The Hartley's Jam Factory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 31-08-2015 and covers a total of 2879 related records from 24-08-2015 to 30-08-2015. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2015 年 8 月 31 日建立,包含從 2015 年 8 月 24 日到 2015 年 8 月 30 日到共 2879 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/註 冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. (D & A) Development Limited 2280098 28-08-2015 2. 100 Business Limited 100 分顧問有限公司 2278033 24-08-2015 3. 13 GLOBAL GROUP LIMITED 壹三環球集團有限公司 2279402 26-08-2015 4. 262 Island Trading Group Limited 2278529 24-08-2015 5. 3 Mentors Limited 2278378 24-08-2015 6. 3a Network Limited 三俠網絡有限公司 2278169 24-08-2015 7. 3D Systems Hong Kong Co., Limited 1016514 26-08-2015 8. 716 Studio Company Limited 716 工作室有限公司 2280037 28-08-2015 9. 80 INNOVATE TECHNOLOGY LIMITED 百翎創新科技有限公司 2278139 24-08-2015 10. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

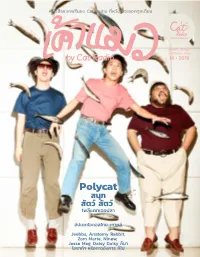

By Cat Radio 16 • 2019

หนังสือแจกฟรีของ Cat Radio ทีหวังว่าจะออกทุกเดือน่ แจกฟรี มีไม่เยอะ เก็บไว้เหอะ ...เมียว้ by Cat Radio 16 • 2019 Polycat สนุก สัตว์ สัตว์ โพลีแคทเจอปลา อัปเดตไอดอลไทย-เกาหลี Jeebbs, Anatomy Rabbit, Zom Marie, Ninew, Jesse Meg, Daisy1 Daisy ก็มา โอซาก้า หรือดาวอังคาร ก็ไป Undercover สืบจากปก by _punchspmngknlp คุณยาย บ.ก. ของเรา เสนอปกเล่มนี้ตอนทุกคนก�าลังยุ่งกับการ เตรียมงาน Cat Tshirt 6 แล้วอาศัยโอกาสลงมือท�าเลย จึงไม่มีโมเมนต์ การอภิปรายหรือเห็นชอบจากใคร อย่าได้ถามถึงความชอบธรรมใดๆ ว่า ท�าไมปกเค้าแมวกลับมาเป็นศิลปินชายอีกแล้ว (วะ) แต่ชีวิตไม่สิ้นก็ดิ้นกันไป เราได้เสนอปกรวมดาวไอดอลชุดแซนตี้ ช่วง คริสมาสต์ไปแล้ว เราสัญญาว่าเราจะไฟต์ ให้ก�าลังใจเราด้วย แต่ถ้าไม่ได้ก็ คือไม่ได้ จบ รักนะ (O,O) 2 3 เข้าช่วงท้ายของพุทธศักราช 2562 แล้ว เราจึงชวนวงดนตรีที่เพิ่งมีคอนเสิร์ตใหญ่ครั้งแรก 2 วงมาขึ้น ในฐานะผู้สังเกตการณ์ นับเป็นปีที่ ปกเค้าแมวฉบับเดียวกัน แม้จะต่างทั้งชั่วโมงบินในการท�างาน น่าชื่นใจของหลายศิลปินที่มีคอนเสิร์ต สไตล์ดนตรี สังกัด แต่เราคิดว่าทั้งคู่คงมีความสุขในการใช้เวลา ใหญ่/คอนเสิร์ตแรก ตลอดจนการไปเล่น ร่วมกับแฟนเพลงในคอนเสิร์ตเต็มรูปแบบของตนเอง รวมถึงการ CAT Intro ในเวที/เทศกาลดนตรีนานาชาติ หรือมี ท�าอะไรหลายอย่างที่น่าสนุกอย่างมาก พูดแบบกันเองก็สนุกสัสๆ RADIO ผลงานใดๆ ที่แฟนเพลงต่างสนับสนุน เราเลยจัดสัตว์มาถ่ายรูปขึ้นปกกับพวกเขาด้วยในคอนเซปต์ “สนุก อุดหนุน และภาคภูมิใจไปด้วย สัตว์ สัตว์” แต่อย่างที่เคยได้ยินกันว่าท�างานกับสัตว์ก็ไม่ง่าย ภาพ DJ Shift อาจเปรียบดังรางวัลหรือก�าลังใจ ที่ได้จึงมีทั้งสัตว์จริงและไม่จริง แต่กล่าวด้วยความสัตย์จริงว่าเรา จากการท�างานหนัก/ทุ่มเทให้สิ่งที่รัก สนุกกับการท�างานกับทั้งสองวง และหวังว่าบทสนทนาที่ปรากฏจะ -

