Chapter 17 Communities on the Edge of Civilisation Fiona Coward And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OAR Strategy (2020-2026)

OAR Strategy 2020-2026 Deliver NOAA’s Future OAR Strategic Plan | 1 2 | OAR Strategic Plan Contents 4 Introduction 5 Vision and Mission 5 Values 6 Organization 8 OAR’s Changing Operating Landscape 10 Strategic Approach 13 Goals and Objectives 14 Explore the Marine Environment 15 Detect Changes in the Ocean and Atmosphere 16 Make Forecasts Better 17 Drive Innovative Science 18 Appendix I: Strategic Mapping 19 Appendix II: Congressional Mandates OAR Strategic Plan | 3 Introduction Introduction — A Message from Craig McLean Message from Craig McLean The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was created to include a major Line Office, Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR), focused on determining the relationship between the atmosphere and the ocean. That task has been at the core of OAR’s work for the past half century, performed by federal and academic scientists and in the proud company of our other Line Offices of NOAA. Principally a research organization, OAR has contributed soundly to NOAA’s reputation as being among the finest government science agencies worldwide. Our work is actively improving daily weather forecasts and severe storm warnings, furthering public understanding of our climate future and the global role of the ocean, and helping create more resilient communities for a sound economy. Our research advances products and services that protect lives and livelihoods, the economy, and the environment. The research landscape of tomorrow will be different from that of today. There will likely be additional contributors to the sciences we study, including more involvement from the private sector, increased philanthropic participation, and greater academic integration. -

Oar Manual(PDF)

TABLE OF CONTENTS OAR ASSEMBLY IMPORTANT INFORMATION 2 & USE MANUAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS 3 ASSEMBLY Checking the Overall Length of your Oars .......................4 Setting Your Adjustable Handles .......................................4 Setting Proper Oar Length ................................................5 Collar – Installing and Positioning .....................................5 Visit concept2.com RIGGING INFORMATION for the latest updates Setting Inboard: and product information. on Sculls .......................................................................6 on Sweeps ...................................................................6 Putting the Oars in the Boat .............................................7 Oarlocks ............................................................................7 C.L.A.M.s ..........................................................................7 General Rigging Concepts ................................................8 Common Ranges for Rigging Settings .............................9 Checking Pitch ..................................................................10 MAINTENANCE General Care .....................................................................11 Sleeve and Collar Care ......................................................11 Handle and Grip Care ........................................................11 Evaluation of Damage .......................................................12 Painting Your Blades .........................................................13 ALSO AVAILABLE FROM -

OAR 437, Division 2, Subdivision Z, Asbestos

Oregon Administrative Rules Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Division ASBESTOS Z OAR 437, DIVISION 2 GENERAL OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH RULES SUBDIVISION Z – TOXIC AND HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES 437-002-0360 Adoption by Reference. In addition to, and not in lieu of, any other safety and health codes contained in OAR Chapter 437, the Department adopts by reference the following federal regulations printed as part of the Code of Federal Regulations, 29 CFR 1910, in the Federal Register: (2) 29 CFR 1910.1001 Asbestos, published 3/26/12, FR vol. 77, no. 58, p. 17574. These standards are on file at the Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Division, Oregon Department of Consumer and Business Services, and the United States Government Printing Office. Stat. Auth.: ORS 654.025(2) and 656.726(4). Stats. Implemented: ORS 654.001 through 654.295. Hist: APD Admin. Order 13-1988, f. 8/2/88, ef. 8/2/88 (Benzene). APD Admin. Order 14-1988, f. 9/12/88, ef. 9/12/88 (Formaldehyde). APD Admin. Order 18-1988, f. 11/17/88, ef. 11/17/88 (Ethylene Oxide). APD Admin. Order 4-1989, f. 3/31/89, ef. 5/1/89 (Asbestos-Temp). APD Admin. Order 6-1989, f. 4/20/89, ef. 5/1/89 (Non-Asbestiforms-Temp). APD Admin. Order 9-1989, f. 7/7/89, ef. 7/7/89 (Asbestos & Non-Asbestiforms-Perm). APD Admin. Order 11-1989, f. 7/14/89, ef. 8/14/89 (Lead). APD Admin. Order 13-1989, f. 7/17/89, ef. 7/17/89 (Air Contaminants). -

