The Monetary, Regulatory and Competitive Implications of the Restructuring of the Japanese Banking Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Report –Annual Review– Integrated Report 2017 –Annual Review– April 2016 – March 2017 Our Corporate Philosophy

Mizuho Financial Group Mizuho Financial Group | 2017 Integrated Report –Annual Review– Integrated Report 2017 –Annual Review– April 2016 – March 2017 Our Corporate Philosophy Mizuho, the leading Japanese financial services group with a global presence and a broad customer base, is committed to: Providing customers worldwide with the highest quality financial services with honesty and integrity; Anticipating new trends on the world stage; Expanding our knowledge in order to help customers shape their future; Growing together with our customers in a stable and sustainable manner; and Bringing together our group–wide expertise to contribute to the prosperity of economies and societies throughout the world. These fundamental commitments support our primary role in bringing fruitfulness for each customer and the economies and the societies in which we operate. Mizuho creates lasting value. It is what makes us invaluable. Corporate Philosophy: Mizuho’s The Mizuho Values fundamental approach to business Customer First: activities, based on the The most trusted partner lighting raison d’etre of Mizuho the future Innovative Spirit: Vision: Progressive and flexible thinking Mizuho’s vision for Mizuho’s Corporate Identity Mizuho’s the future, realized Team Spirit: through the practice of Diversity and collective strength “Corporate Philosophy” Speed: Acuity and promptness The Mizuho Values: The shared values and principles of Passion: Mizuho’s people, uniting all executives and Communication and challenge for employees together to pursue “Vision” the future 1 Mizuho Financial Group The most trusted financial services group with a global presence and a broad customer base, contributing to the prosperity of the world, Asia, and Japan 2017 Integrated Report 2 Editorial Policy Contents This Integrated Report includes financial information as well as non-financial information on such subjects as ESG. -

To Our Shareholders and Customers Issues We Faceinfiscal2000

To Our Shareholders and Customers — The Dawn of a New Era — Review of Fiscal 1999 For the Japanese financial sector, fiscal 1999 During fiscal 1999, we strengthened our man- marked the start of a totally new era in the his- agement infrastructure and corporate structure tory of finance in Japan. by improving business performance, restructur- In August 1999, The Fuji Bank, Limited, ing operations, strengthening risk management The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Limited, and The and managing consolidated business activities Industrial Bank of Japan, Limited, reached full under a stronger group strategy. agreement to consolidate their operations into a comprehensive financial services group to be • Improving Business Performance called the Mizuho Financial Group. In the fol- We have identified the domestic corporate and lowing six months after the announcement, retail markets as our priority business areas. several other major Japanese financial institu- Our goals in these markets are to enhance our tions announced mergers and consolidations of products and services to meet the wide-ranging one form or another. needs of our customers, and to improve cus- At the same time, conditions in the financial tomer convenience by using information tech- sector changed dramatically as foreign-owned nology to diversify our service channels. financial institutions began in earnest to With respect to enhancing products and expand their presence in Japan, companies services, we focused on services provided to from other sectors started to move into the members of the Fuji First Club, a membership To Our Shareholders and Customers To financial business, and a number of Internet- reward program that offers special benefits to based strategic alliances were formed across dif- member customers, and on our product lineup ferent sectors and industries. -

The Corporate Culture in a Japanese Bank: Study of the Changing Organizational World

The Corporate Culture in a Japanese Bank: Study of the Changing Organizational World by HIROFUMI HOJO B.A. Law, Keio University (1986) SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2005 © Hirofumi Hojo 2005. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. ^ /' Ar Signature of Author: 'I (! J MIT SloVn School of Management May 6, 2005 Certified by: I John E. Van Maanen Erwin H. Schell Professor of Organization Studies Thesis Advisor Accepted by: / I I , / Stephen J. Sacca Director, Sloan Fellows Program in Innovation and Global Leadership lMASSACHUSETSINSTITE OF TECHNOLOGY 'A I IX~IFtes SEP 012005 LIBRARIES 2 The Corporate Culture in a Japanese Bank: Study of the Changing Organizational World by HIROFUMI HOJO Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management on May 6, 2005 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management ABSTRACT The environment surrounding companies is constantly changing. and that change forces companies into paradigm shifts. If a company cannot cope with change, it faces the distinct possibility of being be weeded out of the industry. Today, Japanese companies are facing dramatic environmental change. For example, the introduction of new global accounting rules is changing the behavior of equity holders. The long and deep recession following the collapse of the Japanese "bubble" economy continues to sap the economic energy of many Japanese companies, and most leaders of those companies still struggle to find new ways to exit from this dark tunnel. -

