Differential Coding in Property Words: a Typological Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DAS PHONETISCHE INSTITUT DER UNIVERSITÄT HAMBURG (1910–2006) Magnús Pétursson Institut Für Phonetik, Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft Und Indogermanistik, Hamburg

Simpozij OBDOBJA 35 DAS PHONETISCHE INSTITUT DER UNIVERSITÄT HAMBURG (1910–2006) Magnús Pétursson Institut für Phonetik, allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft und Indogermanistik, Hamburg UDK 81'34:929Topori{i~ J. V prispevku je kratko pojasnjena povezanost profesorja Jo`eta Topori{i~a s Foneti~nim in{titutom Univerze v Hamburgu. Profesor Topori{i~ je namre~ kot {tipendist Humboldtove ustanove izkoristil pomemben del svojega ~asa za znanstveno dejavnost na Univerzi v Ham- burgu. Hamburg, eksperimentalna fonetika, tonemi, intonacija, vizualizacija akusti~nih prvin The paper briefly presents the connection between Professor Jo`e Topori{i~ and the Institute of Phonetics at the University of Hamburg. As a scholarship holder of the Humboldt Foundation, Professor Topori{i~ was most of that time engaged in scholarly activities at the University of Hamburg. Hamburg, experimental phonetics, tonemes, intonation, visualisation of acoustic elements Das Phonetische Institut der Universität Hamburg wurde 1910 als »Phonetisches Laboratorium«, eine Abteilung im Afrikanischen Seminar des Kolonialinstituts (1908–1919), dem Vorläuferinstitut der Universität Hamburg, gegründet. Die vordringliche Aufgabe des Afrikanischen Seminars war die Erforschung der afrikanischen und ostasiatischen Kolonialsprachen in den damals deutschen Kolo- nien. Dies sollte mithilfe der modernsten Forschungsmethoden, den experimentell- phonetischen Methoden, durchgeführt werden. Ein junger Wissenschaftler, Giulio Panconcelli-Calzia (1878–1966), wurde mit der Leitung des Phonetischen Labo- ratoriums beauftragt. Unter seiner Führung (von 1910 bis 1949) erlangte das Phonetische Laboratorium, das mit der Gründung der Universität Hamburg im Jahr 1919 eine selbständige Forschungseinrichtung wurde, großes Ansehen und wurde weltbekannt. Neben der intensiven Erforschung allgemein phonetischer Fragestellungen wurden bald erste Versuche zur Behandlung sprech- und hörgeschädigter Menschen unternommen. Im Ersten Weltkrieg wurden sprachgeschädigte und traumatisierte Soldaten behandelt. -

Curriculum Vitae –

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Dr. Jan Marcus Research Associate Assistant Professor DIW Berlin University of Hamburg Mohrenstraße 58 Von-Melle-Park 5 10117 Berlin 20146 Hamburg [email protected] [email protected] German, married, born 1983 Employment Oct 2015 Assistant Professor for Econometrics - today University of Hamburg Oct 2015 Research Associate - today DIW Berlin, Department Education and Family, part-time Apr 2013 Research Associate - Sep 2015 DIW Berlin, Department Education and Family, full-time Dec 2010 Research Assistant - Mar 2013 DIW Berlin, Department SOEP (Socio-Economic Panel Study), part-time Education Sep 2009 PhD in Economics, TU Berlin - Jul 2013 Thesis “Four Essays on Causal Inference in Health Economics” (summa cum laude) 2007 - 2009 Master of Arts, International Economics, University of Konstanz Grade: very good (1.4) 2004 - 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Political and Administrative Science, University of Konstanz Grade: excellent (1.3). Rank: 1st (out of 60) Awards & scholarships 2018 German Economics Prize (Deutscher Wirtschaftspreis) Joachim Herz Stiftung, category: junior researcher, 25 000 Euro 2016 Award for the best DIW-Wochenbericht in 2015 2015 Dissertation prize German Academic Scholarship Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes), 2nd prize 2010 - 2013 PhD scholarship German Academic Scholarship Foundation 2012 Best Paper Prize for Young Economists Warsaw International Economic Meeting 2010 ALLBUS Young Scholar Award Best young scholar paper using ALLBUS data, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences 2009 - 2010 PhD scholarship Graduate Center of DIW Berlin 2005 - 2009 Study scholarship Friedrich Ebert Foundation 2008 Award for best graduation in Political and Administrative Science University of Konstanz, Alumni Association (VEUK) Publications Key publications 2019 The effect of increasing education efficiency on university enrollment: Evidence from administrative data and an unusual schooling reform in Germany. -

