(Family Drepanididae) Have Received C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convergent Evolution of 'Creepers' in the Hawaiian Honeycreeper

ARTICLE IN PRESS Biol. Lett. 1. INTRODUCTION doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0589 Adaptive radiation is a fascinating evolutionary pro- 1 cess that has generated much biodiversity. Although 65 2 Evolutionary biology several mechanisms may be responsible for such 66 3 diversification, the ‘ecological theory’ holds that it is 67 4 the outcome of divergent natural selection between 68 5 Convergent evolution of environments (Schluter 2000). Whether adaptive 69 6 radiations result chiefly from such ecological speciation, 70 7 ‘creepers’ in the Hawaiian however, remains unclear (Schluter 2001). Convergent 71 8 evolution is often considered powerful evidence for the 72 9 honeycreeper radiation role of adaptive forces in the speciation process 73 (Futuyma 1998), and thus documenting cases where it 10 Dawn M. Reding1,2,*, Jeffrey T. Foster1,3, 74 has occurred is important in understanding the link 11 Helen F. James4, H. Douglas Pratt5 75 12 between natural selection and adaptive radiation. 76 and Robert C. Fleischer1 13 The more than 50 species of Hawaiian honeycree- 77 1 14 Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, National pers (subfamily Drepanidinae) are a spectacular 78 Zoological Park and National Museum of Natural History, 15 Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20008, USA example of adaptive radiation and an interesting 79 16 2Department of Zoology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, system to test for convergence, which has been 80 17 HI 96822, USA suspected among the nuthatch-like ‘creeper’ eco- 81 3Center for Microbial Genetics & Genomics, -

Mt. Tabor Park Breeding Bird Survey Results 2009

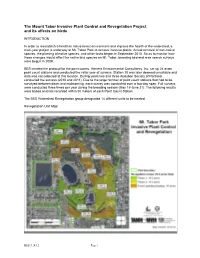

The Mount Tabor Invasive Plant Control and Revegetation Project and its affects on birds INTRODUCTION In order to reestablish a healthier native forest environment and improve the health of the watershed, a multi-year project is underway at Mt. Tabor Park to remove invasive plants. Actual removal of non-native species, the planting of native species, and other tasks began in September 2010. So as to monitor how these changes would affect the native bird species on Mt. Tabor, breeding bird and area search surveys were begun in 2009. BES created the protocol for the point counts. Herrera Environmental Consultants, Inc. set up 24 avian point count stations and conducted the initial year of surveys. Station 10 was later deemed unsuitable and data was not collected at this location. During years two and three Audubon Society of Portland conducted the surveys (2010 and 2011). Due to the large number of point count stations that had to be surveyed between dawn and midmorning, each survey was conducted over a two-day span. Full surveys were conducted three times per year during the breeding season (May 15-June 31). The following results were based on birds recorded within 50 meters of each Point Count Station. The BES Watershed Revegetation group designated 14 different units to be treated. Revegetation Unit Map: BES 3.14.12 Page 1 Point Count Station Location Map: The above map was created by Herrera and shows where the point count stations are located. Point Count Stations are fairly evenly dispersed around Mt. Tabor in a variety of habitats. -

By Mark Macdonald Bsc. Forestry & Environmental Management A

PRE-TRANSLOCATION ASSESSMENT OF LAYSAN ISLAND, NORTH-WESTERN HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, AS SUITABLE HABITAT FOR THE NIHOA MILLERBIRD (ACROCEPHALUS FAMILIARIS KINGI) by Mark MacDonald BSc. Forestry & Environmental Management A Thesis, Dissertation, or Report Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MSc. Forestry in the Graduate Academic Unit of Forestry Supervisor: Tony Diamond, PhD, Faculty of Forestry & Environmental Management, Department of Biology. Graham Forbes, PhD, Faculty of Forestry & Environmental Management, Department of Biology. Examining Board: (name, degree, department/field), Chair (name, degree, department/field) This thesis, dissertation or report is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK 01, 2012 ©Mark MacDonald, 2012 DEDICATION To the little Nihoa Millerbird whose antics, struggles and loveliness inspired the passion behind this project and have taught me so much about what it means to be a naturalist. ii ABSTRACT The critically endangered Nihoa Millerbird (Acrocephalus familiaris kingi), endemic to Nihoa Island, is threatened due to an extremely restricted range and invasive species. Laysan Island once supported the sub-species, Laysan Millerbird (Acrocephalus familiaris familiaris), before introduced rabbits caused their extirpation. A translocation of the Nihoa Millerbird from Nihoa Island to Laysan Island would serve two goals; establish a satellite population of a critically endangered species and restore the ecological role played by an insectivore passerine on Laysan Island. Laysan Island was assessed as a suitable translocation site for the Nihoa Millerbird with a focus placed on dietary requirements. This study showed that Laysan Island would serve as a suitable translocation site for the Nihoa Millerbird with adequate densities of invertebrate prey. -