17/9/15 Slagg Brothers Rhythm & Blues, Soul

17/9/15 Slagg Brothers Rhythm & Blues, Soul & Grooves Show Boys Keep Swinging 3:18 David Bowie From 1979 album Lodger Backslop 2:33 Baby Earl & The Trinidads 1958, has autobiographic elements - Berry was born at 2520 Goode Avenue in St. Johnny B. Goode 2:40 Chuck Berry Louis. He has written thirty more songs involving the character Johnny B. Goode, "Bye Bye Johnny", "Go Go Go", and "Johnny B. Blues" 1961. In 1962, the story continued with the arrival of Little Bitty Big John, learning Big Bad John 3:04 Jimmy Dean about his father's act of heroism. Big Bad John was also the title of a 1990 television movie starring Dean. 1966, written, composed, and performed by Cat Stevens. He got the name from his Matthew and Son 2:44 Cat Stevens tailor, Henry Matthews, who made suits him. From 1973 album Don't Shoot Me I'm Only the Piano Player. Donatella Versace named Daniel 3:55 Elton John her son Daniel Versace after this song. Hey Willy 3:28 The Hollies 1971. Hey Willy your mother calls you Billy, Your daddy calls you silly This was originally recorded by LA band The Leaves in 1965. No one has been able to Hey Joe 3:01 Tim Rose copyright it, so the song is considered "traditional," meaning anyone can record it without paying royalties. Hendrix was inspired to sing it after hearing this version. 1967. Original member Syd Barrett wrote this about a cross-dresser who used to Arnold Layne 2:53 Pink Floyd steal bras and panties from clotheslines in Cambridge. -

Diggin' You Like Those Ol' Soul Records: Meshell Ndegeocello and the Expanding Definition of Funk in Postsoul America

Diggin’ You Like Those Ol’ Soul Records 181 Diggin’ You Like Those Ol’ Soul Records: Meshell Ndegeocello and the Expanding Definition of Funk in Postsoul America Tammy L. Kernodle Today’s absolutist varieties of Black Nationalism have run into trouble when faced with the need to make sense of the increasingly distinct forms of black culture produced from various diaspora populations. The unashamedly hybrid character of these black cultures continually confounds any simplistic (essentialist or antiessentialist) understanding of the relationship between racial identity and racial nonidentity, between folk cultural authenticity and pop cultural betrayal. Paul Gilroy1 Funk, from its beginnings as terminology used to describe a specific genre of black music, has been equated with the following things: blackness, mascu- linity, personal and collective freedom, and the groove. Even as the genre and terminology gave way to new forms of expression, the performance aesthetic developed by myriad bands throughout the 1960s and 1970s remained an im- portant part of post-1970s black popular culture. In the early 1990s, rhythm and blues (R&B) splintered into a new substyle that reached back to the live instru- mentation and infectious grooves of funk but also reflected a new racial and social consciousness that was rooted in the experiences of the postsoul genera- tion. One of the pivotal albums advancing this style was Meshell Ndegeocello’s Plantation Lullabies (1993). Ndegeocello’s sound was an amalgamation of 0026-3079/2013/5204-181$2.50/0 American Studies, 52:4 (2013): 181-204 181 182 Tammy L. Kernodle several things. She was one part Bootsy Collins, inspiring listeners to dance to her infectious bass lines; one part Nina Simone, schooling one about life, love, hardship, and struggle in post–Civil Rights Movement America; and one part Sarah Vaughn, experimenting with the numerous timbral colors of her voice. -

