Towards a More Peripatetic Cultural Studies (A Writing Peripatetic; Birmingham; Poetics; Serres Experiment)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

ROBERT WYATT Title: ‘68 (Cuneiform Rune 375) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL

Bio information: ROBERT WYATT Title: ‘68 (Cuneiform Rune 375) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: ROCK “…the [Jim Hendrix] Experience let me know there was a spare bed in the house they were renting, and I could stay there with them– a spontaneous offer accepted with gratitude. They’d just hired it for a couple of months… …My goal was to make the music I’d actually like to listen to. … …I was clearly imagining life without a band at all, imagining a music I could make alone, like the painter I always wanted to be.” – Robert Wyatt, 2012 Some have called this - the complete set of Robert Wyatt's solo recordings made in the US in late 1968 - the ultimate Holy Grail. Half of the material here is not only previously unreleased - it had never been heard, even by the most dedicated collectors of Wyatt rarities. Until reappearing, seemingly out of nowhere, last year, the demo for “Rivmic Melodies”, an extended sequence of song fragments destined to form the first side of the second album by Soft Machine (the band Wyatt had helped form in 1966 as drummer and lead vocalist, and with whom he had recorded an as-yet unreleased debut album in New York the previous spring), was presumed lost forever. As for the shorter song discovered on the same acetate, “Chelsa”, it wasn't even known to exist! This music was conceived by Wyatt while off the road during and after Soft Machine's second tour of the US with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, first in New York City during the summer of 1968, then in the fall of that year while staying at the Experience's rented house in California, where he was granted free access to the TTG recording facility during studio downtime. -

FORGAS BAND PHENOMENA Title: ACTE V (Cuneiform Rune 332/333)

Bio Information: FORGAS BAND PHENOMENA Title: ACTE V (Cuneiform Rune 332/333) Cuneiform promotion dept.: tel (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 Email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com [press & world radio]; radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com [North American radio] www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / JAZZ-FUSION / JAZZ-ROCK "Since his comeback in the 90s with Forgas Band Phenomena, drummer, bandleader and composer Patrick Forgas ups the ante with each new release...and they just keep getting better and better like fine wine. ...This band flows smoothly between beautifully layered melodic structures into tasty rave ups...equal parts of jazz and rock, with a healthy injections of orchestral brilliance. ...a captivating and spellbinding journey." – Exposé "The Forgas Band Phenomena…blurs idiomatic considerations so extensively they render stylistic definitions irrelevant. No one can accuse…Patrick Forgas of being tame or conservative in his writing and arrangements. ...captivating." – Jazz Times "those...who grew up on the Return to Forever / Mahavishnu Orchestra / Weather Report strain of modern jazz...will love this group. ...The distinct Euro edge of classical Canterbury art rock minus the abject self-indulgence…extremely listenable music that keeps nostalgia to a minimum. ...terrific music made by a wonderful band that cannot be a trade secret for too much longer. Vive la Forgas!" – All Music Guide Composer/drummer Patrick Forgas has been hailed as “the French answer to the Canterbury scene” ever since his debut 1977 release Cocktail (recorded with members of Magma and Zao). Since the late 1990s, as leader of the Forgas Band Phenomena, he has helped ignite interest in Canterbury-infused jazz-rock among a new generation of young French jazz musicians and fans. -

June 2019 New Releases

June 2019 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 79 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 13 FEATURED RELEASES Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 44 YEASAYER - TOMMY JAMES - STIV - EROTIC RERUNS ALIVE NO COMPROMISE Non-Music Video NO REGRETS DVD & Blu-ray 49 Order Form 90 Deletions and Price Changes 85 800.888.0486 THE NEW YORK RIPPER - THE ANDROMEDA 24 HOUR PARTY PEOPLE 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 (3-DISC LIMITED STRAIN YEASAYER - DUKE ROBILLARD BAND - SLACKERS - www.MVDb2b.com EDITION) EROTIC RERUNS EAR WORMS PECULIAR MVD SUMMER: for the TIME of your LIFE! Let the Sunshine In! MVD adds to its Hall of Fame label roster of labels and welcomes TIME LIFE audio products to the fold! Check out their spread in this issue. The stellar packaging and presentation of our Lifetime’s Greatest Hits will have you Dancin’ in the Streets! Legendary artists past and present spotlight June releases, beginning with YEASAYER. Their sixth CD and LP EROTIC RERUNS, is a ‘danceable record that encourages the audience to think.’ Free your mind and your a** will follow! YEASAYER has toured extensively, appeared at the largest festivals and wowed those audiences with their blend of experimental, progressive and Worldbeat. WOODY GUTHRIE: ALL STAR TRIBUTE CONCERT 1970 is a DVD presentation of the rarely seen Hollywood Bowl benefit show honoring the folk legend. Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Odetta, son Arlo and more sing Woody home. Rock Royalty joins the hit-making machine that is TOMMY JAMES on ALIVE!, his first new CD release in a decade. -

