Continuity Within Chaos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solidarity and the Fall of Communism

Solidarity and the Fall of Communism Europejskie Centrum Solidarności Introduction Twenty years have passed since the 4th of June 1989, when the first non- fraudulent elections took place in the People’s Republic of Poland. Those ground-breaking elections were the starting point of the dismantling of the Communist system in Central and Eastern Europe and led to profound social and economic changes. The distinguished personalities of public life, scholars and most importantly, the heroes of those times, now congregate in Warszawa and Gdańsk to evaluate the last 20 years from historical, social and political perspectives. This auspicious assembly is also an opportunity to identify future challenges and find possible answers, using past experiences, of how to approach them. The events of 1989 were of great importance. Not only was it an unarmed fight but also the civic opposition had turned it into a peaceful revolution. Seldom in world history did the revolutions renounce violence bringing radical changes by peaceful means of accord and dialog. Peace and revolution, those usually contrasting words, in 1989 and through the following years described in the most suitable way, the unique changes of those times. The revolution commenced in August 1980. In Central Europe, separated from the rest of the world by the Iron Curtain, workers of the Gdansk Shipyard, paradoxically named after Lenin, supported by students, intellectuals, priests and journalists, utterly opposed the regime. They were followed by ten million Polish people who created a social movement with the symbolic name Solidarnosc. This solidarity led Poland to freedom. The same path was shortly followed by other nations. -

Protests Grow As U.S. Deepens Intervention in El Salvador U.S

Black party hits Salvador aid 3 TH£ Reagan's hypocrisy on Poland. 5 Rail workers vs. MX missile 14 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 46/NO. 7 FEBRUARY 26, 1982 75CENTS Protests grow as U.S. deepens intervention in El Salvador U.S. rulers' 'We're losing debate move the fight,' toward war says junta The Reagan administration is facing BY FRED MURPHY mounting troubles in El Salvador. De "We are losing the fight with the spite massive U.S. military aid, the jun guerrillas in the countryside," Salvado ta there is rapidly losing ground to the ran President Jose Napoleon Duarte ad rebel forces. And domestic opposition to mitted February 15. U.S. intervention in El Salvador is The next day, U.S. Defense Secretary growing apace. Caspar Weinberger said on NBC's "To This combined pressure is beginning day" show th~t there is "considerable to produce cracks and fissures within danger" Duarte's government will fall without stepped-up U.S. military and economic aid. EDITORIAL Weinberger insisted that Washington will not allow this to happen, and echoed Secretary of State Alexander Haig's re U.S. ruling circles on how best to pro cent declarations that the administra ceed in trying to thwart the victory of tion will do "whatever is necessary" to the Salvadoran revolution. prevent a victory by the Salvadoran Salvadoran troops in training at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina. Reagan adminis • Trade unionists demonstrating freedom fighters. tration has also prepared military operations aimed at Nicaragua and Cuba. -

2012Wp07cosmos

COSMOS WORKING PAPERS Grassroots Groups and Civil Society Actors in Pro-Democratic Transitions in Poland Grzegorz Piotrowski COSMOS WP 2012/7 COSMOS-Centre on social movement studies Mobilizing for Democracy – ERC Project Department of political and social sciences European University Institute This paper has been sponsored by the ERC Advanced Grant for the project Mobilizing for democracy. It can be do nloaded for personal research p!rposes only. Any additional reprod!ction for other p!rposes" whether in hard copy or electronically" re#!ires the consent of the a!thor$s%" editor$s%. If cited or q!oted" reference sho!ld be made to the f!ll name of the a!thor$s%" editor$s%" the title" the or&ing paper or other series" the year" and the p!blisher. E'R()EA* '*I+ER,IT- I*,TIT'TE" ./(RE*CE 0E)ARTME*T (F )(/ITICA/ A*0 ,(CIA/ ,CIE*CE, C(,M(, CE*TRE (F ,(CIA/ M(+EME*T ,T'0IE, 1M(2I/I3I*G .(R 0EM(CRAC-4 0EM(CRATI3ATI(* )R(CE,,E, A*0 T5E M(2I/I3ATI(* (F CI+I/ ,(CIET-6 )R(JECT E'R()EA* RE,EARC5 C('*CI/ $ERC% GRA*T Mobilizing for Democracy: Democratization Processes and the Mobilization of Civil Society The project addresses the role of civil society organizations (CSOs) in democratization processes, bridging social science approaches to social movements and democracy. The project starts by revisiting the “transitology” approach to democratization and the political process approach to social movements, before moving towards more innovative approaches in both areas. From the theoretical point of view, a main innovation will be in addressing both structural preconditions as well as actors’ strategies, looking at the intersection of structure and agency. -