Downloadable Data Collection

Smetzer et al. Movement Ecology (2021) 9:36 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-021-00275-5 RESEARCH Open Access Individual and seasonal variation in the movement behavior of two tropical nectarivorous birds Jennifer R. Smetzer1* , Kristina L. Paxton1 and Eben H. Paxton2 Abstract Background: Movement of animals directly affects individual fitness, yet fine spatial and temporal resolution movement behavior has been studied in relatively few small species, particularly in the tropics. Nectarivorous Hawaiian honeycreepers are believed to be highly mobile throughout the year, but their fine-scale movement patterns remain unknown. The movement behavior of these crucial pollinators has important implications for forest ecology, and for mortality from avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum), an introduced disease that does not occur in high-elevation forests where Hawaiian honeycreepers primarily breed. Methods: We used an automated radio telemetry network to track the movement of two Hawaiian honeycreeper species, the ʻapapane (Himatione sanguinea) and ʻiʻiwi (Drepanis coccinea). We collected high temporal and spatial resolution data across the annual cycle. We identified movement strategies using a multivariate analysis of movement metrics and assessed seasonal changes in movement behavior. Results: Both species exhibited multiple movement strategies including sedentary, central place foraging, commuting, and nomadism , and these movement strategies occurred simultaneously across the population. We observed a high degree of intraspecific variability at the individual and population level. The timing of the movement strategies corresponded well with regional bloom patterns of ‘ōhi‘a(Metrosideros polymorpha) the primary nectar source for the focal species. Birds made long-distance flights, including multi-day forays outside the tracking array, but exhibited a high degree of fidelity to a core use area, even in the non-breeding period. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

Goldfinches and Finch Food!

A Purple Finch (left) en- Frequently Asked Questions joys Sunflower Hearts and About Finch FOOD: an American goldfinch (right, in winter plumage) B i r d s - I - V i e w munches on a 50/50 blend Q. What do Finches eat? of Sunflower heart chips A. Finches utilize many small grass seeds and and Nyjer Seed . flower seed in nature and are built to shell tiny Frequently Asked Questions seeds easily. At Backyard Bird feeders they will Q. Do Goldfinches migrate in winter? FAQ consume Nyjer Seed (traditionally referred to as A. In much of the US, including the Mid- “thistle” in the bird feeding industry, but now west, Goldfinch are year-round residents. about more correctly referred to as “Nyjer”). They also There are areas of the US that only experi- consume Black Oil sunflower Seed and LOVE ence Goldfinch in the Winter and parts of Goldfinches and Sunflower HEARTS whether whole or in fine northern US and Canada only have them chips. In recent years, more and more backyard during breeding season. Check out the nota- Finch Food! birders are feeding Sunflower hearts (which ble difference between the Goldfinch’s does not have a shell) either alone or combined plumage in the winter and during breeding with the traditional Nyjer seed (which DOES season on the cover of this brochure! Q. What other finches can I see at feeders used by Goldfinch? A. Year-round House Finch as well as non- finch family birds like chickadees, tufted Titmouse, and Downy Woodpecker will en- joy your finch feeder. -

