Everyday Talk and Ideology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Nichole Rustin's CV

Nichole Rustin-Paschal, Ph.D., J.D. [email protected] Division of Liberal Arts Rhode Island School of Design 2 College St. Providence, RI 02903 EDUCATION: UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA SCHOOL OF LAW, J.D. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, Ph.D. American Studies AMHERST COLLEGE, B.A. Interdisciplinary Studies, magna cum laude PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS: African American Cultural History; Gender Studies; Critical Race Feminism; Law PUBLICATIONS: BOOKS • Art Law: Framing a Critique of Justice in Contemporary Art and Culture (in progress) • The Kind of Man I Am: Jazzmasculinity and the World of Charles Mingus Jr. (Wesleyan University Press, 2017) o Nominated for 2018 Association for Recorded Sound Collections Award for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research EDITED VOLUME • Oxford Handbook of Jazz and Gender (Oxford University Press, in progress) CO-EDITED VOLUMES • The Routledge Companion to Jazz Studies, co-editor with Nicholas Gebhardt and Tony Whyton (Routledge University Press, 2019) • Big Ears: Listening for Gender in Jazz Studies, co-editor with Sherrie Tucker (Duke University Press, 2008) ARTICLES • “You Won’t Forget Me: Miles Davis and the Gendered Silence of Influence in Jazz,” in Miles Davis Beyond Jazz: 1971-1991, eds. Roger Fagge, Nicolas Pillai, and Tim Wall (Oxford University Press, under contract) • “The Reason I Play the Way I Do Is: Jazzmen, Emotion, and Creating in Jazz,” Routledge Companion to Jazz Studies, eds. Nicholas Gebhardt, Nichole Rustin-Paschal, and Tony Whyton (Routledge University Press, 2019). N. Rustin-Paschal 1 • “Self Portrait: On Emotion and Experience as Useful Categories of Gender Analysis in Jazz History,” in Jazz Debates/Jazzdebatten, edited by Wolfram Knauer. -

Inquest Into the Death of Kerri Anne Pike, Peter Michael Dawson and Tobias John Turner

CORONERS COURT OF QUEENSLAND FINDINGS OF INQUEST CITATION: Inquest into the death of Kerri Anne Pike, Peter Michael Dawson and Tobias John Turner TITLE OF COURT: Coroners Court of Queensland JURISDICTION: CAIRNS FILE NO(s): 2017/4584, 2017/4582 & 2017/4583 DELIVERED ON: 30 August 2019 DELIVERED AT: Cairns HEARING DATE(s): 6 August 2018, 26-30 November 2018 FINDINGS OF: Nerida Wilson, Northern Coroner CATCHWORDS: Coroners: inquest, skydiving multiple fatality; Australian Parachute Federation; Commonwealth Aviation Safety Authority; Skydive Australia; Skydive Cairns; solo sports jump; tandem; relative work; back to earth orientation; premature deployment of main chute; container incompatibility with pack volume; reserve chute; automatic activation device (AAD); consent for relative work; regulations; safety management system; drop zone; standardised checking of sports equipment; recommendation for sports jumpers to provide certification for new or altered sports rigs including compatibility of main chute to container; recommendation to introduce 6 month checks by DZSO or Chief Instructor for sports rigs at drop zones to ensure compatibility. REPRESENTATION: Counsel Assisting: Ms Melinda Zerner i/b Ms Melia Benn Family of Kerri Pike: Ms Rachelle Logan i/b Ms Klaire Coles, Caxton Legal Centre Inc Family of Tobias Turner: Dr John Turner and Mrs Dianne Turner Skydive Cairns: Mr Ralph Devlin QC and Mr Robert Laidley i/b Ms Laura Wilke, Moray and Agnew Lawyers Civil Aviation Safety Mr Anthony Carter, Special Counsel Authority: Australian Parachuting -

The Salience of Race Versus Socioeconomic Status Among African American Voters

the salience of race versus socioeconomic status among african american voters theresa kennedy, princeton university (2014) INTRODUCTION as majority black and middle class; and Orange, New ichael Dawson’s Behind the Mule, published Jersey as majority black and lower class.7 I analyzed in 1994, examines the group dynamics and the results of the 2008 presidential election in each identity of African Americans in politics.1 of the four townships, and found that both majority MDawson gives blacks a collective consciousness rooted black towns supported Obama at rates of over 90 per- in a history of slavery and subsequent economic and cent.8 The majority white towns still supported Obama social subjugation, and further argues that African at high rates, but not as high as in the majority black Americans function as a unit because of their unique towns.9 I was not surprised by these results, as they shared past.2 Dawson uses data from the 1988 National were in line with what Dawson had predicted about Black Election Panel Survey to analyze linked fate— black group politics.10 However, I was unable to find the belief that what happens to others in a person’s more precise data than that found at the precinct level, racial group affects them as individual members of the so my results could not be specified to particular in- racial group—and group consciousness among blacks dividuals.11 in the political sphere, and then examines the effects The ecological inference problem piqued my in- of black group identity on voter choice and political terest in obtaining individual data to apply my find- leanings. -