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fuji Bank Group

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Fuji Bank Group Balance Sheet Thousands of Thousands of Millions of yen U.S. dollars Millions of yen U.S. dollars March 31, 1998 1997 1998 March 31, 1998 1997 1998 ASSETS LIABILITIES AND STOCKHOLDERS’ EQUITY Liabilities Cash and Due from Banks................................................................. ¥ 00,000,0002,821,634 ¥00,000,0004,341,701 $000,000,00021,359,834 Deposits (Note 8) .............................................................................. ¥ 00,000,00034,552,361 ¥00,000,00038,649,481 $000,000,000261,562,164 Call Money and Bills Sold ................................................................. 3,755,273 4,310,517 28,427,509 Call Loans and Bills Purchased .......................................................... 1,453,230 2,230,223 11,000,989 Trading Liabilities .............................................................................. 2,057,167 — 15,572,803 Borrowed Money (Note 9)................................................................ 2,947,169 2,252,185 22,310,138 Commercial Paper and Other Debt Purchased................................... 43,216 188,430 327,152 Foreign Exchange.............................................................................. 113,221 82,000 857,087 Trading Assets (Note 3) ..................................................................... 3,265,412 — 24,719,248 Bonds and Notes (Note 10) ............................................................... 1,657,224 1,322,494 12,545,228 Convertible Bonds (Note 11) ........................................................... -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Nber Working Paper Series Did Mergers Help Japanese

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DID MERGERS HELP JAPANESE MEGA-BANKS AVOID FAILURE? ANALYSIS OF THE DISTANCE TO DEFAULT OF BANKS Kimie Harada Takatoshi Ito Working Paper 14518 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14518 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2008 The paper started as a joint project with Dr. Kelly Wang when she was Assistant Professor at University of Tokyo. The authors are grateful to her for her help in providing us with computer programs and in discussion the ways to apply her methods to the Japanese banking data. Upon Dr. Wang's departure from the University of Tokyo, the project was carried on by the current two authors with full consent from Dr. Wang. The current two authors take responsibility for any remaining errors. Mr. Shuhei Takahashi provided us with superb research assistance. We are grateful for financial support from Nomura foundation for social science and Chuo University for Special Research. We are also grateful for helpful discussions with Masaya Sakuragawa, Naohiko Baba, Satoshi Koibuchi, Woo Joong Kim, Joe Peek, Kazuo Kato and for insigutful comments from participants in Asia pacific Economic Association in Hong Kong in 2007, Japan Economic Association in 2008, NBER Japan Group Meeting in 2008 and Asian FA-NFA 2008 International Conference. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. -

Corporate Matching Gifts

Corporate Matching Gifts Your employer may match your contribution. The Corporations listed below have made charitable contributions, through their Matching Gift Programs, for educational, humanitarian and charitable endeavors in years past. Some Corporations require that you select a particular ministry to support. A K A. E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Kansas Gty Southern Industries Inc Abbott Laboratories Kemper Insurance Cos. Adams Harkness & Hill Inc. Kemper National Co. ADC Telecommunications Kennametal Inc. ADP Foundation KeyCorp Adobe Systems, Inc. Keystone Associates Inc. Aetna Inc. Kimberly Clark Foundation AG Communications Systems Kmart Corp. Aid Association for Lutherans KN Energy Inc. Aileen S. Andrew Foundation Air Products and Chemicals Inc. L Albemarle Corp. Lam Research Corp. Alco Standard Fdn Lamson & Sessions Co. Alexander & Baldwin Inc. LandAmerica Financial Group Inc. Alexander Haas Martin & Partners Leo Burnett Co. Inc. Allegiance Corp. and Baxter International Levi Strauss & Co. Allegro MicroSystems W.G. Inc. LEXIS-NEXIS Allendale Mutual Insurance Co. Lexmark Internaional Inc. Alliance Capital Management, LP Thomas J. Lipton Co. Alliant Techsystems Liz Claiborne Inc. AlliedSignal Inc. Loews Corp. American Express Co. Lorillard Tobacco Co. American General Corp. Lotus Development Corp. American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Lubrizol Corp. American Inter Group Lucent Technologies American International Group Inc. American National Bank & Trust Co. of Chicago M American Stock Exchange Maclean-Fogg Co. Ameritech Corp. Maguire Oil Co. Amgen In c. Mallinckrodt Group Inc. AmSouth BanCorp. Foundation Management Compensation AMSTED Industries Inc. Group/Dulworth Inc. Analog Devices Inc. Maritz Inc. Anchor/Russell Capital Advisors Inc. Massachusetts Mutual Life Andersons Inc. Massachusetts Financial Services Investment Aon Corp. Management Archer Daniels Midland Massachusetts Port Authority ARCO MassMutual-Blue Chip Co. -