Synonymies for Indigenous Hawaiian Bird Taxa

Part 2 - Drepaninines Click here for Part 1 - Non-Drepaninines The Birds of the Hawaiian Islands: Occurrence, History, Distribution, and Status Version 2 - 1 January 2017 Robert L. Pyle and Peter Pyle Synonymies for Indigenous Hawaiian Bird Taxa Intensive ornithological surveying by active collectors during the latter 1890s led to several classic publications at the turn of the century, each covering nearly all species and island forms of native Hawaiian birds (Wilson and Evans 1899, Rothschild (1900),schild 1900, Bryan 1901a, Henshaw (1902a), 1902a, Perkins (1903),1903). The related but diverse scientific names appearing in these publications comprised the basis for scientific nomenclature for the next half century, but in many cases were modified by later authors using modern techniques to reach a current nomenclature provided in the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) Check-List, and followed (for the most part) at this site. A few current AOU names are still controversial, and more changes will come in the future. Synonymies reflecting the history of taxonomic nomenclature are listed below for all endemic birds in the Hawaiian Islands. The heading for each taxon represents that used in this book, reflecting the name used by the AOU (1998), as changed in subsequent AOU Supplements, or, in a few cases, as modified here based on more recent work or on differing opinions on taxonomic ranking. Previously recognized names are listed and citations included for classic publications on taxonomy of Hawaiian birds, as well as significant papers that influenced the species nomenclature. We thank Storrs Olson for sharing with us his summarization on the taxonomy and naming of indigenous Hawaiian birds. -

Non-Native Trees Provide Habitat for Native Hawaiian Forest Birds

NON-NATIVE TREES PROVIDE HABITAT FOR NATIVE HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS By Peter J. Motyka A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science In Biology Northern Arizona University December 2016 Approved: Jeffrey T. Foster, Ph.D., Co-chair Tad C. Theimer, Ph. D., Co-chair Carol L. Chambers, Ph. D. ABSTRACT NON-NATIVE TREES PROVIDE HABITAT FOR NATIVE HAWAIIAN FOREST BIRDS PETER J. MOTYKA On the Hawaiian island of Maui, native forest birds occupy an area dominated by non- native plants that offers refuge from climate-limited diseases that threaten the birds’ persistence. This study documented the status of the bird populations and their ecology in this novel habitat. Using point-transect distance sampling, I surveyed for birds over five periods in 2013-2014 at 123 stations across the 20 km² Kula Forest Reserve (KFR). I documented abundance and densities for four native bird species: Maui ‘alauahio (Paroreomyza montana), ʻiʻiwi (Drepanis coccinea), ʻapapane (Himatione sanguinea), and Hawaiʻi ʻamakihi, (Chlorodrepanis virens), and three introduced bird species: Japanese white-eye (Zosterops japonicas), red-billed leiothrix (Leiothrix lutea), and house finch (Haemorhous mexicanus). I found that 1) native forest birds were as abundant as non-natives, 2) densities of native forest birds in the KFR were similar to those found in native forests, 3) native forest birds showed varying dependence on the structure of the habitats, with ʻiʻiwi and ‘alauahio densities 20 and 30 times greater in forest than in scrub, 4) Maui ‘alauahio foraged most often in non-native cape wattle, eucalyptus, and tropical ash, and nested most often in non-native Monterey cypress, Monterey pine, and eucalyptus. -

The Relationships of the Hawaiian Honeycreepers (Drepaninini) As Indicated by Dna-Dna Hybridization

