Delimitation of Information Between Grammatical Rules and Lexicon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conditionals in Political Texts

JOSIP JURAJ STROSSMAYER UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES Adnan Bujak Conditionals in political texts A corpus-based study Doctoral dissertation Advisor: Dr. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2014 CONTENTS Abstract ...........................................................................................................................3 List of tables ....................................................................................................................4 List of figures ..................................................................................................................5 List of charts....................................................................................................................6 Abbreviations, Symbols and Font Styles ..........................................................................7 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................9 1.1. The subject matter .........................................................................................9 1.2. Dissertation structure .....................................................................................10 1.3. Rationale .......................................................................................................11 1.4. Research questions ........................................................................................12 2. Theoretical framework .................................................................................................13 -

EVIDENTIALS and RELEVANCE by Ely Ifantidou

EVIDENTIALS AND RELEVANCE by Ely Ifantidou Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London 1994 Department of Phonetics and Linguistics University College London (LONDON ABSTRACT Evidentials are expressions used to indicate the source of evidence and strength of speaker commitment to information conveyed. They include sentence adverbials such as 'obviously', parenthetical constructions such as 'I think', and hearsay expressions such as 'allegedly'. This thesis argues against the speech-act and Gricean accounts of evidentials and defends a Relevance-theoretic account Chapter 1 surveys general linguistic work on evidentials, with particular reference to their semantic and pragmatic status, and raises the following issues: for linguistically encoded evidentials, are they truth-conditional or non-truth-conditional, and do they contribute to explicit or implicit communication? For pragmatically inferred evidentials, is there a pragmatic framework in which they can be adequately accounted for? Chapters 2-4 survey the three main semantic/pragmatic frameworks for the study of evidentials. Chapter 2 argues that speech-act theory fails to give an adequate account of pragmatic inference processes. Chapter 3 argues that while Grice's theory of meaning and communication addresses all the central issues raised in the first chapter, evidentials fall outside Grice's basic categories of meaning and communication. Chapter 4 outlines the assumptions of Relevance Theory that bear on the study of evidentials. I sketch an account of pragmatically inferred evidentials, and introduce three central distinctions: between explicit and implicit communication, truth-conditional and non-truth-conditional meaning, and conceptual and procedural meaning. These distinctions are applied to a variety of linguistically encoded evidentials in chapters 5-7. -

European Journal of Educational Research Volume 9, Issue 1, 395- 411

Research Article doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.9.1.395 European Journal of Educational Research Volume 9, Issue 1, 395- 411. ISSN: 2165-8714 http://www.eu-jer.com/ ‘Sentence Crimes’: Blurring the Boundaries between the Sentence-Level Accuracies and their Meanings Conveyed Yohannes Telaumbanua* Nurmalina Yalmiadi Masrul Politeknik Negeri Padang, Universitas Pahlawan Tuanku Universitas Dharma Andalas Universitas Pahlawan Tuanku INDONESIA Tambusai Pekanbaru Riau Padang, INDONESIA Tambusai, INDONESIA Indonesia, INDONESIA Received: September 9, 2019▪ Revised: October 29, 2019 ▪ Accepted: January 15, 2020 Abstract: The syntactic complexities of English sentence structures induced the Indonesian students’ sentence-level accuracies blurred. Reciprocally, the meanings conveyed are left hanging. The readers are increasingly at sixes and sevens. The Sentence Crimes were, therefore, the major essences of diagnosing the students’ sentence-level inaccuracies in this study. This study aimed at diagnosing the 2nd-year PNP ED students’ SCs as the writers of English Paragraph Writing at the Writing II course. Qualitatively, both observation and documentation were the instruments of collecting the data while the 1984 Miles & Huberman’s Model and the 1973 Corder’s Clinical Elicitation were employed to analyse the data as regards the SCs produced by the students. The findings designated that the major sources of the students’ SCs were the subordinating/dependent clauses (noun, adverb, and relative clauses), that-clauses, participle phrases, infinitive phrases, lonely verb phrases, an afterthought, appositive fragments, fused sentences, and comma splices. As a result, the SCs/fragments flopped to communicate complete thoughts because they were grammatically incorrect; lacked a subject, a verb; the independent clauses ran together without properly using punctuation marks, conjunctions or transitions; and two or more independent clauses were purely joined by commas but failed to consider using conjunctions. -

