The Legacy of John Copley Winslow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anonymous Groups

The Enduring Legacy: the anonymous groups The apology that launched a million amends By Jay Stinnett, Los Angeles July 27th, 2008, marked the 100th anniversary of Frank Buchman’s Spiritual Awakening – one that directly linked him to the cofounders of AA. As a young man Buchman gave everything he had to establishing a shelter for homeless boys in the slums of Philadelphia. The shelters success surpassed his budget and the six-member board of directors insisted that he cut the amount of food being given to his charges. He quit instead of cutting back. Resentment consumed him. His family despaired that he might not come to his senses. His work was destroyed by what he saw as the short-sightedness of others. His health was well past the breaking point. “Everywhere I went, I took me with me,” he later said. During a trip to recuperate in Europe, he exhausted the funds his father gave him and existed on the kindness of his family and the generosity of acquaintances. Tired and dejected he went to an Evangelical Conference in Keswick, England, hoping to connect with F.B. Meyer, a famous minister he knew, for spiritual help. Meyer was not in attendance; another plan gone awry. July 27, 1908, thirty year-old Frank Buchman, a Pennsylvanian Lutheran Minister, walked into an afternoon service with 17 other people to hear Jessie Penn Lewis preach on the cross of Christ. And then it happened. As Buchman sat in that Chapel, “There was a moment of spiritual peak of what God could do for me. -

View of the Essentials of Group Cohesion

ABSTRACT THE SPIRITUAL DYNAMIC IN ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AND THE FACTORS PRECIPITATING A.A.’S SEPARATION FROM THE OXFORD GROUP by Andrew D. Feldheim Alcoholics Anonymous has grown since the mid-1930’s from a loose cohesion of individuals seeking recovery to iconic status as a paradigmatic self-help organization. Few people among the many familiar with A.A. are aware of its genesis from a popular Christian evangelical organization called the Oxford Group. This paper charts the course of A.A. from its Oxford Group roots, both in terms of historical development and the evolution of the spiritual dynamic that served as the functional nexus for both organizations. This paper also addresses key differences in the agendas of both groups that eventually necessitated their separation, as well as the questionable assumption that Alcoholics Anonymous is the more “secular” of the two. THE SPIRITUAL DYNAMIC IN ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS AND THE FACTORS PRECIPITATING A.A.’S SEPARATION FROM THE OXFORD GROUP A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Comparative Religion By Andrew Feldheim Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2013 Advisor ________________ Elizabeth Wilson Reader _________________ Peter Williams Reader ___________________ SCott Kenworthy TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 1: History of the Oxford Group………………………………………………………3 Chapter 2: The Development of Alcoholics Anonymous……………………………...13 Chapter 3: The Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions……………………………………32 Chapter 4: Response to an Anticipated Objection and Closing Remarks……..45 ii Introduction Most people have heard of Alcoholics Anonymous, as well as many of the “spin offs” from this group, like Narcotics Anonymous and Overeaters Anonymous. -

Dr. Frank Buchman Founder of the Oxford Group Dr

Dr. Frank Buchman Founder of the Oxford Group Dr. Frank Buchman & Conrad Adenauer First page “What Is The Oxford Group” description Assorted Oxford Group books. Oxford Group Book 2 Oxford Group Books: A.J. Russell For Sinners Only and V.C. Kitchen I Was A Pagan Rowland H. (left), wife and son. Rowland carried the Oxford Group message to Ebby. Cebra Graves Ebby was released from court to Rowland H. and Cebra’s care Dr. Carl Jung Carl Jung’s Modern Man in Search of a Soul William James Father of American Psychiatry William James Book Varieties of Religious Experience Ebby carried this book to Bill at Townes Hospital The Common Sense of Drinking by Richard Peabody Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic Half measures availed us nothing 1932 Akron newspaper article on the Oxford Group. Frank Buchman is in the picture. Frank Buchman and 60 members of the Oxford Group invited to Akron by Harvey Firestone Reverend Sam Shoemaker With the Calvary Church, and head of the Oxford Group in U.S. Calvary Episcopal Church – 21st Street and Park Avenue South. Headquarters of the Oxford Group. Bill W. went to Oxford meetings before the founding of A.A. Calvary House adjacent to the Calvary Episcopal Church Entrance to the street mission Bill and Ebby Ebby carried “The Message” to Bill Bill and Lois’s house, 182 Clinton Street, Brooklyn A note from Bill to Ebby “Wishes for a Merry Christmas and thanks.” Dr. Leonard Strong – A.A. trustee and brother-in-law of Bill Wilson. Townes Hospital located at Central Park West and 89th Street NYC. -