Academic Relations in Medical Sciences Between Iran and Germany

ISFAHAN UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES AND HEALTH SERVICES ACADEMIC RELATIONS IN MEDICAL SCIENCES BETWEEN IRAN AND GERMANY Industry and Academy Representatives of German medical equipment companies met Isfahan medical university authories in Isfahan in May 2017. DAAD Workshop Isfahan Medical University faculty members and students attended a workshop on DAAD educational and research programs and opportunies in Isfahan in May 2017. A Scientific Experience in Germany June 1- July 8, 2017 An Iranian scientific delegation visited Hamburg University. Training workshops, discussions over joint research projects, and visits to rehabilitation centers including Kurt Junter Schule were among the outcomes. Scientific Workshop in Isfahan July 2017 German scholars held a workshop on psychosomatic issues in Psychosomatic Research Center in Isfahan in July 12- 14 in Isfahan. Prof. Fleischer’s lecture August 28, 2017 Faculty members and students of immunology attended a lecture by Professor Fleischer in Isfahan Medical School. Hochschule Neu Ulm and Isfahan Medical University Collaboration September, 2017 Professor Uta Feser, the chancellor of HNU and Isfahan Medical University signed an MOU to collaborate in health management, IT, joint postgraduate programs and research projects. Scientific Psychosomatic Conference September 2017 The conference and visits following it were in line with the joint research project currently conducted by Hamburg psychology school and Isfahan psychosomatic research center. Dr. Daniel Petersheim’s lecture October 2017 Dr. Daniel Petersheim from Ludwigs-Maximilians-University (LMU) spent a one month clinical fellowship period in Isfahan Medical School during which parties exchanged scientific knowledge. Scientific Meeting in Isfahan To develop collateral cooperation, psychosomatic scholars from Germany and Iran held a meeting in November 2017. -

Robert Vincent Kelz

ROBERT VINCENT KELZ Professional Address Department of World Languages & Literature The University of Memphis 108 Jones Hall Memphis, TN 38152 [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Associate Professor of German, University of Memphis Associate Director of International Studies, University of Memphis EDUCATION 2006 - 2010 Ph.D., German Studies, Vanderbilt University Advisors: Dr. Meike Werner, Dr. Vera Kutzinksi, Dr. John McCarthy 2008 - 2009 Yearlong research at the Argentine National Library Mariano Moreno and the IWO Institute for Jewish Research in Buenos Aires, Argentina 2007 - 2008 Yearlong research at the Walter A. Berendsohn Research Center for German Exile Literature in Hamburg, Germany 2002 - 2006 M.A., German, Vanderbilt University 2003 - 2004 Graduate Exchange Program, Free University of Berlin 1994 - 1998 B.A., English and German, Tulane University 1996 - 1997 Undergraduate Exchange Program, University of Hamburg AWARDS, FELLOWSHIPS, AND GRANTS 2018 – 2021 Dunavant Professorship, University of Memphis 2016 - 2017 Professional Development Assignment, University of Memphis 2015 Alumni Association Distinguished Teaching Award, University of Memphis 2015 College of Arts and Sciences Early Career Research Award, University of Memphis 2011- 2013 Research Fellowship, Julio E. Payró Institute, University of Buenos Aires 2008 - 2009 Center for the Americas Dissertation Fellowship, Vanderbilt University 2007 - 2008 German Academic Exchange Service Research Stipend, Hamburg and Berlin, Germany 1998 - 1999 J. William Fulbright Scholarship, Berlin, Germany Robert Kelz CV—page 2/5 BOOKS Current Antifascist Exile and Intercultural Advocacy: Paul Zech’s Correspondence and Collaboration with the Chilean Newspaper, Deutsche Blätter (work in progress). 2020 Competing Germanies: The Free German Stage and the German Theater in Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1934-1964 (Ithica and London: Cornell University Press, 2020). -

College Codes (Outside the United States)

