The Kansas Relays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIG 12 OUTDOOR CHAMPIONSHIP May 14-16, 2021 | R.V

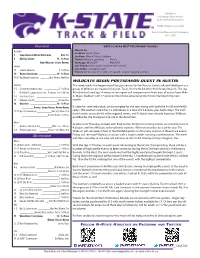

K-STATE TRACK AND FIELD BIG 12 OUTDOOR CHAMPIONSHIP May 14-16, 2021 | R.V. Christian Track | Manhattan, Kan. 2020-21 OUTDOOR SCHEDULE MEET PREVIEW MEET SCHEDULE The Kansas State track and field teams will host Friday’s Event Schedule UTSA Invitational the 24th Big 12 Outdoor Championship this Mar. 18-20 11:00 a.m. ............................Combined Events Begin weekend on Friday, May 14 through Sunday, May 12:00 p.m. ......................................Field Events Begin San Antonio, Texas 16 at R.V. Christian Track and Field Complex. This 8:15 p.m. ........................................Track Events Begin will be the third time in Big 12 history that the Wildcats will host the outdoor contest, with the Shocker Invitational other two events taking place during the 2005 Saturday’s Event Schedule Mar. 26-27 and 2012 seasons. 10:00 a.m. ...........................Combined Events Begin Wichita, Kan. 2:00 p.m. .......................................Field Events Begin 3:00 p.m. ......................................Track Events Begin NOTES Jim Click Combined Events Sunday’s Event Schedule Apr. 8-9 Conference Leaders | 1:00 p.m. ........................................Field Events Begin This weekend, R.V. Christian Track and Field 3:00 p.m. ......................................Track Events Begin Tuscon, Ariz. Complex will be the home of the best athletes from around the conference. To power past the 7:00 p.m. ........................Team Trophy Presentation rest of the Big 12, K-State will need to rely on a Jim Click Invitational handful of athletes who have garnered top marks Apr. 10 in the conference this outdoor season, including Tejaswin Shankar (2.25m, High Jump), Lauren Times are an approximation Tucson, Ariz. -

Kstatenotes052213 KSU Track Notes

- Erik Kynard - 2012 Olympic Silver Medalist Back-to-Back NCAA Champion 9 NCAA Champions since 2000 Back-to-Back Women’s Big 12 Champions 2001 • 2002 INDOOR WEEK 10: NCAA WEST PRELIMINARY ROUNDS May 23-25 DECEMBER Location: Austin, Texas 7 CAROL ROBINSON WINTER PENTATHLON ______DICK: 1ST Stadium: Mike A. Myers Stadium 8 KSU ALL-COMERS ______________11: 1ST PLACE Twitter: @kstate_gameday @ncaa ____________GIBBS/WILLIAMS: SCHOOL RECORDS Hashtags: #KStateTF #NCAATF JANUARY Live Results: texassports.com/livestats/c-track/ Live Video: texassports.com 11 JAYHAWK CHALLENGE ________________8: 1ST PLACE Tickets: All-Session: $25 adult, $15 (youth, senior); Single-Day: $10/7 19 WILDCAT INVITATIONAL ____________18: 1ST PLACE 24-26 BILL BERGAN INVITATIONAL ______MEN, WOMEN: 3RD PLACE WILDCATS BEGIN POSTSEASON QUEST IN AUSTIN FEBRUARY This week marks the beginning of the postseason for the Kansas State track and field team as a 1-2 SEVIGNE HUSKER INVITATIONAL __________1: 1ST PLACE group of Wildcats are headed to Austin, Texas, for the NCAA West Preliminary Rounds. The top 8 DON KIRBY COLLEGIATE INVITATIONAL RODRIGUEZ: SCHOOL RECORD 48 individuals and top 24 relays in the region will compete over three days of action from Mike 8-9 IOWA STATE CLASSIC ______________________ A. Myers Stadium with 12 spots on the line to advance to the NCAA Championship next 15 NEBRASKA TUNE-UP________________LINCOLN, NEB. month. 16 KSU OPEN __________________18: 1ST PLACE ________KYNARD: SCHOOL RECORD, AHEARN RECORD K-State has nine individuals set to compete for the men along with both the 4x100 and 4x400 relays. The women’s team has 12 individuals in a total of 14 entries, plus both relays. -

