LADP II Prodoc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Print Version (PDF)

K2 Team Tank: Objective Camel Armor in Support of Special Operations by Robert W. Jones, Jr. A������� Army Special North).2 A�er taking three days to arrive, Operations Forces (ARSOF) are not usu- however, the armor force was not able ally associated with armored units, they to effectively leave the airfield perimeter have been known to work together when to provide an immediate impact on the the situation has warranted heavy sup- combat situation in northern Iraq. In fact, port. During World War II, the legendary three days a�er TF 1-63’s arrival, the major Colonel William O. Darby formed the Iraqi elements in the north surrendered, Captain Celeen’s provisional “Cannon Company” of four and Kurdish Peshmerga and Task Force M1A1 Abrams tank M-3 half-tracks mounted with 75mm guns Viking (10th Special Forces Group) seized accidentally drove to give additional firepower to the Rang- Kirkuk and Mosul. TF 1-63 only entered into a large hole as it ers during the Italian campaign.1 However, operations in the north as an occupying traveled at high speed not until Operation IRAQI FREEDOM force in the cities controlled by TF Viking.3 with no illumination (OIF) did ARSOF again work with armor With such a tenuous association in the during the assault on Objective Camel. forces to any appreciable degree, and north, it again fell to the Rangers to prove Because the tank even then, the association was weak. the worth of armor in special operations. entered the deep well Early in operations, armored Task Force In a situation reminiscent of that faced from the wrong end, (TF) 1-63 was airli�ed into Bashur Airfield by Darby and the Rangers in World War it flipped over and in support of Combined Joint Special II, the 75th Ranger Regiment found itself landed with its turret Operations Task Force-North (CJSOTF- in need of armor support in Iraq. -

National Development Plan

National Development Plan 2013-2017 Republic of Iraq Ministry of Planning National Development Plan 2013 – 2017 Baghdad January 2013 Preface by the Minister of Planning A clear and defined path for development can only be mapped out through the creation of medium- and long- term plans and strategies built on sound methodology and an accurate reading of the economic, social, urban, and environmental reality. All the possibilities, problems, and challenges of distributing the available material and human resources across competing uses must be taken into consideration to maximize results for the national economy and the broader society. Three years of implementation of the 2010-2014 National Development Plan have resulted in important successes in certain areas and setbacks in others. It’s not fair to say that responsibility for the failures lies with the policies and programs adopted in the previous plan. The security and political dimensions of the surrounding environment, the executive capabilities of the ministries and governorates, the problems that continue to hinder the establishment and implementation of projects, weak commitment to the plan, and the weak link between annual investment budgets and plan priorities, along with the plan targets and the means of reaching these targets are all factors that contributed to these setbacks in certain areas and require that this plan be met with a high degree of compliance. The official decision announcing the 2010-2014 National Development Plan document included following up on plan goals in 2012 to monitor achievements and diagnose failures. In addition, it included keeping up with world economic developments and the effects and repercussions of the financial crisis on all economic conditions, in particular oil prices and developments in oil production and exports in Iraq, expectations of increasing it over the medium term through oil licensing rounds, and the effects of this on the great increase anticipated in the resources available for development and relative improvement in security. -

Weekly Iraq .Xplored Report 11 March 2017

Weekly Iraq .Xplored report 11 March 2017 Prepared by Risk Analysis Team, Iraq garda.com/ips Confidential and proprietary © GardaWorld Weekly Iraq .Xplored Report 11 March 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................... 2 ACTIVITY MAP .................................................................................................................................................... 3 OUTLOOK ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Short term outlook ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Medium to long term outlook ............................................................................................................................ 4 SIGNIFICANT EVENTS ...................................................................................................................................... 5 HRW claims PMU forces forced families accused of IS association from their homes ............................. 5 ‘No evidence’ of IS using chemical weapons in Mosul attack....................................................................... 5 THREAT MAP ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Burning Bridge: the Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean

Burning Bridge The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean Foreword by LTG (Ret.) H.R. McMaster David Adesnik & Behnam Ben Taleblu June 2019 FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES FOUNDATION Center on Military CMPP and Political Power Burning Bridge The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean Foreword by LTG (Ret.) H.R. McMaster David Adesnik Behnam Ben Taleblu June 2019 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Burning Bridge: The Iranian Land Corridor to the Mediterranean Table of Contents FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 7 IRANIAN STRATEGY AND THE LAND BRIDGE ........................................................................... 9 The Land Bridge Evolves .....................................................................................................................................11 The Southern Route Emerges .............................................................................................................................12 IRAN’S “RESISTANCE HIGHWAY” ................................................................................................... 13 DEBATING THE LAND BRIDGE ..................................................................................................... -