English Cleft Constructions: Corpus Findings and Theoretical Implications∗

English Cleft Constructions: Corpus Findings and Theoretical Implications∗ March, 2007 Abstract The paper presents a structural analysis of three clefts construc- tions in English. The three constructions all provide unique options for presenting `salient' discourse information in a particular serial or- der. The choice of one rather than another of these three clefts is deter- mined by various formal and pragmatic factors. This paper reports the findings for these three types of English cleft in the ICE-GB (Interna- tional corpus of English-Great Britian) and provides a constraint-based analysis of the constructions. 1 General Properties The examples in (1) represent the canonical types of three clefts, it-cleft, wh-cleft, and inverted wh-cleft in English: (1) a. It-cleft: In fact it's their teaching material that we're using... <S1A-024 #68:1:B> b. Wh-cleft: What we're using is their teaching material. c. Inverted wh-cleft: Their teaching material is what we are using. ∗Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 2005 Society of Modern Gram- mar Conference (Oct 15, 2005) and the 2006 Linguistic Society of Korea and Linguistic Association of Korea Joint Conference (Oct 21, 2006). I thank the participants of the conferences for comments and questions. I also thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and criticisms, which helped me reshape the paper. All remaining errors and misinterpretations are of course mine. 1 As noted by Lambrecht (2001) and others, it has generally been assumed that these three different types of clefts share the identical information- structure properties given in (2):1 (2) a. -

6 Adverbs of Action and Logical Form KIRK LUDWIG

6 Adverbs of Action and Logical Form KIRK LUDWIG Adverbs modify verbs ( ‘ He cut the roast carefully ’ ), adjectives ( ‘ A very tall man sat down in front of me ’ ), other adverbs ( ‘ He cut the roast very carefully ’ ), and sentences ( ‘ Fortunately , he cut the roast with a knife ’ ). This chapter focuses on adverbial modifi ca- tion of verbs, and specifi cally action verbs, that is, verbs that express agency – though many of the lessons extend to sentences with event verbs generally. Adverbs and adver- bial phrases are traditionally classifi ed under the headings of manner ( ‘ carefully ’ ), place ( ‘ in the kitchen ’ ), time ( ‘ at midnight ’ ), frequency ( ‘ often ’ ), and degree ( ‘ very ’ ). The problem of adverbials lies in understanding their systematic contribution to the truth conditions of the sentences in which they appear. The solution sheds light on the logical form of action sentences with and without adverbials. An account of the logical form of a sentence aims to make clear the role of its seman- tically primitive expressions in fi xing the sentence ’ s interpretive truth conditions and, in so doing, to account for all of the entailment relations the sentence stands in toward other sentences in virtue of its logico - semantic form. This is typically done by providing a regimented paraphrase of the sentence that makes clearer the logico - semantic con- tribution of each expression. For example, the logical form of ‘ The red ball is under the bed ’ may be represented as ‘ [The x : x is red and x is a ball][the y : y is a bed]( x is under y ). ’ Thus, the defi nite descriptions are represented as functioning as restricted quanti- fi ers, and the adjective ‘ red ’ is represented as contributing a predicate conjunct to the nominal restriction on the variable in the fi rst defi nite description. -

When Stylistic and Social Effects Fail to Converge: a Variation Study of Complementizer Choice

Laura Staum QP 2, May 2005 When Stylistic and Social Effects Fail to Converge: a variation study of complementizer choice 1. The Question Labov observes in The Social Stratification of English in New York City that “in general, a variant that is used by most New Yorkers in formal styles is also the variant that is used most often in all styles by speakers who are ranked higher on an objective socio- economic scale” (1982, 279). This observation, that stylistic effects tend to mirror social effects, has been considered a guiding principle of variationist sociolinguistics for long enough that when a variable shows evidence of stylistic conditioning, we may expect or even assume that social conditioning is also present. Indeed, there are good theoretical reasons to believe that this relationship is anything but a coincidence; the exploration of this and related ideas has led to a much deeper understanding of the nature of social meaning, among other things. However, this relationship between stylistic and social conditioning is not a logical necessity, but depends crucially on the specific social meanings associated with the variables in question, and if the mirroring relationship does not always hold, then we need to account somehow for the existence of a set of variables that have so far been largely ignored in the literature. Because the positive relationship between social and stylistic stratification has already been demonstrated for several different types of variables, and we have no reason to believe that it does not hold in these cases, the most straightforward way to further investigate this relationship is to look for evidence of new, un- or under-studied variables for which it does not hold. -