1993 Northern Iowa Track and Field (Men's)

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Athletics Media Guides Athletics 1993 1993 Northern Iowa Track and Field (Men's) University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1993 Athletics, University of Northern Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Northern Iowa, "1993 Northern Iowa Track and Field (Men's)" (1993). Athletics Media Guides. 193. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/amg/193 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Athletics Media Guides by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. nspirelJ- ----Performance 1992 CROSS COUNTRY RESULTS orthern Iowa, in its second year Nas a member of the Missouri Valley Conference, won t~e men's cross country championship October 31 in Normal, Ill. UNI coach Chris Bucknam received MVC Coach of the Year honors while the Panthers had three runners earn all-conference honors. Senior Marty Greene finished second to three-time champ Mornay Annandale of Wichita State. Teammates Jason Meyer and Jeff Joiner finished fifth and ninth, respectively. The Panthers, picked to finish second behind host Illinois State in the pre-meet poll, tallied 53 points in the final standings while ISU took second with 69 and Southwest Missouri State had 73. Northern Iowa's 1992 Missouri Valley Conference Cross Country Champions Bradley Invitational 9. Jason Meyer 25:36 Iowa State Classic UNI Finishers (SK) 14. -

2016 NCAA Division I Outdoor Qualifying (FINAL) 100M RANK ATHLETE YEAR TEAM TIME MEET MEET DATE WIND

6/21/2016 TFRRS June 21 2016 • 02:59 PM • www.tfrrs.org 2016 NCAA Division I Outdoor Qualifying (FINAL) 100m RANK ATHLETE YEAR TEAM TIME MEET MEET DATE WIND 1 Akinosun, Morolake SR4 Texas 10.97 LSU Alumni Gold 04/23/16 3.5 2 Cunliffe, Hannah SO2 Oregon 10.99 Mt. SAC Relays 04/14/16 1.7 3 Henderson, Ashley SO2 San Diego St. 11.01 Mountain West Championships 05/11/16 4 4 Carter , Destiny JR3 Kentucky 11.11 LSU Invitational 04/30/16 3.8 5 Gray, Kianna FR1 Kentucky 11.12 LSU Invitational 04/30/16 3.8 6 Sanders, Shayla JR3 Florida 11.13 Power Conference Cardinal & Gold 03/25/16 1.2 6 Johnson, Kortnei FR1 LSU 11.13 LSU Invitational 04/30/16 3.8 8 Oliver, Javianne JR3 Kentucky 11.16 LSU Invitational 04/30/16 3.8 9 Jefferson, Kyra JR3 Florida 11.17 UF Tom Jones Memorial 04/22/16 0.2 9 Brisco, Mikiah SO2 LSU 11.17 LSU Alumni Gold 04/23/16 3.5 11 Washington, Ariana FR1 Oregon 11.18 Pac12 Outdoor Track & Field Championships 05/14/16 1.4 11 DavisWhite, Kali JR3 Tennessee 11.18 LSU Alumni Gold 04/23/16 3.5 13 Stevens, Deajah SO2 Oregon 11.19 Pac12 Outdoor Track & Field Championships 05/14/16 1.3 14 Todd, Jasmine JR3 Oregon 11.20 Mt. SAC Relays 04/14/16 1.7 15 Gaither, Tynia SR4 USC 11.21 UCLA vs. -