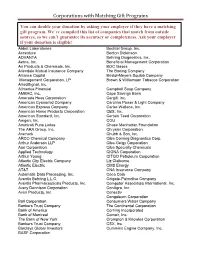

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs You can double your donation by asking your employer if they have a matching gift program. We’ve compiled this list of companies that match from outside sources, so we can’t guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Ask your employer if your donation is eligible! Abbot Laboratories Bechtel Group, Inc. Accenture Becton Dickinson ADVANTA Behring Diagnostics, Inc. Aetna, Inc. Beneficial Management Corporation Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. BOC Gases Allendale Mutual Insurance Company The Boeing Company Alliance Capital Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company Management Corporation, LP Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation AlliedSignal, Inc. Allmerica Financial Campbell Soup Company AMBAC, Inc. Cape Savings Bank Amerada Hess Corporation Cargill, Inc. American Cyanamid Company Carolina Power & Light Company American Express Company Carter-Wallace, Inc. American Home Products Corporation CBS, Inc. American Standard, Inc. Certain Teed Corporation Amgen, Inc. CGU Ammirati Puris Lintas Chase Manhattan Foundation The ARA Group, Inc. Chrysler Corporation Aramark Chubb & Son, Inc. ARCO Chemical Company Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp. Arthur Anderson LLP Ciba-Geigy Corporation Aon Corporation Ciba Specialty Chemicals Applied Technology CIGNA Corporation Arthur Young CITGO Petroleum Corporation Atlantic City Electric Company Liz Claiborne Atlantic Electric CMS Energy AT&T CNA Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Coca Cola Aventis Behring L.L.C. Colgate-Palmolive Company Aventis Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc. Computer Associates International, Inc. Avery Dennison Corporation ConAgra, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. Conectiv Congoleum Corporation Ball Corporation Consumers Water Company Bankers Trust Company The Continental Corporation Bank of America Corning Incorporated Bank of Montreal Comair, Inc. The Bank of New York Crompton & Knowles Corporation Bankers Trust Company CSX, Inc. -

Annual Report 2017 for the Year Ended March 31, 2017 from a Company Making Things, to a Company Making People Smile

Annual Report 2017 For the year ended March 31, 2017 From a company making things, to a company making people smile. Just a glance at our vehicles and you can imagine days filled with excitement. Just a glimpse of jet wings above and you can envision worlds yet unseen. But no matter the time or place, we are always by our customers’ sides. What is important is not how many cars we make, but how many smiles we can create. More than a century has passed since the founding of Aircraft Research Laboratory, the forerunner of SUBARU. Now, Fuji Heavy Industries Ltd. has been reborn as SUBARU CORPORATION. From making things to delivering value that shines in people’s hearts, SUBARU aims to touch the hearts of people and bring smiles to their faces. We constantly challenge ourselves to ensure that satisfaction with SUBARU is reflected in the happy faces of our customers. SUBARU CORPORATION 01 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 SUBARU CORPORATION 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Vision for 2020 Not big in size, but a high-quality company with distinctive strengths For SUBARU, by no means a large automaker, the two strategies of uncompromising differentiation and added-value are essential for achieving sustained growth in a fierce competitive environment. We will narrow our focus to categories and markets in which we can leverage our strengths, practice selection and concentration in allocation of limited management resources, and further accelerate two initiatives: enhancing the SUBARU brand and building a strong business structure. And, we will seek to have a prominent presence in customers’ minds. -

