East Village District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago's Neighborhoods

Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago’s Neighborhoods Explore the cultural richness of Chicago’s 77 neighborhoods through Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago’s Neighborhoods in this weekly challenge! Each week explore the history of Chicago’s neighborhoods and the challenges migrants, immigrants, and refugees faced in the city of Chicago. Explore the choices these communities made and the changes they made to the city. Each challenge comes with a short article on the neighborhood history, a visual activity, a read-along audio, a short video, and a Chicago neighborhood star activity. Every week, a new challenge will be posted. The resources for this challenge come from our very own Chicago Literacies Program curriculum with CPS schools. You can read more about the program here https://www.chicagohistory.org/education/chiliteracies/. Introduction Chicago is the third-largest city in the United States. The city is made up of more than 200 neighborhoods and 77 community areas. The boundaries of some neighborhoods and communities are part of a long debate. Chicago neighborhoods and communities are grouped into 3 different areas or sides. The Southside, Northside, and Westside are used to divide the city of Chicago. There is no east side because lake Michigan is east of the city. These three sides surround the city’s downtown area, or the Loop, and have been home to different groups of people. The Southside The Southside of Chicago is geographically the largest of all the sides. Some of the neighborhoods that are part of the Southside include Back of the Yards, Bridgeport, Hyde Park, Kenwood, Beverly, Mount Greenwood and many more. -

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

History of Chicago's Alleys

Living History of Illinois and Chicago® Living History of Illinois and Chicago® – Facebook Group. Digital Research Library of Illinois History® Living History of Illinois Gazette - The Free Daily Illinois Newspaper. Illinois History Store® – Vintage Illinois and Chicago logo products. The History of Chicago's Alleys. Chicago is the alley capital of the country, with more than 1,900 miles of them within its borders. Quintessential expressions of nineteenth-century American urbanity, alleys have been part of Chicago's physical fabric since the beginning. Eighteen feet in width, they graced all 58 blocks of the Illinois & Michigan Canal commissioners' original town plat in 1830, providing rear service access to property facing the 80-foot-wide main streets. Originally Chicago alleys were unpaved, most had no drainage or connection to the sewer system, leaving rainwater to simply drain through the gravel or cinder surfacing. Some heavily used alleys were paved with Belgian wood blocks. Before Belgian block became common, there were many different pavement methods with wildly varying 1 Living History of Illinois and Chicago® Living History of Illinois and Chicago® – Facebook Group. Digital Research Library of Illinois History® Living History of Illinois Gazette - The Free Daily Illinois Newspaper. Illinois History Store® – Vintage Illinois and Chicago logo products. advantages and disadvantages. Because it was so cheap wood block was one of the favored early methods. Chicago street bricks were also used and then alleys were paved over with concrete or asphalt paving. But private platting soon produced a few blocks without alleys, mostly in the Near North Side's early mansion district or in the haphazardly laid-out industrial workingmen's neighborhoods on the Near South Side. -

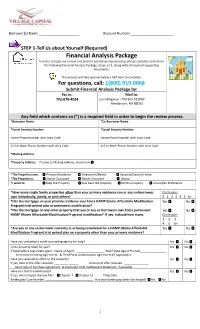

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

sustainability Article Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa Jytte Agergaard * , Susanne Kirkegaard and Torben Birch-Thomsen Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 13, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (T.B.-T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the next twenty years, urban populations in Africa are expected to double, while urban land cover could triple. An often-overlooked dimension of this urban transformation is the growth of small towns and medium-sized cities. In this paper, we explore the ways in which small towns are straddling rural and urban life, and consider how insights into this in-betweenness can contribute to our understanding of Africa’s urban transformation. In particular, we examine the ways in which urbanism is produced and expressed in places where urban living is emerging but the administrative label for such locations is still ‘village’. For this purpose, we draw on case-study material from two small towns in Tanzania, comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, including analyses of photographs and maps collected in 2010–2018. First, we explore the dwindling role of agriculture and the importance of farming, businesses and services for the diversification of livelihoods. However, income diversification varies substantially among population groups, depending on economic and migrant status, gender, and age. Second, we show the ways in which institutions, buildings, and transport infrastructure display the material dimensions of urbanism, and how urbanism is planned and aspired to. Third, we describe how well-established middle-aged households, independent women (some of whom are mothers), and young people, mostly living in single-person households, explain their visions and values of the ways in which urbanism is expressed in small towns. -

Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago During the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 Samuel C. King Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Recommended Citation King, S. C.(2019). Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5418 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 by Samuel C. King Bachelor of Arts New York University, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Sklaroff, Major Professor Mark Smith, Committee Member David S. Shields, Committee Member Erica J. Peters, Committee Member Yulian Wu, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The central aim of this project is to describe and explicate the process by which the status of Chinese restaurants in the United States underwent a dramatic and complete reversal in American consumer culture between the 1890s and the 1930s. In pursuit of this aim, this research demonstrates the connection that historically existed between restaurants, race, immigration, and foreign affairs during the Chinese Exclusion era. -

Village Officers Handbook

OHIO VILLAGE OFFICER’S HANDBOOK ____________________________________ March 2017 Dear Village Official: Public service is both an honor and challenge. In the current environment, service at the local level may be more challenging than ever before. This handbook is one small way my office seeks to assist you in meeting that challenge. To that end, this handbook is designed to be updated easily to ensure you have the latest information at your fingertips. Please feel free to forward questions, concerns or suggestions to my office so that the information we provide is accurate, timely and relevant. Of course, a manual of this nature is not to be confused with legal advice. Should you have concerns or questions of a legal nature, please consult your statutory legal counsel, the county prosecutor’s office or your private legal counsel, as appropriate. I understand the importance of local government and want to make sure we are serving you in ways that meet your needs and further our shared goals. If my office can be of further assistance, please let us know. I look forward to working with you as we face the unique challenges before us and deliver on our promises to the great citizens of Ohio. Thank you for your service. Sincerely, Dave Yost Auditor of State 88 East Broad Street, Fifth Floor, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3506 Phone: 614-466-4514 or 800-282-0370 Fax: 614-466-4490 www.ohioauditor.gov This page is intentionally left blank. Village Officer’s Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Home Rule I. Definition ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 II. -

Reavis High School Curriculum Snapshot/Cover Page for History of Chicago Unit 1: the Physical Setting Unit 2: City on the Make

Reavis High School Curriculum Snapshot/Cover Page for History of Chicago Unit 1: The Physical Setting Chicago's geographic and geological characteristics will be taught in this unit. Students will gain an understanding of 10 how the area's physical characteristics were formed. The evolution of Chicago and the metropolitan area will also Days be discussed. Other topics covered will be Chicago's grid system and how Chicago compares in size to other metropolitan areas in the United States. Unit 2: City on the Make Students will examine Chicago as the crossroads of economic and cultural exchange from prehistoric time to the present. Students will understand how Native 15 Americans, European explorers, and early Americans Days developed Chicago into a hub of economic and cultural activity. Areas of study will include pre-1871, the I &M Canal, development of the railroad, the Chicago Stockyards, and current economic forces. Unit 3: City in Crisis Students will study how conflicting social, economic, and 15 political forces created disorder and forced changes in the Chicago area. Topics included in this unit will be The Days Chicago Fire, The Haymarket Affair, Al Capone and Prohibition, and the 1968 Democratic Convention. Unit 4: Ethnic Chicago Students will gain an overview of how Chicago's communities have developed over ethnic and racial lines. Students will study past and present community 10 settlement patterns and understand forces that have Days caused changes in these patterns. Other topics of study will include the 1919 and 1968 Race Riots, Jane Addams, and the development of the Reavis community. Unit 5: Unique Chicago Students will explore institutions and personalities that are uniquely Chicago. -

Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: a Case Study of Guangzhou

sustainability Case Report Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: A Case Study of Guangzhou Fan Wu 1, Ling-Hin Li 2,* ID and Sue Yurim Han 2 1 Department of Construction Management, School of Civil Engineering and Transportation, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510630, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Real Estate and Construction, Faculty of Architecture, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-2859-2128 Received: 21 May 2018; Accepted: 19 June 2018; Published: 21 June 2018 Abstract: Rapid economic development in China has generated substantial demand for urban land for development, resulting in an unprecedented urbanization process. The expansion of urbanized cities has started to engulf rural areas, making the urban–rural boundary less and less conspicuous in China. Urban encroachment has led to a rapid shrinkage of the rural territory as the rural–urban migration has increased due to better job opportunities and living standards in the urban cities. Urban villages, governed by a rural property rights mechanism, have started to emerge sporadically within urbanised areas. Various approaches, such as state-led, developer-led, or collective-led approaches, to redevelop these urban villages have been adopted with varying degrees of success. This paper uses a case-study framework to analyse the state–market interplay in two very different urban village redevelopment cases in Guangzhou. By an in-depth comparative analysis of the two regeneration cases in Guangzhou, which started within close proximity in terms of geographical location and timing, we are able to shed light on how completely different outcomes may result from different forms of state–market interplay. -