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE HAWAIIAN HONEYCREEPERS (DREPANININI) AS INDICATED BY DNA-DNA HYBRIDIZATION CH^RrES G. SIBLEY AND Jo• E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--Twenty-twospecies of Hawaiian honeycreepers(Fringillidae: Carduelinae: Drepaninini) are known. Their relationshipsto other groups of passefineswere examined by comparing the single-copyDNA sequencesof the Apapane (Himationesanguinea) with those of 5 speciesof carduelinefinches, 1 speciesof Fringilla, 15 speciesof New World nine- primaried oscines(Cardinalini, Emberizini, Thraupini, Parulini, Icterini), and members of 6 other families of oscines(Turdidae, Monarchidae, Dicaeidae, Sylviidae, Vireonidae, Cor- vidae). The DNA-DNA hybridization data support other evidence indicating that the Hawaiian honeycreepersshared a more recent common ancestorwith the cardue!ine finches than with any of the other groupsstudied and indicate that this divergenceoccurred in the mid-Miocene, 15-20 million yr ago. The colonizationof the Hawaiian Islandsby the ancestralspecies that radiated to produce the Hawaiian honeycreeperscould have occurredat any time between 20 and 5 million yr ago. Becausethe honeycreeperscaptured so many ecologicalniches, however, it seemslikely that their ancestor was the first passefine to become established in the islands and that it arrived there at the time of, or soon after, its separationfrom the carduelinelineage. If so, this colonist arrived before the present islands from Hawaii to French Frigate Shoal were formed by the volcanic"hot-spot" now under the island of Hawaii. Therefore,the ancestral drepaninine may have colonizedone or more of the older Hawaiian Islandsand/or Emperor Seamounts,which also were formed over the "hot-spot" and which reachedtheir present positions as the result of tectonic crustal movement. -

25 Using Community Group Monitoring Data to Measure The

25 Using Community Group Monitoring Data To Measure The Effectiveness Of Restoration Actions For Australia's Woodland Birds Michelle Gibson1, Jessica Walsh1,2, Nicki Taws5, Martine Maron1 1Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, Brisbane, 4072, Queensland, Australia, 2School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Melbourne, 3800, Victoria, Australia, 3Greening Australia, Aranda, Canberra, 2614 Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 4BirdLife Australia, Carlton, Melbourne, 3053, Victoria, Australia, 5Greening Australia, PO Box 538 Jamison Centre, Macquarie, Australian Capital Territory 2614, Australia Before conservation actions are implemented, they should be evaluated for their effectiveness to ensure the best possible outcomes. However, many conservation actions are not implemented under an experimental framework, making it difficult to measure their effectiveness. Ecological monitoring datasets provide useful opportunities for measuring the effect of conservation actions and a baseline upon which adaptive management can be built. We measure the effect of conservation actions on Australian woodland ecosystems using two community group-led bird monitoring datasets. Australia’s temperate woodlands have been largely cleared for agricultural production and their bird communities are in decline. To reverse these declines, a suite of conservation actions has been implemented by government and non- government agencies, and private landholders. We analysed the response of total woodland bird abundance, species richness, and community condition, to two widely-used actions — grazing exclusion and replanting. We recorded 139 species from 134 sites and 1,389 surveys over a 20-year period. Grazing exclusion and replanting combined had strong positive effects on all three bird community metrics over time relative to control sites, where no actions had occurred. -

Adaptive Radiation

ADAPTIVE RADIATION Rosemary G. Gillespie,* Francis G. Howarth,† and George K. Roderick* *University of California, Berkeley and †Bishop Museum I. History of the Concept ecological release Expansion of habitat, or ecological II. Nonadaptive Radiations environment, often resulting from release of species III. Factors Underlying Adaptive Radiation from competition. IV. Are Certain Taxa More Likely to Undergo Adap- founder effect Random genetic sampling in which tive Radiation Than Others? only a few ‘‘founders’’ derived from a large popula- V. How Does Adaptive Radiation Get Started? tion initiate a new population. Since these founders VI. The Processes of Adaptive Radiation: Case carry only a small fraction of the parental popula- Studies tion’s genetic variability, radically different gene VII. The Future frequencies can become established in the new colony. key innovation A trait that increases the efficiency with GLOSSARY which a resource is used and can thus allow entry into a new ecological zone. adaptive shift A change in the nature of a trait (mor- natural selection The differential survival and/or re- phology, ecology, or behavior) that enhances sur- production of classes of entities that differ in one or vival and/or reproduction in an ecological environ- more hereditary characteristics. ment different from that originally occupied. sexual selection Selection that acts directly on mating allopatric speciation The process of genetic divergence success through direct competition between mem- between geographically separated populations lead- bers of one sex for mates or through choices made ing to distinct species. between the two sexes or through a combination of character displacement Divergence in a morphological both modes.