The Islamic State After Mosul

v Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Objective • Relevant • Rigorous | October 2016 • Volume 9, Issue 10 FEATURE ARTICLE A VIEW FROM THE CT FOXHOLE The Islamic State LTG(R) Charles after Mosul Cleveland Former Commanding General, How the Islamic State could regenerate in Diyala U.S. Army Special Operations Michael Knights and Alex Mello Command FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala: How the Islamic State Could Exploit Editor in Chief Iraq’s Sectarian Tinderbox Paul Cruickshank Michael Knights and Alex Mello Managing Editor Kristina Hummel INTERVIEW 8 A View from the CT Foxhole: LTG(R) Charles T. Cleveland, former EDITORIAL BOARD Commanding General, U.S. Army Special Operations Command Kristina Hummel Colonel Suzanne Nielsen, Ph.D. Department Head FEATURE COMMENTARY Dept. of Social Sciences (West Point) Lieutenant Colonel Bryan Price, Ph.D. 12 Lessons from the Fifteen-Year Counterterrorism Campaign Andrew Liepman and Philip Mudd Director, CTC Brian Dodwell ANALYSIS Deputy Director, CTC 16 Unseating the Caliphate: Contrasting the Challenges of Liberating Fallujah and Mosul CONTACT Zana Gulmohamad Combating Terrorism Center 28 Revising the History of al-Qa`ida’s Original Meeting with Abu Musab al- U.S. Military Academy Zarqawi 607 Cullum Road, Lincoln Hall Brian Fishman West Point, NY 10996 Phone: (845) 938-8495 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ctc.usma.edu/sentinel/ With a constellation of Iraqi forces making slow but sustained progress toward the outskirts of Mosul, Zana Gulmohamad compares the chal- lenges in liberating and securing the city with those faced by Iraqi forces SUBSMISSIONS in Fallujah earlier this year, based on interviews with key Iraqi players. -

Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala: How the Islamic State Could Exploit Iraq’S Sectarian Tinderbox by Michael Knights and Alex Mello

OCTOBER 2016 CTC SENTINEL 1 Losing Mosul, Regenerating in Diyala: How the Islamic State Could Exploit Iraq’s Sectarian Tinderbox By Michael Knights and Alex Mello Diyala’s Role as a Base for the Insurgency The Islamic State may be driven out of Mosul in the Since 2003, Diyala province1 has served as a fallback location for coming months, which would effectively destroy the the takfiria predecessors of the Islamic State—the Islamic State of group’s pretensions of administering a caliphate in Iraq (ISI) and before that al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI). As Diyala-based Iraq. But the Islamic State has vowed to fight on, and if coalition interrogator Richard Buchanan noted in 2014, “The re- the past is prologue, the group may eye an opportunity covery and refit area for the Sunni insurgents was always Diyala to regenerate in Diyala province, Iraq’s sectarian province. The insurgents who were married moved their families there, and their wounded would be often moved there as well.”2 tinderbox. By escalating terrorist attacks against Shi`a When the U.S. surge cleared Anbar in 2007, ISI fell back into Diyala targets there, the group could create a spiral of sectarian and very nearly took over the entire province. In the second quarter violence that it could exploit to make a comeback. The of 2007, an average of 418 attacks hit Diyala each month, mostly strategy almost worked a decade ago. After the U.S. against Shi`a targets, and the government lost its ability to expend surge cleared Islamic State of Iraq fighters from Anbar more than two percent of its budget or to distribute salaries or food province, the group made significant gains in Diyala by rations.3 In Baqubah, the provincial capital, ISI controlled the city carrying out a terrorist campaign against Shi`a targets center, and the U.S. -

Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways

1 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways In the Name of the Almighty 2 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways Information for the reader The present report offers an overview of rail transport in a number of countries in the Middle East (RAME members). It does not claim to be exhaustive. It is a compilation of information on Middle East Railways, networks and projects that was collected from various public sources and the related countries as well. The pursued objective was to describe the present situation in each country in a neutral way, without formulating any opinion or assessing the described rail transport systems. This document is the first version. Readers are invited to inform UIC M.E. Regional Office of any new development or changes in the information related to their network. We intend to update the report in order to make it reflect the rapid development that rail transport is experiencing in the Region. UIC M.E. Regional Office expresses thanks to all members who contributed to this report by providing information and data, and by lending us their support. May 2017 UIC Middle East Regional Office 3 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways Contents Page Information for the Reader …………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Afghanistan (ARA) ………………………………………………………………… 7 Iran (RAI) …………………………………………………………………………... 15 Iraq (IRR) …………………………………………………………………………... 22 Jordan (ARC, JHR) ………………………………………………………………… 30 Oman Rail ………………………………………………………………………….. 40 Qatar (QRC) ………………………………………………………………………... 47 Saudi Arabia (SRO) ………………………………………………………………... 55 Syria (CFS, SHR) …………………………………………………………………... 62 Turkey (TCDD) …………………………………………………………………….. 70 United Arab Emirates (FTA) ……………………………………………………….. 77 4 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways Introduction Transport today is of great importance for countries for their economic and social development. -

Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways May 2017

1 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways May 2017 In the Name of the Almighty 2 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways May 2017 Information for the reader The present report offers an overview of rail transport in a number of countries in the Middle East (RAME members). It does not claim to be exhaustive. It is a compilation of information on Middle East Railways, networks and projects that was collected from various public sources and the related countries as well. The pursued objective was to describe the present situation in each country in a neutral way, without formulating any opinion or assessing the described rail transport systems. This document is the first version. Readers are invited to inform UIC M.E. Regional Office of any new development or changes in the information related to their network. We intend to update the report in order to make it reflect the rapid development that rail transport is experiencing in the Region. UIC M.E. Regional Office expresses thanks to all members who contributed to this report by providing information and data, and by lending us their support. May 2017 UIC Middle East Regional Office 3 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways May 2017 CONTENTS Page Information for the Reader …………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………… 5 Afghanistan (ARA) ………………………………………………………………… 7 Iran (RAI) …………………………………………………………………………... 18 Iraq (IRR) …………………………………………………………………………... 27 Jordan (ARC, JHR) ………………………………………………………………… 37 Oman Rail ………………………………………………………………………….. 49 Qatar (QRC) ………………………………………………………………………... 57 Saudi Arabia (SRO) ………………………………………………………………... 67 Syria (CFS, SHR) …………………………………………………………………... 76 Turkey (TCDD) …………………………………………………………………….. 87 United Arab Emirates (FTA) ……………………………………………………….. 96 4 Current Outlook to the Middle East Railways May 2017 Introduction Transport today is of great importance for countries for their economic and social development. -

“International Transport Corridors in the OIC Member Countries”

A STUDY OF INTERNATIONAL TRANSPORT CORRIDORS IN OIC MEMBER COUNTRIES Prepared by September 2011 This publication was commissioned and funded by the Islamic Development Bank. PGlobal Global Advisory and Training Services This report has been prepared by “PGlobal Global Advisory and Training Services” upon the request of Islamic Development Bank (IDB) in 2011. Please see the “Disclaimer” section for further explanation. Preface Pre face The Study on Transport Corridors in OIC Member Countries is an assessment of the role and importance of transport corridors (TC) in contributing to economic growth and cooperation, trade and regional integration with a view to identify a policy framework among the 57 OIC member countries. It has conducted in order to present and to discuss prioritization of transport corridors passing through in OIC Member Countries in an international workshop in Izmir, attended by delegates from 21 OIC member countries and 11 international institutions. This exercise aims to identify priority TC and challenges together with policy formulation. In a more globalized and integrated world, TCs are commanding attention and gaining importance, particularly in developing economies and emerging markets, because of their role in economic development and trade facilitation. The report begin with examining potential trade movement among the countries by identifying the comparative advantage of each country adjacent to the relevant TCs, as well as the existing trade flow patterns and utilization level of those corridors. The report, therefore, aims to heavily underscore the need for efficient international TCs among the OIC member countries, as well as propose a set of priority TCs that deserve attention and inclusion in the political and development agenda of member countries and international organizations. -