COLLEGE CODES (OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES) ACT CODE COLLEGE NAME COUNTRY 7143 ARGENTINA UNIV OF MANAGEMENT ARGENTINA 7139 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF ENTRE RIOS ARGENTINA 6694 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF TUCUMAN ARGENTINA 7205 TECHNICAL INST OF BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA 6673 UNIVERSIDAD DE BELGRANO ARGENTINA 6000 BALLARAT COLLEGE OF ADVANCED EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 7271 BOND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7122 CENTRAL QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7334 CHARLES STURT UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6610 CURTIN UNIVERSITY EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6600 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 7038 DEAKIN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6863 EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7090 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6901 LA TROBE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6001 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 6497 MELBOURNE COLLEGE OF ADV EDUCATION AUSTRALIA 6832 MONASH UNIVERSITY AUSTRALIA 7281 PERTH INST OF BUSINESS & TECH AUSTRALIA 6002 QUEENSLAND INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 6341 ROYAL MELBOURNE INST TECH EXCHANGE PROG AUSTRALIA 6537 ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AUSTRALIA 6671 SWINBURNE INSTITUTE OF TECH AUSTRALIA 7296 THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA 7317 UNIV OF MELBOURNE EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7287 UNIV OF NEW SO WALES EXCHG PROG AUSTRALIA 6737 UNIV OF QUEENSLAND EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 6756 UNIV OF SYDNEY EXCHANGE PROGRAM AUSTRALIA 7289 UNIV OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA EXCHG PRO AUSTRALIA 7332 UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE AUSTRALIA 7142 UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA 7027 UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUSTRALIA 7276 UNIVERSITY OF NEWCASTLE AUSTRALIA 6331 UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND AUSTRALIA 7265 UNIVERSITY -

Tabellarischer Lebenslauf

Curriculum Vitae Name Professor Jalid Sehouli, M.D., Dr. h. c. Birthday/ -place 1968, April 19th / Berlin Nationality German, Moroccan Current Positions Director of the Clinic of Gynecology, Charité Campus Virchow Clinic, Berlin Director of the Clinic of Gynecology, Charité Campus Benjamin Franklin, Berlin Head of the European Competence Center for Ovarian Cancer (EKZE), Charité Campus Virchow Clinic, Berlin, Head of the Interdisciplinary Center of Gynecological Cancer of the Charité Co-Director of the Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center Executive Faculty Member: Global Health Charité Academic Career 06/2019 Doctor honoris causa/University Cluj/Romania 10/2014 Acceptance of Professorship for Gynecology for life at Charité University Medicine Berlin 06/2013 Invitation for full professorship of gynecology to University of Hamburg-Eppendorf/Germany 10/2007 Professorship for Gynecology at Charité University Medicine Berlin 01/2005 Habilitation (postdoctoral lecturer qualification) at the Humboldt-University with the theme: “Multimodal Management in Malignant Ovarian Tumors“ 01/2005 Certification for student teaching: Gynecology and Obstetrics 09/1998 Doctoral thesis: Postoperative use unconventional cancer therapies in gynaecologic oncology 07/2005- MBA, Diploma in Business Management 06/2006 Health Economics, Business University of Ural Academic Education 04/1989 Study of human medicine at the Humboldt-University Berlin 03/1991 Preliminary medical examination 03/1992 1. State examination 04/1994 2. State examination 05/1995 3. State examination 2 Professional Education 04/1988-04/1989 Apprenticeship to nursery / University of Berlin, Charité, Campus Virchow-Klinikum 07/1995-01/1996 Medical doctor in practice 07/1995-09/1996 Hospital: Ernst-von-Bergmann-Klinikum Gynecology and Obstetrics Director: Prof. Dr. -