One World in Schools Stories of Injustice Teaching Manual

T 544 ČSN 50 6210 Kčs 1,10 One WOrld in SchoolS StOrieS Of injuStice CommuniSt TotalitarianiSm in eurOpe teaching manual Krkonošské papírny, n. p., závod 01 Hostiné One World in Schools – StOrieS Of INJUSTICE STORIES OF INJUSTICE ONE WORLD IN SCHOOLS INTRODUCTION 5 A MANUAL ON METHODOLOGY ADVICE AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR WORKING WITH THE ACTIVITIES 6 STANDALONE ACTIVITY: MEMORY AND REMEMBERING 8 STANDALONE ACTIVITY: A LETTER TO THE UN SECRETARY-GENERAL 11 THE CASE OF DR. HORÁKOVÁ Summary of film 18 Activity: The trial as theatre 19 Questions and answers 26 INTERRUPTED SPRING: THE AUGUST HAMMER Summary of film 30 Activity: And what then? 31 Project: 1968 – Year of great changes 40 Questions and answers 44 SERIES: THE LOST SOUL OF A NATION Summary of film series 48 Questions and answers 49 THE LOST SOUL OF A NATION – LOSS OF DIGNITY Summary of film 54 Activity: An opinion of one’s own 55 Questions and answers 57 THE LOST SOUL OF A NATION – LOSS OF DECENCY Summary of film 58 Activity: Banished for life 59 Questions and answers 60 THE LOST SOUL OF A NATION – LOSS OF TRADITION Summary of film 62 Activity: Nationalized 63 Questions and answers 65 THE LOST SOUL OF A NATION – LOSS OF FAITH Summary of film 66 Activity: Monastic danger 67 Questions and answers 70 ADVICE AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR WORKING WITH DOCUMENTARY FILM 71 GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF INTERACTIVE LEARNING 73 METHODS OF INTERACTIVE LEARNING 74 [ 2 ] STORIES OF INJUSTICE ONE WORLD IN SCHOOLS THE HISTORY OF COMMUNIST TOTALITARIAN REGIMES IN EUROPE (1945–1989) 79 THE RISE OF STALINISM IN -

The 1988–1989 Transformation in Poland. the Authorities, the Opposition, the Church

DOI : 10.14746/pp.2020.25.2.9 Paweł STACHOWIAK Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9418-0935 The 1988–1989 transformation in Poland. The authorities, the opposition, the Church Abstract: The events that took place in Poland in 1988–1989 established a transformation model of which various elements tended to be replicated in other countries of the Soviet Bloc. Nevertheless, certain elements of the Polish transformation model were specific and unique, having sprouted from a specific historical context. The author of the paper proposes that the triad formed by “the authori- ties, the opposition and the Church” be considered a uniquely Polish aspect of the political and social transformation that took place after August 1980. The goal of this paper is to present this transforma- tion with respect to each of the above three actors. An analysis of their concepts and actions leads to the conclusion that Poland should be considered an exceptional model of transformation in Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish transformation model featured a key and unique element, the Catholic Church – an institution that played a considerable role in making the 1988–1989 transformation non- confrontational. Key words: Systemic change 1989, Model of transformation 1989, Poland 1989, Catholic Church 1989 tefan Kisielewski, aka “Kisiel,” a prominent Polish musician, columnist and excep- Stionally harsh critic of the communist state, used to say of the recurrent crises plagu- ing politics, economy and society during the communist era: “this is not a crisis, this is an outcome.” In this way, he captured a fundamental shortcoming of “real socialism;” as he perceived it, the advancing instability of the system heading towards collapse was a result of its intrinsic properties. -

