00-RCN20 [Output]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPARTMENT of HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION 9 Physics

No. EX II (2)/00001/HSE/2017 DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM - MARCH 2017 LIST OF EXTERNAL EXAMINERS (Centre wise) 9 Physics District: Pathanamthitta Sl.No School Name External Examiner External's School No. Of Batches 1 03001 : GOVT. BHSS, ADOOR, BEENA G 03031 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N V HSS, ANGADICAL SOUTH, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04734285751, 9447117229 <=15 2 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, MANJU.V.L 03041 8 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Junior (Physics) K.R.P.M. HSS, SEETHATHODE, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9495764711 <=15 3 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, THOMAS CHACKO 03010 4 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT BOYS Ph: Ph: , 9446100754 HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA,PATH ANAMTHITTA 30 4 03003 : GOVT. HSS, BIJU PHILIP 03050 6 EZHUMATTOOR, HSST Senior (Physics) TECHNICAL HSS, MALLAPPALLY EAST.P.O, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: 04812401131, 9447414839 10 Ph: PATHANAMTHITTA, 689584 5 03004 : GOVT.HSS, SHEEBA VARGHESE 03045 7 KADAMMANITTA, HSST Senior (Physics) MT HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: , 9447223589 10 Ph: 6 03005 : K annasa Smaraka GOVT HSS, JESSAN VARUGHESE 03016 8 KADAPRA, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) M G M HSS, THIRUVALLA, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04692702200, 9496212211 10 7 03006 : GOVT HSS, KALANJOOR, LEKSHMI.P.S 03009 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT HSS KONNI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9447086029 14 8 03007 : GOVT HSS, VECHOOCHIRA RAJIMOL P R 03026 4 COLONY, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N D P HSS, VENKURINJI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04735266367, 9495554912 <=15 9 03008 : GOVT -

TWO FORMS of "BE" in MALAYALAM1 Tara Mohanan and K.P

TWO FORMS OF "BE" IN MALAYALAM1 Tara Mohanan and K.P. Mohanan National University of Singapore 1. INTRODUCTION Malayalam has two verbs, uNTE and aaNE, recognized in the literature as copulas (Asher 1968, Variar 1979, Asher and Kumari 1997, among others). There is among speakers of Malayalam a clear, intuitively perceived meaning difference between the verbs. One strong intuition is that uNTE and aaNE correspond to the English verbs "have" and "be"; another is that they should be viewed as the "existential" and "equative" copulas respectively.2 However, in a large number of contexts, these verbs appear to be interchangeable. This has thwarted the efforts of a clear characterization of the meanings of the two verbs. In this paper, we will explore a variety of syntactic and semantic environments that shed light on the differences between the constructions with aaNE and uNTE. On the basis of the asymmetries we lay out, we will re-affirm the intuition that aaNE and uNTE are indeed equative and existential copulas respectively, with aaNE signaling the meaning of “x is an element/subset of y" and uNTE signaling the meaning of existence of an abstract or concrete entity in the fields of location or possession. We will show that when aaNE is interchangable with uNTE in existential clauses, its function is that of a cleft marker, with the existential meaning expressed independently by the case markers on the nouns. Central to our exploration of the two copulas is the discovery of four types of existential clauses in Malayalam, namely: Neutral: with the existential verb uNTE. -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO An Experimental Approach to Variation and Variability in Constituent Order A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Savithry Namboodiripad Committee in charge: Professor Grant Goodall, Chair Professor Farrell Ackerman Professor Victor Ferreira Professor Robert Kluender Professor John Moore 2017 Copyright Savithry Namboodiripad, 2017 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Savithry Namboodiripad is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on micro- film and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION iv EPIGRAPH (1) kaïãu: ña:n si:t”e: saw I Sita.ACC VERB SUBJECT OBJECT ‘I saw Sita’ Hanuman to Raman, needing to emphasize that he saw Sita The Ramayana (Malayalam translation) “borrowing (or diffusion, or calquing) of grammar in language contact is not a unitary mechanism of language change. Rather, it is a condition – or an externally motivated situation – under which the above three mechanisms [reanalysis, reinterpretation (or extension) and grammaticalization] can apply in an orderly and systematic way. The status of categories in the languages in contact is what determines the choice of a mechanism [...]”. Aikhenvald (2003) v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page................................... iii Dedication...................................... iv Epigraph.......................................v Table of Contents.................................. vi List of Figures................................... -

