Characteristics and Seasonal Variations of Cirrus Clouds from Polarization Lidar Observations at a ◦ 30 N Plain Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward Non-Invasive Measurement of Atmospheric Temperature Using Vibro-Rotational Raman Spectra of Diatomic Gases

remote sensing Article Toward Non-Invasive Measurement of Atmospheric Temperature Using Vibro-Rotational Raman Spectra of Diatomic Gases Tyler Capek 1,*,† , Jacek Borysow 1,† , Claudio Mazzoleni 1,† and Massimo Moraldi 2,† 1 Department of Physics, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (C.M.) 2 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Universita’ degli Studi di Firenze, via Sansone 1, I-50019 Sesto Fiorentino, Italy; massimo.moraldi@fi.infn.it * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 8 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 17 December 2020 Abstract: We demonstrate precise determination of atmospheric temperature using vibro-rotational Raman (VRR) spectra of molecular nitrogen and oxygen in the range of 292–293 K. We used a continuous wave fiber laser operating at 10 W near 532 nm as an excitation source in conjunction with a multi-pass cell. First, we show that the approximation that nitrogen and oxygen molecules behave like rigid rotors leads to erroneous derivations of temperature values from VRR spectra. Then, we account for molecular non-rigidity and compare four different methods for the determination of air temperature. Each method requires no temperature calibration. The first method involves fitting the intensity of individual lines within the same branch to their respective transition energies. We also infer temperature by taking ratios of two isolated VRR lines; first from two lines of the same branch, and then one line from the S-branch and one from the O-branch. Finally, we take ratios of groups of lines. -

Global Modeling of Contrail and Contrail Cirrus Climate Impact

GLOBAL MODELING OF THE CONTRAIL AND CONTRAIL CIRRUS CLIMATE IMPACT BY ULRIKE BU RKHARDT , BERND KÄRCHER , AND ULRICH SCH U MANN et al. 2010). For the given ambient Modeling the physical processes governing the life cycle of conditions, their direct radia- contrail cirrus clouds will substantially narrow the uncer- tive effect is mainly determined tainty associated with the aviation climate impact. by coverage and optical depth. The microphysical properties of contrail cirrus likely differ from substantial part of the aviation climate impact those of most natural cirrus, at least during the initial may be due to aviation-induced cloudiness (AIC; stages of the contrail cirrus life cycle (Heymsfield A Brasseur and Gupta 2010), which is arguably et al. 2010). Contrails form and persist in air that is the most important but least understood component ice saturated, whereas natural cirrus usually requires in aviation climate impact assessments. The AIC in- high ice supersaturation to form (Jensen et al. 2001). cludes contrail cirrus and changes in cirrus properties This difference implies that in a substantial fraction or occurrence arising from aircraft soot emissions of the upper troposphere contrail cirrus can persist in (soot cirrus). Linear contrails are line-shaped ice supersaturated air that is cloud free, thus increasing clouds that form behind cruising aircraft in clear air high cloud coverage. Contrails and contrail cirrus and within cirrus clouds. Linear contrails transform existing above, below, or within clouds change the into irregularly shaped ice clouds (contrail cirrus) and column optical depth and radiative fluxes. They may may form cloud clusters in favorable meteorological also indirectly affect radiation by changing the mois- conditions, occasionally covering large horizontal ture budget of the upper troposphere, and therefore areas extending up to 100,000 km2 (Duda et al. -

CHAPTER CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 5. SPECIAL PROFILING TECHNIQUES FOR THE BOUNDARY LAYER AND THE TROPOSPHERE .............................................................. 640 5.1 General ................................................................... 640 5.2 Surface-based remote-sensing techniques ..................................... 640 5.2.1 Acoustic sounders (sodars) ........................................... 640 5.2.2 Wind profiler radars ................................................. 641 5.2.3 Radio acoustic sounding systems ...................................... 643 5.2.4 Microwave radiometers .............................................. 644 5.2.5 Laser radars (lidars) .................................................. 645 5.2.6 Global Navigation Satellite System ..................................... 646 5.2.6.1 Description of the Global Navigation Satellite System ............. 647 5.2.6.2 Tropospheric Global Navigation Satellite System signal ........... 648 5.2.6.3 Integrated water vapour. 648 5.2.6.4 Measurement uncertainties. 649 5.3 In situ measurements ....................................................... 649 5.3.1 Balloon tracking ..................................................... 649 5.3.2 Boundary layer radiosondes .......................................... 649 5.3.3 Instrumented towers and masts ....................................... 650 5.3.4 Instrumented tethered balloons ....................................... 651 ANNEX. GROUND-BASED REMOTE-SENSING OF WIND BY HETERODYNE PULSED DOPPLER LIDAR ................................................................ -