Preliminary Program Draft (March

NEAA Preliminary Program as of 24 March 2015 Poster Session – Saturday all Day (Poster) Priscilla H. Montalto (Skidmore College) Archaeological Methods of Recovery at the Sucker Brook Site [email protected] (Poster) Jake DeNicola (Skidmore College) The Stigmatization of Postindustrial Urban Landscapes and Communities in Upstate, New York [email protected] (Poster) Rebecca Morofsky (Skidmore College) The Stigmatization of Postindustrial Urban Landscapes and Communities in Upstate, New York [email protected] (Poster) Rachel Tirrell, Senior Author, (Franklin Pierce University), Courtney Cummings, Kelsey Devlin, Brian Kirn, Cooper Leatherwood, Rebecca Nystrom, Katherine Pontbriand, (all from Franklin Pierce University) [email protected] (Poster) Ammie Mitchell (Buffalo University) Ceramic Petrography and Color Symbolism in Northeastern Archaeology [email protected] (Poster) Kate Pontbriand (Franklin Pierce University) The History of Tranquility Farm [email protected] Saturday Morning 9-11 Northeastern Anthropology Panel Chairs: Kelsey Devlin & Cory Atkinson Grace Belo (Bridgewater State University) A Walk Through Time with the Boats Archaeological Site of Dighton Massachusetts Cory Atkinson (SUNY Binghamton) A Preliminary Analysis of Paleoindian Spurred End Scrapers from the Corditaipe Site in Central New York [email protected] Kimberly H. Snow (Skidmore College) Ceramic Wall Thinning at Fish Creek-Saratoga Lake During the Late Woodland Period [email protected] Gail R. Golec (Monadnock Archaeological Consulting, LLC.) Folklore versus Forensics: how the historical legend of one NH town held up to modern scientific scrutiny [email protected] Kelsey Devlin (Franklin Pierce University) Just Below the Surface: Historic and Archaeological Analysis of Submerged Sites in Lake Winnipesaukee [email protected] John M. Fable, William A. Farley, and M. -

The Distribution of Obsidian in the Eastern Mediterranean As Indication of Early Seafaring Practices in the Area a Thesis B

The Distribution Of Obsidian In The Eastern Mediterranean As Indication Of Early Seafaring Practices In The Area A Thesis By Niki Chartzoulaki Maritime Archaeology Programme University of Southern Denmark MASTER OF ARTS November 2013 1 Στον Γιώργο 2 Acknowledgments This paper represents the official completion of a circle, I hope successfully, definitely constructively. The writing of a Master Thesis turned out that there is not an easy task at all. Right from the beginning with the effort to find the appropriate topic for your thesis until the completion stage and the time of delivery, you got to manage with multiple issues regarding the integrated presentation of your topic while all the time and until the last minute you are constantly wondering if you handled correctly and whether you should have done this or not to do it the other. So, I hope this Master this to fulfill the requirements of the topic as best as possible. I am grateful to my Supervisor Professor, Thijs Maarleveld who directed me and advised me during the writing of this Master Thesis. His help, his support and his invaluable insight throughout the entire process were valuable parameters for the completion of this paper. I would like to thank my Professor from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Nikolaos Efstratiou who help me to find this topic and for his general help. Also the Professor of University of Crete, Katerina Kopaka, who she willingly provide me with all of her publications –and those that were not yet have been published- regarding her research in the island of Gavdos. -

Fire Season Requirements for Industrial Operations

FIRE SEASON REQUIREMENTS The following fire season requirements become effective when fire season is declared in each Oregon Department of Forestry Fire Protection District, including those protected by associations (DFPA, CFPA, WRPA). NO SMOKING (477.510) No smoking while working or traveling in an operation area. HAND TOOLS (ORS 477.655, OAR 629-43-0025) Supply hand tools for each operation site - 1 tool per person with a mix of pulaskis, axes, shovels, hazel hoes. Store all hand tools for fire in a sturdy box clearly identified as containing firefighting tools. Supply at least oneor boxf each operation area. Crews of 4 or less are not required to have a fire tools box as long as each person has a shovel, suitable for fire-fighting and available for immediate use while working on the operation. FIRE EXTINGUISHERS (ORS 477.655, OAR 629-43-0025) Each internal combustion engine used in an operation, except power saws, shall be equipped with a chemical fire extinguisher rated as not less than 2A:10BC (5 pound). POWER SAWS ( ORS 477.640, OAR 629-043-0036) Power saws must meet Spark Arrester Guide specifications - a stock exhaust system and screen with < .023 inch holes. The following shall be immediately available for prevention and suppression of fire: One gallon of water or pressurized container of fire suppressant of at least eight ounce capacity 1 round pointed shovel at least 8 inches wide with a handle at least 26 inches long The power saw must be moved at least 20' from the place of fueling before it is started. -