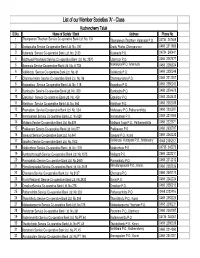

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. -

P R O V I S I O N a L

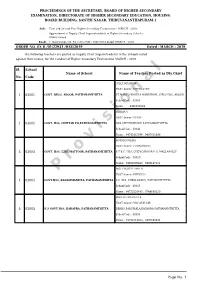

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECRETARY, BOARD OF HIGHER SECONDARY EXAMINATION, DIRECTORATE OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION, HOUSING BOARD BUILDING, SANTHI NAGAR, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM-1 Sub: First and Second Year Higher Secondary Examination - MARCH - 2019- Appointment of Deputy Chief Superintendents in Higher Secondary Schools - Orders Issued. Read:- 1. Notification No. EX II /01/22931 /HSE/2019 dated: MARCH - 2019 ORDER NO. EX II /01/22931 /HSE/2019 Dated : MARCH - 2019 The following teachers are posted as Deputy Chief Superintendents in the Schools noted against their names, for the Conduct of Higher Secondary Examination MARCH - 2019 Sl. School Name of School Name of Teacher Posted as Dty.Chief No. Code JOLLY MATHEW HSST Senior (CHEMISTRY) 1 03001 GOVT. BHSS, ADOOR, PATHANAMTHITTA ST.MARY'S MAHILA MANDIRAM, GIRLS HSS, ADOOR SchoolCode : 03083 Phone : -- , 9495266024 SREEJA V HSST Senior (HINDI) 2 03002 GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR PO,PATHANAMTHITTA HSS,SEETHATHODE,PATHANAMTHITTA SchoolCode : 03041 Phone : 04742415066 , 9497812999 ROSMI JOSEPH HSST Senior (ECONOMICS) 3 03003 GOVT. HSS, EZHUMATTOOR, PATHANAMTHITTA S T B C HSS, CHENGAROOR P O, MALLAPALLY, SchoolCode : 03020 Phone : 04692696482 , 9496147181 P r o v i s MOLLYKUTTYi o PHILIPn a l HSST Senior (PHYSICS) 4 03004 GOVT.HSS, KADAMMANITTA, PATHANAMTHITTA S C HSS, CHELLAKADU, PATHANMTHITTA SchoolCode : 03025 Phone : 04735226885 , 9744690150 SREELETHA DEVI S HSST Senior (MALAYALAM) 5 03005 K S GOVT HSS, KADAPRA, PATHANAMTHITTA DBHSS,PARUMALA,KADAPRA,PATHANAMTHITTA SchoolCode : 03035 Phone : 04792314822 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 25.04.2021To01.05.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 25.04.2021to01.05.2021 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 566/2021 CHARUMPARAPU U/s 4(2)(c) THEN VEEDU r/w 3(b) of PATHANA ASHKAR.M 01-05-2021 JAMALUDH 20, KOKKATHODE Kerala MTHITTA MADHU.C SI BAILED BY 1 JAMALUDH ABAN at 13:05 EEN Male P.O Epidemic (Pathanamth OF POLICE POLICE EEN Hrs ARUVAPPULAM Diseases itta) KONNI Ordinance 2020 566/2021 U/s 4(2)(c) EZHUTHIPPARA r/w 3(b) of PATHANA 01-05-2021 SHIYAS 20, VEEDU Kerala MTHITTA MADHU.C SI BAILED BY 2 AYAN ABAN at 13:10 KHAN Male PATHANAMTHITT Epidemic (Pathanamth OF POLICE POLICE Hrs A Diseases itta) Ordinance 2020 BIJU VARGHES 563/2021 S/O VARGHES U/s 4(2)(e)(j) VELLAPLACKAL PATHANA 01-05-2021 of Kerala BIJU 46, (H) KALEEKKAP MTHITTA SUNNY SI BAILED BY 3 VARGHES at 11:35 Epidemic VARGHES Male KALEEKKAPDI ADI (Pathanamth OF POLICE POLICE Hrs Diseases ,KUMBAZHA itta) Ordinance ,PATHANAMTHIT 2020 TA CHECKAR VEEDU KUNNIL HOUSE 561/2021 PATHANA AZHAR 01-05-2021 47, KULASEKHARAPA U/s 279 IPC MTHITTA IBANU MIR BAILED BY 4 BINSU JOSEPH M.J ABAN at 09:30 Male THY & 3(1) r/w (Pathanamth SAHIB SI OF POLICE Hrs PATHANAMTHITT 181 MV Act itta) POLICE A 560/2021 HOUSE NO 21 U/s 4(2)(d) VADAKKEKARAI PATHANA 01-05-2021 of Kerala ABUBACKE 61, REHUMANIYAPU MTHITTA HAKKIM.K BAILED BY 5 AZAD STADIUM JN at -