DCMS Sub-Committee Inquiry

1 DCMS SUB-COMMITTEE – ONLINE SAFETY AND ONLINE HARMS INQUIRY DCMS Sub-Committee Inquiry Online Safety and Online Harms About 5Rights Foundation 5Rights develops new policy, creates innovative frameworks, develops technical standards, publishes research, challenges received narratives and ensures that children's rights and needs are recognised and prioritised in the digital world. Our focus is on implementable change and our work is cited and used widely around the world. We work with governments, inter-governmental institutions, professional associations, academics, businesses, and children, so that digital products and services can impact positively on the lived experiences of young people. 5Rights Foundation speaks specifically on behalf of and is informed by the views of young people. Therefore, our comments reflect, and are restricted to, the experiences of young people under the age of 18. However, we recognise that many of our views and recommendations are relevant to other user groups and we welcome any efforts that government makes to make the digital world more equitable for all user groups, particularly the vulnerable. 2 Responses to Consultation Questions 1. How has the shifting focus between ‘online harms’ and ‘online safety’ influenced the development of the new regime and draft Bill? The change in language from ‘online harms’ to ‘online safety’ reflects the journey the Bill has taken from its initial conception in 2017 as a green paper to the draft Act published in May 2021. It is a welcome recognition of the limitations of an approach which focuses on responding to harm after it has occurred, and of the need to make online services safe by design. -

Writing Center SMC Campus Center 621 W

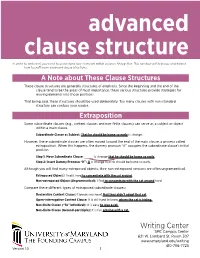

advanced clause structure In order to write well, you need to understand how elements within a clause fit together. This handout will help you understand how to craft more advanced clause structures. A Note about These Clause Structures These clause structures are generally structures of emphasis. Since the beginning and the end of the clause tend to be the areas of most importance, these various structures provide strategies for moving elements into those positions. That being said, these structures should be used deliberately. Too many clauses with non-standard structure can confuse your reader. Extraposition Some subordinate clauses (e.g., content clauses and non-finite clauses) can serve as a subject or object within a main clause. Subordinate Clause as Subject: That he should be home so early is strange. However, these subordinate clauses are often moved toward the end of the main clause, a process called extraposition. When this happens, the dummy pronoun “it” occupies the subordinate clause’s initial position. Step 1: Move Subordinate Clause: _____ is strange that he should be home so early. Step 2: Insert Dummy Pronoun “It”: It is strange that he should be home so early. Although you will find many extraposed objects, their non-extraposed versions are often ungramamtical. Extraposed Object: I find it hard to concentrate with the cat around. Non-extraposed Object (Ungrammatical): I find to concentrate with the cat around hard. Compare these different types of extraposed subordinate clauses: Declarative Content Clause: It breaks my heart that they didn’t adopt that cat. Open-interrogative Content Clause: It is still hard to know where the cat is hiding. -

How Should We Revise the Paratactic Theory?∗

How Should We Revise the Paratactic Theory?∗ KEITH FRANKISH 1. Donald Davidson’s original 1969 statement of the paratactic theory of indirect discourse (PT) involved two claims. First, there was a claim about logical form: LF: The logical form of an indirect speech report of the form ‘A said that p’ is the paratactic pair: A said that. >u where u is an utterance, ‘that’ a demonstrative referring to u (the arrowhead here indicating demonstration), and ‘said’ a two-place relation (henceforth written ‘samesaid’1) between persons and utterances, such that ‘A samesaid u’ is true if and only if A made an utterance with the same import as u. Davidson also added a claim about the surface form of indirect speech: SF: The surface form of an indirect speech report coincides with its logical form. That is to say, the surface form of indirect speech is itself paratactic and requires only the insertion of a period (‘a tiny orthographic change ... without semantic significance’, as Davidson put it) to be made explicit. If SF is true, then the ‘that’ of ‘says that’ is, grammatically speaking, a demonstrative, and the utterance to which it refers is just the reporter’s utterance of the words immediately following it.2 Early objectors to PT tended to attack LF directly, arguing that it did not yield a satisfactory account of the truth conditions of indirect speech reports. Defenders of PT usually found ways of answering, or at least of dodging, these objections and the theory survived and prospered. More recent critics, however, have concentrated their fire upon SF, and this flanking attack may ultimately prove more damaging for PT. -

MORPHOLOGICAL SPLIT ERGATIVE ALIGNMENT and SYNTACTIC NOMINATIVE-ACCUSATIVE ALIGNMENT in PESH Claudine Chamoreau

