The Thakur and the Goldsmith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Sexual Health in Bangladesh

Masculinities, generations and health: Men's sexual health in Bangladesh Md Kamrul Hasan A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy r .. s ( . ' :~ - ,\ l ! S I R 1\ l I ,,\ Centre for Social Research in Health Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences UNSW Australia • February 2017 • .. PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hasan First name: Md Kamrul Other name/s: Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD Faculty: Faculty of Arts and Social School: Centre for Social Research in Health Sciences Title: Masculinities, generations and health: Men's sexual health in Bangladesh Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Together, men, masculinities and health comprise an emerging area of research, activism and policy debate. International research on men's health demonstrates how men's enactment of masculinity may be linked to their sexual health risk. However, little research to date has explored men's enactment of different forms of masculinity and men's sexual health from a social generational perspective. To address this gap, insights from Mannheim's work on social generations, Connel�s theory of masculinity, Butler's theory of gender performativity, and Alldred and Fox's work on the sexuality assemblage, were utilised to offer a better understanding of the implications of masculinities for men's sexual health. A multi-site cross-sectional qualitative study was conducted in three cities in Bangladesh. Semi-structured interviews were used to capture narratives from 34 men representing three contrasting social generations: an older social generation (growing up pre-1971), a middle social generation (growing up in the 1980s and 1990s), and a younger social generation (growing up post-2010). -

Cricket World Cup Begins Mar 8 Schedule on Page-3

www.Asia Times.US NRI Global Edition Email: [email protected] March 2016 Vol 7, Issue 3 Cricket World Cup begins Mar 8 Schedule on page-3 Indian Team: Pakistan Team: Shahid Afridi (c), Anwar Ali, Ahmed Shehzad MS Dhoni (capt, wk), Shikhar Dhawan, Rohit Mohammad Hafeez Bangladesh Team: Sharma, Virat Kohli, Ajinkya Rahane, Yuvraj Shoaib Malik, Mohammad Irfan Squad: Tamim Iqbal, Soumya Sarkar, Moham- Singh, Suresh Raina, R Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, Sharjeel Khan, Wahab Riaz mad Mithun, Shakib Al Hasan, Mushfiqur Ra- Mohammed Shami, Harbhajan Singh, Jasprit Mohammad Nawaz, Muhammad Sami him, Sabbir Rahman, Mashrafe Mortaza (capt), Bumrah, Pawan Negi, Ashish Nehra, Hardik Khalid Latif, Mohammad Amir Mahmudullah Riyad, Nasir Hossain, Nurul Pandya. Umar Akmal, Sarfraz Ahmed, Imad Wasim Hasan, Arafat Sunny, Mustafizur Rahman, Al- Amin Hossain, Taskin Ahmed and Abu Hider. Australia Team: Steven Smith (c), David Warner (vc), Ashton Agar, Nathan Coulter-Nile, James Faulkner, Aaron Finch, John Hastings, Josh Hazlewood, Usman Khawaja, Mitchell Marsh, Glenn Max- well, Peter Nevill (wk), Andrew Tye, Shane Watson, Adam Zampa England: Eoin Morgan (c), Alex Hales, Ja- Asia Times is Globalizing son Roy, Joe Root, Jos Buttler, James Vince, Ben Now appointing Stokes, Moeen Ali, Chris Jordan, Adil Rashid, David Willey, Steven Finn, Reece Topley, Sam Bureau Chiefs to represent Billings, Liam Dawson New Zealand Team: Asia Times in ALL cities Kane Williamson (c), Corey Anderson, Trent Worldwide Boult, Grant Elliott, Martin Guptill, Mitchell McClenaghan, -