The Double Bind: the Politics of Racial & Class Inequalities in the Americas

THE DOUBLE BIND: THE POLITICS OF RACIAL & CLASS INEQUALITIES IN THE AMERICAS Report of the Task Force on Racial and Social Class Inequalities in the Americas Edited by Juliet Hooker and Alvin B. Tillery, Jr. September 2016 American Political Science Association Washington, DC Full report available online at http://www.apsanet.org/inequalities Cover Design: Steven M. Eson Interior Layout: Drew Meadows Copyright ©2016 by the American Political Science Association 1527 New Hampshire Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-878147-41-7 (Executive Summary) ISBN 978-1-878147-42-4 (Full Report) Task Force Members Rodney E. Hero, University of California, Berkeley Juliet Hooker, University of Texas, Austin Alvin B. Tillery, Jr., Northwestern University Melina Altamirano, Duke University Keith Banting, Queen’s University Michael C. Dawson, University of Chicago Megan Ming Francis, University of Washington Paul Frymer, Princeton University Zoltan L. Hajnal, University of California, San Diego Mala Htun, University of New Mexico Vincent Hutchings, University of Michigan Michael Jones-Correa, University of Pennsylvania Jane Junn, University of Southern California Taeku Lee, University of California, Berkeley Mara Loveman, University of California, Berkeley Raúl Madrid, University of Texas at Austin Tianna S. Paschel, University of California, Berkeley Paul Pierson, University of California, Berkeley Joe Soss, University of Minnesota Debra Thompson, Northwestern University Guillermo Trejo, University of Notre Dame Jessica L. Trounstine, University of California, Merced Sophia Jordán Wallace, University of Washington Dorian Warren, Roosevelt Institute Vesla Weaver, Yale University Table of Contents Executive Summary The Double Bind: The Politics of Racial and Class Inequalities in the Americas . -

The Myths That Make Us: an Examination of Canadian National Identity

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-29-2019 1:00 PM The Myths That Make Us: An Examination of Canadian National Identity Shannon Lodoen The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Plug, Jan The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Gardiner, Michael The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Shannon Lodoen 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Rhetoric Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Recommended Citation Lodoen, Shannon, "The Myths That Make Us: An Examination of Canadian National Identity" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6408. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6408 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis uses Barthes’ Mythologies as a framework to examine the ways in which the Canadian nation has been mythologized, exploring how this mythologization affects our sense of national identity. Because, as Barthes says, the ultimate goal of myth is to transform history into nature, it is necessary to delve into Canada’s past in order to understand when, why, and how it has become the nation it is today. This will involve tracing some key aspects of Canadian history, society, and pop culture from Canada’s earliest days to current times to uncover the “true origins” of the naturalized, taken-for-granted elements of our identity. -

1 in the United States District Court for the Southern

Case 1:11-cv-00110-CG-M Document 54 Filed 09/13/12 Page 1 of 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA SOUTHERN DIVISION MICHAEL DAWSON, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) CIVIL NO. 11-0010-CG-M v. ) ) KATINA R. QUAITES, ) ) Defendant MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER ON SUMMARY JUDGMENT This matter is before the court on the unopposed motion for summary judgment filed by the plaintiff, Michael Dawson (“Dawson”). (Doc. 50). Dawson seeks summary judgment on his state law claims for assault and battery, outrage, and negligence against the defendant, Katina Quaites (“Quaites”). For the reasons stated below, Dawson’s motion is GRANTED IN PART and DENIED IN PART. FACTUAL BACKGROUND Because Dawson’s motion is unopposed, the court adopts the undisputed facts described in the motion and accompanying affidavit. (Doc. 50 and Doc. 50-1). Dawson is employed as a police officer for the City of Daphne, Alabama. (Doc. 50-1 at 1). Like many Daphne police officers, Dawson frequently “moonlights” as a security guard when he is off-duty. Id. On the evening of May 27, 2009, Dawson was working as a security guard at 1 Case 1:11-cv-00110-CG-M Document 54 Filed 09/13/12 Page 2 of 8 Dillard’s Department Store in the Eastern Shore Center in Spanish Fort, Alabama, when store employees reported to him that they saw Quaites behaving unusually, and suspected her of stealing a dress. Id. at 2. Specifically, the employees saw Quaites take two dresses off of a clothing rack and go into the women’s changing room. -