MORPHOLOGICAL SPLIT ERGATIVE ALIGNMENT AND SYNTACTIC NOMINATIVE-ACCUSATIVE ALIGNMENT IN PESH Claudine Chamoreau To cite this version: Claudine Chamoreau. MORPHOLOGICAL SPLIT ERGATIVE ALIGNMENT AND SYNTACTIC NOMINATIVE-ACCUSATIVE ALIGNMENT IN PESH. International Journal of American Linguis- tics, University of Chicago Press, inPress. halshs-03112558 HAL Id: halshs-03112558 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03112558 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chamoreau, C. forthcoming. Morphological split ergative alignment and syntactic nominative–accusative alignment in Pesh. International Journal of American Linguistics. MORPHOLOGICAL SPLIT ERGATIVE ALIGNMENT AND SYNTACTIC NOMINATIVE–ACCUSATIVE ALIGNMENT IN PESH CLAUDINE CHAMOREAU CNRS (CEMCA/SEDYL) ABSTRACT Pesh (Chibchan, Honduras) has until now been described as having a morphological nominative–accusative alignment. This paper argues that Pesh displays a bi-level split ergative pattern for morphological alignment. On the first level of the system, Pesh features a split alignment that is conditioned by the way the arguments are expressed. It has a nominative– accusative alignment for the obligatory indexing of arguments on the verb, and three systems of alignment for flagging case. The distribution of these three systems shapes the second level where ergative–absolutive, tripartite, and nominative–accusative are seen depending on the types of clause and the varieties spoken. -

Syntactic Positions of the Content Clause in Contemporary Polish

東京外国語大学論集第 92 号(2016) 129 Syntactic Positions of the Content Clause in Contemporary Polish MALEJKA Jagna Introduction 1. Traditional syntax and formal syntax in Poland 2. Connotation and syntactic accommodation 3. Sentence – a definition in the formal syntax framework 4. Content clause 5. Syntactic position 6. Lexemes connoting content clauses 7. Obligatory and optional occupying of a semantic position 8. Types of equivalent phrases List of symbols used Introduction The aim of this paper is to describe a certain type of syntactic units and their syntactic position in a sentence in Polish. Polish is one of the West Slavic languages (the group also includes Czech, Slovak and endangered Sorbian languages) of the Slavic group. It is a fusional (inflected) language with a relatively flexible word order1). The phenomena described in this paper have been analysed by means of tools of formal Structural Syntax, as opposed to the methods of traditional syntax2). First, the distinction between formal syntax and traditional syntax is Polish linguistics is presented, and basic terms are defined which are crucial for this distinction, i.e. connotation, syntactic accommodation, sentence, clause, syntactic position. In this paper there are analysed Polish complex/compound clauses excerpted from contemporary journalistic and literary texts (excluding poetry), dictionaries, and research papers on syntax. Syntactic paradigms used in this paper were taken from two sources: Słownik syntaktyczno-generatywny czasowników polskich and Inny słownik języka polskiego (the only comprehensive dictionary of Polish which contains valency of lexemes). It is also vital to introduce some methodological assumptions on which the analysis was based, and to define precisely the terms used, as differing definitions can be found in many linguistic papers. -

Views 14 (1) 2005

VIENNA ENGLISH WORKING PAPERS VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 JUNE, 2005 INTERNET EDITION AVAILABLE AT HTTP://WWW.UNIVIE.AC.AT/ANGLISTIK/ANG_NEW/ONLINE_PAPERS/VIEWS.HTML CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE EDITORS...................................................................... 1 JULIA HÜTTNER Formulaic language and genre analysis: the case of student academic papers.................................................... 3 GUNTHER KALTENBÖCK Charting the boundaries of syntax: a taxonomy of spoken parenthetical clauses ...................................... 21 ANGELIKA RIEDER Vocabulary learning through reading: influences and teaching implications................................................... 54 IMPRESSUM............................................................................................ 64 LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Dear Readers, After a pronounced diachronic focus in our latest VIEWS issue, this time synchronic issues are back – 'with a vengeance'. They address conceptual questions of delimiting and defining well-known notions such as formulaic sequences and parenthetical clauses as well as the more applied question of vocabulary teaching and learning. Julia Hüttner explores the potential of linking formulaic sequences with genre analysis. This novel approach offers promising inroads into the 2 VIEWS notoriously difficult question of how to pin down and classify formulaic language by linking it to the question of genre-specific functions. Classifying and delimiting an elusive concept is also Gunther Kaltenböck’s agenda, who investigates the class