Kelan Työehtosopimus 18.2.2020-31.3.2022

Kansaneläkelaitoksen ja Kelan toimihenkilöt ry:n välinen TYÖEHTOSOPIMUS 18.2.2020–31.3.2022 Kansaneläkelaitoksen ja Kelan toimihenkilöt ry:n välinen TYÖEHTOSOPIMUS KELAN TYÖEHDOT 18.2.2020–31.3.2022 Sisältö 1 TYÖSUHDE 1 § Sopimuksen soveltamisala ...................................................5 2 § Työsuhteen alkaminen, kesto ja määräaikaisuus ...................5 3 § Toimihenkilön yleiset velvollisuudet ......................................6 4 § Työnantajan yleiset velvollisuudet .........................................6 5 § Työsuhteen päättyminen, osa-aikaistaminen ja lomautus ......6 2 TYÖAIKA JA KORVAUKSET 6 § Työaika ................................................................................7 7 § Työaikapankkijärjestelmä ja liukuva työaika ..........................8 8 § Vuorotyö ..............................................................................9 9 § Ruokailu- ja kahvitauko ........................................................9 10 § Vuorokausilepo ja viikoittainen vapaa-aika..........................9 3 YLITYÖT 11 § Ylitöiden teettäminen .........................................................9 12 § Ylitöiden enimmäismäärät 1.2.2020 lukien ......................10 12 a § Työajan enimmäismäärä 1.1.2021 alkaen ......................10 13 § Ylityökorvaukset ...............................................................10 14 § Varallaolo .........................................................................11 14 a § Varallaolo IT-palveluissa ................................................12 15 § Hälytys -

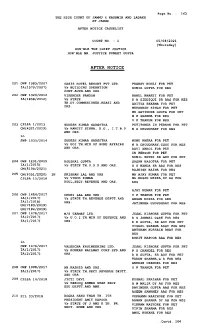

OO[Llwodo [Lns5e5 12 APPENDIX No

\'JELFARE OF THE OO[llWODO [LnS5E5 12 APPENDIX No. 1 lkJ>ressedClassrs institulions awarded maintwance grants by the State Serial num· Distrct Name and address of the institution ber Depressed Class Day Schools (Boys) 1953-54 Saharan pur . Harijan Pathshala, Mirzapur Powel, P. 0. Raypur. • .::J.. 2 bitto Harijan Pathshala, Dew ala . Ditto . , Harijan Pathshala, Santagarh. 4 Ma:rut Harijan Pathsh~la, Badhaura, P. 0. Rohta, s Ditto • • Harijan Pathshala, Kapsad, P. 0. Salava. 6 Ditto • . Mahananda Mission D. C. Primary School, lndergarhi. 1 Ditto . D. C. School Jalalpur Raghunathpur, P. 0. Marudnagar. 8 Ditto . • D. C. School, Bakarwa, P. 0. Modinagar. 9 Ditto . D. C. School, Aurangshpu'r, Diggi. 10 Bulandshahr }iarijan Pathshala, G::Jiaohii. it Agra .. • , Jatav Bir Primary School, Jiwanmandi. 12 Ditto • , Gandhi Dalit Vidyalaya, Tundli, P. 0. Tundla. 1l Ditto D. C. School, Parsonika Nagla. 14 Ditto Jatava Primary School, Nankakha. IS Ditto • , D. C. Primary School, Punja Shahi. 16 Ditto Nityanand Prakash Sachchidanand Institute, Jamuna Bridge. 11 D. C. Day School, Mandi Said Khan. IS Ditto D. C. School, Village Soolajat. P. 0. Sadar. 1~ Bareilly . Arya Kalyani Pathshala, Villat~e Ratna. P. 0. Sethal. Ditto A. K. Pathli;lhala, Village Eltanwa Sukdhdeopur. .:!1 Ditto D. C. Ar)a Kalyani Pathsh<~la, 'Balia, P. 0. Khal. Ditto A. K. Pathshala, Village Shahi, P. 0. Bhabhan. A. K. Pathshala Cantonment Sadar Bazar, Burciily. --·~ ·---· Serial num· District Name and address of the institution ber 24 B,rdlly . • D. C. Arya ·Kalyani Pathsbala, Lorry Stand, Qila. 25 Ditto . D. C. Arya Kalyani Pathshala, Kohranpur. 26 Ditto . A. K. -

