P R O D U C T IO N a N D M a R K E T in G O F C O T T O N ; V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abundance and Fluctuation in Spider Diversity in Citrus Fruits from Located in Vicinity of Faisalabad Pakistan

June 2016 Vol. 23 No. 2 59-64 ScienceDirect Journal of Northeast Agricultural University (English Edition) Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Abundance and Fluctuation in Spider Diversity in Citrus Fruits from Located in Vicinity of Faisalabad Pakistan Maqsood I1, Mohsin S B1, Li Yi-jing1, Tang Li-jie1, Saleem K M2, Khalil U R3, Shahla A3, Aoun Bukhari4, and S S Jamal5 1 College of Veterinary Medicine, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China 2 Department of Wild Life and Fisheries, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan 3 College of Resources and Environment, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China 4 Department of Entomology, University of Punjab, Pakistan 5 School of Management, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China Abstract: Spiders for the present study were collected from different fruit gardens (i.e. citrus) located at various localities (i.e., Tehsil Samundri, Jaranwala, Tandlianwala and Faisalabad) of District Faisalabad, Pakistan. Spiders belonging to six families and 33 species were captured from the two fruit gardens during the one year of this study. The citrus fruits garden was found to be best populated habitat as compared to other fruit garden. These sites were sampled by using pitfall traps; each month for five consecutive days from September 2010 to March 2011. As a result, 1 054 specimens were captured representing six families viz: lycosidae, thomosidae, gnaphosidae, saltisidae, araneidae and clubionidae. Lycosidae was more abundant, while clubionidae was less diverse during the study. Maximum population fluctuation among the spider specimens showed during the months from September and October, while the least abundance of spider specimens was reordered during June, November and December. -

FIRMS in AOR of RD PUNJAB Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD

Appendix-A FIRMS IN AOR OF RD PUNJAB Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD 1 M/s A.A Textile Processing Industries, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 2 M/s A.B Exports (Pvt) Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 3 M/s A.M Associates, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 4 M/s A.M Knit Wear, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 5 M/s A.S Chemical, Multan Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 6 M/s A.T Impex, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 7 M/s AA Brothers Chemical Traders, Sialkot Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 8 M/s AA Fabrics, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 9 M/s AA Spinning Mills Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 10 M/s Aala Production Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 11 M/s Aamir Chemical Store, Multan Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 12 M/s Abbas Chemicals, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab M/s Abdul Razaq & Sons Tezab and Spray Centre, 13 Hydrochloric Acid Punjab Toba Tek Singh 14 M/s Abubakar Anees Textiles, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 15 M/s Acro Chemicals, Lahore Toluene & MEK Punjab 16 M/s Agritech Ltd, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 17 M/s Ahmad Chemical Traders, Muridke Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 18 M/s Ahmad Chemmicals, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 19 M/s Ahmad Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Khanewal Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 20 M/s Ahmed Chemical Traders, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 21 M/s AHN Steel, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 22 M/s Ajmal Industries, Kamoke Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 23 M/s Ajmer Engineering Electric Works, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 24 M/s Akbari Chemical Company, -

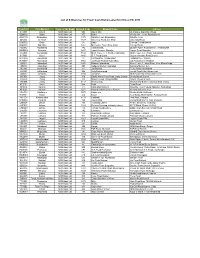

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

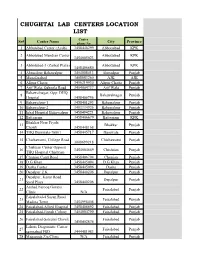

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

List of Applicants Who Submitted Incomplete Application Forms to the Fisheries Department, Haryana, Panchkula for the Post of Fisherman-Cum- Watchman