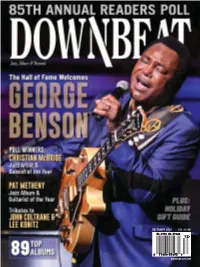

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

HOBOKEN PICTORIAL Str«*T 2Nd Class Postage Paid VOLUME 11 NO

HOBOKEN PICTORIAL Str«*t 2nd Class Postage Paid VOLUME 11 NO. 26 .-070SO THURSDAY, AUGUST 28, 1969 Ai Hobokrn, N. J. TEN CENTS HtS mother-in-law moved in ON HONEYMOON CONSTRUCTION NEARS with Mm. That's not too bad but NUPTIAL VOWS EXCHANGED the ruults had him dizzy. He ON OIL PLANT souk" 1't smoke in his own home. She objected to him reading the It is expected that within • paper in the living room. She month's time, initial dictated policy as to the daily construction on Supermarine's 40 million oil processing facility fnenu. Had all the neighbors will begin. It will straddle the jp-in arim with her complaints Weehawken-Hoboken boundary •gainst their cats and dogs. He line on the site of the Todd was in a dilemma as to just how Shipyard. to solve this problem. His wife Charles Krause, former inderstood but she had been Weehawken mayor and attorney tominatad all her life by her for the oil company said the nother. The mother-irvtow engineering work and plans have somptained so much about the been completed and submitted for approval. prden in the backyard that he Construction will be on the tired a gardener to take care of portion of the shipyard which tie lawn. Never would he believe Supermarine purchased from the t. but this did it. The U. S General Services nother-in-tew being a widow and Administration last March. Part he gardener being a widower, of the area is in Weehawken and hey had a common ground for STELLA MARIS CHURCH in part in Hoboken. -

Learning from Ambiguously Labeled Images

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Technical Reports (CIS) Department of Computer & Information Science January 2009 Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Timothee Cour University of Pennsylvania Benjamin Sapp University of Pennsylvania Chris Jordan University of Pennsylvania Ben Taskar University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports Recommended Citation Timothee Cour, Benjamin Sapp, Chris Jordan, and Ben Taskar, "Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images", . January 2009. University of Pennsylvania Department of Computer and Information Science Technical Report No. MS-CIS-09-07 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports/902 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Abstract In many image and video collections, we have access only to partially labeled data. For example, personal photo collections often contain several faces per image and a caption that only specifies who is in the picture, but not which name matches which face. Similarly, movie screenplays can tell us who is in the scene, but not when and where they are on the screen. We formulate the learning problem in this setting as partially-supervised multiclass classification where each instance is labeled ambiguously with more than one label. We show theoretically that effective learning is possible under reasonable assumptions even when all the data is weakly labeled. Motivated by the analysis, we propose a general convex learning formulation based on minimization of a surrogate loss appropriate for the ambiguous label setting. We apply our framework to identifying faces culled from web news sources and to naming characters in TV series and movies. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology. -

Making Martin Luther King Jr's Dream Come Alive

Making Martin Luther King Jr’s Dream Come Alive the Success Story of the Parkway Homes/ Parkway Gardens Community: By: Riley Wentzler & Felicia Barber Greenburgh is proud to have one of the largest middle class African American Communities in The United States. It’s possible it could be the largest. Two neighborhoods: Parkway Homes and Parkway Gardens have been home to some very famous residents. Cab Calloway (1907-1994): Cab Calloway was a famous jazz singer and musician. Cab Calloway was born on December 25th, 1907 in Rochester, New York. He spent his childhood in Baltimore Maryland, before moving to Chicago Illinois to study law at Crane College. His heart was never really in it however, his true passion was singing. He frequently performed at Chicago’s famous Sunset Club as part of The Alabamians. After meeting Louis Armstrong and learning the style of scat singing, he dropped out of law school, left Chicago, and moved to New York to pursue a full-time career as a singer. In 1930, Cab Calloway and his Orchestra were regular performers at one of the most popular clubs in New York, Harlem’s Cotton Club. His most famous song, which sold more than one million copies, is “Minnie the Moocher” (1931) (https://www.biography.com/people/cab-calloway-9235609). In 1955, he moved to Greenburgh and settled into a 12 room House on Knollwood Avenue. While there, he performed in the famous opera, “Porgy and Bess” (https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/14/nyregion/nyregionspecial2/14cabwe.html). He received the National Medal of the Arts in 1993 and died a year later in Hockessin, Delaware (https://www.biography.com/people/cab-calloway-9235609).