08.14 | the Burg | 1 Community Publishers

08.14 | The Burg | 1 Community Publishers As members of Harrisburg’s business community, we are proud to support TheBurg, a free publication dedicated to telling the stories of the people of greater Harrisburg. Whether you love TheBurg for its distinctive design, its in-depth reporting or its thoughtful features about the businesses and residents who call our area home, you know the value of having responsible, community-centered coverage. We’re thrilled to help provide greater Harrisburg with the local publication it deserves. Realty Associates, Inc. Wendell Hoover ray davis 2 | The Burg | 08.14 CoNTeNTS |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| General and leTTers NeWS 2601 N. FroNT ST., SuITe 101 • hArrISBurg, PA 17101 WWW.TheBurgNeWS.CoM 7. NEWS DIGEST ediTorial: 717.695.2576 9. cHucklE Bur G ad SALES: 717.695.2621 10. cITy vIEW 12. state strEET PuBLISher: J. ALeX hArTZLer [email protected] COVER arT By: KrisTin KesT eDITor-IN-ChIeF: LAWrANCe BINDA IN The Burg www.KesTillUsTraTion.CoM [email protected] "The old Farmer's Almanac 2015 garden 14. from THE GrouND up Calendar, yankee Publishing Co." SALeS DIreCTor: LAureN MILLS 22. mIlestoNES [email protected] leTTer FroM THe ediTor SeNIor WrITer: PAuL BArker [email protected] “Nobody on the road/Nobody on the beach” BuSINess AccouNT eXeCuTIve: ANDreA Black More than once, I’ve thought of those lyrics [email protected] 26. fAcE of Business from Don henley’s 30-year-old song, “Boys 28. SHop WINDoW of Summer,” after a stroll down 2nd Street ConTriBUTors: or along the riverfront on a hot August day. It seems that everyone has left for TArA Leo AuChey, Today’S The day hArrISBurg the summer—to the shore, the mountains, [email protected] abroad. -

![[FW3T]⋙ the Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top by Dennis Munday](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4510/fw3t-the-jam-paul-weller-shout-to-the-top-by-dennis-munday-1254510.webp)

[FW3T]⋙ the Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top by Dennis Munday

The Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top Dennis Munday Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically The Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top Dennis Munday The Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top Dennis Munday The inside story of The Jam and The Style Council by the man who oversaw their careers! Record industry executive Dennis Munday's frank account reveals the trials and triumphs of Paul Weller's career, from The Jam's first single in 1977 to the break-up of The Style Council in 1989. He also writes about Weller's post-style Council solo career with a unique insight. Working for Polydor, the author became a regular presence at the two groups' many recording sessions, effectively becoming an honorary member of both The Jam and The Style Council. Despite a sometimes stormy relationship with the band members - and eventually leaving Polydor - Munday was the vital link between Paul Weller and his record company or years. Here then is a uniquely intimate portrait of a rock hero and two influential groups written by someone who was at the heart of the action. This new edition of Shout To The Top has been updated to include details of Paul's new album 22 Dreams, ongoing changes in the line-up to his band and the emergence of From The Jam, the group featuring Paul's former colleagues Bruce Foxton and Rick Buckler which is touring the world performing a set of Jam songs to great acclaim. Download The Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top ...pdf Read Online The Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top ...pdf Download and Read Free Online The Jam & Paul Weller: Shout to the Top Dennis Munday From reader reviews: Anna Lewis: In this 21st century, people become competitive in every single way. -

