Shocks, Groups, and Networks in Bukidnon, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study of Metro Manila

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Manasan, Rosario G.; Mercado, Ruben G. Working Paper Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 1999-03 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Manasan, Rosario G.; Mercado, Ruben G. (1999) : Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 1999-03, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/187389 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Governance and Urban Development: Case Study of Metro Manila Rosario G. -

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project

Community Management Plan July 2019 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project SAIA-Higaonon Tribal Council Inc. and Itoy Amosig Higaonon Tribal Community Inc. under Kalanawan Ancestral Domain Prepared by Higaonon community of Malitbog, Bukidnon for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Asian Development Bank i ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank ADSDPP - Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan AGMIHICU - Agtulawon Mintapod Higaonon Cumadon AFP - Armed Forces of the Philippines CADT - Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title CLUP - Community Land Use Plan CMP - Community Management Plan CP - Certificate of Pre-condition DepEd - Department of Education DENR - Department of Environment and Natural Resources DOH - Department of Health DTI - Department of Trade and Industry FGD - Focus Group Discussion FPIC - Free, Prior and Informed Consent GO - Government Organizations GRC - Gender Responsiveness Checklist IAHTCO - Itoy Amosig Higaonon Tribal Community Organization, Inc. ICC - Indigenous Cultural Communities IEC - Information, Education and Communication INREMP - Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project IP - Indigenous Peoples IPDF - Indigenous People’s Development Framework IPMR - Indigenous People Mandatory Representative IPO - Indigenous Peoples Organization IPP - Indigenous Peoples Plan IPRA - Indigenous Peoples Rights Act LGU - Local Government Unit M&E - Monitoring and Evaluation Masl - Meters above sea level MLGU - Municipal Local Government -

Part Ii Metro Manila and Its 200Km Radius Sphere

PART II METRO MANILA AND ITS 200KM RADIUS SPHERE CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA CHAPTER 7 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 7.1 PHYSICAL PROFILE The area defined by a sphere of 200 km radius from Metro Manila is bordered on the northern part by portions of Region I and II, and for its greater part, by Region III. Region III, also known as the reconfigured Central Luzon Region due to the inclusion of the province of Aurora, has the largest contiguous lowland area in the country. Its total land area of 1.8 million hectares is 6.1 percent of the total land area in the country. Of all the regions in the country, it is closest to Metro Manila. The southern part of the sphere is bound by the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon, all of which comprise Region IV-A, also known as CALABARZON. 7.1.1 Geomorphological Units The prevailing landforms in Central Luzon can be described as a large basin surrounded by mountain ranges on three sides. On its northern boundary, the Caraballo and Sierra Madre mountain ranges separate it from the provinces of Pangasinan and Nueva Vizcaya. In the eastern section, the Sierra Madre mountain range traverses the length of Aurora, Nueva Ecija and Bulacan. The Zambales mountains separates the central plains from the urban areas of Zambales at the western side. The region’s major drainage networks discharge to Lingayen Gulf in the northwest, Manila Bay in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the east, and the China Sea in the west. -

REGION 10 #Coopagainstcovid19

COOPERATIVES ALL OVER THE COUNTRY GOING THE EXTRA MILE TO SERVE THEIR MEMBERS AND COMMUNITIES AMIDST COVID-19 PANDEMIC: REPORTS FROM REGION 10 #CoopAgainstCOVID19 Region 10 Cooperatives Countervail COVID-19 Challenge CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY - The challenge of facing life with CoViD-19 continues. But this emergency revealed one thing: the power of cooperation exhibited by cooperatives proved equal if not stronger than the CoVID-19 virus. Cooperatives continued to show their compassion not just to ease the burden of fear of contracting the deadly and unseen virus, but also to ease the burden of hunger and thirst, and the burden of poverty and lack of daily sustenance. In Lanao del Norte, cooperatives continued to show their support by giving a second round of assistance through the Iligan City Cooperative Development Council (ICCDC), where they distributed food packs and relief goods to micro cooperatives namely: Lambaguhon Barinaut MPC of Brgy. San Roque, BS Modla MPC, and Women Survivors Marketing Cooperative. All of these cooperatives are from Iligan City. In the Province of Misamis Oriental, the spirit of cooperativism continues to shine through amidst this pandemic. The Fresh Fruit Homemakers Consumer Cooperative in Mahayahay, Medina, Misamis Oriental extended help by distributing relief food packages to their members and community. The First Jasaan Multi-Purpose Cooperative provided food assistance and distributed grocery items to different families affected by Covid 19 in Solana, Jasaan, Misamis Oriental. Meanwhile, the Misamis Oriental PNP Employees Multi- Purpose Cooperative initiated a gift-giving program to the poor families of San Martin, Villanueva, Misamis Oriental. Finally, the Mambajao Central School Teachers and Employees Cooperative (MACESTECO) in Mambajao, Camiguin distributed rice packs and relief items to their community. -