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

Observation of Polar Stratospheric Clouds Down to the Mediterranean Coast

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 7, 5275–5281, 2007 www.atmos-chem-phys.net/7/5275/2007/ Atmospheric © Author(s) 2007. This work is licensed Chemistry under a Creative Commons License. and Physics Observation of Polar Stratospheric Clouds down to the Mediterranean coast P. Keckhut1, Ch. David1, M. Marchand1, S. Bekki1, J. Jumelet1, A. Hauchecorne1, and M. Hopfner¨ 2 1Service d’Aeronomie,´ Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, B.P. 3, 91371, Verrieres-le-Buisson,` France 2Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe, Institut fur¨ Meteorologie und Klimaforschung, Karlsruhe, Germany Received: 8 March 2007 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 15 May 2007 Revised: 5 October 2007 – Accepted: 6 October 2007 – Published: 12 October 2007 Abstract. A Polar Stratospheric Cloud (PSC) was detected spheric temperatures are expected to cool down due to ozone for the first time in January 2006 over Southern Europe af- depletion, but also to the increase in the concentrations of ter 25 years of systematic lidar observations. This cloud greenhouse gases. Such findings are already reported and was observed while the polar vortex was highly distorted simulated (Ramaswamy et al., 2001), although trends are less during the initial phase of a major stratospheric warming. clear at high latitudes due to a larger natural variability and Very cold stratospheric temperatures (<190 K) centred over potential dynamical feedback. Nearly twenty years after the the Northern-Western Europe were reported, extending down signing of the Montreal Protocol, the timing and extent of the to the South of France -

Fraunhofer Lidar Prototype in the Green Spectral Region for Atmospheric Boundary Layer Observations

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 6079-6095; doi:10.3390/rs5116079 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Fraunhofer Lidar Prototype in the Green Spectral Region for Atmospheric Boundary Layer Observations Songhua Wu *, Xiaoquan Song and Bingyi Liu Ocean Remote Sensing Institute, Ocean University of China, 238 Songling Road, Qingdao 266100, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (X.S.); [email protected] (B.L.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-532-6678-2573. Received: 8 October 2013; in revised form: 27 October 2013 / Accepted: 13 November 2013 / Published: 18 November 2013 Abstract: A lidar detects atmospheric parameters by transmitting laser pulse to the atmosphere and receiving the backscattering signals from molecules and aerosol particles. Because of the small backscattering cross section, a lidar usually uses the high sensitive photomultiplier and avalanche photodiode as detector and uses photon counting technology for collection of weak backscatter signals. Photon Counting enables the capturing of extremely weak lidar return from long distance, throughout dark background, by a long time accumulation. Because of the strong solar background, the signal-to-noise ratio of lidar during daytime could be greatly restricted, especially for the lidar operating at visible wavelengths where solar background is prominent. Narrow band-pass filters must therefore be installed in order to isolate solar background noise at wavelengths close to that of the lidar receiving channel, whereas the background light in superposition with signal spectrum, limits an effective margin for signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement. This work describes a lidar prototype operating at the Fraunhofer lines, the invisible band of solar spectrum, to achieve photon counting under intense solar background. -

Manuscript Was Written Jointly by YL, CK, and MZ

A simplified method for the detection of convection using high resolution imagery from GOES-16 Yoonjin Lee1, Christian D. Kummerow1,2, Milija Zupanski2 1Department of Atmospheric Science, Colorado state university, Fort Collins, CO 80521, USA 5 2Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, Colorado state university, Fort Collins, CO 80521, USA Correspondence to: Yoonjin Lee ([email protected]) Abstract. The ability to detect convective regions and adding heating in these regions is the most important skill in forecasting severe weather systems. Since radars are most directly related to precipitation and are available in high temporal resolution, their data are often used for both detecting convection and estimating latent heating. However, radar data are limited to land areas, 10 largely in developed nations, and early convection is not detectable from radars until drops become large enough to produce significant echoes. Visible and Infrared sensors on a geostationary satellite can provide data that are more sensitive to small droplets, but they also have shortcomings: their information is almost exclusively from the cloud top. Relatively new geostationary satellites, Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites-16 and -17 (GOES-16 and GOES-17), along with Himawari-8, can make up for some of this lack of vertical information through the use of very high spatial and temporal 15 resolutions. This study develops two algorithms to detect convection at vertically growing clouds and mature convective clouds using 1-minute GOES-16 Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) data. Two case studies are used to explain the two methods, followed by results applied to one month of data over the contiguous United States. -