Marmalade at the Jam Factory

Marmalade at the Jam Factory Droylsden A collection of 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes ‘ A reputation built on solid foundations Bellway has been building exceptional quality new homes throughout the UK for over 75 years, creating outstanding properties in desirable locations. During this time, Bellway has earned a strong Our high standards are reflected in our dedication to reputation for high standards of design, build customer service and we believe that the process of quality and customer service. From the location of buying and owning a Bellway home is a pleasurable the site, to the design of the home, to the materials and straightforward one. Having the knowledge, selected, we ensure that our impeccable attention support and advice from a committed Bellway team to detail is at the forefront of our build process. member will ensure your home-buying experience is seamless and rewarding, at every step of the way. We create developments which foster strong communities and integrate seamlessly with Bellway abides by The the local area. Each year, Bellway commits Consumer Code, which is to supporting education initiatives, providing an independent industry transport and highways improvements, code developed to make healthcare facilities and preserving - as well as the home buying process creating - open spaces for everyone to enjoy. fairer and more transparent for purchasers. Over 75 years of housebuilding expertise and innovation distilled into our flagship range of new homes. Artisan traditions sit at the heart of Bellway, who refreshed and improved internal specification for more than 75 years have been constructing carefully marries design with practicality, homes and building communities. -

“Knowing Is Seeing”: the Digital Audio Workstation and the Visualization of Sound

“KNOWING IS SEEING”: THE DIGITAL AUDIO WORKSTATION AND THE VISUALIZATION OF SOUND IAN MACCHIUSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2017 © Ian Macchiusi, 2017 ii Abstract The computer’s visual representation of sound has revolutionized the creation of music through the interface of the Digital Audio Workstation software (DAW). With the rise of DAW- based composition in popular music styles, many artists’ sole experience of musical creation is through the computer screen. I assert that the particular sonic visualizations of the DAW propagate certain assumptions about music, influencing aesthetics and adding new visually- based parameters to the creative process. I believe many of these new parameters are greatly indebted to the visual structures, interactional dictates and standardizations (such as the office metaphor depicted by operating systems such as Apple’s OS and Microsoft’s Windows) of the Graphical User Interface (GUI). Whether manipulating text, video or audio, a user’s interaction with the GUI is usually structured in the same manner—clicking on windows, icons and menus with a mouse-driven cursor. Focussing on the dialogs from the Reddit communities of Making hip-hop and EDM production, DAW user manuals, as well as interface design guidebooks, this dissertation will address the ways these visualizations and methods of working affect the workflow, composition style and musical conceptions of DAW-based producers. iii Dedication To Ba, Dadas and Mary, for all your love and support. iv Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................. -

Ing the Needs O/ the 960.05 Music & Record Jl -1Yz Gî01axiï0h Industry Oair 13Sní1s CIL7.: D102 S3lbs C,Ft1io$ K.'J O-Z- I

Dedicated To Serving The Needs O/ The 960.05 Music & Record jl -1yZ GÎ01Axiï0H Industry OAIr 13SNí1S CIL7.: d102 S3lbS C,ft1iO$ k.'J o-z- I August 23, 1969 60c In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the SINGLE 1'1('It-.%" OE 111/î 11'1î1îA MY BALLOON'S GOING UP (AssortedBMI), 411) Atlantic WHO 2336 ARCHIE BELL AND WE CAN MAKE IT THE DRELLS IN THE RAY CHARLES The Isley Brotiers do more Dorothy Morrison, who led Archie Bell and the Drells Ray Charles should stride of their commercial thing the shouting on "0h Happy will watch "My Balloon's back to chart heights with on "Black Berries Part I" Day," steps out on her Going Up" (Assorted, BMI) Jimmy Lewis' "We Can (Triple 3, BMI) and will own with "All God's Chil- go right up the chart. A Make It" (Tangerine -blew, WORLD pick the coin well (T Neck dren Got (East Soul" -Mem- dancing entry for the fans BMI), a Tangerine produc- 906). phis, BMI) (Elektra 45671). (Atlantic 2663). tion (ABC 11239). PHA'S' 111' THE U lî lî /í The Hardy Boys, who will The Glass House is the Up 'n Adam found that it Wind, a new group with a he supplying the singing first group from Holland - was time to get it together. Wind is a new group with a for TV's animated Hardy Dozier - Holland's Invictus They do with "Time to Get Believe" (Peanut Butter, Boys, sing "Love and Let label. "Crumbs Off the It Together" (Peanut But- BMI), and they'll make it Love" (Fox Fanfare, BMI) Table" (Gold Forever, BMI( ter, BMI(, a together hit way up the list on the new (RCA 74-0228). -