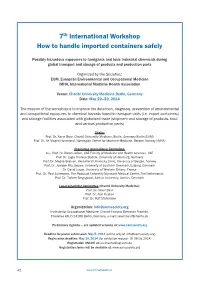

7Th International Workshop How to Handle Imported Containers Safely

7th International Workshop How to handle imported containers safely Possibly hazardous exposures to fumigants and toxic industrial chemicals during global transport and storage of products and production parts Organized by the Societies: EOM, European Environmental and Occupational Medicine IMHA, International Maritime Health Association Venue: Charité University Medicine Berlin, Germany Date: May 22–23, 2014 The mission of the workshop is to improve the detection, diagnosis, prevention of environmental and occupational exposures to chemical hazards found in transport units (i.e. import containers) and storage facilities associated with globalized trade (shipment and storage of products, food and various production parts) Chairs: Prof. Dr. Xaver Baur, Charité University Medicine. Berlin, Germany Berlin (EOM) Prof. Dr. Alf Magne Horneland, Norwegian Center for Maritime Medicine, Bergen, Norway (IMHA) Organizing International Committee: Ass. Prof. Dr. Balazs Adam, UAE Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, UAE Prof. Dr. Lygia Therese Budnik, University of Hamburg, Germany Prof. Dr. Magne Bratveit, Haukeland University Clinic, University of Bergen, Norway Prof. Dr. Joergen Riis Jepsen, University of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, Denmark Dr. David Lucas, University of Western Britany, France Prof. Dr. Paul Scheepers, The Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, The Netherlands Prof. Dr. Torben Siegsgaard, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Local organizing Committee (Charité University Medicine): Prof. Dr. Xaver Baur Prof. Dr. Axel Fischer -

A New Reference Data Set for Climate Simulations Over Sea

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-10552, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. The Baltic and North Seas Climatology - a new reference data set for climate simulations over sea Corinna Jensen (1), Annika Jahnke-Bornemann (2), and Birger Tinz (3) (1) Federal Maritime Hydrographic agency, Hamburg, Germany ([email protected]), (2) University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany, (3) Deutscher Wetterdienst, Hamburg, Germany The Baltic and North Seas Climatology (BNSC) is a new climatology calculated solely from marine in situ observations. It was created in cooperation between the University of Hamburg (UHH), the Federal Maritime and Hydrographic Agency (BSH) and the Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD). It was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure (BMVI) within the “Network of Experts” and publically released through the Integrated Data Center (ICDC, www.icdc.cen.uni-hamburg.de) in 2018. The climatology consists of an atmospheric and a hydrographic part in the region of the Baltic Sea, the North Sea and adjacent regions of the North Atlantic. As it includes homogenous fields both for the atmosphere and the ocean on a corresponding grid, it is especially a valuable tool to validate regionally coupled climate simulations over sea. The atmospheric part consists of time series of monthly mean gridded fields for 2m air temperature, 2m dew point and sea level pressure from 1950 to 2015 on a 1◦x1◦ grid. The hydrographic part includes the variables water temperature and salinity from 1873 to 2015 with a grid of 105 depth levels and a 0.25◦ horizontal resolution. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Since 2006 (Aug.) Lecturer in Sanskrit (Lektor für Sanskrit), Department of Classical Indology, South Asia Institute, University of Heidelberg. 2006 (Mai) – 2006 (Juli) Visiting Numata Professor at the Department for Culture and History of India and Tibet, Asia-Afrika-Institute, University of Hamburg, Germany. 2005 (September) - 2006 (April) University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA, Lecturer in South and South Asian Buddhism. 2001 (April) – 2005 (August) Academic Assistant (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter): Replacement of Assistant Professor (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter: Vertretung der wissenschaftlichen Assistenten-Stelle) in Indology and Buddhist Studies at the Institute for Indology and Central Asian Studies, University of Leipzig (full time: Sanskrit, Pāli, Sinhalese and Buddhist Studies). 1998 (May) to 2000 (December) Lecturer for Theravāda Buddhism and Pāli at the Theravāda Buddhist Centre (Buddhistische Gesellschaft Hamburg e.V.). 1997 (October - March 1998) – 1999 (October - March 2000) Sessional Lecturer (Lehrbeauftragter) for Pāli, Sanskrit and Theravāda Buddhism at the Department for Oriental Studies, University of Kiel. 1997 (April) to 2001 (March) Sessional Lecturer (Lehrbeauftragter) for Buddhism, Pāli and Sinhalese at the Institute for Indology and Central Asian Studies, University of Leipzig. 1996 (August) to 2001 (March) Academic Assistant (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter) in the project to catalogue the Asian manuscripts kept in Germany ("Katalogisierung der orientalischen Handschriften in Deutschland"), -