The Shifting of Village Autonomy Concept in Indonesia

THE SHIFTING OF VILLAGE AUTONOMY CONCEPT IN INDONESIA Abstract This research tries to examine comprehensively about the different concepts about village autonomy in Law No. 5 of 1979 and Law No. 6 of 2014. The results supposed to be contributed as scientific journal and other scientific work, which is valuable for scientific improvement in provincial autonomy law. Itsurely could be used by the local governments in Indonesia and hopefully in Asia as a framework to construct a strategic procedure of the village development. This study uses the conceptual approach and analysis approach as methods. The conceptual approach directed to examine the first legal issue related to differ autonomy concept in Law No. 5 of 1979 and Law No. 6 of 2014 while the analytical approach is used for assessing the alignment of the concept of village autonomy in Law No. 6 of 2014 with a constitutional mandate. The results found, there is improvements in the draft of Law No. 6 Year 2014 by increasing the funding source for the village, and guarantee the right to determine her village. A village, in Law No. 6 Year 2014, is possible to switch into a custom village. Keywords: village, village governance, village autonomy I. Introduction Enactment of the Law No. 6 Year 2014, constantly ended the village government setting in Law No. 32 Year 2004,1and a sign of the village model setting within a different law. Such condition had ever occurred in the New Order era by the emerging of Law No. 5 Year 1979 on Village (“Village Law”). This concept of Village Government may cause a lot of problems such as weakening the capacity of the village administration, policy form and the village unique 2. -

The Castle and the Village: the Many Faces of Limited Access

01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 3 1 The Castle and the Village: The Many Faces of Limited Access jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi Access Denied No author in world literature has done more to give shape to the nightmarish challenges posed to access by modern bureaucracies than Franz Kafka. In his novel The Castle, “K.,” a land surveyor, arrives in a village ruled by a castle on a hill (see Kafka 1998). He is under the impression that he is to report for duty to a castle authority. As a result of a bureaucratic mix-up in communications between the cas- tle officials and the villagers, K. is stuck in the village at the foot of the hill and fails to gain access to the authorities. The villagers, who hold the castle officials in high regard, elaborately justify the rules and procedures to K. The more K. learns about the castle, its officials, and the way they relate to the village and its inhabitants, the less he understands his own position. The Byzantine codes and formalities gov- erning the exchanges between castle and village seem to have only one purpose: to exclude K. from the castle. Not only is there no way for him to reach the castle, but there is also no way for him to leave the village. The villagers tolerate him, but his tireless struggle to clarify his place there only emphasizes his quasi-legal status. Given K.’s belief that he had been summoned for an assignment by the authorities, he remains convinced that he has not only a right but also a duty to go to the cas- tle! How can a bureaucracy operate in direct opposition to its own stated pur- poses? How can a rule-driven institution be so unaccountable? And how can the “obedient subordinates” in the village wield so much power to act in their own self- 3 01-7501-1 CH 1 10/28/08 5:17 PM Page 4 4 jorrit de jong and gowher rizvi interest? But because everyone seems to find the castle bureaucracy flawless, it is K. -

Is It Time for New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? a Background Report on Village Incorporation in New York State

Is It Time For New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? A Background Report on Village Incorporation in New York State Lisa K. Parshall January 2020 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Lisa Parshall is a professor of political science at Daemen College in Amherst, New York and a public Photo credit:: Martin J. Anisman policy fellow at the Rockefeller Institute of Government 2 Is It Time for New York State to Revise Its Village Incorporation Laws? Over the past several years, New York State has taken considerable steps to eliminate or reduce the number of local governments — streamlining the law to make it easier for citizens to undertake the process as well as providing financial incentives for communities that undertake consolidations and shared services. Since 2010, the residents of 42 villages have voted on the question of whether to dissolve their village government. This average of 4.7 dissolution votes per year is an increase over the .79 a-year-average in the years 1972-2010.1 The growing number of villages considering dissolution is attributable to the combined influence of declining populations, growing property tax burdens, and the passage of the New N.Y. Government Reorganization and Citizen Empowerment Act (herein after the Empowerment Act), effective in March 2019, which revised procedures to make it easier for citizens to place dissolution and consolidation on the ballot. While the number of communities considering and voting on dissolution has increased, the rate at which dissolutions have been approved by the voters has declined. That is, 60 percent of proposed village dissolutions bought under the provisions of the Empowerment Act have been rejected at referendum (see Dissolving Village Government in New York State: A Symbol of a Community in Decline or Government Modernization?)2 While the Empowerment Act revised the processes for citizen-initiated dissolutions and consolidations, it left the provisions for the incorporation of new villages unchanged.