Foreign Penetration of Japan's Investment-Banking

Foreign Penetration of Japan’s Investment-Banking Market: Will Japan Experience the “Wimbledon Effect”? Nicole Pohl July 2002 1 The Asia/Pacific Research Center (A/PARC) is an important Stanford venue where faculty and students, visiting scholars, and distinguished business and government leaders meet and exchange views on contemporary Asia and U.S. involvement in the region. A/PARC research results in seminars and conferences, published studies, occasional and discussion papers, special reports, and books. A/PARC maintains an active industrial affiliates and training program, involving more than twenty-five U.S. and Asian companies and public agencies. Members of A/PARC’s faculty have held high-level posts in government and business. Their interdisciplinary expertise generates research of lasting significance on economic, political, technological, strategic, and social issues. Asia/Pacific Research Center Encina Hall, Room E301 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94306-6055 http://APARC.stanford.edu 2 About the Author Nicole Pohl was a visiting scholar at the Asia/Pacific Research Center in 2001–2002. An assistant professor of economics at Franklin & Marshall College, she received her doctorate in economics from Gerhard Mercator University Duisburg in 2000. Her major research field is the economic geography of the financial sector. 3 4 Contents 1 Background 9 2 The Environment for Foreign Financial Institutions in Japan 13 2.1 Relationship Banking As a Barrier to Entry for Foreign Banks 13 2.2 The Role of Bureaucracy 14 3 Market-Entry Strategies -

ISSN 1045-6333 the FABLE of the KEIRETSU Yoshiro Miwa J. Mark Ramseyer Discussion Paper No. 316 3/2001 Harvard Law School Cambri

ISSN 1045-6333 THE FABLE OF THE KEIRETSU Yoshiro Miwa J. Mark Ramseyer Discussion Paper No. 316 3/2001 Harvard Law School Cambridge, MA 02138 The Center for Law, Economics, and Business is supported by a grant from the John M. Olin Foundation. This paper can be downloaded without charge from: The Harvard John M. Olin Discussion Paper Series: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/ JEL: G3, K2, L1, P5 Address correspondence to: University of Tokyo Faculty of Economics 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo FAX: 03-5841-5521 [email protected] [email protected] The Fable of the Keiretsu by Yoshiro Miwa & J. Mark Ramseyer* Abstract: Central to so many accounts of post-war Japan, the keiretsu corporate groups have never had economic substance. Conceived by Marxists committed to locating "domination" by "monopoly capital," they found an early audience among western scholars searching for evidence of culture-specific group behavior in Japan. By the 1990s, they had moved into mainstream economic studies, and keiretsu dummies appeared in virtually all econometric regressions of Japanese industrial or corporate structure. Yet the keiretsu began as a figment of the academic imagination, and they remain that today. The most commonly used keiretsu roster first groups large financial institutions by their pre-war antecedents. It then assigns firms to a group if the sum of its loans from those institutions exceeds the amount it borrows from the next largest lender. Other rosters start by asking whether firm presidents meet occasionally with other presidents for lunch. Regardless of the definition used, cross-shareholdings were trivial even during the years when keiretsu ties were supposedly strongest, and membership has only badly proxied for "main bank" ties. -

The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank,Limited the Fuji Bank,Limited the Industrial Bank of Japan,Limited

QX/MZHO Interim 2000入稿原稿 01.1.23 7:26 PM ページ c1 (W) 570pt x (H) 648pt 2000 INTERIM REPORT The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank,Limited The Fuji Bank,Limited The Industrial Bank of Japan,Limited c1 QX/MZHO Interim 2000入稿原稿 01.1.23 7:26 PM ページ c2 (W) 570pt x (H) 648pt To Our Shareholders and Customers Mizuho Holdings Established We are pleased to issue our first financial report as the newly formed bank holding company for three of Japan’s leading financial institutions—The Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank, Limited (“DKB”), The Fuji Bank, Limited (“Fuji Bank”), and The Industrial Bank of Japan, Limited (“IBJ”). Mizuho Holdings, Inc. (“MHHD”), was established through a stock-for-stock exchange on September 29, 2000, thus marking the formal inauguration of the Mizuho Financial Group (“MHFG”). Following this, on October 1, 2000, Mizuho Securities Co., Ltd. (“Mizuho Securities”), and Mizuho Trust & Banking Co., Ltd. (“Mizuho Trust”), were formed through the consolidation of subsidiaries of the three banks. MHHD initiated the management of the entire group by means of a Business Unit (“BU”) structure operating across the three banks. Under this structure, DKB, Fuji Bank, IBJ, Mizuho Securities, and Mizuho Trust operate as the five core member companies of MHFG. With legislative and tax code changes for corporate splits in Japan expected to be implemented by spring 2002, we will combine and reorganize the existing operations into legally separate subsidiaries, i.e., Mizuho Bank, Ltd., Mizuho Corporate Bank, Ltd., Mizuho Securities, and Mizuho Trust, according to customer segments and business lines under MHHD.