Canterbury Sound’ Andy Bennett UNIVERSITY of SURREY

Music, media and urban mythscapes: a study of the ‘Canterbury Sound’ Andy Bennett UNIVERSITY OF SURREY In this article I examine how recent developments in media and technology are both re-shaping conventional notions of the term ‘music scene’ and giving rise to new perceptions among music fans of the relationship between music and place. My empirical focus throughout the article is the ‘Canterbury Sound’, a term originally coined by music journalists during the late 1960s to describe the music of Canterbury1 jazz-rock group the Wilde Flowers, and groups subsequently formed by individual members of the Wilde Flowers – the most well known examples being Caravan, Hatfield and the North and Soft Machine (see Frame, 1986: 16; Macan, 1997; Stump, 1997; Martin, 1998), and a number of other groups with alleged Canterbury connections. Over the years a range of terms, for example ‘Motown’, the ‘Philadelphia Sound’ and, more recently, the ‘Seattle Sound’, have been used as a way of linking musical styles with particular urban spaces. For the most part, however, these terms have described active centres of production for music with a distinctive ‘sound’. In contrast, however, in its original context the Canterbury Sound was a rather more loosely applied term, the majority of groups and artists linked with the Canterbury Sound being London-based and sharing little in the way of a characteristic musical style. Since the mid-1990s, however, the term ‘Canterbury Sound’ has acquired a very different currency as a new generation of fans have constructed a discourse of Canterbury music that attempts to define the latter as a distinctive ‘local’ sound with character- istics shaped by musicians’ direct experience of life in the city of Canterbury. -

The History of Rock Music: 1966-1969

The History of Rock Music: 1966-1969 Genres and musicians of the Sixties History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Canterbury 1968-73 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The Canterbury school of British progressive-rock (one of the most significant movements in the history of rock music) was born in 1962 when Hugh Hopper, Robert Wyatt, Kevin Ayers, Richard Sinclair and others formed the Wilde Flowers. Wyatt, Ayers, Hopper and their new friends Daevid Allen and Mike Ratledge formed the Soft Machine; whereas Sinclair and the others went on to form Caravan. Soft Machine (103), one of the greatest rock bands of all times, started out with albums such as Volume Two (mar 1969 - apr 1969) that were inspired by psychedelic-rock with a touch of Dadaistic (i.e., nonsensical) aesthetics; but, after losing Allen and Ayers, they veered towards a personal interpretation of Miles Davis' jazz-rock on Three (may 1970 - jun 1970), their masterpiece and one of the essential jazz, rock and classical albums of the 1970s. Minimalistic keyboards a` la Terry Riley and jazz horns highlight three of the four jams (particularly, Hopper's Facelift). The other one, Moon In June, is Wyatt's first monumental achievement, blending a delicate melody, a melancholy atmosphere and deep humanity. -