Assessing and Improving Cloud-Height Based Parameterisations of Global Lightning Flash Rate, and Their Impact on Lightning-Produced Nox and Tropospheric Composition

https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-885 Preprint. Discussion started: 2 October 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Assessing and improving cloud-height based parameterisations of global lightning flash rate, and their impact on lightning-produced NOx and tropospheric composition 5 Ashok K. Luhar1, Ian E. Galbally1, Matthew T. Woodhouse1, and Nathan Luke Abraham2,3 1CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Aspendale, 3195, Australia 2National Centre for Atmospheric Science, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 3Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 10 Correspondence to: Ashok K. Luhar ([email protected]) Abstract. Although lightning-generated oxides of nitrogen (LNOx) account for only approximately 10% of the global NOx source, it has a disproportionately large impact on tropospheric photochemistry due to the conducive conditions in the tropical upper troposphere where lightning is mostly discharged. In most global composition models, lightning flash rates used to calculate LNOx are expressed in terms of convective cloud-top height via the Price and Rind (1992) (PR92) 15 parameterisations for land and ocean. We conduct a critical assessment of flash-rate parameterisations that are based on cloud-top height and validate them within the ACCESS-UKCA global chemistry-climate model using the LIS/OTD satellite data. While the PR92 parameterisation for land yields satisfactory predictions, the oceanic parameterisation underestimates the observed flash-rate density severely, yielding a global average of 0.33 flashes s-1 compared to the observed 9.16 -1 flashes s over the ocean and leading to LNOx being underestimated proportionally. We formulate new/alternative flash-rate 20 parameterisations following Boccippio’s (2002) scaling relationships between thunderstorm electrical generator power and storm geometry coupled with available data. -

Cloud-Base Height Derived from a Ground-Based Infrared Sensor and a Comparison with a Collocated Cloud Radar

VOLUME 35 JOURNAL OF ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC TECHNOLOGY APRIL 2018 Cloud-Base Height Derived from a Ground-Based Infrared Sensor and a Comparison with a Collocated Cloud Radar ZHE WANG Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, CMA Key Laboratory for Aerosol–Cloud–Precipitation, and School of Atmospheric Physics, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, and Training Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing, China ZHENHUI WANG Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, CMA Key Laboratory for Aerosol–Cloud–Precipitation, and School of Atmospheric Physics, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, China XIAOZHONG CAO,JIAJIA MAO,FA TAO, AND SHUZHEN HU Atmosphere Observation Test Bed, and Meteorological Observation Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing, China (Manuscript received 12 June 2017, in final form 31 October 2017) ABSTRACT An improved algorithm to calculate cloud-base height (CBH) from infrared temperature sensor (IRT) observations that accompany a microwave radiometer was described, the results of which were compared with the CBHs derived from ground-based millimeter-wavelength cloud radar reflectivity data. The results were superior to the original CBH product of IRT and closer to the cloud radar data, which could be used as a reference for comparative analysis and synergistic cloud measurements. Based on the data obtained by these two kinds of instruments for the same period (January–December 2016) from the Beijing Nanjiao Weather Observatory, the results showed that the consistency of cloud detection was good and that the consistency rate between the two datasets was 81.6%. The correlation coefficient between the two CBH datasets reached 0.62, based on 73 545 samples, and the average difference was 0.1 km. -

METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N JO 7900.11 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Effective Date: Air Traffic Organization Policy September 1, 2018 Cancellation Date: September 1, 2019 SUBJ: METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR) 1. Purpose of this Notice. This Notice coincides with a revision to the Federal Meteorological Handbook (FMH-1) that was effective on November 30, 2017. The Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (OFCM) approved the changes to the reporting requirements of small hail and snow pellets in weather observations (METAR/SPECI) to assist commercial operators in deicing operations. 2. Audience. This order applies to all FAA and FAA-contract weather observers, Limited Aviation Weather Reporting Stations (LAWRS) personnel, and Non-Federal Observation (NF- OBS) Program personnel. 3. Where can I Find This Notice? This order is available on the FAA Web site at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and http://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. 4. Cancellation. This notice will be cancelled with the publication of the next available change to FAA Order 7900.5D. 5. Procedures/Responsibilities/Action. This Notice amends the following paragraphs and tables in FAA Order 7900.5. Table 3-2: Remarks Section of Observation Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Volcanic eruptions must be reported whenever first noted. Pre-eruption activity must not be reported. (Use Volcanic Eruptions 14.20 X X PIREPs to report pre-eruption activity.) Encode volcanic eruptions as described in Chapter 14. Distribution: Electronic 1 Initiated By: AJT-2 09/01/2018 N JO 7900.11 Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Whenever tornadoes, funnel clouds, or waterspouts begin, are in progress, end, or disappear from sight, the event should be described directly after the "RMK" element. -

Observations of Atmospheric Aerosol and Cloud Using a Polarized Micropulse Lidar in Xi’An, China

atmosphere Article Observations of Atmospheric Aerosol and Cloud Using a Polarized Micropulse Lidar in Xi’an, China Chao Chen 1,2,3,4, Xiaoquan Song 1,* , Zhangjun Wang 1,2,3,4,*, Wenyan Wang 5, Xiufen Wang 2,3,4, Quanfeng Zhuang 2,3,4, Xiaoyan Liu 1,2,3,4 , Hui Li 2,3,4, Kuntai Ma 1, Xianxin Li 2,3,4, Xin Pan 2,3,4, Feng Zhang 2,3,4, Boyang Xue 2,3,4 and Yang Yu 2,3,4 1 College of Information Science and Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (K.M.) 2 Institute of Oceanographic Instrumentation, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy of Sciences), Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (X.L.); [email protected] (X.P.); [email protected] (F.Z.); [email protected] (B.X.); [email protected] (Y.Y.) 3 Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Marine Monitoring Instrument Equipment Technology, Qingdao 266100, China 4 National Engineering and Technological Research Center of Marine Monitoring Equipment, Qingdao 266100, China 5 Xi’an Meteorological Bureau of Shanxi Province, Xi’an 710016, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.S.); [email protected] (Z.W.) Abstract: A polarized micropulse lidar (P-MPL) employing a pulsed laser at 532 nm was developed by the Institute of Oceanographic Instrumentation, Qilu University of Technology (Shandong Academy Citation: Chen, C.; Song, X.; Wang, of Sciences). -

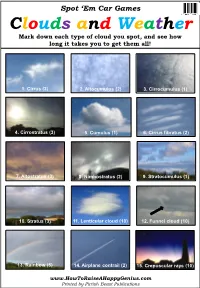

Cloud-Spotting Game Sheet

Spot ‘Em Car Games Clouds and Weather Mark down each type of cloud you spot, and see how long it takes you to get them all! 1. Cirrus (2) 2. Altocumulus (2) 3. Cirrocumulus (1) 4. Cirrostratus (3) 5. Cumulus (1) 6. Cirrus fibratus (2) 7. Altostratus (3) 8. Nimbostratus (2) 9. Stratocumulus (1) 10. Stratus (3) 11. Lenticular cloud (10) 12. Funnel cloud (10) 13. Rainbow (5) 14. Airplane contrail (2) 15. Crepuscular rays (10) www.HowToRaiseAHappyGenius.com Printed by Pictish Beast Publications Spot ‘Em Car Games Clouds and Weather More information about how to identify the weather phenomena that are part of this car game 1. Cirrus: Cirrus clouds look like strands of white cotton wool that have been pulled apart and spread across the sky. 2. Altocumulus: Altocumulus clouds form a layer at mid-altitudes that covers much of the sky, and this layer is usually made up of patterns of regularly spaced and shaped patches with bands of blue sky between them. 3. Cirrocumulus: Cirrocumulus clouds are similar to altocumulus, but they are found higher up in the sky and are made up of smaller patches of cloud. 4. Cirrostratus: Cirrostratus clouds form a continuous sheet of cloud high up in the sky that are thin enough for the sun to be able to shine through, creating a halo effect. 5. Cumulus: Cumulus clouds are distinctive fluffy looking clouds that are clearly separated from other clouds in the sky. They are what you would draw if asked to draw a picture of a cloud. 6. Cirrus fibratus: Cirrus fibratus are a type of Cirrus cloud that form very distinctive long, fluffy lines across the sky.