to make up his blanket into a vest and breeches. -

SOCIAL STUDIES SUGGESTED UNITS and RESOURCES: HISTORIC MOMENTS DRAMATIZED in PEGGY's NARRATIVE Windows Onto Critically Import

SOCIAL STUDIES SUGGESTED UNITS and RESOURCES: HISTORIC MOMENTS DRAMATIZED IN PEGGY’S NARRATIVE Windows onto Critically Important but Less Discussed Aspects of the American Revolution Letters reveal that Peggy was the only one of the famed Schuyler Sisters to be in the right place at the right time to witness and potentially aid the work of her father, Philip Schuyler—as commanding general and war strategist during the Northern Campaign; as George Washington's most trusted spy-master; as the Patriots’ chief negotiator with the Iroquois Confederacy; and as liaison with French troops under Rochambeau. Peggy’s real life story illuminates the fight in upstate New York and oft overlooked elements of the war, such as: 1. The Battle of Saratoga—the Revolution’s most important turning point in terms of convincing the French to ally with us. It was Philip Schuyler’s spies who discovered the Brits’ deadly three-prong invasion strategy; Philip Schuyler who rallied the militia, slowed the British advance, and prepared the Patriots to win their first major victory. https://www.nps.gov/sara/learn/education/classrooms/the-battles-of-saratoga-reading- activity.htm https://www.nps.gov/sara/learn/kidsyouth/upload/SRA_Elementary_v3.pdf https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/93saratoga/93saratoga.htm https://study.com/academy/lesson/battle-of-saratoga-lesson-plan.html http://www.discoveryeducation.com/teachers/free-lesson-plans/the-american- revolution-saratoga-to-valley-forge.cfm http://historyanimated.com/verynewhistorywaranimated/?page_id=319 Lead-up to the battle: Fort Ticonderoga https://www.fortticonderoga.org/education/educators/resources-by-subject 2. Spying and counter-intelligence in our fight against a superior force.