L'école De Canterbury

AYMERIC LEROY L’ÉCOLE DE CANTERBURY le mot et le reste 2016 CANTERBURY TALES PRÉFACE PAR JONATHAN COE Tout commence, comme pour tant de mélomanes ayant grandi dans l’Angleterre des années soixante-dix, avec John Peel. Son émission de radio, diffusée en fin de soirée cinq fois par semaine, est celle qu’il faut écouter impérativement si l’on veut entendre des musiques trop étranges, originales, intelligentes, bizarres voire franchement dérangées pour être diffusées pendant la journée sur les ondes de la BBC. À la fin de la décennie, il sera le premier à consacrer l’essentiel de son émission au punk rock ; et dans les années quatre-vingt, il se fera le chantre de groupes comme The Fall ou les Smiths. Mais durant la première moitié des seventies, son émission fait la part belle aux musiques dites « progres- sives », bien qu’il ne fasse pas mystère de son aversion pour ceux des groupes en question qui s’égaraient dans le boursouflé ou l’excès de sérieux. Fin 1976, un groupe du nom de Caravan publie une compilation intitulée Canterbury Tales, à laquelle Peel consacre l’essentiel d’une de ses émissions. L’un des premiers titres qu’il passe ce soir- là, « Golf Girl », retient d’emblée mon attention. C’est une pop song, très accrocheuse, mais il y a un côté pastiche, parodie. Les paroles sont étranges, un peu idiotes (il y est notamment question d’un orage de balles de golf), mais aussi empreintes d’une fantaisie surréaliste fortement réminiscente de Lewis Carroll. Comme j’aime beaucoup cette chanson, je profite d’une après- midi de shopping à Birmingham avec mes parents le week- end suivant pour acheter le fameux double album. -

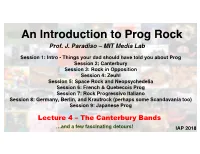

An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof

An Introduction to Prog Rock Prof. J. Paradiso – MIT Media Lab Session 1: Intro - Things your dad should have told you about Prog Session 2; Canterbury Session 3: Rock in Opposition Session 4: Zeuhl Session 5: Space Rock and Neopsychedelia Session 6: French & Quebecois Prog Session 7: Rock Progressivo Italiano Session 8: Germany, Berlin, and Krautrock (perhaps some Scandavania too) Session 9: Japanese Prog Lecture 4 – The Canterbury Bands …and a few fascinating detours! IAP 2018 The City of Canterbury London Up Here An amazingly creative bunch of emerging musicians hung out at Robert Wyatt’s House & environs in the mid 60s Memories Brian & Hugh Hopper, Richard Sinclair, Kevin Ayers formed The Wilde Flowers in the early 1960s – Daevid Allen, David Sinclair, Richard Coughlin, etc. in the mix too Leading to Soft Machine, Caravan, Gong, and Kevin Ayers solo career Enter Soft Machine! Robert Wyatt, Hugh Hopper, Mike Ratledge (Daevid Allen, Kevin Ayers) Jimi was their colleague, friend, and fan He gave them their sound… We Did It Again Early Soft Machine 1968 1969 Why Are We Sleeping? As Long as he Lies Perfectly Still Hung out and toured with Jimi Hendrix Fuzzbox and pedals on organ are iconic in Canterbury Music Very intense live band Hope for Happiness (Live @ Middle Earth Club) - 1967 Live in France - 1968 Kevin Ayers splits for his solo career 1969 1970 1972 1974 Rheinhardt And Geraldine / Colores Para Dolores (1970) The Confessions Of Doctor Dream: Irreversible Neural Damage (1974) Becoming a (psychedelic) Jazz Band 1970 1971 1972 Last -

Gonzo Weekly #158

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 and vinegar, and then disappeared into the abyss never to be heard of again. There is now't as queer as folk. And in music Dear Friends, Welcome to another issue of this singular little magazine which with this issue is three years old. I am still, as I say quite often these days, surprised by how it has progressed, as well as by the hard work and support of so many of the regular contributors. Peculiarly, I am also surprised by the lack of enthusiasm by various would-be contributors who have approached me to write for the magazine, appeared to be massively enthusiastic and full of good ideas, and what my late father would have called piss 4 "Enough already, thank you very much, now can we just get on with this song?" journalism that old northern aphorism is even more true than it is in life generally, which is telling you something! This week, I have not been particularly well, and so I have spent more time than I would otherwise have done, sitting with Archie the Jack Russell in my favourite armchair with my ipad hooked up via wifi and something called the Apple AirPort (which has nothing to do with aeroplanes) to my hifi, and listening to musical favourites old and new. -

Simon Frith Can Music Progress?