Mindanao-Pricelist-3Rd-Qtr-2020.Pdf

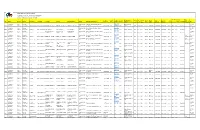

BANK OF COMMERCE ROPA PRICELIST - MINDANAO As of 3RD QTR, 2020 AREA INDICATIVE PROPERTY DESCRIPTION PROPERTY LOCATION TCT / CCT NO. STATUS (SQM) PRICE REGION IX - WESTERN MINDANAO ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR LAND WITH 1-STOREY LOT 1 BLK 3, JOHNSTON ST., BRGY. SAN JOSE GUSU (BRGY. BALIWASAN), T-223,208 820.00 5,063,000.00 RESIDENTIAL & OFFICE BLDG. ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DE SUR LOT 513, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,923 71,424.00 7,143,000.00 SUR LOT 514-B, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,924 12,997.00 1,300,000.00 DEL SUR LOT 509-B, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,925 20,854.00 2,086,000.00 DEL SUR LOT 512, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,926 11,308.00 1,131,000.00 SUR LOT 510, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,927 4,690.00 469,000.00 SUR LOT 511, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,928 17,008.00 1,701,000.00 SUR BLK 8, COUNTRY HOMES SUBD., BRGY. AYALA, ZAMBOANGA CITY (SITE IV), RESIDENTIAL VACANT LOT T-217,929 1,703.00 1,022,000.00 ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR BLK 9, COUNTRY HOMES SUBD., BRGY. AYALA, ZAMBOANGA CITY (SITE IV), RESIDENTIAL VACANT LOT T-217,930 1,258.00 755,000.00 ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR BLK 11, COUNTRY HOMES SUBD., BRGY. -

NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO.: X- NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries - CY 2020 Other Plant Locations Status Mine Site Mine Mine Site E- Head Office Head Office Head Office E- Head Office Mine Site Mailing Type of Permit Date Date of Area municipality, Non- Telephon Site Fax mail barangay Year Region Mineral Province Municipality Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Head Office Mailing Address Telephone No. Fax No. mail Address Website (hectares) province Producing TIN Address e No. No. Address Permit Number Approved Expiration Producing donjieanim 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Poblacion, Sapang Dalaga, Misamis as@yahoo Dioyo, Sapang 191-223- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Sapang Dalaga Sand and Gravel ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ager Occidental 9654955493 N/A .com N/A Dalaga N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-07-19 11/10/2019 10/10/2020 1.00 N/A N/A Producing 205 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man South Western, Calamba, Misamis ljcyap7@g 432-503- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. ager Occidental 9466875752 N/A mail.com N/A Sulipat, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-18-19 04/02/2020 03/02/2021 1.9524 N/A N/A Producing 363 maconsuel 10-Northern Non- Misamis ROGELIO, MARIA ROGELIO, MA. ROGELIO, MA. Proprietor/Man Northern Poblacion, Calamba, Misamis orogelio@ 325-550- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel CONSUELO A. CONSUELO A. CONSUELO ager Occidental 9464997271 N/A gmail.com N/A Solinog, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-03-20 24/06/2020 23/06/2021 1.094 N/A N/A Producing 921 noel_pagu 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Southern Poblacion, Plaridel, Misamis e@yahoo. -

RA No. 11565: First Misamis Oriental General Hospital

•I No. 6753 be char^ed against the current year’s appropriations of the Medina Extension Hospital, the amount of Nine hundred ^spuHIit of fIjB ^ijilipjrincs million pesos (P900,000,000.00) is hereby appropriated for the implementation of this Act which shall be included and funded Congress nfflfe pijtltgptnes ^der the 2022 General Appropriations Act under the Health Facilities Enhancement Program (HFEP) of the DOH. Therea^r, such sums as may be necessary for its continued Jigljfgcnflj Soogreas operation shall be included in the annual General Appropriations Act. i3ecoHh ^gular<^£ssdn« Sec. 3. The Secretary of Health shall prepare and issue e necessary rules andregulations for the effective implementation ot this Act consistent with the hospital development plan. Begun and held in Metro Manila, on Monday, the twenty-seventh Sec. 4. This Act shall take effect fifteen (15) days aft/i day of July, two thousand twenty. Its pubhcation in the Official Gazette or in a newspaper of general circulation. proved. [Republic act no. 11565] A.N ACT CONVERTING THE MEDINA EXTENSION VICENTE C. om LORD ALL. Q. VELASCO HOSPITAL IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF MEDINA, President of i enate 2 House PROVINCE OF MISAMIS ORIENTAL INTO A of Representatives GENERAL HOSPITAL TO BE KNOWN AS THE FIRST MISAMIS ORIENTAL GENERAL HOSPITAL This Act which originated in the House of Representatives AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR was p^sed by the House of Representatives on June 3, 2020 amended by the Senate of the Philippines on May 31,2021, and Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the which amendment was concurred in by the House of Philippines in Congress assembled: Representatives on Jime 2,2021. -