What's What in Aa History

PLACES & THINGS IN AA HISTORY (Many heartfelt thanks go out to Archie M., who compiled this!!!) REFERENCES: (A) ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS COMES OF AGE (AA) (B) BILL W. by Robert Thomsen (C) CHILDREN OF THE HEALER by Bob Smith & Sue Smith Windows as told to P. Christine Brewer (D) DR. BOB AND THE GOOD OLD TIMERS (AA) (E) A.A. EVERYWHERE ANYWHERE (AA) (G) GRATEFUL TO HAVE BEEN THERE by Nell Wing (H) THE LANGUAGE OF THE HEART (AA) (L) LOIS REMEMBERS by Lois Wilson (N) NOT-GOD by Ernest Kurtz (P) PASS IT ON (AA) (S) SISTER IGNATIA BY Mary C. Darrah (SM) THE SERVICE MANUAL (AA) (TC) TWELVE CONCEPTS FOR WORLD SERVICE (AA) (W) A.A., THE WAY IT BEGAN by Bill Pittman (Note: Each snippet is referenced: example (B 147)=Bill W. page 147, (N 283)=Not-God page 283,(P 111)=Pass It On page 111.) 1st psychiatrists recognize A.A.'s effectiveness Dr. Harry Tiebout (A 2) (E 19) (G 66) (H 369) 1st Trustees Frank Amos (G 92) 1st 3 Steps culled Bill's reading James, teaching Dr. Sam Shoemaker & Oxford Group; 1st Step dealt calamity & disaster, 2nd admission defeat 1 could not live strength own resources, 3rd appeal Higher Power help (P 199) 1st 13th step Lil involved 13th step Victor former Akron mayor (D 97) 1st A.A. archivist Nell Wing (E 78) 1st A.A. Cleveland group meeting May 12, 1939 home Abby G. Cleveland Heights Cleveland, 16 members (A 21) (N 78) (S 32) 1st A.A. clubhouse 334 1/2 24th Street, 1940, old Illustrators Club (A viii,12,180) (B 304) (G 86) (H 47,147) (L 127,172) 1st A.A. -

The First Roman Catholics in Alcoholics Anonymous

CHESNUT — FATHER ED DOWLING — PAGE 1 September 3, 2011 The First Roman Catholics in Alcoholics Anonymous Glenn F. Chesnut Alcoholics Anonymous was founded in 1935 by two men, Bill Wilson and Dr. Bob Smith, who had been brought up as Protestants, and specifically, as New England Congregationalists. In spite of the fact that Congregationalism’s roots had lain in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Puritanism (the world of Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter) this was a denomination which had developed and changed to the point where they very strongly took the liberal side—not the fundamentalist side—in the great fundamentalist-liberal debate which arose within early twentieth-century American Protestantism. In 1957 (two years after AA’s “coming of age” at its St. Louis convention) the Congregationalists united with another modernist mainline American denomination to form the extremely liberal United Church of Christ. At the time they first met, in 1935, Bill W. and Dr. Bob had both recently become involved with a controversial Protestant evangelical association called the Oxford Group, and initially worked with alcoholics under its umbrella. Nevertheless, both of them (as well as the majority of the alcoholics whom they sobered up during the first few years) came from liberal Protestant backgrounds, so a kind of generalized liberal Protestant influence rapidly became just as important as that of the Oxford Group. And contact with the New Thought movement (especially Emmet Fox) introduced an even more radical form of liberal Protestantism which was also a force in early AA. -

WAB: the Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records, 1931-1961 2

The Burke Library Archives, Columbia University Libraries, Union Theological Seminary, New York William Adams Brown Ecumenical Archives Group Finding Aid for The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records, 1931-1961 “You Can Defend America” Songbook WAB: OGMRA Records, Box 4, Folder 3, The Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University in the City of New York. Finding Aid prepared by: Sarah Davis and Brigette C. Kamsler, March 2014 With financial support from the Henry Luce Foundation Summary Information Creator: The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament/Frank Buchman (1878-1961) Title: The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records Inclusive dates: 1931-1961 Bulk dates: 1944-1959 Abstract: The Oxford Group was the parent company of Moral Re-Armament (MRA), an organization/movement that sought to defend America and the nation’s freedoms through a resurgence of morality. Collection contains pamphlets, newspaper articles, advertisements, and other materials related to spreading the MRA message. Size: 4 boxes, 1.75 linear feet Storage: Onsite storage Repository: The Burke Library Union Theological Seminary 3041 Broadway New York, NY 10027 Email: [email protected] WAB: The Oxford Group/Moral Re-Armament Records, 1931-1961 2 Administrative Information Provenance: The papers are part of the William Adams Brown Ecumenical Library Collection, which was founded in 1945 by the Union Theological Seminary Board of Directors. Access: Archival papers are available to registered readers for consultation by appointment only. Please contact archives staff by email to [email protected], or by postal mail to The Burke Library address on page 1, as far in advance as possible Burke Library staff is available for inquiries or to request a consultation on archival or special collections research. -

Sobriety Variety Pages

Sobriety Variety Pages VOLUME 7, ISSUE 10 OCTOBER 2007 long form of tradition 10 No A.A. group or member should ever, in such a way as to implicate A.A., ex- press any opinion on outside controversial issues-particularly those of politics, alcohol reform, or sectarian religion. The Alcoholics Anonymous groups op- pose no one. Concerning such matters they can express no views whatever. step 10 Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it. service concept 10 Every service responsibility should be matched by an equal service authority — the scope of such authority to be always well defined whether by tradition, by resolution, by specific job description or by appropriate charters and bylaws. P A G E 2 letter from the editor This month’s issue focuses on the 10th step, tradittraditionion and service concept. We hope you enjoy the information and activities each month. We also hope you will pass your copy on to an alcoholic who has not read Sobriety Variety Pages and send us your thoughts and ideas at [email protected]. If you or a friend would like to receive a PDF version by email each month just drop us a line at our email address. As always, thanks to the volunteers that “carry thethe message” by answering the intergroup phones and working in a myriad of ways to keep our groups and service structure on the move. Yours in Service, the beginning of Alcoholics Anonymous American understanding of alcoholism in the 1930s “… the only Public opinion in post-Prohibition 1930s America saw alcoholism as a moral failing, and possibility for a the medical profession saw it as a condition that in many cases was incurable and lethal. -

The Serenity Prayer. . .It's Origin Is Traced

HIGHER GROUND The Serenity Prayer. .it's origin is traced. Grapevine, Jan. 1950 AT long last the mystery of the Serenity Prayer has been solved! We have learned who wrote it, when it was written and how it came to the attention of the early members of AA. We have learned, too, how it was originally written, a bit of information which should lay to rest all arguments as to which is the correct quotation. The timeless little prayer has been credited to almost every theologian, philosopher and saint known to man. The most popular opinion on its authorship favors St. Francis of Assisi. It was actually written by Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr, of the Union Theological Seminary, New York City, in about 1932 as the ending to a longer prayer. In 1934 the doctor's friend and neighbor, Dr. Howard Robbins asked permission to use that part of the longer prayer in a compilation he was making at the time. It was published in that year in Dr. Robbins' book of prayers. Dr. Niebuhr says, "Of course, it may have been spooking around for years, even centuries, but I don't think so. I honestly do believe that I wrote it myself." It came to the attention of an early member of AA in 1939. He read it in an obituary appearing in the New York Times. He liked it so much he brought it in to the little office on Vesey St. for Bill W. to read. When Bill and the staff read the little prayer, they felt that it particularly suited the needs of AA. -

Ebby in Exile a Vital AA Link

Ebby in Exile A Vital AA Link By Bob S. Edwin Throckmorton Thacher (1896-1966) This is a second edition, published in 2016 ~~ Bob S. One of Ebby’s favorite drinks But, lucky for us, he gave his was Ballantine’s Ale. last ones to his neighbor. Ebby’s Influential Family Edwin Throckmorton Thacher “Ebby” was born on April 29, 1896, into a family that amassed a great fortune as a railroad wheel manufacturer. The Thacher ancestry was predominant long before Ebby’s father, George H. Thacher II, was born in 1851. Thomas Thacher, his distant grandfather, came to America, from England, during the mid-sixteen hundreds to become the first pastor of the Old South Church, in Boston. The later dynasty achieved prominence in politics, including three George H. Thacher II family members who became mayors of Albany, New York: Ebby’s older brother was John Boyd Thacher II. Mayor of Albany, New York, from 1927— 1940. Ebby’s uncle was John Boyd Thacher. Mayor of Albany, NY, from 1886—1888; then for two full years, 1896 through 1897. Ebby’s Grandfather was George Hornell Thacher (1818—1887). Mayor of Albany, New York, from 1860—1862; then from 1866—1868; and again 1870—1874. A State Park near the suburbs of Albany in Voorheesville, New York, is named after Ebby’s great uncle: John Boyd Thacher State Park. Ebby’s father also was a political figure and hobnobbed with the likes of Abraham Lincoln’s son, Robert Todd Lincoln, and US President, William Howard Taft. As a youth, George was a skillful boxer, ballplayer, oarsman and swimmer. -

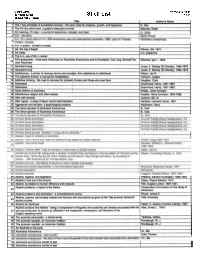

Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 the 7 Key Principles of Successful Recovery: the Basic Tools for Progress, Growth, and Happiness B., Mel