Ligo-India Proposal for an Interferometric Gravitational-Wave Observatory

LIGO-INDIA PROPOSAL FOR AN INTERFEROMETRIC GRAVITATIONAL-WAVE OBSERVATORY IndIGO Indian Initiative in Gravitational-wave Observations PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA !"#!$ Indian Initiative in Gravitational wave Observations http://www.gw-indigo.org II Title of the Project LIGO-INDIA Proposal of the Consortium for INDIAN INITIATIVE IN GRAVITATIONAL WAVE OBSERVATIONS IndIGO to Department of Atomic Energy & Department of Science and Technology Government of India IndIGO Consortium Institutions Chennai Mathematical Institute IISER, Kolkata IISER, Pune IISER, Thiruvananthapuram IIT Madras, Chennai IIT, Kanpur IPR, Bhatt IUCAA, Pune RRCAT, Indore University of Delhi (UD), Delhi Principal Leads Bala Iyer (RRI), Chair, IndIGO Consortium Council Tarun Souradeep (IUCAA), Spokesperson, IndIGO Consortium Council C.S. Unnikrishnan (TIFR), Coordinator Experiments, IndIGO Consortium Council Sanjeev Dhurandhar (IUCAA), Science Advisor, IndIGO Consortium Council Sendhil Raja (RRCAT) Ajai Kumar (IPR) Anand Sengupta(UD) 10 November 2011 PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA II PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA LIGO-India EXECUTIVE SUMMARY III PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA IV PROPOSAL FOR LIGO-INDIA This proposal by the IndIGO consortium is for the construction and subsequent 10- year operation of an advanced interferometric gravitational wave detector in India called LIGO-India under an international collaboration with Laser Interferometer Gravitational–wave Observatory (LIGO) Laboratory, USA. The detector is a 4-km arm-length Michelson Interferometer with Fabry-Perot enhancement arms, and aims to detect fractional changes in the arm-length smaller than 10-23 Hz-1/2 . The task of constructing this very sophisticated detector at the limits of present day technology is facilitated by the amazing opportunity offered by the LIGO Laboratory and its international partners to provide the complete design and all the key components required to build the detector as part of the collaboration. -

District Census Handbook, Raisen, Part X

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES 10 MADHYA PR ADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART X (A) & (B) VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE AND TOWN-WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT RAISEN DISTRICT A. K. PANDYA OP THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS. MADHYA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF MADHYA PRA.DESH 1974 CONTENTS Page 1. Preface i-ii 2. List of Abbreviations 1 3. Alphabetical List of Villages 3-19 ( i ) Raisen Tahsil 3-5 ( ii) Ghairatganj Tahsil 5-7 ( iii) Begmaganj Tahsil 7-9 (iv) Goharganj Tahsil 9-12 ( v) Baraily Tahsil 12-15 (vi) Silwani Tahsil 15-17 ( vii) Udaipura Tahsil 17-19 PART A 1. Explaaatory Note 23-33 2. Village Directory (Amenities and Land-use) 34·101 ( i ) Raisen Tahsil 34-43 ( ii) Ghairatganj Tahsil 44-51 ( iii) Begamganj Tahsil 52·61 (iv) Goharganj Tahsil, 62-71 (v ) Baraily Tahsil 72-81 (vi), Silwani Tahsil 82-93 (vii ) Udaipura Tahsil 94-101 3. Appendix to Village Directery 102-103 4. Town Directory 104-107 ( i) Status, Growth History and Functional Category of Towns 104 (ii) Physical Aspects and Location of Towns 104 ( iii) Civic Finance 105 ( iv) Civic and other Amenities 105 ( v) Medical, Educational, Recreational and Cultural Facilities in Towns 106 (vi) TradCt Commerce, Industry and Banking 106 t vii) Population by R.eligion and Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes in Towns 107 PART B tJago 1. Explaaatory Note 111·112 2. Figures at a Glance 113 3. Primary Census Abstract 114·201 District Abstract 114-117 Raisen Tahsil 118·133 (Rural) Il8·133 (Urban) 132·133 Ghairatganj Tahsil 134-141 (Rural) 134·141 Begamganj Tahsil 142.153 (Rural) 142·151 (Urban) ISO-I53 Goharganj Tahsil 154-167 (Rural) 154-167 Baraily Tahsil 168-181 (Rural) 168-181 (Urban) 180·181 Silwani Tahsil 182·193 (Rural) 182-193 Udaipura Tahsil 194-201, (Rural) 194-201 LIST OF ABBREVJATIONS I. -