Political Thought of the “Fighting Solidarity” Organisation

CHAPTER XIII FREEDOM, SOLIDARITY, INDEPENDENCE: POLITICAL THOUGHT OF THE “FIGHTING SOLIDARITY” ORGANISATION KRZYSZTOF BRZECHCZYN The goal of this article is to analyse the main lines of the political programme developed by the “Fighting Solidarity” organisation, centred on the three concepts given in the title, i.e. freedom, independence and solidarity. Since “Fighting Solidarity” is not prominently featured in books about Poland’s contemporary history, the first section of the article contains a brief description of the organisation’s history, while subsequent sections provide a description of the political thought developed by “Fighting Solidarity”. Section three contains an overview of the organisation’s attitude towards totalitarian communism; and section four, a synopsis of the idea of a “Solidary Republic”, which is in the political programme promoted by the organisation. The final section features a description of expectations of “Fighting Solidarity” members concerning the fall of communism and the consequential critical attitude of the negotiations conducted by representatives of “Solidarity” and the political opposition at the Round Table. Finally, the summary presents a concise evaluation of the organisation’s political thought. “FIGHTING SOLIDARITY” – A HISTORICAL OUTLINE “Fighting Solidarity” was established by Kornel Morawiecki in Wrocław in June 19821. The organisation was set up in response to growing disagreement between Władysław Frasyniuk and Kornel Morawiecki. The two activists were at variance as they promoted different methods of struggle with the communist system. In general, Frasyniuk claimed that social resistance should be a tool employed to force the authorities of the day to conclude another agreement with the society. Morawiecki contended that it should be a tool to oust the communists from power. -

ARTYKUŁ a Ground-Breaking Visit, Or a Visit of Ground- Breaking Times? Author: RADOSŁAW MORAWSKI 09.07.2020

ARTYKUŁ A ground-breaking visit, or a visit of ground- breaking times? Author: RADOSŁAW MORAWSKI 09.07.2020 On the late evening of July 9th 1989, Air Force One with president George H. W. Bush and his wife Barbara on board landed at the Okęcie airport in Warsaw. An official visit of the fourth American president on Polish lands began, lasting two days. Previously, Poland was visited by Richard Nixon (in 1972), Gerald Ford (in 1975) and Jimmy Carter (in 1977). Each of these visits gathered a lot of attention in the country over the Vistula river. Here were the leaders of one of the most powerful countries in the world, an oasis of freedom, for many years portrayed by the communist propaganda as the “rotten west”, visiting from behind the iron curtain. As Reagan’s vice president… Although George Bush visited Poland as the president of the USA, it was not his first visit in the country. Two years prior, in September 1987, he made a four-day trip to Poland as the deputy of Ronald Reagan. The visit in 1987 was quite peculiar for those times, since, apart from the scheduled, official meetings with the authorities of the Polish People’s Republic, Bush had a lot of private meetings with opposition activists. The visit in 1987 was quite peculiar for those times, since, apart from the scheduled, official meetings with the authorities of the Polish People’s Republic, Bush had a lot of private meetings with opposition activists (Lech Wałęsa, Bronisław Geremek, Zbigniew Bujak, Leszek Moczulski). Vice president Bush laid wreaths at the grave of priest Jerzy Popiełuszko and made a speech in the Polish television, where he mentioned his meeting with Wałęsa. -