List of Applicants who submitted incomplete Application Forms to the Fisheries Department, Haryana, Panchkula for the post of Fisherman-cum- Watchman. Sr. No. Name and Father Name Address District State Date of Birth Cate. Quali. Experience Training Other Remarks 1 Aadesh Kumar S/o Ved Parkash VPO Dhos Kaithal Haryana 04-06-1989 BC-B 8th No No 2 Aalam Khan S/o Israil VPO Dhiranki, Hatin Palwal Haryana 01-03-1993 BC-B B.A. No No 3 Aalok Babu S/o Raju Babu #7, New Vivek Vihar Ambala Haryana 01-05-1986 SC 10th No No 4 Aamir Khan S/o Jahir Ahmad VPO Charoda, Tawdu Mewat Haryana 20-09-1993 BC-B 12th No No DOB Certificate also not attached. 5 Aarif Khan S/o Rati Khan VPO Dhankli, Ujina Mewat Haryana 02-10-1998 BC-A 10th No No 6 Aas Mohammad s/o Mehboob Ali Vill Dhanoura ,Murad Nagar Amroha Uttar 01-05-1989 Gen. 8th No No Pradesh 7 Aashish Kumar S/o Lalmani Vpo. Bighana, Allahabad Uttar 05-03-1988 SC 8th No No Pradesh 8 Aashish S/o Mahavir Singh VPO Talav Jhajjar Haryana 17-08-1987 Gen. B.A. No No 9 Abdul Quarim S/o Ismyal Khan VPO Dhouj Faridabad Haryana 13-05-1974 Gen. 8th No No 10 Abdussalam Quareshi S/o Ali Husain VPO Police Line Sawroop Nagar , Sitapur Uttar 12-07-1982 BC-A 10th No No Caste Certificate also not attached. Pradesh 11 Abhijeet Sen Gupta S/o Dev Brat 107/177, Allopshankari Apartment, Allahabad Uttar 15-04-1991 Gen. -

WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT

IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT 2 | MEDHA BISHT Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-17-8 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Monograph are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. First Published: April 2013 Price: Rs. 280/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Layout & Cover by: Vaijayanti Patankar & Geeta Printed at: M/S A. M. Offsetters A-57, Sector-10, Noida-201 301 (U.P.) Mob: 09810888667 E-mail: [email protected] WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 6 PART I Chapter One ................................................................. -

Society1 in Lower Chenab Colony: a Case Study of Toba Tek Singh (1900-1947)

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 55, Issue No. 2 (July - December, 2018) Nayyer Abbas * Tahir Mahmood ** Fatima Riffat*** Constructing ‘hydraulic’ Society1 in Lower Chenab Colony: A Case Study of Toba Tek Singh (1900-1947) Abstract This paper focuses on agricultural colonization projects from 1885 to 1947 in Punjab. It will be helpful to understand agricultural colonization of the Punjab by the British government and further to establish a link with migration trends during the partition of Punjab in 1947. Among other canal colonies areas, Lower Chenab Colony greatly transformed the agricultural economy of the Punjab. The case study research material has been primarily drawn from the District Colony Record Office Toba Tek Singh, Punjab Archives Lahore and the British Library. It shows that social engineering through which British government developed Toba Tek Singh, constructed a hydraulic society, controlled by the colonial state through the control of canal waters. Its specific composition also gives clue to the migration trends during the Partition of Punjab in 1947. The local non-Muslims’ (Hindu and Sikh) previous family links with the East Punjab became one of the major factors in their migration to India. Key Words: Hydraulic society, Toba Tek Singh, Social engineering, migration, Lower Chenab colony Introduction History of the canal colonies in the Punjab during colonial period had been researched by the number of historians from different aspects of this project. David Gilmartin analyzed the Punjabi migration to the Canal Colonies during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and provided a critical link ‘between village organization and sate power that lay at the heart of colonial rule’.2 D. -