Binanog Dance

Gluck Classroom Fellow: Jemuel Jr. Barrera-Garcia Ph.D. Student in Critical Dance Studies: Designated Emphasis in Southeast Asian Studies Flying Without Wings: The Philippines’ Binanog Dance Binanog is an indigenous dance from the Philippines that features the movement of an eagle/hawk to the symbolic beating of bamboo and gong that synchronizes the pulsating movements of the feet and the hands of the lead and follow dancers. This specific type of Binanog dance comes from the Panay-Bukidnon indigenous community in Panay Island, Western Visayas, Philippines. The Panay Bukidnon, also known as Suludnon, Tumandok or Panayanon Sulud is usually the identified indigenous group associated with the region and whose territory cover the mountains connecting the provinces of Iloilo, Capiz and Aklan in the island of Panay, one of the main Visayan islands of the Philippines. Aside from the Aetas living in Aklan and Capiz, this indigenous group is known to be the only ethnic Visayan language-speaking community in Western Visayas. SMILE. A pair of Binanog dancers take a pose They were once associated culturally as speakers after a performance in a public space. of the island’s languages namely Kinaray-a, Akeanon and Hiligaynon, most speakers of which reside in the lowlands of Panay and their geographical remoteness from Spanish conquest, the US invasion of the country, and the hairline exposure they had with the Japanese attacks resulted in a continuation of a pre-Hispanic culture and tradition. The Suludnon is believed to have descended from the migrating Indonesians coming from Mainland Asia. The women have developed a passion for beauty wearing jewelry made from Spanish coins strung together called biningkit, a waistband of coins called a wakus, and a headdress of coins known as a pundong. -

Madweng Pottery Tradition in Santa Maria, Isabela Raquel R

IRCHE 2017 4th International Research Conference on Higher Education Volume 2018 Conference Paper Madweng Pottery Tradition in Santa Maria, Isabela Raquel R. Geronimo Philippine Normal University North Luzon Abstract This study investigates the unique indigenous pottery traditions of the Madweng in an Ibanag community in Santa, Maria, Isabela, located in the interior northwestern part of the province of Isabela, Philippines which boasts its huge non -metallic deposit of clay. The Madweng are the Ibanag potters who make, produce such earthenwares. Ethnography as a research design and strategy is utilized to understand indigenous concepts, technology and pottery traditions in manufacturing the dweng. Ethnographic methods like interviews, fieldwork, recording of field notes, direct observation, and Corresponding Author: smartphones were used for photographs, audio recording and analyzing data. Utilizing Raquel R. Geronimo mga katutubong metodo sa Sikolohiyang Pilipino (methods in Filipino Psychology) [email protected] the indigenous method of pakikipagkuwentuhan” (sharing stories), and pagtatanong- Received: 23 April 2018 tanong (asking around), the Ibanag language was employed to draw information Accepted: 8 May 2018 Published: 4 June 2018 in the indigenous idea of pagpapakuwento” (someone is telling the story). Results showed that Ibanag pottery tradition was introduced by the Kalingas, kept and Publishing services provided by Knowledge E used as a significant part of an Ibanag heritage from their ancestors. Manu-mano or hand modelling, maffulang or painting, magabba or firing, were some parts of Raquel R. Geronimo. This article is distributed under the indigenizing methods by the Madweng. Since 1954, no major changes in the method terms of the Creative Commons of manufacture from the teachings of the Kalingas except for a minimal technological Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and advancement in manufacturing pots using the hurmaan, or molder. -

Obsidian Sourcing at Ulilang Bundok Site and Its Implications for Mobility, Exchange, and Social Contexts in the Philippine Metal Age