Causelist Dated:- 05-08-2021

Page No. : 163 THE HIGH COURT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR AND LADAKH AT JAMMU AFTER NOTICE CAUSELIST COURT NO. : 1 05/08/2021 [Thursday] HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PUNEET GUPTA AFTER NOTICE 201 OWP 1083/2007 OASIS HOTEL RESORT PVT.LTD. PRANAV KOHLI FOR PET IA(1570/2007) Vs BUILDING OPERATION SONIA GUPTA FOR RES CONT.AUTH.AND ORS. 202 OWP 1329/2012 VIRENDER PANDOH RAHUL BHARTI FOR PET IA(1858/2012) Vs STATE H A SIDDIQUI SR AAG FOR RES TH.DY.COMMSSIONER,REASI AND ADITYA SHARMA FOR PET ORS. MEHARBAN SINGH FOR PET MR.SATINDER GUOTA FOR PET M P SHARMA FOR RES O P THAKUR FOR RES 203 CPLPA 1/2013 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA PETITONER IN PERSON FOR PET CM(4321/2019) Vs RANJIT SINHA, D.G., I.T.B.P N A CHOUDHARY FOR RES AND ORS. in SWP 1035/2014 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA NONU KHERA FOR PET Vs UOI TH.MIN.OF HOME AFFAIRS N A CHOUDHARY,CGSC FOR RES AND ORS. RAVI ABROL FOR PET IN PERSON FOR PET SUNIL SETHI SR ADV FOR PET 204 OWP 1231/2015 KOUSHAL GUPTA GAGAN BASOTRA FOR PET IA(1/2015) Vs STATE TH.U.D.D.AND ORS. S S NANDA SR AAG FOR RES CM(5108/2021) RAJNISH RAINA FOR RES 205 CM(6351/2020) IN KRISHAN LAL AND ORS MR.AJAY KUMAR FOR PET CPLPA 15/2016 Vs VINOD KUMAR MR.EHSAN MIRZA,DY.AG FOR KOUL,SECY.REVENUE AND ORS. RES AJAY KUMAR FOR PET 206 OWP 1454/2017 CHUNI LAL AND ORS. -

Castes and Caste Relationships

Chapter 4 Castes and Caste Relationships Introduction In order to understand the agrarian system in any Indian local community it is necessary to understand the workings of the caste system, since caste patterns much social and economic behaviour. The major responses to the uncertain environment of western Rajasthan involve utilising a wide variety of resources, either by spreading risks within the agro-pastoral economy, by moving into other physical regions (through nomadism) or by tapping in to the national economy, through civil service, military service or other employment. In this chapter I aim to show how tapping in to diverse resource levels can be facilitated by some aspects of caste organisation. To a certain extent members of different castes have different strategies consonant with their economic status and with organisational features of their caste. One aspect of this is that the higher castes, which constitute an upper class at the village level, are able to utilise alternative resources more easily than the lower castes, because the options are more restricted for those castes which own little land. This aspect will be raised in this chapter and developed later. I wish to emphasise that the use of the term 'class' in this context refers to a local level class structure defined in terms of economic criteria (essentially land ownership). All of the people in Hinganiya, and most of the people throughout the village cluster, would rank very low in a class system defined nationally or even on a district basis. While the differences loom large on a local level, they are relatively minor in the wider context. -

List of Scheduled Castes

List of Scheduled Castes List of Scheduled Castes notified (after addition/deletion)as per the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950, as amended vide Modification Order 1956, Amendment Act, 1976 and the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order (Amendment) Act 2002 No. 25 dated 27.5.2002. of Ministry of Law, Justice and Company Affairs, read with The Constitution (SCs) Order (Second Amendment) Act, 2002 No. 61 of 2002 dated 18.12.2002 of Ministry of Law & Justice republished vide Notification No. 7797-I- Legis-5/2002-L dated 7.6.2003 of Law Deptt, Govt. of Orissa and, vide Gazette of India No.381dt.30.8.2007, Gazette of India No.40 dt.18.12.2014 and Gazette of India No.7 dt.23.03.2015. Sl. Scheduled Castes No. 1. Adi-Andhra 2 Amant, Amat, Dandachhatra Majhi, Amata, Amath 3. Audhelia 4. Badaik 5. Bagheti, Baghuti 6. Bajikar 7. Bari 8. Bariki 9. Basor, Burud 10. Bauri, Buna Bauri, Dasia Bauri 11. Bauti 12. Bavuri 13. Bedia, Bejia, Bajia 14. Beldar 15. Bhata 16. Bhoi 17. Chachati 18. Chakali 19. Chamar, Mochi, Muchi, Satnami,Chamara, Chamar-Ravidas,Chamara-Rohidas.. 20. Chandala 21. Chandhai Maru 22. Deleted vide Constitution (SCs) Order(Amendment) Act, 2002. No. 25 of 2002 23. Dandasi 24. Dewar, Dhibara, Keuta, Kaibarta 25. Dhanwar 26. Dhoba, Dhobi, Rajak, Rajaka 27. Dom, Dombo, Duria Dom, Adhuria Dom, Adhuria Domb 28. Dosadha 29. Ganda 30. Ghantaragada Ghantra 31. Ghasi, Ghasia 32. Ghogia Sl. Scheduled Castes No. 33. Ghusuria 34. Godagali 35. Godari 36. Godra 37. Gokha 38. Gorait, Korait 39. Haddi, Hadi, Hari 40. -

Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in a Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin, Monsoon Article 7 1984 1984 Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F. Winkler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Winkler, Walter F. (1984) "Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol4/iss2/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ... ORAL HISTORY AND THE EVOLUTION OF THAKUR! POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN A SUBREGION OF FAR WESTERN NEPAL Walter F. Winkler Prologue John Hitchcock in an article published in 1974 discussed the evolution of caste organization in Nepal in light of Tucci's investigations of the Malia Kingdom of Western Nepal. My dissertation research, of which the following material is a part, was an outgrowth of questions John had raised on this subject. At first glance the material written in 1978 may appear removed fr om the interests of a management development specialist in a contemporary Dallas high technology company. At closer inspection, however, its central themes - the legitimization of hierarchical relationships, the "her o" as an organizational symbol, and th~ impact of local culture on organizational function and design - are issues that are relevant to industrial as well as caste organization. -

The GREAT ARC 1-23.Qxd 6/24/03 5:27 PM Page 2

1-23.qxd 6/24/03 5:27 PM Page 1 The GREAT ARC 1-23.qxd 6/24/03 5:27 PM Page 2 SURVEY of INDIA AN INTRODUCTION Dr. Prithvish Nag, Surveyor General of India he Survey of lndia has played an invaluable respite, whether on the slopes of the Western Ghats, role in the saga of India’s nation building. the swampy areas of the Sundarbans, ponds and TIt has seldom been realized that the founding tanks, oxbow lakes or the meandering rivers of of modern India coincides with the early activities of Bengal, Madurai or the Ganga basin. Neither were this department, and the contribution of the Survey the deserts spared, nor the soaring peaks of the has received little emphasis - not even by the Himalayas, the marshlands of the Rann of Kutch, department itself. Scientific and development rivers such as the Chambal in the north and Gandak initiatives in the country could not have taken place to the east, the terai or the dooars.With purpose and without the anticipatory actions taken by the dedication the intrepid men of the Survey confronted department, which played an indispensable the waves of the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal, dust pioneering role in understanding the country’s storms of Rajasthan, cyclones of the eastern coast, the priorities in growth and defense. cold waves of the north and the widespread The path-breaking activities of the Survey came, monsoons and enervating heat. of course, at a price and with immense effort. The It was against this price, and with the scientific measurement of the country, which was the determination and missionary zeal of the Survey’s Survey’s primary task, had several ramifications. -

Cultures of Food and Gastronomy in Mughal and Post-Mughal India

Cultures of Food and Gastronomy in Mughal and post-Mughal India Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von: Divya Narayanan Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Gita Dharampal-Frick Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Heidelberg, Januar 2015 Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................... iii Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………… v Note on Transliteration………………………………………………………… vi List of Figures, Maps, Illustrations and Tables……………………………….. vii Introduction........................................................................................................... 2 Historiography: guiding lights and gaping holes………………………………… 3 Sources and methodologies………………………………………………………. 6 General background: geography, agriculture and diet…………………………… 11 Food in a cross-cultural and transcultural context………………………………...16 Themes and questions in this dissertation: chapter-wise exposition………………19 Chapter 1: The Emperor’s Table: Food, Culture and Power………………... 21 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 21 Food, gender and space: articulations of imperial power………………………... 22 Food and the Mughal cityscape………………………………………………...... 35 Gift-giving and the political symbolism of food………………………………… 46 Food, ideology and the state: the Mughal Empire in cross-cultural context……...53 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...57 Chapter 2: A Culture of Connoisseurship……………………………………...61 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….