Simon Frith Can Music Progress?... Simon Frith CAN MUSIC PROGRESS? REFLECTIONS ON THE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC Abstract: This paper considers schematically the various discourses through which popular music history is understood. My proposal is that five accounts of musical history (the business model, the musicological model, the socio- logical model, the historical model and the art history model) are commonly deployed in popular music discourse. One implies, superficially at least, that popular music evolves, gets better; four implies that, at least in the longer term, it does not. The concept of ‘progress’ is shown to be problematic. Key words: Popular music; history; progress; progressive rock. Introduction: progressive rock This paper was originally written as the keynote address for an in- ternational cross-disciplinary postgraduate conference entitled ‘Evolu- tions’. My brief was to consider the evolution of popular music, a con- cept which I translated into a question which had often bothered me when I was a practicing rock critic: can popular music be said to pro- gress? ‘Progress’ is an odd term in popular music discourse. The word ‘progressive’ has been deployed in various musical genres – progressive country music, progressive jazz, progressive folk. But as a genre label it has been most significantly used in rock. The Guardian thus headlined its obituary of the musician, Pip Pyle (September 20 2006), “Innovative drummer at the heart of progressive rock”, and suggested that he “encapsulated all that was groundbreaking in British progressive music in the shakeout from the 1960s”. But what is clear in the paper’s account of Pip Pyle’s career – as a member of Hatfield and the North, Gong, National Health and numerous other bands – is that ‘progressive rock’ was not a stage pop music moved through on its way to somewhere else but, rather, describes a particular musical genre, whose popularity was small scale and short lived (and, quite soon, rooted in France and Germany rather than the UK). -

Gonzo Weekly, and Used with the No Matter What Religion You Have, Or Indeed, Whether Photographer’S Permission

2 rapidly going out of the window. Successive governments have done their best to demonise the unemployed and to terrorize those people who are on sickness benefits of one sort or another. The popular conception that people who are too idle to support themselves only have to go to a sympathetic doctor with some made up ailment or other in order to get a lifetime of living high on the hog at the expense of the poor hard working tax payer is completely false, but it is a fallacy which has been promoted to a ridiculous extent by the government and its lackeys in the media. This has got to such a ridiculous extent that I know personally one young man in his twenties who is so severely handicapped that he cannot speak coherently, that he is doubly incontinent, and cannot walk unaided, had his benefit cut off recently and was told he was fit for work. Luckily common sense and some sort of concept of fair play prevailed, but this is only one incident out of many that I could quote. Dear Friends, A friend of mine who is severely dyslexic, has the We are living in strange and disturbing times. I know computer skills of a three-toed sloth, and can only that this is primarily a music magazine, but as afford a 15 year old laptop running Windows XP had intelligent people it is very difficult to ignore the things his benefits stopped purely because he didn’t which are going on around us. understand how to log in to the government jobseekers website which – apparently – does not allow It is very difficult to ignore the behaviour of those who computers running Windows XP to access it. -

L'axe Du Fou / Axis of Madness Press Quotes

EXCERPTS FROM WHAT THE PRESS HAS SAID ABOUT FORGAS BAND PHENOMENA: AXIS OF MADNESS / L'AXE DU FOU 2009 CUNEIFORM (RUNE 282) Line-up: Patrick Forgas (Drums), Igor Brover (Keyboards), Kengo Mochizuki (Bass), Benjamin Violet (guitar), Karolina Mlodecka (violin), Sébastien Trognon (saxes & flute) and Dimitri Alexaline (trumpet & flugelhorn) “French drummer/composer Patrick Forgas does things like make records based on Moisset's philosophic writings (Synchronicité) and write fusion- soaked symphonies epically long (Soleil 12) and majestically winding. That's what it takes to lead a fluctuating unit…easily comparable to Carla Bley at her wily frenetic finest. … … L'Axe du Fou's four tracks benefit from raw-powered freshness… And though rich, this album is sharp, succinct and more streamlined than Forgas's last efforts, more dependent upon intimate rococo intricacies than big-picture blasts. Blame that on the tightly wound compositions whose manias are reined in by Forgas and Mochizuki's insistent rhythms as well on the band's ability to be as somnolent ("La Clef") as it is vigorous ("L'Axe du Fou"). …” - A.D. Amorosi, Jazz Times “… L'Axe du Fou [features] Forgas' most concise and streamlined writing to date, with little in the way of excess or overstatement. While FBP has always been stylistically compared to the British Canterbury scene—and rightly so—in particular with groups like Hatfield and the North, National Health and Phil Miller's In Cahoots, L'Axe du Fou does begin to widen the gap, lending FBP a more singular and distinctive voice. A greater reliance on horns and violin with less on the more conventional guitar-keys-bass-drums line-ups of many Canterbury groups… FBP…even in the more sterile confines of the studio…proves capable of the kind of energy…associated with live performance.