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Obsidian Sourcing at Ulilang Bundok Site and its Implications for Mobility, Exchange, and Social Contexts in the Philippine Metal Age STEPHEN CHIA, LEEE ANTHONY M. NERI, AND AMALIA DE LA TORRE introduction What is commonly known as the “Metal Age” of the Philippines and throughout Island Southeast Asia is viewed as a critical period of transition between small-scale Neolithic farming communities of the third millennium to early first millenniumb.c. and the historically recorded emergence of centralized polities with archaeological evidence for social complexity and trade networks involving exotic goods stretching into mainland Asia and beyond by the late first millenniuma.d. (Andrews and Glover 1986; Bronson 1992; Bulbeck 2007; Bulbeck and Prasetyo 2000; Lloyd-Smith and Cole 2010). Much of the archaeological work on this time period in the Philippines has focused on burial sites, including often spectacularly artistic jar burials (often with anthropomorphic features) and inhumation burials with regional stylistic embellish- ments ( Dizon 1979; Dizon and Santiago 1996; Dizon et al. 2011; Fox and Evange- lista 1957; Kurjack et al. 1971; Tenazas 1974). These varying types of elaborate burials are typically accompanied by elaborately embellished rare or exotic goods such as nephrite or jade ornaments, bronze ornaments and implements, and glass beads (al- most certainly traded from outside the archipelago), as well as highly decorated earth- enware forms, gold-leaf ornaments, iron objects, rare shells, polished stone adzes, and obsidian (which could have been either extracted and modified within the Philippine archipelago or obtained from long-distance sources). -

MAKING the LINK in the PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment

MAKING THE LINK IN THE PHILIPPINES Population, Health, and the Environment The interconnected problems related to population, are also disappearing as a result of the loss of the country’s health, and the environment are among the Philippines’ forests and the destruction of its coral reefs. Although greatest challenges in achieving national development gross national income per capita is higher than the aver- goals. Although the Philippines has abundant natural age in the region, around one-quarter of Philippine fami- resources, these resources are compromised by a number lies live below the poverty threshold, reflecting broad social of factors, including population pressures and poverty. The inequity and other social challenges. result: Public health, well-being and sustainable develop- This wallchart provides information and data on crit- ment are at risk. Cities are becoming more crowded and ical population, health, and environmental issues in the polluted, and the reliability of food and water supplies is Philippines. Examining these data, understanding their more uncertain than a generation ago. The productivity of interactions, and designing strategies that take into the country’s agricultural lands and fisheries is declining account these relationships can help to improve people’s as these areas become increasingly degraded and pushed lives while preserving the natural resource base that pro- beyond their production capacity. Plant and animal species vides for their livelihood and health. Population Reference Bureau 1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 520 Washington, DC 20009 USA Mangroves Help Sustain Human Vulnerability Coastal Communities to Natural Hazards Comprising more than 7,000 islands, the Philippines has an extensive coastline that is a is Increasing critical environmental and economic resource for the nation. -

Small Odonata Collection from Talaingod, Davao Del Northe

International Dragonfly Fund - Report Journal of the International Dragonfly Fund ISSN 1435-3393 Content Villanueva, Reagan J.T. & Hilario Cahilog Small Odonata collection from Talaingod, Davao del Norte, Mindanao Island, Philippines 1-26 Volume 59 2013 The International Dragonfly Fund (IDF) is a scientific society founded in 1996 for the improvement of odonatological knowledge and the protection of species. Internet: http://www.dragonflyfund.org/ This series intends to publish studies promoted by IDF and to facilitate cost-efficient and rapid dis- semination of odonatological data. Editorial Work: Martin Schorr Layout: Martin Schorr Indexed by Zoological Record, Thomson Reuters, UK Home page of IDF: Holger Hunger Printing: ikt Trier, Germany Impressum: International Dragonfly Fund - Report - Volume 59 Date of publication: 09.02.2013 Publisher: International Dragonfly Fund e.V., Schulstr. 7B, 54314 Zerf, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Responsible editor: Martin Schorr International Dragonfly Fund - Report 59 (2013): 1-26 1 Small Odonata collection from Talaingod, Davao del Norte, Mindanao Island, Philippines R.J.T. Villanueva1 & H. Cahilog2 1D3C Gahol Apartment, Lopez Jaena St., Davao City, 8000 Philippines [email protected] 2La Union, San Isidro, Davao Oriental, 8209 Philippines Abstract Odonata survey was conducted in Talaingod, Davao del Norte, Mindanao Island. Four major sites were explored in Barangay Santo Niño from December 26 – 30, 2012. Thirty five species under eleven families including one new species were found re- presenting the first odonatological record in the province of Davao del Norte. Three species need further study while Orthetrum glaucum represents a new record for the island of Mindanao. Coeliccia exoleta population, a vulnerable species in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, was found.