List of E-Branches for Fresh Cash Disbursement for Eid-Ul-Fitr 2016

List of E-Branches for Fresh Cash Disbursement for Eid-ul-Fitr 2016 Branch ID City/District Name of the Bank Branch Code Branch Name Address ATK004 Attock MCB Bank Ltd 598 Attock City Dr.Ghulam Jillani Barq Road BDN002 Badin MCB Bank Ltd 875 Badin 118,Quaid-e-Azam Road Branch BWP006 Bahawalpur MCB Bank Ltd 1476 Satellite Town Bahawalpur Satellite Town DIK006 D.I Khan MCB Bank Ltd 1637 University Road, D.I. Khan University Road DAD002 Dadu MCB Bank Ltd 95 Dadu Cinema Chowk Branch DGK001 DG Khan MCB Bank Ltd 1221 Microwave Tower D.G. Khan College Road FSD002 Faisalabad MCB Bank Ltd 342 Tandlianwala Quaid-e-Azam Road Branch, Tandlianwala GWD002 Gawadar MCB Bank Ltd 1487 Jinnah Avenue, Gwadar Airport Road Gawadar GUJ008 Gujranwala MCB Bank Ltd 1632 MCB Tower, G.T. Road, Gujranwala MCB Tower, G.T. Road, Gujranwala GJT003 Gujrat MCB Bank Ltd 1410 G.T. Road Gujrat Gulzar-e-Madina Road Branch HYD006 Hyderabad MCB Bank Ltd 121 Latifabad No.7 Hyderabad Latifabad No.7 Branch HYD007 Hyderabad MCB Bank Ltd 1082 Jail Road Hirabad Hyderabad Jail Road Branch Hirabad ISB002 Islamabad MCB Bank Ltd 1641 Khanna, Islamabad Amin Centre, Lehtrar Road, Near Khana Bridge ISB006 Islamabad MCB Bank Ltd 597 Aabpara Market Islamabad Aabpara Market, G-6 JAC001 Jacobabad MCB Bank Ltd 81 Jacobabad Tower Road Jacobabad JAF001 Jaffarabad MCB Bank Ltd 562 Usta Muhammad Jinnah Road Usta Muhammad JAM002 Jamshoro MCB Bank Ltd 1749 Jamshoro MCB Branch Near Bismillah Centre JHG004 Jhang MCB Bank Ltd 419 Ghalla Mandi Toba Road Jhang Saddar Ghalla Mandi Branch JHG005 Jhang MCB Bank Ltd 335 Nawaz Chowk Jhang Saddar Nawaz Chowk Branch JHG006 Jhang MCB Bank Ltd 1117 Shorkot City Shorkot City Branch, Shorkot, Distt. -

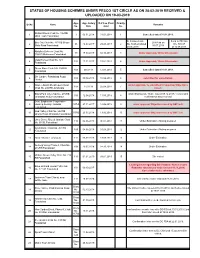

Status of Housing Schemes Under Fesco 1St Circle As on 28-02-2019 Received & Uploaded on 19-03-2019

STATUS OF HOUSING SCHEMES UNDER FESCO 1ST CIRCLE AS ON 28-02-2019 RECEIVED & UPLOADED ON 19-03-2019 App. App. Entery D.V Fee (Paid Priority Sr.No Name Remarks No. Date date) No. Al-Basit Block Chak No. 196/RB 1 1 03.01.2014 31.01.2014 1 Cancelled dated 31.01.2019. Millat Town Faisalabad. D. N issued vide Send to PD Vide Bilal City Chak No. 197/RB Bhage D.N Paid on 2 98 16.08.2017 29.09.2017 2 No. 5825-28 dated No. 794-97 Wala Road Faisalabad 06.07.2018 20.06.2018 dt 15.08.2018. Abdullah Defense Chak No. 3 99 17.08.2017 02.10.2017 3 Under Approval./ Under Discussion 299/RB Makkuana Faisalabad Vista Homes Chak No. 121 4 102 17.11.2017 31.01.2018 4 Under Approval./ Under Discussion Faisalabad Green Block Chak NO. 204/RB 5 103 09.03.18 12.04.2018 5 Cancelled dated 31.01.2019. Faisalabad Din Garden, Faisalabad Road, 6 105 09.04.2018 16.04.2018 6 submitted for cancellation. Chiniot Wadi-e-Sitara Sheikhupura Road under approval./ re-submitted for approval/ Objections 7 104 19.03.18 25.04.2018 7 Chak No. 200/RB Jaranwala raised. Sitara Park City Chak No. 215/RB Under Estimation./ Notice issued 05.12.2018./ revised and 8 106 12.04.2018 11.05.2018 8 Jaranwala Road Faisalabad confirmation also received. Govt. Employees Cooperative 9 Housing Society, Gatwala 107-A 27.11.2017 12.06.2018 9 under approval/ Objection raised by GM.Tech. -

Faisalabad - Consolidated ADP 2012-13

CDG Faisalabad - Consolidated ADP 2012-13 Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012 -13 Faisalabad (City District Government, WASA and FDA 1 CDG Faisalabad - Consolidated ADP 2012-13 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... 5 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Consolidated ADP 2012-13 Faisalabad ................................................................................................... 9 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13-By Entity ....... 11 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13-By Sector ...... 14 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13-By Category .. 16 Faisalabad – Summary of Consolidated Annual Development Programme 2012-13- By Commencement Period .................................................................................................................... 18 City District Government, Faisalabad ................................................................................................... 21 Summary of Annual Development Programme 2012-13 ................................................................. 23 Annual Development Programme 2012-13 - by Category ................................................................ 25 Annual Development Programme 2012-13 -

Sr. No. Roll.No. Name & Adress Subject 3001 3002 3003 3004

ONE RESEARCH OFFICER IN THE SUBJECT OF PARASITOLOGY, CENTRAL HI-TECH LABORATORY. Sr. Roll.No. Name & Adress Subject No. 1. Mr. Abdul Qudoos, PARASITOLOGY Research Officer, Central Hi-Tech. Lab., 3001 University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. 2. Mr. Aamir Saleem, PARASITOLOGY S/o Muhammad Saleem Akhtar, Mohallah Ijaz Shaheed, Garh Maharaja, District Jhang. 3002 Phone No. 0321-7821365. 3. Mr. Adeel Sattar, PARASITOLOGY S/o Abdul Sattar Zia, Chak No. 80 J.B. Tehsil & District Faisalabad. 3003 Phone No. 041-2557370. 4. Mr. Bilal Khalil, PARASITOLOGY S/o Dr. Khalil-ur-Rehman, House No. 4, Street No. 1, Block-W, Madina Town, Faisalabad. 3004 Phone No. 0321-6655927. 5. Hafiz Muhammad Hasham, PARASITOLOGY S/o Rana Shamim Ahmed, Room No. 25-C, Liaqat Hall, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. 3005 Phone No. 0345-6602057. 6. Hafiz Qadeer Ahmad, PARASITOLOGY S/o Naseer Ahmad, House No. P-52-C, Street No. 5, Mohallah Aslam Gunj, Tezab Mill Road, 3006 Faisalabad. Phone No. 041-8725367. 7. Mr. Ijaz Saleem, PARASITOLOGY S/o Muhammad Saleem, House No. P-68-A, Street No. 3, Mahmood Abad,Near Novelty Cinema, Faisalabad. 3007 Phone No. 041-2663590. 8. Mian Muhammad Awais, PARASITOLOGY S/o Ch. Abdul Ghani, House No. 697, Amin Town, B-Block, West Canal Road, Faisalabad. 3008 Phone No. 0332-4482304. 9. Mr. Muhammad Nadeem, PARASITOLOGY S/o Ghulam Nabi, House No. 22, Firdous Colony, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. 3009 Phone No. 0302-7121122. 10. Mr. Muhammad Qasir Shahzad, PARASITOLOGY 3010 S/o Muhammad Yousaf, House No. 109, Firdous Colony, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. Phone No.