Details of Quarries in Pathanamthitta District As on Date of Completion Of

Details of quarries in Pathanamthitta District as on date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of quarry) Code Mineral Rocktype Village Locality Owner Operator Adoor Taluk Granite(Building Sukumaran, Padmalayam, Sukumaran, Padmalayam, 10 Charnockite Koodal Pakkandam Stone) Murinjakal P.O., Koodal. Murinjakal P.O., Koodal Shaji, Puthenveettil Shaji, Puthenveettil thazhethil, Granite(Building 11 Charnockite Koodal Pakkandam thazhethil, Athirunkal P.O., Athirunkal P.O., Koodal, Ad, Stone) Koodal, Ad, Adoor. Adoor. Gangadharan, Granite(Building 12 Charnockite Koodal Pakkandam Revenue land Thumbamontharayil, Athirunkal Stone) P.O., Koodal. Granite(Building Suma, Sunimandiram, Athirunkal 13 Charnockite Koodal Athirunkal Revenue Stone) P.O. Gopinathan Nair S.M., Granite(Building Gopinathan Nair S.M., Niravel, 14 Charnockite Koodal Athirunkal Niravel, Athirunkal P.O., Stone) Athirunkal P.O., Koodal, Adoor. Koodal, Adoor. Granite(Building Sathyaseelan, Vazhavilayil, 15 Charnockite Koodal Athirunkal Revenue Stone) Athirunkal P.O. Granite(Building Thankappan, Nedumuruppel, Thankappan, Nedumuruppel, 16 Charnockite Koodal Pakkandam Stone) Athirunkal, Pakkandam. Athirunkal, Pakkandam. Granite(Building Renjan, Nalinivilasom, Murinjakal 17 Charnockite Koodal Athirunkal Revenue Stone) P.O., Athirunkal. Geevarghese, Anakkavil Granite(Building Geevarghese, Anakkavil veedu, 18 Charnockite Koodal Athirunkal veedu, Athirunkal, Koodal, Stone) Athirunkal, Koodal, Adoor. Adoor. Granite(Building 19 Charnockite Koodal Pakkandam Revenue Not known Stone) Granite(Building Cordierite T.K. Sundaresan, Aswathy, T.K. Sundaresan, Aswathy, 20 Kalanjoor Athirunkal Stone) Gneiss Sivankovil road , Punalurl. Sivankovil road, Punalurl Granite(Building Cordierite T.K Sundaresan, Aswathy, T.K Sundaresan, Aswathy, 22 Kalanjoor Athirunkal Stone) Gneiss Sivankovil Road, Punaloor. Sivankovil Road, Punaloor Granite(Building Charnockitic 23 Kalanjoor Athirunkal Not known Not known Stone) Gneiss Granite(Building P.T. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Pathanamthitta District from 05.11.2017 to 11.11.2017

Accused Persons arrested in Pathanamthitta district from 05.11.2017 to 11.11.2017 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1071/17, U/S. PERUMPARA 09.11.17,12.00 143,146,147,149, SANJAY CT, SI OF JFMC I 1 ABHILASH P.C PODIYAN 32/M HOUSEPERUMPARA, Vaipur Perumpetty PERUMPETTY Hrs 294(b),341,324,38 POLICE THIRUVALLA P.O, Kottangal 5,506(1) IPC 1071/17U/S. THRICHEPURATH HOUSE, 09.11.17 12.00 143,146,147,149, SANJAY CT, SI OF JFMC I 2 BINU T BABY BABY T.S 40/M PERUMPARA, VAIPUR P.O, Perumpetty Perumpetty Hrs 294(b),341,324,38 POLICE THIRUVALLA Kottangal 5,506(1) IPC 1071/17, U/S. THEKKADAYIL HOUSE 143,146,147,149, 09.11.17, SANJAY CT, SI OF JFMC I 3 THOMAS JOHN JOHN T.J 31/M PERUMPARA, VAIPUR P.O, Perumpetty 294(b), Perumpetty 12.00 Hrs POLICE THIRUVALLA Kottanagal 341,324,385, 506(1) IPC 1071/17 U/S. KARAMKATTIL HOUSE, 143,146,147,149, 09.11.17, SANJAY CT, SI OF JFMC I 4 AJI KUMAR GEORGE K.M 39/M PERUMPARA, PADIMON P.O, Perumpetty 294(b), Perumpetty 12.00 Hrs POLICE THIRUVALLA Kottangal 341,324,385, 506(1) IPC 1071/17 U/S. -