The Polish Case

COMMUNITY of DEMOCRACIES THE POLISH CASE Permanent Secretariat of the Community of Democracies THE POLISH CASE Permanent Secretariat of the Community of Democracies Warsaw 2010 Published by the Permanent Secretariat of the Community of Democracies (PSCD) Al. Ujazdowskie 41, 00-540 Warsaw, POLAND www.community-democracies.org © PSCD, Warsaw 2010 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction be accompanied by an acknowledgment of the PSCD as the source. FOREWARD by Prof. Bronislaw Misztal Executive Director Permanent Secretariat of the Community of Democracies Retrospectively, the Polish case of democratic transformation, or the experience of a complex, co- temporal and multi-axial reconstruction of a social system is still a mystery and a miracle of history. It ran against political and military interests that cumulated on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Poland as the Western flank of the Communist territory was an important prong of this system. The transformative processes in Poland involved a number of changes in the areas of social and political life that were so solidly welded with the global political order of its era, and with the historical heritage of the region, that each of those changes alone seemed to be impossible, not to speak about any of them occurring concurrently. For those who lived through these changes (and there are still large segments of the Polish society that were coming of age in the late 1970s), who worked in Poland, posted there by news and media institutions, who observed the events working as diplomats, journalists, scholars or experts, the exhilaration of the 1980s sometimes overshadowed the complexity of this historical experience. -

POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate Scho

MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. By Siobhan K. Doucette, M.A. Washington, DC April 11, 2013 Copyright 2013 by Siobhan K. Doucette All Rights Reserved ii MIGHTIER THAN THE SWORD: POLISH INDEPENDENT PUBLISHING, 1976-1989 Siobhan K. Doucette, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrzej S. Kamiński, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes the rapid growth of Polish independent publishing between 1976 and 1989, examining the ways in which publications were produced as well as their content. Widespread, long-lasting independent publishing efforts were first produced by individuals connected to the democratic opposition; particularly those associated with KOR and ROPCiO. Independent publishing expanded dramatically during the Solidarity-era when most publications were linked to Solidarity, Rural Solidarity or NZS. By the mid-1980s, independent publishing obtained new levels of pluralism and diversity as publications were produced through a bevy of independent social milieus across every segment of society. Between 1976 and 1989, thousands of independent titles were produced in Poland. Rather than employing samizdat printing techniques, independent publishers relied on printing machines which allowed for independent publication print-runs in the thousands and even tens of thousands, placing Polish independent publishing on an incomparably greater scale than in any other country in the Communist bloc. By breaking through social atomization and linking up individuals and milieus across class, geographic and political divides, independent publications became the backbone of the opposition; distribution networks provided the organizational structure for the Polish underground. -

Generuj PDF Z Tej Stronie

Solidarność Walcząca https://sw.ipn.gov.pl/ws/history/5515,Fighting-Solidarity.html 2021-10-06, 17:17 Fighting Solidarity Fighting Solidarity (Polish: Solidarność Walcząca) was an underground anti-communist organisation operating in 1982-1992, founded in June 1982 in Wrocław, on the initiative of Kornel Morawiecki. After 13 December 1981 K. Morawiecki was the organiser of the underground printing and distribution structure of RKS "S" Lower Silesia, editor of "Z Dnia na Dzień", as of May 1982 under RKS "S" Dolny Ślask. In June 1982, in connection with a disagreement with W. Frasyniuk about how they should proceed further, he resigned from membership in RKS Lower Silesia and founded Fighting Solidarity. Unlike Frasyniuk, he was an advocate of deep conspiracy and the organisation of street demonstrations. The principles and rules of Fighting Solidarity were developed over several months. Initially, on 1 July 1982, the Fighting Solidarity Alliance was established. It was assumed that it would be a loose federation of groups and circles united under common ideals and one programme. This concept did not work in practice. On 11 November 1982 the Alliance was transformed into a single organisation called Fighting Solidarity. It was headed by a Council, consisting of a dozen or so councilors. The council elected K. Morawiecki president of Fighting Solidarity. The members of the council changed. It included: Zbigniew Bełz, Paweł Falicki, Michał Gabryel, Jerzy Gnieciak, Maria Koziebrodzka, Cezariusz Lesisz, Hanna Łukowska Karniej, Kornel Morawiecki, Andrzej Myc, Zbigniew Oziewicz, and Jan Pawłowicz. Later on it was joined by Jerzy Kocik and Władyslaw Sidorowicz. The autumn of 1984 brought decisions to create the Fighting Solidarity Executive Committee, a narrower decision-making structure composed of: Kornel Morawiecki, Andrzej Myc, Wojciech Myślecki and Andrzej Zarach, followed by Andrzej Kołodziej, Ewa Kubasiewicz, Hanna Łukowska Karniej and Jadwiga Chmielowska. -

NSZZ “Solidarity's”

Studies in Political and Historical Geography Vol. 8 (2019): 207–226 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2300-0562.08.11 Krystyna Krawiec-Złotkowska NSZZ “Solidarity’s” notions for the state’s role in social life Their social and political roots and status in 3rd Republic of Poland Abstract: The paper portrays the origins and ideological foundations of NSZZ “Solidarity” (Independent Self-governing Trade Union “Solidarity”) and their meaning in social life at the time of the communist regime in PRL (Polish People’s Republic). There are references to strikes (June ‘56 in Poznan, polish March ’68, June ’76, July ’80 in Lublin and Swidnica and August ’80) and, in 1980, the creation of Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee, which developed and published 21 demands aimed at the authorities. In the study, it is acknowledged that those demands are the ideological sources of Solidarity. The author of the text thinks that John Paul II sermons and encyclicals as well as Fr. Józef Tischner’s texts (published in the book Etyka solidarności oraz Homo sovieticus – Solidarity’s ethics and homo soviecticus) also had an influence on the formation of these ideas, which could bring back moral order, the rule of law, dignity and freedom for the society enslaved by Soviets. “Solidarity” also desired to improve the economic status of the country, particularly by ending the crisis. Those thoughts were, and are, beautiful; unfortunately, nowadays many of them exist only in the sphere of ideas or demands written in NSZZ Solidarity’s statute. Therefore, the article contains a sad conclusion, that in the 3rd Republic of Poland’s reality, “Solidarity’s” ideas are not attractive anymore. -

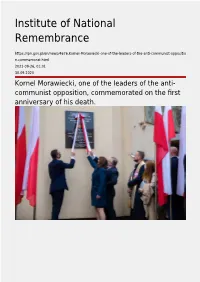

Generate PDF of This Page

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/4676,Kornel-Morawiecki-one-of-the-leaders-of-the-anti-communist-oppositio n-commemorat.html 2021-09-26, 01:01 30.09.2020 Kornel Morawiecki, one of the leaders of the anti- communist opposition, commemorated on the first anniversary of his death. A memorial plaque to this founder of the Fighting Solidarity has been unveiled in what today is the Museum of Cursed Soldiers and Political Prisoners in Warsaw, but back in the day was the Mokotów Prison, the place where the communists kept, tortured and murdered many opposition members, and where Kornel Morawiecki himself was detained in the 1980s. The event participants, among them the oppositionist’s son, Poland’s PM Mateusz Morawiecki, and the IPN’s President Jarosław Szarek, also saw an exhibit devoted to the deceased dissident. “This exhibition tells the story of brave people who did the right thing in difficult times. My father always looked for the good and the truth, and his public activity was in line with these values,” said Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki during the ceremony, “The history of Poland is the history of freedom. My father, asked what to do, would say, ‘Do whatever will make communism collapse.’ Thank you for remembering my father, for preserving those traditional Polish values which shaped us and which will determine the fate of Poland in the future. There is no value greater than Poland founded on freedom and solidarity,” he added. Kornel Morawiecki was one of these dissidents that any totalitarian regime fears most.