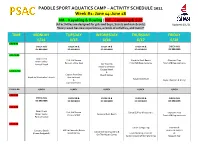

PADDLE SPORT AQUATICS CAMP – ACTIVITY SCHEDULE 2021 Week #1: June 14-June 18

PADDLE SPORT AQUATICS CAMP – ACTIVITY SCHEDULE 2021 Week #1: June 14-June 18 AM – Kayaking & Rowing | PM – Canoeing & SUP (All activities are designed for girls and boys, Scouts and non-Scouts) Updated 4/1/21 *Every week has new experiences, a remix of activities, and more!* TIME MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 6/14 6/15 6/16 6/17 6/18 8:30-8:45 CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER 8:45-10:00 Swim Check First Aid Review Kayak to Dock Beach Olympics Prep Water Safety Parts of a Row Boat Finish MB Requirements Finish MB Requirements Parts of Kayak Oar Board & Kayak to Q Beach Capsize Kayak 10:00-12:00 & Capsize Row Boat Beach Games Kayak to Windsurfer’s Beach Row to Beach Kayak Basketball & Kayak Olympics & Relays Oar Board Intro 12:00-1:00 LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH LUNCH 1:00-1:15 CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & CHECK-IN & ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER ICE BREAKER 1:15-2:30 Swim Check First Aid Review Canoe/SUP to Windsurfer’s Olympics Prep Water Safety Canoe to Dock Beach Parts of a SUP Finish MB Requirements Parts of Canoe 2:30-4:30 Canoe Sponge Tag SURFING & Canoe to Beach SUP to Channels/Beach BEACH OLYMPICS Canoe Skill Development & (Canoe Dodgeball) Beach Games Finish MB Requirements @ On-The-Water Games Switch Watercraft for return trip Newport Pier PADDLE SPORT AQUATICS CAMP – ACTIVITY SCHEDULE 2021 Week #2: June 21-June 25 AM – Canoeing & SUP | PM – Kayaking & Rowing (All activities are designed for girls and boys, -

The Assabet River Pocket Guide a Recreation Guide to the Assabet River OAR

The Assabet River Pocket Guide A Recreation Guide to the Assabet River OAR The Assabet River “A more lovely stream than this,” Nathaniel Hawthorne said of the Assabet River, “has never flowed on earth, except to lave the interior regions of a poet’s imagination.” Much of the river is still beauti- ful today, with surprisingly remote and unspoiled sections. In 1999, four miles of the Assabet were designated under the federal Wild and Scenic Rivers program. The Assabet River begins in Westborough, flowing north for 31 miles through Northborough, Marlborough, Berlin, Hudson, Stow, Maynard, and Acton until it joins the Sudbury River in the town of Concord to form the Concord River. The river is home to abundant wildlife, including great blue herons, river otters, osprey, and painted turtles. Despite an abundance of dams, dif- Helpful Resources ficult passage in the upper reaches, and even a bit of seasonal whitewater, the Books: Assabet offers some easy and interest- The Concord, Sudbury, and Assabet Rivers: ing paddles for the beginning canoeist A guide to canoeing, wildlife and history. or kayaker. We especially recommend By Ron McAdow. Bliss Publishing Company, the three trips highlighted in purple on the map. Marlborough, MA. 1997. Available through OAR. River Safety Websites: Although the majority of the Assabet OAR: www.assabetriver.org River flows gently, please be aware that Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge: dams, high water (and low bridges), assabetriver.fws.gov downed trees, and seasonal rapids can Assabet River Rail Trail: www.arrtinc.org pose serious hazards to boaters. Please Mass Audubon: www.massaudubon.org be careful and wear a life jacket. -

Prehistoric Britain

Prehistoric Britain Plated disc brooch Kent, England Late 6th or early 7th century AD Bronze boars from the Hounslow Hoard 1st century BC-1st century AD Hounslow, Middlesex, England Visit resource for teachers Key Stage 2 Prehistoric Britain Contents Before your visit Background information Resources Gallery information Preliminary activities During your visit Gallery activities: introduction for teachers Gallery activities: briefings for adult helpers Gallery activity: Neolithic mystery objects Gallery activity: Looking good in the Neolithic Gallery activity: Neolithic farmers Gallery activity: Bronze Age pot Gallery activity: Iron Age design Gallery activity: An Iron Age hoard After your visit Follow-up activities Prehistoric Britain Before your visit Prehistoric Britain Before your visit Background information Prehistoric Britain Archaeologists and historians use the term ‘Prehistory’ to refer to a time in a people’s history before they used a written language. In Britain the term Prehistory refers to the period before Britain became part of the Roman empire in AD 43. The prehistoric period in Britain lasted for hundreds of thousands of years and this long period of time is usually divided into: Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic (sometimes these three periods are combined and called the Stone Age), Bronze Age and Iron Age. Each of these periods might also be sub-divided into early, middle and late. The Palaeolithic is often divided into lower, middle and upper. Early Britain British Isles: Humans probably first arrived in Britain around 800,000 BC. These early inhabitants had to cope with extreme environmental changes and they left Britain at least seven times when conditions became too bad. -

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Description of Office of Air and Radiation (OAR) Partnership and Community Programs

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Description of Office of Air and Radiation (OAR) Partnership and Community Programs This document includes brief descriptions of partnership and community programs that U.S. EPA OAR manages and/or participates in as of fall 2009. This document does not include programs that are primarily supported by EPA Regional Offices. The descriptions contained in this document have been extracted from an internal EPA work group report on partnership and community‐based programs completed on November 10, 2009. Contents: 1. OAR/HQ Partnership and Community Programs 1.1 OAR/HQ partnership programs 1.2 OAR/HQ community based programs (place‐based activities) 1.3 OAR information partnerships 1.4 OAR research partnerships 2. Other EPA & Federal Government Partnerships in which OAR Participates 2.1 EPA partnership programs 2.2 EPA community programs that OAR supports 2.3 Other Federal partnerships OAR supports 3. OAR International Partnership Activities 3.1 OAR International Partnerships 3.2 International partnerships in which OAR participates DRAFT; 6/21/10 1 1. OAR/HQ Partnership and Community Programs 1.1 OAR/HQ partnership programs Climate Leaders Climate Leaders is an EPA industry‐government partnership that works with companies to develop comprehensive climate change strategies. Partner companies commit to reducing their impact on the global environment by completing a corporate‐wide inventory of their greenhouse gas emissions based on a quality management system, setting aggressive reduction goals, and annually reporting their progress to EPA. Through program participation, companies create a credible record of their accomplishments and receive EPA recognition as corporate environmental leaders. -

Lighter & Stronger Oar Shaft It Is More by Accident Than Design I Have

Lighter & Stronger Oar Shaft It is more by accident than design I have arrived at an efficient and radical way of making a stiff, light shaft. The cross sectional shape goes by the rather awkward name of “isosceles trapezoid” (an isosceles triangle with the apex cut off). It was while I was playing around with different shapes that I was surprised to find that such a shape could rotate in the oarlock, as well as provide a flat section to match the D-shape oarlock. Since it had many other advantages I have been making oars using this shape. Considerations: Most oarlocks are designed for a round less than two-inch diameter shaft. When the leather protector is added, the shaft is reduced to 1 7/8”. Some fittings reduce it to 1 ¾” at the oarlock and this dictates the dimensions of the rest of the oar for a given length. Most properly designed oars will have approximately the same volume. Hence they need a light strong timber. Expensive and hard to get, Sitka Spruce, is generally selected as the ideal choice. Active and passive planes: the plane of the oar vertical to the water (passive plane) only needs to be strong enough to lift the blade in and out of the water, while that parallel to the water (active plane) needs to be strong and stiff to resist bending and breakage of the oar. The passive plane of a round oar is wastefully stiff. There is no reason why a heavier timber cannot be made thinner in the passive plane as long as it is still functional. -

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Ian Morris

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT Ian Morris © Ian Morris Stanford University October 2010 http://www.ianmorris.org 1 Contents List of Tables, Maps, Figures, and Graphs 4 1 Introduction 7 2 Formal Definition 9 3 Core Assumptions 10 3.1 Quantification 10 3.2 Parsimony 10 3.3 Traits 10 3.4 Criteria 11 3.5 The focus on East and West 11 3.6 Core regions 12 3.7 Measurement intervals 16 3.8 Approximation and falsification 16 4 Core Objections 17 4.1 Dehumanization 17 4.2 Inappropriate definition 17 4.3 Inappropriate traits 17 4.4 Empirical errors 21 5 Models for an Index of Social Development 22 5.1 Social development indices in neo-evolutionary anthropology 22 5.2 The United Nations Human Development Index 23 6 Trait Selection 25 7 Methods of Calculation 26 8 Energy Capture 28 8.1 Energy capture, real wages, and GDP, GNP, and NDI per capita 28 8.2 Units of measurement and abbreviations 32 8.3 The nature of the evidence 33 8.4 Estimates of Western energy capture 35 8.4.1 The recent past, 1700-2000 CE 36 8.4.2 Classical antiquity (500 BCE–200 CE) 39 8.4.3 Between ancient and modern (200–1700 CE) 50 8.4.3.1 200-700 CE 50 8.4.3.2 700-1300 CE 53 8.4.3.3 1300-1700 CE 55 8.4.4 Late Ice Age hunter-gatherers (c. 14,000 BCE) 57 8.4.5 From foragers to imperialists (14,000-500 BCE) 59 8.4.6 Western energy capture: discussion 73 2 8.5 Estimates of Eastern energy capture 75 8.5.1 The recent past, 1800-2000 CE 79 8.5.2 Song dynasty China (960-1279 CE) 83 8.5.3 Early modern China (1300-1700 CE) 85 8.5.4 Ancient China (200 BCE-200 CE) 88 8.5.5 Between ancient and medieval (200-1000 CE) 91 8.5.6 Post-Ice Age hunter-gatherers (c.