Kansas Relays Friday, April 19, 2013 Field Events 8:00 Am – Javelin 8

Kansas Relays Friday, April 19, 2013 Field Events 8:00 am – Javelin – John Blazevic, Ryan Ahlgren – ride with parents 8:00 am – Girls shot – Courtney Caresia – ride with Coach Daniels 9:30 am – Girls pole vault – Allison Meads – ride with parents 11:00 am – Girls triple jump – Whitney Nelson – ride w/Coach Evans – leave OE at 9:00 5:30 pm – Girls high jump – Whitney Nelson – already there Running Events 9:15 am – Boys 110 Hurdles – AJ Stephens and Adam Osheim – ride with parents – be there by 7:45 or earlier 11:25 am – Girls 100 – Jasmine Thomas – ride with parents – be there by 9:45 1:20 pm – Boys 300 Hurdles – AJ Stephens – already there 1:40 pm – Girls 300 Hurdles – Harris sisters – be at OE by 11:00 – leave at 11:15 – ride in a school van 2:05 pm – Girls distance medley – Riley Gay, Valencia Hinton-Scott, Natalie Kopplin, Brenna McDannold – be at OE by 11:00 – ride the 11:15 van with 300 hurdle girls (Kelsey Quiring – alt – will be at KU by 1:00 pm) 3:35 pm – Girls 4X100 Relay – Ryan Beard, Taiylor Sharp, Ali Bland, Jasmine Thomas (Drue Bailey – alt) – be at OE by 12:45 – leave at 1:00 – school van 3:55 pm – Boys 4X100 Relay – DaJuane Box, Parker Evans, Kyle Evans, Caleb White (Jalen Branson – alt) – be at OE by 12:45 – leave at 1:00 – school van 4:45 pm – Girls 800 – Kelsey Quiring – already there 7:25 pm – Girl 4X400 Relay – Valencia Hinton-Scott, Drue Bailey, N’Dia Harris, Kelsey Quiring (Ali Bland – alt) – all wil be there already 7:55 – Boys 4X400 Relay – Kyle Evans, Nick Hinrichs, Braxton Love, Parker Evans (Sam Wood – alt) – Nick, Braxton, Sam – will pick up at OE at 5:00 pm if you don’t rides Saturday, April 20, 2013 Running Events 8:20 am – Boys Sprint Medley Relay – DaJuane Box, Kyle Evans, Parker Evans, Nick Hinrichs – We will leave OE at 6:30 – school van – Be sure to eat before you come to school. -

Women's Outdoor -All-Time List

Michigan High School Alumni - Women's Outdoor -All-time List Updated 6-16-2020 50 METERS 6.27# Shayla Mahan (Detroit Mumford-South Carolina) Newcastle/City Games (1.0) (150m) ......... 9/15/2012 100 METERS 11.17 Kyra Jefferson (Detroit Cass Tech-Florida) Gainesville/Jones Memorial (0.4) ............. 4/22/2017 11.20 Shayla Mahan (Detroit Mumford-South Carolina) Columbia/Baskin (1.5) ............................... 3/26/2011 11.25 Anavia Battle (Wayne Memorial-Ohio St) Columbia/Gamecock Inv (1.9) .................. 4/13/2019 11.28 Jefferson (Florida) Tuscaloosa/SEC (h) (0.5) ......................... 5/13/2016 11.28 Jefferson (Florida) Tuscaloosa/SEC (-0.2) .............................. 5/14/2016 11.31 Mahan (South Carolina) Greensboro/Peace & Freedom (1.5) ........ 4/19/2008 11.31 Mahan (South Carolina) Greensboro/NCAA East (h) (1.1) .............. 5/27/2010 11.32 Battle (Ohio St) Iowa City/Big 10 (0.3) ................................ 5/12/2019 11.34 Mahan (South Carolina) Greensboro/NCAA East (q) (1.1) .............. 5/28/2010 11.35 Mahan (South Carolina) Myrtle Beach (1.7) ..................................... 3/19/2011 11.35 Mahan (South Carolina) Gainesville (1.2) ......................................... 4/ 6/2012 11.35 Mahan (South Carolina) Brazzaville (1.6) ........................................ 6/10/2012 11.37 Mahan (Detroit Mumford HS) Jackson/Midwest Meet (1.7) ...................... 6/ 9/2007 11.37 Ashlee Abraham (Detroit Renaissance-Ohio St) Jacksonville/NCAA East (h) (1.7) ............. 5/23/2013 11.37 Battle (Ohio St) Gainesville/Florida Relays (-0.1) ............... 3/29/2019 11.38 Mahan (Detroit Mumford HS) Indianapolis/USATF Juniors (0.0) ............. 6/21/2007 11.39 Mahan (South Carolina) Columbus (1.3) ........................................ -

Kansas Relays Schedule

2014 KANSAS RELAYS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, APRIL 16 FRIDAY, APRIL 18 SATURDAY, APRIL 19 Combined Events Field Events Field Events 10:00 am Decathlon - 100 meters Men 8:00 am Javelin (Memorial Stadium) Girls 9:00 am Shot Put Girls 10:30 am Heptathlon - 100 meter hurdles Women 8:00 am Discus Women 9:00 am Pole Vault Boys 10:45 am Decathlon - Long Jump Men 9:00 am Pole Vault Girls 9:00 am High Jump Girls 11:15 am Heptathlon - High Jump Women 9:00 am High Jump Boys 9:00 am Shot Put Boys 12:00 pm Decathlon - Shot Put Men 9:00 am Triple Jump Girls 9:00 am Javelin Boys 9:00 am Long Jump Girls 1:15 pm Heptathlon - Shot Put Women 9:00 am Triple Jump Boys 9:00 am Long Jump Boys 1:30 pm Decathlon - High Jump Men 11:30 am Discus (Memorial Stadium) Boys 1:30 pm Shot Put Women 2:30 pm Heptathlon - 200 meters Women 11:30 pm Javelin Men 1:30 pm Shot Put Men 3:30 pm Decathlon - 400 meters Men 1:00 pm Pole Vault Women 1:30 pm Javelin Women 1:00 pm High Jump Women 1:30 pm Pole Vault Men THURSDAY, APRIL 17 1:00 pm Triple Jump Women 1:30 pm Long Jump Women 1:00 pm Triple Jump Men 1:30 pm Long Jump Men 3:00 pm Discus (Memorial Stadium) Girls 1:30 pm High Jump Men Combined Events 3:00 pm Discus Men Running Events 9:00 am Decathlon - 110 meter hurdles Men 6:00 pm Downtown Shot Put Elite Men 9:00 am Heptathlon - Long Jump Women 8:00 am Sprint Medley relay Girls 8:16 am Sprint Medley relay Boys 9:45 am Decathlon - Discus Men Running Events 10:15 am Heptathlon - Javelin Women 8:31 am 4x200 meter relay Girls 9:00 am 4xMile relay Girls 8:46 am 4x200 meter relay Boys 11:00 -

2009 Kansas Relays Schedule

2010 KANSAS RELAYS SCHEDULE Tentative Schedule Decathlon / Heptathlon Wednesday, April 14 Thursday, April 15 10:00 AM Decathlon 100 Meter Dash 8:30 AM Decathlon 110 Meter Hurdles 10:30 AM Heptathlon 100 Meter Hurdles 9:00 AM Heptathlon Long Jump 10:45 AM (approx.) Decathlon Long Jump 9:15 AM (approx.) Decathlon Discus 11:15 AM (approx.) Heptathlon High Jump 10:40 AM (approx.) Heptathlon Javelin 12:35 PM (approx.) Decathlon Shot Put 11:15 PM (approx.) Decathlon Pole Vault 1:45 PM (approx.) Heptathlon Shot Put 12:30 PM (approx.) Heptathlon 800 Meters 2:25 PM (approx.) Decathlon High Jump 3:00 PM (approx.) Decathlon Javelin 3:15 PM (approx.) Heptathlon 200 Meter Dash 4:20 PM (approx.) Decathlon 1500 Meters 4:30 PM (approx.) Decathlon 400 Meter Dash _____________________________________________ Thursday, April 15 Hammer Events ___________________________________________ 12:00 PM Men's Hammer Throw Friday, April 16 4:30 PM Women’s Hammer Throw Field Events Continued 3:00 PM Men’s Shot Put Running Events Men's Triple Jump 5:00 PM Women’s Unseeded 800m Run Boy’s Triple Jump 5:20 PM Men’s Unseeded 800m Run 5:30 PM Boy’s Pole Vault 5:40 PM Women’s Unseeded 1500m Run Girl's High Jump 6:00 PM Men’s Unseeded 1500m Run Men’s Javelin 6:20 PM Men’s Unseeded 3000m Steeple 6:30 PM Boy’s Shot Put 6:35 PM Women’s 3000m Run (F) 6:50 PM Women’s 5000 Meter Run (F) Running Events 7:15 PM Men’s 5000 Meter Run (F) OPENING CEREMONY AND NATIONAL ANTHEM 7:35 PM Women’s 10,000 Meter Run (F) 8:00 AM Girl’s 4 Mile Relay (F) 8:20 PM Men’s 10,000 Meter Run (F) 8:30 AM -

Men's 100 Meters

2014 NCAA Division I Outdoor Track & Field Championships as of 6/6/2014 11:29:26 AM Men's 100 Meters ALL-TIME BESTS World Usain BOLT 86 Jamaica JAM 9.58 (0.9) 8/16/2009 Berlin, Germany 12th IAAF World Championships i Collegiate Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 87 Florida State ZIM 9.89 (1.3) 6/10/2011 Des Moines, Iowa NCAA Division I Outdoor Champio NCAA Meet Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 87 Florida State ZIM 9.89 (1.3) 6/10/2011 Des Moines, Iowa NCAA Division I Outdoor Champio SEASON LEADERS World (o) Justin GATLIN 82 United States USA 9.87 5/21/2014 Beijing, China IAAF World Challenge Beijing Collegiate (o) Trayvon BROMELL FR 95J Baylor USA 10.01q (1.5) 3/29/2014 Austin, Texas Texas Relays REIGNING CHAMPS NCAA (o) Charles SILMON SR 91 TCU USA 9.89w (3.2) 6/7/2013 Eugene, Ore. Rank Athlete Institution/Hometown Qual. Best (raw mark) Outdoor PR NCAA 2013 Conf. Finish Justin WALKER SR Northwestern State USA 9.95w w: 2.5 10.16 (18) Southland (1) 1 90 Slidell, La. 5/9 Southland Conference Trac 9.95w Trayvon BROMELL FR Baylor USA 10.01 w: 1.5 10.01 Big 12 (1) 2 95J St. Petersburg, Fla. 3/26 2014 Clyde Littlefield Texas 9.77w Dentarius LOCKE SR Florida State USA 10.03w w: 2.6 9.96 (2) ACC (1) 3 89 Tampa, Fla. 5/31 NCAA Championships (Prel 9.91 10.16 Clayton VAUGHN JR UT Arlington USA 10.08w w: 3.1 10.13 Sun Belt (1) 4 92 Sulphur Springs, Texas 5/9 Sun Belt Conference Outdo 10.11w John TEETERS SO Oklahoma State USA 10.11w w: 2.7 10.14 Big 12 (3) 5 93 Edmond, Okla. -

Of the Shrew

THE DAILY NEBRASKAN mile relay. Noble, Lloyd, Layton and HUSKER ATHLETES Trexler will rrobably run "in the 880-yar- d utSerdkug CO. ' relay, while Baldwin will sup- The Genuine 1321 O Street plant Layton in the 440 yard Corn TO LEAVE TODAY relay team. The two MEN! PLACE TO BUY husker sprint THE Nebraska sprint teams should place any Drugs FOR DRAKE MEET high In the Drake mete.barrlng bad brenks, as the only team that Tom Wye Coats Drug Sundries defeated them at the Kansas Relays, " team, Toilet Articles Second Squad of Nebraska Track the Jayhawker sprint relay Men Will Depart at One will not ho present at the Drake Cigars O'clock Over the classic. The K. U. relay teams are Candies Rock Island. running at the Penn relays Saturday. Penn Relays. Kodaks MANAGER KING IN CHARGE Pennsylvania's Relay Race Carni- Magazines val, the classic track and field meet- Cornhusker Teams Expected to ing of the year and the greatest track good Make Strong Fight for High any place in the We specialize on all and field meet held Honors in Des Moines better, Soda Fountain Specialties orld annually, ill be bigger, Classic. up to a higher at our more brilliant and Meet your friends standard than ever before. Oxford Thesecoml stove. Use our telephone squad of Cornhusker University, England, ill run in the directory. Buy trackstcrs who will and city compete in the distance medley relay championship stamps here. We Drake Relays at Des postage Moines Satur- on Friday, the 27th, the first day of your patronage day will appreciate leave at 1 o'clock today meet and in the two mile relay you to feel at over the and want the Rock Island, arriving at the championship on Saturday, Morgan of our store. -

KANSAS 100 Meters 3,000-Meter Steeplechase 400-Meter Relay 10.07 Laverne Smith, Big Eight Championships 1976 8:28.54 Kent Mcdonald, AAU 1975 39.39 (L

MEN’S OUTDOOR ALL-TIME TOP PERFORMERS TRACK & FIELD • As of 6/8/13 • KANSAS 100 Meters 3,000-Meter Steeplechase 400-Meter Relay 10.07 Laverne Smith, Big Eight Championships 1976 8:28.54 Kent McDonald, AAU 1975 39.39 (L. Smith, A. Coleman, C. Wiley, L. Jackson) 10.10w Ricky Mays, Big Eight Championships 1988 8:34.4h Bill Lundberg, NCAA Championships 1976 NCAA Championships 1976 10.24 Adrian Jones, USC Invitational 1980 8:38.01 Andy Tate, Mt. Sac Relays 2001 39.59 (C. Wiley, A. Coleman, K. Newell, D. Blutcher) 10.25 Pierre Lisk, Big Eight Championships 1995 8:41.2h George Mason, NCAA Championships 1976 NCAA Championships 1977 10.34 Larry Jackson, Big Eight Championships 1976 8:43.12 Steve Heffernan, Florida State Invitational 1990 40.33 (Cooksey, Coleman, Hill, Lisk) 10.34 Charlie Tidwell, Houston Invitational 1969 Kansas Relays 1995 High Jump 200 Meters 7-04.5 Tyke Peacock, Kansas Relays 1982 1,600-Meter Relay 20.27 Larry Jackson, Big Eight Championships 1976 7-04 Keith Guinn, Pan-Am Trials 1975 3:03.96 (S. Whitaker, M. Ricks, L. Mickens, D. Hogan) 20.37 Leo Bookman, Big 12 Championships 2003 7-03.25 Nick Johannsen, Kansas Relays 1994 NCAA Championships 1980 20.3h Laverne Smith, Big Eight Championships 1976 7-03 Barry Schur, Big Eight Championships 1972 3:04.89 (Clemons, Hester, Stigler, McCuin) 20.3h Clifford Wiley, USTFF 1976 7-02 Three Times Big 12 Championships 2012 3:04.93 (Johnson, Clemons, Hester, Stigler) 400 Meters 45.10 Kyle Clemons, Big 12 Championships 2013 Pole Vault NCAA West Preliminary 2013 3:05.88 (J. -

Nebraska Track & Field

NEBRASKA TRACK & FIELD 3 NCAA TEAM TITLES | 106 CONFERENCE TEAM TITLES TWITTER FACEBOOK 78 NCAA CHAMPIONS | 628 ALL-AMERICANS | 911 CONFERENCE CHAMPIONS @NUTRACKANDFIELD NEBRASKATRACKANDFIELD SID: NATE POHLEN | OFFICE: (402) 472-7781 | EMAIL: [email protected] FRANK SEVIGNE HUSKER INVITATIONAL HUSKERS HOST 41ST ANNUAL FRANK Feb. 5-6, 2016 | Bob Devaney Sports Center, Lincoln, Neb. Live Results: Huskers.com TV: Big Ten Network (Tape Delayed - Feb. 13, Noon) SEVIGNE HUSKER INVITATIONAL The Nebraska track and field team hosts the 41st annual Frank Sevigne PARTICIPATING TEAMS Husker Invitational on Friday and Saturday at the Bob Devaney Sports Nebraska, Arizona State, Arkansas State, Auburn, Drake, Illinois (men), Kansas, Center. The meet begins on Friday at Noon and on Saturday at 9:30 a.m. Kansas State, Missouri, Missouri State, Northern Iowa, Omaha (women), South Dakota State, Texas, Texas Tech, UCLA, Chadron State, Colorado School of Mines, with the combined events. The rest of the track and field action begins on Emporia State, Fort Hays State, Nebraska-Kearney, Pittsburg State, Wayne State Friday at 4:30 p.m., and Saturday at Noon. College, Nebraska Wesleyan, St. Olaf, Barton County CC, Garden City CC, Cloud County CC, Iowa Central CC, Iowa Western CC, Southwestern CC, Briar Cliff, More than 30 schools are expected to compete at this year’s meet. On the Concordia University, Dakota State, Oklahoma Baptist men’s side, some of the top teams joining the 15th-ranked Huskers are No. 3 Texas, No. 14 Texas Tech and No. 24 Kansas State. On the women’s side, MEET SCHEDULE (All times Central) No.