Concrete: Art Design Architecture Education Resource Contents

CONCRETE: ART DESIGN ARCHITECTURE EDUCATION RESOURCE CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND BRIEFING 1.1 ABOUT THIS EXHIBITION 1.2 CONCRETE: A QUICK HISTORY 1.3 WHY I LIKE CONCRETE: EXTRACTS FROM THE CATALOGUE ESSAYS 1.4 GENERAL GLOSSARY OF CONCRETE TERMS AND TECHNOLOGIES 2 FOR TEACHERS 2.1 THIS EDUCATION RESOURCE 2.2 VISITING THE EXHIBITION WITH STUDENTS 3 FOR STUDENTS GETTING STARTED: THE WHOLE EXHIBITION ACTIVITIES FOR STUDENTS’ CONSIDERATION OF THE EXHIBITION AS A WHOLE 4 THEMES FOR EXPLORING THE EXHIBITION THEME 1. ART: PERSONAL IDENTITY: 3 ARTISTS: ABDULLAH, COPE, RICHARDSON THEME 2. DESIGN: FUNKY FORMS: 3 DESIGNERS: CHEB, CONVIC, GOODRUM THEME 3. ARCHITECTURE: OASES OF FAITH: 3 ARCHITECTS: MURCUTT, BALDASSO CORTESE, CANDALEPAS OTHER PERSPECTIVES: VIEWS BY COMMENTATORS FOLLOW EACH CONTRIBUTOR QUESTIONS, FURTHER RESEARCH AND A GLOSSARY FOLLOW ART AND DESIGN CONTRIBUTORS A COMMON ARCHITECTURE GLOSSARY FOLLOWS ARCHITECTURE: OASES OF FAITH 5 EXTENDED RESEARCH LINKS AND SOURCES IS CONCRETE SUSTAINABLE? 6 CONSIDERING DESIGN 6.1 JAMFACTORY: WHAT IS IT? 6.2 DESIGN: MAKING A MARK 6.3 EXTENDED RESEARCH: DESIGN RESOURCES 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cover: Candalepas Associates, Punchbowl Mosque, 2018 “Muqarnas” corner junction. Photo; Rory Gardiner Left: Candalepas Associates, Punchbowl Mosque, 2018 Concrete ring to timber dome and oculus. Photo: Rory Gardiner SECTION 1 1.1 About this exhibition BACKGROUND BRIEFING CONCRETE: ART DESIGN ARCHITECTURE presents 21 exciting concrete projects ranging from jewellery to skateparks, hotel furniture, public sculptures, mosques and commemorative paving plaques. All 21 artists designers and architects were selected for their innovative technical skills and creative talents. These works show how they have explored concrete’s versatility by pushing its technical boundaries to achieve groundbreaking buildings, artworks and design outcomes. -

Jam Factory Statement

The new Jam Factory: a new district to drive the local economy. The Jam Factory centre in Chapel Street is set to become a new district in the heart of South Yarra as part of a comprehensive proposal to redevelop and revitalise the site. Subject to planning approval, the site will be opened up with a network of laneways and a vibrant public realm. A major economic catalyst, the Jam Factory will be a destination that resonates with the community and drives the local economy. The plans, lodged with the City of Stonnington by Newmark Capital, will see the new Jam Factory become a world-class office, entertainment, dining, retail, and cultural district, setting a new standard in sophisticated mixed use development. Newmark Joint Managing Directors Chris Langford and Simon T. Morris said that the proposal is the first step towards realising the company’s vision for the area. “As long-term locals ourselves, our desire is to restore the status of the Jam Factory and Chapel Street, with authenticity, creativity, and community at its core,” Mr Langford said. “Our vision is to revitalise the Jam Factory, while respecting and celebrating its rich character and history. “This site will be a district that encompasses the needs of the whole community. It will be a permeable district in the heart of Melbourne’s most desirable location. “One of the ways we are opening up the site is by reinstating the laneways that originally ran through the Jam Factory, similar to that when the site was occupied by the Red Cross Preserving Company.