TRAVEL ALERTS BEFORE YOU GO: Iraq IRAQ WEATHER CURRENCY

6/13/2014 iJET : Trip Brief Iraq (Prepared on Jun 13, 2014 3:48:33 AM GMT) TRAVEL ALERTS KEY: CRITICAL WARNING INFORMATIONAL 06/12/2014 - UPDATE 4: ISIS seizes Dhuluiya, Iraq June 12; Kurds take control of Kirkuk. More militant attacks likely. Avoid Highways 1 and 2 north of Baghdad. 06/13/2014 - UPDATE 5: Kurds confront ISIS, IA launches airstrikes June 12. More militant attacks likely. Avoid Highways 1 and 2 north of Baghdad. 06/04/2014 - UPDATE 1: Flooding near Fallujah, Abu Ghraib, and Baghdad, Iraq recedes after dam reopened May 6. Further flooding possible. Review flooding contingency plans. 06/11/2014 - Armed opposition groups expand their ability to mount major attacks in central Iraq and some areas south of Baghdad. Limit unnecessary movement. 06/04/2014 - Hundreds of thousands of Shia' to converge on Karbala, Iraq, June 14 for birthday of 12th Imam. Violence possible; avoid Karbala through at least June 17. 06/05/2014 - Officials watchful for polio activity in Syria and surrounding countries. Ensure up-to-date polio vaccination status before travel. BEFORE YOU GO: Iraq See Detailed Report below for full information. O verview: Iraq Security Security Overview of Iraq Civil Unrest: Civil unrest in Iraq. Crime: Major crime issues in Iraq. Kidnapping/Hostage Situation: The kidnapping threat in Iraq. Property Security: Hotel security in Iraq. Security: Emergency numbers and embassy contacts in Iraq. Security Services: Security services in Iraq. Terrorism: The terrorist threat in Iraq. Health Health Planning: Health considerations when traveling in Iraq. Immunizations: Recommended immunizations for travel to Iraq. Medical Facilities/Services: Medical facilities in Iraq. -

Master Plan Study for Port Sector in the Republic of Iraq Final Report

The Republic of Iraq General Company for Ports of Iraq (GCPI) MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR PORT SECTOR IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT DECEMBER 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency Ides Inc. Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. (NK) EI Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. (OCG) JR 15-208 MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR PORT SECTOR IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ MAIN REPORT December 2015 The Republic of Iraq General Company for Ports of Iraq (GCPI) MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR PORT SECTOR IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT DECEMBER 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency Ides Inc. Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. (NK) Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. (OCG) Exchange Rates Date: May 2014 1US$ = 1,163 Iraqi Dinar 1US$ = 101.72 Japanese Yen Master Plan Study for Port Sector in the Republic of Iraq Final Report Abbreviations AFGP Al Faw Grand Port AIS Automatic Identification System APL American President Line Limited BOT Build Operate Transfer CI Containerization International C.I.I.T.I. Italian Consortium for Iraqi Transport Infrastructure CIPP Complexo Industrial e Portuário do Pecém CMA-CGM Compagnie Maritime D'affrètement - Compagnie Générale Maritime CY Container Yard dB Decibel D/D Detailed Design DWT Dead Weight Tonnage EBA Endemic Bird Area EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMAP A Empresa Maranhense de Administração Portuária EMSA European Maritime Safety Agency ERP Enterprise Resource Planning E/S Engineering Service ESCAP Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific EU Europe Union FAL Convention on Facilitation -

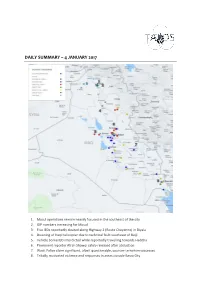

Daily Summary – 4 January 2017

DAILY SUMMARY – 4 JANUARY 2017 1. Mosul operations remain heavily focused in the southeast of the city 2. IDP numbers increasing for Mosul 3. Five IEDs reportedly cleared along Highway 2 (Route Cheyenne) in Diyala 4. Downing of Iraqi helicopter due to technical fault southeast of Baiji 5. Vehicle borne IED interdicted while reportedly travelling towards Haditha 6. Prominent reporter Afrah Shawqi safely released after abduction 7. Wasit Police claim significant, albeit questionable, counter-terrorism successes 8. Tribally motivated violence and responses in areas outside Basra City Iraq-wide: On 4 January US officials announced the number of US and Coalition advisors in Iraq has doubled over the last two weeks to approximately 450 personnel as part of the 4,935 US troops currently in the country. The announcement highlights increasing efforts to more closely embed Coalition personnel with command elements directing operations on the ground, thus increasing Iraqi military capabilities. Additional discussion of implications for this announcement will be reported in the Control of Terrain report issued on 5 January. On 4 January Iranian officials denied claims that Tehran and the KRG have agreed to building two pipelines for exporting KRG oil through Iran. Iranian Oil Ministry officials stated that any agreement would need to be negotiated with Baghdad. A visit by Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh to Baghdad is slated for next week, with discussions to include export of Kurdish oil through Iran amongst other issues. Any such exportation agreements potentially reached are expected to involve export of Kirkuk oil through Sulaymaniyah and onward though Iran. This would almost assuredly raise the ire of KDP officials and lead to questions of potential PUK-Baghdad-Tehran alliances which could further weaken efforts for Kurdish unity in the north.