2001-02 - Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2001-02 - Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010102190 Shikamany T Manapazhinjiputhen Veedu,Nediyamcode,Parasuvaikal 0 C M R Furniture Mart Business Sector 47368 42632 26/05/2001 2 1 010103676 Vasantha D Tc 44/472,Puthuval Purayidam,Vallakkadavoo 0 C F U Dairy Unit Agriculture & Allied Sector 36842 33158 02/04/2001 1 2 010103702 Thankamony Vadakkekara Puthen Veedu,Marayamuttam,Marayamuttom 0 C F R Dairy Unit Agriculture & Allied Sector 21053 18947 02/04/2001 1 3 010103705 Chelladwara Raj Bn Cottage,Nattupara,Uriakode 0 C M R Stationery Business Sector 47368 42632 02/04/2001 1 4 010103706 Shibu G Charuvila Veedu,Kottukal,Nellimmodu 0 C M R Timber Bussiness Business Sector 36842 33158 02/04/2001 1 5 010103711 Wilson K Mohana Vilasam,Valukonam,Panacode 0 C M R Provision Store Business Sector 42105 37895 03/04/2001 1 6 010103721 Baby V Melekuzhinjavila Veedu,Karode,Karode 0 C F R Copra Unit Agriculture & Allied Sector 13684 12316 06/04/2001 1 7 010103741 Vinitha T Y Haritha,Puthenkada,Thiruppuram 0 C F R Copra Unit Agriculture & Allied Sector 47368 42632 09/04/2001 1 8 010103742 Mishiha Das Kondodi Veedu,Mavilakadavu,Uchakada 0 C M R Bricks Manufacturing Unit Business Sector 52632 47368 09/04/2001 1 9 010103747 Stephen T Sp Bhavan ,Vettuvila,Kunniyode,Kakkavila 0 C M R Milma Agency Agriculture & Allied Sector 52632 47368 10/04/2001 -

India, Ceylon and Burma 1927

CATHOLIC DIRECTORY OF INDIA, CEYLON AND BURMA 1927. PUBLISHED BY THE CATHOLIC SUPPLY SOCIETY, MADRAS. PRINTED AT THE “ GOOD PASTOR ” PRESS, BROADWAY, MADRAS. Yale Divinity tibn fj New Haven. Conn M T ^ h t € ¿ 2 ( 6 vA 7 7 Nihil obstat. C. RUYGROCK, Censor Deputatus. Imprimatur: * J. AELEN, Aichbishop of Madras. Madras, Slst January 1927. PREFACE. In introducing the Catholic Directory, it is our pleasing duty to reiterate our grateful thanks for the valuable assistance and in formation received from the Prelates and the Superiors of the Missions mentioned in this book. The compilation of the Catholic Direct ory involves no small amount of labour, which, however, we believe is not spent in vain, for the Directory seems to be of great use to many working in the same field. But We would like to see the Directory develop into a still more useful publication and rendered acceptable to a wider circle. This can only come about with the practical "sympathy and active co-operation of all ^ friends and well-wishers. We again give the Catholic Directory to ¿the public, knowing that it is still incom plete, but trusting that all and everyone will ¿help us to ensure its final success. ^ MADRAS, THE COMPILER* Feast of St. Agnes, 1 9 2 7 . CONTENTS. PAGE Agra ... ... ... ... 86 iljiner ... ... ... • •• ... 92 Allahabad ... ••• ••• ••• ••• 97 Apostolic Delegation (The) ... .. ... 26 Archbishops, Bishops and Apostolic Prefects ... 449 Assam ... ... ... ... ... 177 Bombay ... ... ... ... ... 104 Éurma (Eastern) ... ... ... ... 387 Burma (Northern) ... ... ... ... 392 Burma" (Southern) ... ... ... ... 396 Calcutta ... ... ... ... ... 158 Calicut' ... ... ... ... ... 114 Catholic Indian Association of S. India ... ... 426 CHanganacberry ... ... ... ... 201 Ódchin ... ... ... ... ... 51 Coimbatore ... ... ... ... 286 Colombo .. -

GOO-80-02119 392P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 228 863 FL 013 634 AUTHOR Hatfield, Deborah H.; And Others TITLE A Survey of Materials for the Study of theUncommonly Taught Languages: Supplement, 1976-1981. INSTITUTION Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, D.C.Div. of International Education. PUB DATE Jul 82 CONTRACT GOO-79-03415; GOO-80-02119 NOTE 392p.; For related documents, see ED 130 537-538, ED 132 833-835, ED 132 860, and ED 166 949-950. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Dictionaries; *InStructional Materials; Postsecondary Edtmation; *Second Language Instruction; Textbooks; *Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography is a supplement tothe previous survey published in 1976. It coverslanguages and language groups in the following divisions:(1) Western Europe/Pidgins and Creoles (European-based); (2) Eastern Europeand the Soviet Union; (3) the Middle East and North Africa; (4) SouthAsia;(5) Eastern Asia; (6) Sub-Saharan Africa; (7) SoutheastAsia and the Pacific; and (8) North, Central, and South Anerica. The primaryemphasis of the bibliography is on materials for the use of theadult learner whose native language is English. Under each languageheading, the items are arranged as follows:teaching materials, readers, grammars, and dictionaries. The annotations are descriptive.Whenever possible, each entry contains standardbibliographical information, including notations about reprints and accompanyingtapes/records -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt.