FREE Volume VIII Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unrevised Hansard Mini-Plenary National

UNREVISED HANSARD MINI-PLENARY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THURSDAY, 27 FEBRUARY 2020 Page: 1 THURSDAY, 27 FEBRUARY 2020 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE MINI-PLENARY – NATIONAL ASSEMBLY CHAMBER ____ Members of the mini-plenary met in the Chamber of the National Assembly at 14:01. The Deputy Speaker, as the Chairperson, took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayer or meditation. TRANSFORMING SOCIETY AND UNITING THE COUNTY BY CULTIVATING A SHARED RECOMMITMENT TO CONSTITUTIONAL VALUES THAT PROMOTE NATION-BUILDING, STRENGTHEN SOCIAL COHESION AND IMPROVE THE QUALITY OF LIFE FOR ALL SOUTH AFRICANS (Subject for Discussion) Dr N P NKABANE: Deputy Speaker, hon members in the House, guests and the broader society, in particular, those segments in our communities that are watching this debate today, we UNREVISED HANSARD MINI-PLENARY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THURSDAY, 27 FEBRUARY 2020 Page: 2 wish to reaffirm our commitment to the ANC’s manifesto for the 2019 general elections which is “Let’s grow South Africa together”. It is our responsibility as the ANC-led government to reprogram the subconscious mind by providing it with consistent messaging that aligns with the progressive programme that we seek to achieve. Nelson Mandela once said: “fools multiply when wise men are silent.” The President of the Republic of South Africa, His Excellency Mr Cyril Ramaphosa reiterated that and I quote: “the freedom we enjoy today was achieved through struggle, determination and great sacrifice”. He further reiterated that and I quote: “despite the challenges and setbacks, we won our freedom by working together and never giving up.” House Chairperson, it is well known that the postapartheid state of constitutional democracy was faced with a broad spectrum of political, socioeconomic and human rights issues aimed at challenging the status core of the state that was more of a racially exclusive capitalist that benefited my people on the left; where black people who constituted the majority were excluded from the social, political and economic realms of the dominant society. -

South Africa's Anti-Corruption Bodies

Protecting the public or politically compromised? South Africa’s anti-corruption bodies Judith February The National Prosecuting Authority and the Public Protector were intended to operate in the interests of the law and good governance but have they, in fact, fulfilled this role? This report examines how the two institutions have operated in the country’s politically charged environment. With South Africa’s president given the authority to appoint key personnel, and with a political drive to do so, the two bodies have at times become embroiled in political intrigues and have been beholden to political interests. SOUTHERN AFRICA REPORT 31 | OCTOBER 2019 Key findings Historically, the National Prosecuting Authority The Public Protector’s office has fared (NPA) has had a tumultuous existence. somewhat better overall but its success The impulse to submit such an institution to ultimately depends on the calibre of the political control is strong. individual at its head. Its design – particularly the appointment Overall, the knock-on effect of process – makes this possible but might not in compromised political independence is itself have been a fatal flaw. that it is felt not only in the relationship between these institutions and outside Various presidents have seen the NPA and Public Protector as subordinate to forces, but within the institutions themselves and, as a result, have chosen themselves. leaders that they believe they could control to The Public Protector is currently the detriment of the institution. experiencing a crisis of public confidence. The selection of people with strong and This is because various courts, including visible political alignments made the danger of the Constitutional Court have found that politically inspired action almost inevitable. -

Powers of the Public Protector: Are Its Findings and Recommendations Legally Binding?

POWERS OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR: ARE ITS FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS LEGALLY BINDING? by MOLEFHI SOLOMON PHOREGO 27312837 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Laws (LLM Research): Public Law Study Leader: Professor Danie Brand Department of Public Law, University of Pretoria November 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………….........................vii CHAPTER 1 Introduction…..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 The Public Protector as a Chapter Nine Institution………………………………………………………1 Research problem………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Aims and objectives of study……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Research Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Research Questions………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 Limitations…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter Outline……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 CHAPTER 2 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS GOVERNING THE OPERATIONS OF THE OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 The Constitutional provisions……………………………………………………………………………………..7 Meaning of “Appropriate remedial action’ as contained in the Constitution….…………..11 STATUTORY PROVISIONS REGULATING THE OFFICE OF THE PUBLIC PROTECTOR……...10 Section 6 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….12 i Section 7 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….17 Section 8 of the Public Protector Act………………………………………………………………………….19 -

African National Congress NATIONAL to NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob

African National Congress NATIONAL TO NATIONAL LIST 1. ZUMA Jacob Gedleyihlekisa 2. MOTLANTHE Kgalema Petrus 3. MBETE Baleka 4. MANUEL Trevor Andrew 5. MANDELA Nomzamo Winfred 6. DLAMINI-ZUMA Nkosazana 7. RADEBE Jeffery Thamsanqa 8. SISULU Lindiwe Noceba 9. NZIMANDE Bonginkosi Emmanuel 10. PANDOR Grace Naledi Mandisa 11. MBALULA Fikile April 12. NQAKULA Nosiviwe Noluthando 13. SKWEYIYA Zola Sidney Themba 14. ROUTLEDGE Nozizwe Charlotte 15. MTHETHWA Nkosinathi 16. DLAMINI Bathabile Olive 17. JORDAN Zweledinga Pallo 18. MOTSHEKGA Matsie Angelina 19. GIGABA Knowledge Malusi Nkanyezi 20. HOGAN Barbara Anne 21. SHICEKA Sicelo 22. MFEKETO Nomaindiya Cathleen 23. MAKHENKESI Makhenkesi Arnold 24. TSHABALALA- MSIMANG Mantombazana Edmie 25. RAMATHLODI Ngoako Abel 26. MABUDAFHASI Thizwilondi Rejoyce 27. GODOGWANA Enoch 28. HENDRICKS Lindiwe 29. CHARLES Nqakula 30. SHABANGU Susan 31. SEXWALE Tokyo Mosima Gabriel 32. XINGWANA Lulama Marytheresa 33. NYANDA Siphiwe 34. SONJICA Buyelwa Patience 35. NDEBELE Joel Sibusiso 36. YENGENI Lumka Elizabeth 37. CRONIN Jeremy Patrick 38. NKOANA- MASHABANE Maite Emily 39. SISULU Max Vuyisile 40. VAN DER MERWE Susan Comber 41. HOLOMISA Sango Patekile 42. PETERS Elizabeth Dipuo 43. MOTSHEKGA Mathole Serofo 44. ZULU Lindiwe Daphne 45. CHABANE Ohm Collins 46. SIBIYA Noluthando Agatha 47. HANEKOM Derek Andre` 48. BOGOPANE-ZULU Hendrietta Ipeleng 49. MPAHLWA Mandisi Bongani Mabuto 50. TOBIAS Thandi Vivian 51. MOTSOALEDI Pakishe Aaron 52. MOLEWA Bomo Edana Edith 53. PHAAHLA Matume Joseph 54. PULE Dina Deliwe 55. MDLADLANA Membathisi Mphumzi Shepherd 56. DLULANE Beauty Nomvuzo 57. MANAMELA Kgwaridi Buti 58. MOLOI-MOROPA Joyce Clementine 59. EBRAHIM Ebrahim Ismail 60. MAHLANGU-NKABINDE Gwendoline Lindiwe 61. NJIKELANA Sisa James 62. HAJAIJ Fatima 63. -

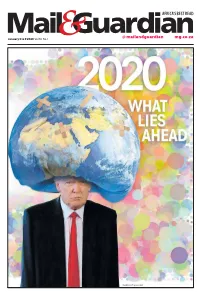

Africa's Best Read

AFRICA’S BEST READ January 3 to 9 2020 Vol 36 No 1 @ mailandguardian mg.co.za Illustration: Francois Smit 2 Mail & Guardian January 3 to 9 2020 Act or witness IN BRIEF – THE NEWS YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED Time called on Zulu king’s trust civilisation’s fall The end appears to be nigh for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls more than three million A decade ago, it seemed that the climate hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf crisis was something to be talked about of King Goodwill Zwelithini, after the govern- in the future tense: a problem for the next ment announced it will accept the recommen- generation. dations of the presidential high-level panel on The science was settled on what was land reform to review the trust’s operations or causing the world to heat — human emis- repeal the legislation. sions of greenhouse gases. That impact Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and had also been largely sketched out. More Rural Development Thoko Didiza announced heat, less predictable rain and a collapse the decision to accept the recommendations in the ecosystems that support life and and deal with barriers to land ownership human activities such as agriculture. on land controlled by amakhosi as part of a But politicians had failed to join the dots package of reforms concerned with rural land and take action. In 2009, international cli- tenure. mate negotiations in Copenhagen failed. She said rural land tenure was an “immedi- Other events regarded as more important ate” challenge which “must be addressed.” were happening. -

Advocate Busisiwe Mkhwebane Public Protector in the Public’S Perception? Report on the Public Protector’S First 100 Days in Office

ADVOCATE BUSISIWE MKHWEBANE PUBLIC PROTECTOR IN THE Public’s PERCEPTION? Report on the Public Protector’s first 100 days in office 17/10/2016 - 24/01/2017 COMPILED BY AFRIFORUM Report on the Public Protector’s first 100 days in office Report TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 4 Legal basis 5 CV Adv. Busisiwe Mkhwebane 6 Objections by Opposition & Appointment 8 Media Statements & Reports – Timeline 8 Conclusion 13 3 Report Report on the Public Protector’s first 100 days in office INTRODUCTION The office of the Public Protector (PP) was created by the President would eventually approve the appointment. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 as one of the instruments to create checks and balances and limit From a shortlist of 14 candidates, which included Judge the power of Parliament and the Government. The PP and Sharise Weiner, Judge Sirajudien Desai, Adv. Kevin Malunga, other Chapter 9 institutions were heavily debated during Adv. Nonkosi Cetywayo, Adv. Mhlaliseni Mthembu, Adv. the discussions around the adoption of the Constitution. Madibeng Mokoditwa, Adv. Mamiki Goodman, Prof. Narnia Their eventual inclusion in the Constitution was therefore a Bohler-Muller, Prof Bongani Majola, Ms Jill Oliphant, Ms victory for the South African people, although the first public Muvhango Lukhaimane, Ms Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, and protectors were relatively unknown and they were often Mr Willie Hofmeyr, Ms Busisiwe Mkhwebane eventually criticised for not performing their constitutional duties. emerged victorious, if one can call it that, and was appointed as the new Public Protector. With Thuli Madonsela transforming the office of the Public Protector from a rather unknown and almost insignificant This report aims to evaluate the new Public Protector’s state institution to virtual rock star status in South Africa first 100 days in office, starting from her first day at the through her handling of the Nkandla case and her state office on 17 October 2016. -

Statement by Public Protector Adv. Busisiwe Mkhwebane

Statement by Public Protector Adv. Busisiwe Mkhwebane during a meeting of the Portfolio Committee on Justice and Correctional Services on Tuesday, March 06, 2018 in Parliament, Cape Town. Honourable Chairperson, Dr. Mathole Motshekga; Honourable Members of the Committee; Ladies and gentlemen; Good morning! I appreciate the opportunity to appear before the Committee to offer the much needed clarity on matters that appear to have given rise to a sense of disquiet among Honourable Members and the public at large. In the same breath, I am grateful that this opportunity provides a platform for me to bring to the attention of the Committee a worrying state of affairs in my office that is threatening to hamper the delivery of services to the people of South Africa. The latter statement refers to conditions that have a potential to pose a serious threat to the realization of the vision that underpins all of my office’s operations. That is Vision 2023, an elaborate eight-pillared blueprint whose main thrust is to see to it that the services of this institution make a greater impact at the grassroots than ever before. I will come back to this point shortly. Honourable Chairperson and Members, my constitutional mandate aside, one of the things I undertook to put high-up on my priority list right at the beginning of my term of office was forging and nurturing mutually beneficial relations between my office and stakeholders. This was informed by the understanding that, although it is independent, my office is not an island. Its successes and failures depend on how strong the links are 1 between us and those that have a keen interest in the ever so important task entrusted to us. -

Sonaparliament

MAKING YOUR FUTURE WORK BETTER – Learning from Madiba and Ma Sisulu The official Magazine of the Parliament of the Republic of South Africa PRE-SONA EDITION 2019 Parliament: Following up on our commitments SONA to the people Contents Vision an activist and responsive people’s Parliament that improves the quality of life of South africans and ensures enduring equality in our society. mission Parliament aims to provide a service to the people of South Africa by providing the following: • A vibrant people’s Assembly that intervenes and transforms society and addresses the development challenges of our people; • Effective oversight over the Executive by strengthening its scrutiny of actions against the needs of South Africans; Provinces of Council National of od • Participation of South Africans in the decision-making r of National Assembly National of processes that affect their lives; Black ace ace • A healthy relationship between the three arms of the State, that promotes efficient co-operative governance between the spheres of government, and ensures appropriate links M with our region and the world; and • An innovative, transformative, effective and efficient parliamentary service and administration that enables Members of Parliament to fulfil their constitutional responsibilities. Strategic Objectives 1. Strengthening oversight and accountability 2. enhancing public involvement 3. Deepening engagement in international fora 4. Strengthening co-operative government 5. Strengthening legislative capacity Contents CONteNtS 5 6 7 12 14 5. Presiding Officers of Parliament 6. The significance of the State of the Nation Address 7. SONA brings together the three arms of State 12. Public Participation in a people’s Parliament 14. -

Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 60 Issue 1 Twenty Years of South African Constitutionalism: Constitutional Rights, Article 7 Judicial Independence and the Transition to Democracy January 2016 Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector TSELISO THIPANYANE Chief Executive Officer at the Safer South Africa Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation TSELISO THIPANYANE, Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector, 60 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2015-2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Tseliso Thipanyane Strengthening Constitutional Democracy: Progress and Challenges of the South African Human Rights Commission and Public Protector 60 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 125 (2015–2016) ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Tseliso Thipanyane is the Chief Executive Officer at the Safer South Africa Foundation; an independent consultant on human rights, democracy, and good governance; former adjunct Lecturer-in-Law at Columbia Law School; and former Chief Executive Officer of the South African Human Rights Commission. www.nylslawreview.com 125 STRENGTHENING CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 60 | 2015/16 Human rights and fundamental freedoms are the birthright of all human beings; their protection and promotion is the first responsibility of Governments.1 I. -

Progress and Pitfalls in South Africaâ•Žs Socio-Economic Jurisprudence

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2014 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2014 The “Reasonableness” of Poverty: Progress and Pitfalls in South Africa’s Socio-economic Jurisprudence Benajmin Oliver Powers Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2014 Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Powers, Benajmin Oliver, "The “Reasonableness” of Poverty: Progress and Pitfalls in South Africa’s Socio- economic Jurisprudence" (2014). Senior Projects Spring 2014. 3. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2014/3 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The “Reasonableness” of Poverty: Progress and Pitfalls in South Africa’s Socio-economic Jurisprudence Senior Project submitted to The Division of Social Studies and Interdivisional Programs Of Bard College By Benjamin Powers Annandale on Hudson, New York May 2014 1 2 I would like to thank my advisor Peter Rosenblum, for constantly unsettling my thoughts during this project, and questioning me at every turn. -

The Public Protector As a Mechanism of Political Accountability

The Public Protector as a Mechanism of Political Accountability:CJ TCHAWOUO The Extent MBIADA of its ContributionPER / PELJ 2017 (20) 1 to the Realisation of the Right to Access Adequate Housing in South Africa CJ Tchawouo Mbiada* Abstract Pioneer in peer -reviewed, open access online law publications This paper is premised on the concept of political accountability which aims to hold accountable government for its action and or Author omission. Political accountability encompasses a number of mechanisms such as the judiciary and the ombudsman. Courts Carlos Joel Tchawouo Mbiada have been instrumental in enforcing the realisation of the right to access to adequate housing in South Africa. This paper argues, Affiliation however, that the judiciary is not the only enforcing avenue because other mechanisms of political accountability may also Labour Appeal Court, South Africa contribute to the realisation of the right to housing. The paper, therefore, explores the extent of the Public Protector's Email [email protected] contribution to the realisation of the right to access to adequate Date published housing. The paper then argues that it is through its functions that the Public Protector exercises its accounting role in the 28 May 2017 realisation of the right to access to adequate housing. The paper, however, cautions that the Public Protector is not an alternative Editor Prof C Rautenbach dispute resolution institution parallel to courts. But that the Public Protector complements the role played by courts by offering How to cite this article another medium through which such right may be realised. Tchawouo Mbiada CJ "The Public Protector as a Mechanism of Political Accountability: The Extent of its Contribution to the Realisation Keywords of the Right to Access Adequate Housing in South Africa" PER / Right to access to adequate housing; political accountability; PELJ 2017(20) - DOI judiciary; ombudsman; Public Protector; accountability; http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727- 3781/2017/v20n0i1382 enforcement and realisation. -

Electoral Act: National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures

4 No. 42460 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 MAY 2019 GENERAL NOTICE GENERAL NOTICES • ALG EMENE KENNISGEWINGS NOTICEElectoral Commission/….. Verkiesingskommissie OF 2019 ELECTORAL COMMISSION ELECTORALNOTICE 267 COMMISSION OF 2019 267 Electoral Act (73/1998): List of Representatives in the National Assembly and Provincial Legislatures, in respect of the elections held on 8 May 2019 42460 ELECTORAL ACT, 1998 (ACT 73 OF 1998) PUBLICATION OF LISTS OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY AND PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES IN TERMS OF ITEM 16 (4) OF SCHEDULE 1A OF THE ELECTORAL ACT, 1998, IN RESPECT OF THE ELECTIONS HELD ON 08 MAY 2019. The Electoral Commission hereby gives notice in terms of item 16 (4) of Schedule 1A of the Electoral Act, 1998 (Act 73 of 1998) that the persons whose names appear on the lists in the Schedule hereto have been elected in the 2019 national and provincial elections as representatives to serve in the National Assembly and the Provincial Legislatures as indicated in the Schedule. SCHEDULE This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za NATIONAL ASSEMBLY LIST Party List Rank ID Name Surname AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 1 5401185719080 KENNETH RASELABE JOSEPH MESHOE AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 2 5902085102087 STEVEN NICHOLAS SWART AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY National 3 6302015139086 WAYNE MAXIM THRING AFRICAN CHRISTIAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY Regional: Western Cape 1 7206180506087 MARIE ELIZABETH SUKERS AFRICAN INDEPENDENT CONGRESS National 1 6207056007086 MANDLENKOSI PHILLIP GALO