Griffith Library 07/25/0514:13:40 38 Village Street Shelf List 1/18 East Dorset VT 05253 Title Author's Name 1 The 7 key principles of successful recovery: the basic tools for progress, growth, and happiness B., Mel. 2 The 24 hour drink b~u!de to executive survival. Maloney, Ralph. --- 61 A.A. in prison: inmate to inmate. 71 AA, the way it began I Pittman, Bill, 1947-_1 way of life; a reader 10I AA's godparents: three early influences on Alcoholics Anonymous and its foundation, Carl Jung, Emmet Fox, Sikorsky, Igor I., 1929- I Jack Alexander 11 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973:l 12 Abundant living Jones, E. Stanley (Eli Stanley), 1884-1973. I 13 Addictionary: a primer of recovery terms and concepts, from abstinence to withdrawal Wilson, Jan R. I 14 The addictive drinker; a manual for rehabilitation. Thimann, Joseph. I 15 Addictive drinking: the road to recovery for problem drinkers and those who love them Vaughan, Clark. I 16 Addresses Drummond, Henry, 1851-1897. 171 Addresses I Drum~o_nd._Henry. 1851-~~97. 181 Adult children of alcohoTi-cs ~ Woititz, Janet Geringer. 191 Adventurous religion and other essays Fosdick, Harry Emerson, 1878-1969. 20 Afire with serenity Jackson, Bill, Dr. 21 After repeal: a study of liquor control administration Harrison, Leonard Vance, 1891- 22 Aggression and altruism, a psychological analysis. Kaufmann, Harry. 23 The Akron genesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B., Dick. 24 The Akron qenesis of Alcoholics Anonymous B. Dick. Alcohol, hygiene, and legislation EdwardHu~ington!~~ 411 Alcohol in and out of the church lOates,_~ayne Edward, 1917- ~IXcohof; Its relation to human efficiency and longevity Fisk, Eugene Lyman, 1867-1931.~ Alcohol problems; a report to the Nation. -

Does the Oxford Group Still Exist? Fr. Bill W

Does the Oxford Group Still Exist? Fr. Bill W. This past summer I took a trip back in time. Physically, the trip took my wife and me to Switzerland – to a grand, hundred year old hotel known as Mountain House and perched high atop the steep cliffs overlooking Lake Geneva. But spiritually speaking, you might say we traveled farther still. The trip took us to that “4th dimension of existence” that the Big Book invites each one of us to come and explore. We attended an Initiatives of Change Conference aptly entitled: “Tools for Change.” The eight-day conference attracted over 350 men and women from more than fifty nations. People came from South Africa and from Australia – from India and from Egypt. There were Hindus and Christians, Muslims and Buddhists while many claimed membership in no formal religion at all. Each came to share and to sharpen the very same tools that had launched the fellowship of Alcoholics Anonymous back in the late 1930’s; and yet, as far as I know, I was the only recovering alcoholic in attendance. Prior to calling themselves Initiatives of Change, the group was known as: Moral Re-Armament, and before that they were: The Oxford Group, and before that they were: A First Century Christian Fellowship. From their very beginnings they had tried to live life as Jesus had lived his i.e. simply, and lovingly, and marked by a radical form of forgiveness. They strived for the same virtues he had demon- strated 2,000 years ago: Absolute Honesty, Purity, Unselfishness, and Love and they talked candidly of the many times they fell short. -

The Four Absolutes of the Oxford Group Do They Have a Place in Today’S 12 Step Programs? by Fr

The Four Absolutes of the Oxford Group Do they have a place in today’s 12 Step Programs? By Fr. Bill W. Step 6: “Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.” Step 7: “Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.” A wise observer noted: “It’s always the victor in any war that gets to write the history.” This certainly proved to be the case when the Big Book of Alcoholics Anonymous was written. Troublesome parts of the A. A. story were quietly omitted, not so much with an intent to deceive, but more as a way to protect the young Fellowship from being tainted by the negative publicity then surrounding the man responsible for developing so many of its core beliefs and principles: Dr. Frank Buchman. Buchman was the Lutheran minister who founded an evangelical Christian movement focused on producing deep and radical change in individuals – and, subsequently, in communities and nations. Known initially as a First Century Christian Fellowship and later as the Oxford Group, Buchman provided many of the spiritual tools that helped Bill Wilson, Dr. Bob and many A.A. Pioneers find sobriety. While several reasons contributed to the alcoholics in the Oxford Group separating themselves from Buchman in the late 1930’s and forming into their own Fellowship, a primary factor for their departure was that Buchman had come under fire for making statements that were interpreted in the press to be “pro Adolph Hitler.”(1) The adverse publicity this generated plagued the Group for many years to come. Naturally, when the alcoholics left and started their own society, they wanted to downplay anything in their past that might associate their new Fellowship with Buchman.