CURRICULUM VITAE Alexander Von Rospatt Spring 2020

CURRICULUM VITAE Alexander von Rospatt spring 2020 University Education • April 2001 Completion of the post-doctoral habilitation thesis, submitted at the University of Hamburg, entitled Te Periodic Renovations of the Trice-Blessed Svayambhūcaitya of Kathmandu. • 1988-1993 University of Hamburg: Ph.D with a thesis on Te Buddhist Doctrine of Momentariness (published in 1995). • 1985-1988 University of Hamburg: Master of Arts in Indology with Religious Studies and Tibetology as minor subjects. • 1982-85 School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London: Bachelor of Arts in Religious Studies with History Academic Appointments • Since August 2003 Appointment as Professor of Buddhist and South Asian Studies in the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. (2007-2011 Department Chair; since 2012 Director of the Group in Buddhist Studies) • February 2002 - July 2003 Visiting Professor for Buddhist Studies (standing in for Prof. Ernst Steinkellner) at the Institute for South Asian-, Tibetan and Buddhist Studies at the University of Vienna. • September 2001 - December 2001 Visiting Numata Professor in Buddhist Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. • April 2001 - July 2001 Visiting Numata Professor in Buddhist Studies at the University of Oxford, Balliol College. • April 1993 - March 2001 Assistant Professor (Hochschulassistent) at the Institute for Indology at Leipzig University, Germany. (March 1997 - February 2000: Tree year leave as German Research Council fellow for pursuing a research project in Kathmandu on the Svayambhunath stupa.) • February 1988 - September 1990 Appointment as researcher (wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter) at Hamburg University, cataloguing manuscripts microfilmed by the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project. 1 Grants, Awards and Honors • summer term 2019 Visiting Professorship at the Ludwig Maximilians University Munich – LMU • December 2017 Directeur d'études at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Études – Section des Sciences religieuses, PLS Research University Paris. -

Prof. Dr. Stefan Voss

SYSTEMS INFORMATION Prof. Dr. Stefan Voß SHORT INFORMATION PR ............................................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................................. areas, and skills to generate crea- • An exact algorithm for the tive solution approaches through reliability redundancy alloca- sound methodological knowledge. tion problem (with M Caserta). European Journal of Opera- tional Research 244 (2015) █ RESEARCH 110-116 The main focus of Prof. Voß´ inter- • Design and evaluation of road ests is located in the fields of In- pricing: State-of-the-art and formation Systems, Public Trans- methodological advances (with port, Telecommunications, Supply T Tsekeris). Netnomics 10 (2009) 5-52 Chain Management and Logistics as well as Intelligent Search. He • Dispatching of an electric █ COORDINATES has an international reputation as a monorail system: Applying me- OF. DR. STEFAN VO result of numerous publications in ta-heuristics to an online Chair and Director of the Institute these fields. pickup and delivery problem (with K Gutenschwager and C of Information Systems within the Current research projects are, Niklaus). Transportation Sci- Faculty of Business Administration among others, considering problem ence 38 (2004) 434-446 at the University of Hamburg (since formulations in the field of Infor- 2002) mation Systems in Supply Chain • A super-function based Japa- Management, Computational Lo- nese-Chinese machine trans- University of Hamburg gistics as well as Metaheuristics lation system for business us- Institut für Wirtschaftsinformatik and Intelligent Search Algorithms in ers (with X Zhao and F Ren). Von-Melle-Park 5 practical applications. In various Lecture Notes in Artificial Intel- D-20146 Hamburg, Germany areas the research of Prof. Voß ligence 3265 (2004) 271-281 +49-40-42838-3062 and the members of his institute • Container terminal operation Fax +49-40-42838-5535 may be rated as world-class. -

LINKS Simulations

Americas Cape Breton University St. Francis Xavier University Dalhousie University STEAM - APICS Dominican Republic Escuela Superior de Economia y Negocios Thompson Rivers University Fundação Getulio Vargas Universidad Francisco Marroquin IEEC Argentina Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Insper (Brazil) University of Alberta Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México University of Ontario Institute of Technology Manitoba International Marketing Competition University of Puerto Rico - Rio Piedras McMaster University University of Saskatchewan Mount Royal University University of Western Ontario Queen’s University University of Windsor Simon Fraser University Asia Pacific American University in Cairo Qatar University Aoyama Gakuin University S P Jain School of Global Management - Dubai Beijing International MBA S P Jain School of Global Management - Mumbai City University of Hong Kong S P Jain School of Global Management - Singapore EMPI University Business School (New Delhi) S P Jain School of Global Management - Sydney Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad Sungkyunkwan University (SKK GSB) Indian Institute of Management Bangalore Tokyo Institute of Technology Indian Institute of Management Indore University of Dubai Indian Institute of Management Lucknow University of Guam Indian School of Business University of Hong Kong International University of Japan University of Melbourne King Mongkut’s University of Technology University of New South Wales Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies University of South Australia Nankai