Birkbeck Sport Business Centre Research Paper Series GAMBLING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Too Big to Fail? Accounting for Predictions of Financial Distress In

Too big to fail? Accounting for Predictions of Financial Distress in English Professional Football Clubs PLUMLEY, Daniel <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7875-0969>, SERBERA, Jean- Philippe and WILSON, rob Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/27518/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version PLUMLEY, Daniel, SERBERA, Jean-Philippe and WILSON, rob (2020). Too big to fail? Accounting for Predictions of Financial Distress in English Professional Football Clubs. Journal of Applied Accounting Research. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Too big to fail? Accounting for Predictions of Financial Distress in English Professional Football Clubs Abstract Purpose This paper analyses English Premier League (EPL) and English Football League (EFL) Championship clubs during the period 2002-2019 to anticipate financial distress with specific reference to footballs’ Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations. Design/Methodology/Approach Data was collected for 43 professional football clubs competing in the EPL and Championship for the financial year ends 2002-2019. Analysis was conducted using the Z-score methodology and additional statistical tests were conducted to measure differences between groups. Data was split into two distinct periods to analyse club finances pre and post-FFP. Findings The results show significant cases of financial distress amongst clubs in both divisions and that Championship clubs are in significantly poorer financial health than EPL clubs. In some cases, financially sustainability has worsened post-FFP. -

Acquisition Opportunity: Profitable English Football League Two ("EFL Two") Club with Loyal Fan Base

Acquisition Opportunity: Profitable English Football League Two ("EFL Two") Club with Loyal Fan Base "The Company” is an English Football League Two club with loyal fan base near London in the United Kingdom. The EFL has a proud history and was formed over 115 years ago. The purchase includes all tangible and intangible assets associated with the club. The club currently leases its home stadium and operates several food services outlets including walk-up counters, bars and restaurants. The club’s home stadium boasts a seating capacity of over 6,000. Additionally, the purchase includes a variety maintenance equipment and all player contracts.. Key Acquisition Considerations Highlights Business Description $11.770M English Football League (EFL) was formed in 1888 by its twelve founder members and is the 2020 Revenue world's original league football competition. The EFL is the template used by leagues the world over. The EFL is the largest single body of professional Clubs in European football $.706M and is responsible for administering and regulating the EFL, the Carabao Cup and the Papa John’s Trophy, as well as reserve and youth football. The EFL's 72 member clubs are 2020 Cashflow grouped into three divisions: the EFL Championship, EFL League One, and EFL League Two 6.0% League Two Cashflow Margin There are 24 clubs in the EFL League Two. Each season, clubs play each of the other teams twice (once at home, once away). Clubs are awarded three points for a win, one for a draw 115yrs and no points for a loss. Over the season, these points are tallied, and a league table is Time since Inception constructed. -

The Big Mind Footy Quiz Questions

The Big Mind Footy Quiz As part of Mind’s partnership with The English Football League Questions 1 How many clubs make up the three EFL Divisions (The EFL Championship; EFL League One and EFL League Two)? 2 Can you name the two EFL knockout cup competitions? 3 What season was the EFL Cup (The Football League Cup as it was previously known) introduced? 4 And which club won the first EFL Cup? 5 There are five EFL clubs with ‘Rovers’ in their name, can you name them? (A point for each correct Team) 6 Can you name the team who finished the 2005-06 season as The EFL Championship winners with a record points total? (Bonus point for the points total) 7 Who were the first team to win the Football League Title (1888/89 Season) 8 Can you name the three Welsh clubs who play in the EFL? 9 Can you name the two EFL clubs who are based in Cumbria? 10 Who used to play their home games at Highfield Road? 11 Which EFL club are known as The Tractor Boys? The Big Mind Footy Quiz As part of Mind’s partnership with The English Football League Answers 1 72 2 The EFL Cup (currently known as The Carabao Cup) and The EFL Trophy (currently known as The Papa Johns Trophy) 3 1960/61 4 Aston Villa 5 Blackburn Rovers; Bristol Rovers; Doncaster Rovers; Forest Green Rovers; Tranmere Rovers 6 Reading. (Bonus point: 106 points) 7 Preston North End 8 Cardiff, Swansea and Newport County 9 Barrow AFC and Carlisle United 10 Coventry City 11 Ipswich Town . -

Procedural Rules

SR/Adhocsport/253/2019 IN THE MATTER OF AN EFL DISCIPLINARY COMMISSION Before: Charles Flint QC BETWEEN: - THE ENGLISH FOOTBALL LEAGUE (the EFL) Claimant -and- BIRMINGHAM CITY FOOTBALL CLUB (the Club) Respondent DECISION James Segan, instructed by Solesbury Gay and Nick Craig (Governance and Legal Director) for the EFL Kendrah Potts and William Harman instructed by Ciara Gallagher (Club Secretary) for the Club 1. By a decision dated 22 March 2019 a Disciplinary Commission, which I chaired, imposed a deduction of 9 points on the Club for its admitted breaches of Rule 2.9 of the Profitability and Sustainability Rules (the P&S Rules) by incurring adjusted losses totalling £48.79 million over a monitoring period comprising the seasons 2015/16, 2016/17 and 2017/18. Those losses exceeded the permitted upper loss threshold by £9.79 million. - 1 - 2. By a letter dated 14 May 2019 the EFL gave notice to the Club of the reference to a Disciplinary Commission of proceedings arising out of the Club’s failure to comply with a direction made when the EFL imposed a business plan on the Club by letter dated 1 August 2018, as amended. 3. The proceedings are brought under the EFL Regulations (the Regulations) and the P&S Rules. Regulation 1.1 provides that misconduct includes a breach of a requirement or direction of the EFL. P&S Rule 2.9 provides that if a club’s earnings result in a loss that exceeds a stipulated threshold, the executive of the EFL may exercise the powers set out in Regulation 16.20. -

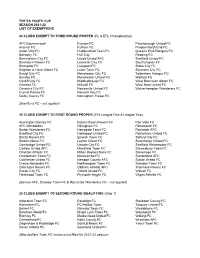

The Emirates Fa Cup Season 2021-22 List of Exemptions

THE EMIRATES FA CUP SEASON 2021-22 LIST OF EXEMPTIONS 44 CLUBS EXEMPT TO THIRD ROUND PROPER (PL & EFL Championship) AFC Bournemouth Derby County FC Nottingham Forest FC Arsenal FC Everton FC Peterborough United FC Aston Villa FC Fulham FC Preston North End FC Barnsley FC Huddersfield Town FC Queens Park Rangers FC Birmingham City FC Hull City Reading FC Blackburn Rovers FC Leeds United AFC Sheffield United FC Blackpool FC Leicester City FC Southampton FC Brentford FC Liverpool FC Stoke City FC Brighton & Hove Albion FC Luton Town FC Swansea City FC Bristol City FC Manchester City FC Tottenham Hotspur FC Burnley FC Manchester United FC Watford FC Cardiff City FC Middlesbrough FC West Bromwich Albion FC Chelsea FC Millwall FC West Ham United FC Coventry City FC Newcastle United FC Wolverhampton Wanderers FC Crystal Palace FC Norwich City FC 48 CLUBS EXEMPT TO FIRST ROUND PROPER (EFL League One & League Two) Accrington Stanley FC Fleetwood Town FC Port Vale FC AFC Wimbledon Forest Green Rovers FC Portsmouth FC Barrow AFC Gillingham FC Rochdale AFC Bolton Wanderers FC Harrogate Town FC Rotherham United FC Bradford City FC Hartlepool United FC Salford City FC Bristol Rovers FC Ipswich Town FC Scunthorpe United FC Burton Albion FC Leyton Orient FC Sheffield Wednesday FC Cambridge United FC Lincoln City FC Shrewsbury Town FC Carlisle United AFC Mansfield Town FC Stevenage FC Charlton Athletic FC Milton Keynes Dons FC Sunderland AFC Cheltenham Town FC Morecambe FC Sutton United FC Colchester United FC Newport County AFC Swindon Town FC Crawley -

The Relationship Between Team Ability and Home Advantage in the English Football League System

The relationship between team ability and home advantage in the English football league system RAMCHANDANI, Girish <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8650-9382>, MILLAR, Robbie and WILSON, Darryl Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/28515/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RAMCHANDANI, Girish, MILLAR, Robbie and WILSON, Darryl (2021). The relationship between team ability and home advantage in the English football league system. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 51 (3), 354-361. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Main Article Ger J Exerc Sport Res Girish Ramchandani · Robbie Millar · Darryl Wilson https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-021-00721-x Academy of Sport and Physical Activity, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK Received: 9 July 2020 Accepted: 16 April 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 The relationship between team ability and home advantage in the English football league system Introduction for men’s and women’s competition. Te 1995). In other words, performance has HA found for football in the Pollard two components, namely: quality and Te phenomenon of home advantage et al. (2017a) study was somewhat below HA. If every team in a league enjoys the (HA), where home teams in sports com- its historical position relative to other same level of HA, then performance is petitions win over half of the games sports. Within football, the existence dependent on quality alone; however, played under a balanced home and away of HA across national domestic leagues if some teams have superior HA then schedule (Courneya & Carron, 1992), worldwide was illustrated by Pollard their performance will be naturally en- has received widespread attention from and Gomez (2014a). -

The Probability of Relegation in the First Three Seasons in the Premier League Ryan Alty

The Probability of Relegation in the First Three Seasons in The Premier League Ryan Alty Abstract This paper will offer an insight into the probabilities of newly promoted English Premier League teams suffering relegation within three years of being promoted to the top flight of English football. This will be done by investigating possible trends of promoted teams and checking whether they are likely to return to the second tier of English Football within the given time period, based on results over the past 22 seasons. Introduction The 2018/19 English Premier League season was remarkable in many ways. We witnessed a record-breaking 100 points[3] out of a possible 114 for the first time since the introduction of the league. In this season, we also had the first English representatives in the UEFA Champions League final for the first time in 6 years. Also, all three newly promoted teams avoiding relegation for only the third time since the incarnation of the Premier League in 1992. The fortunes of the newly promoted teams over the years shall be investigated to calculate the probability that a newly promoted team would suffer relegation within 3 years of achieving promotion to the English Premier League. The probability of relegation within one year, within two years and within three years of promotion to the top flight of English football is to be explored. Overview The English Premier League was formed in 1992 initially with 22 teams, however in 1995, the league was reduced to 20 teams[5]. As a result of this, the only data involved is the data since the alterations to the number of teams in the league, in order to reduce the number of variables that could skew the findings. -

Charter for Academy Players and Parents

CONTACTS • CONTENTS • WELCOME • THE ACADEMY SYSTEM • PARTICIPATION • ACADEMY PERFORMANCE PLAN • PLAYER RECOGNITION SYSTEM • PLAYER DEVELOPMENT AND PROGRESSION PLAYER AND SAFEGUARDING WELFARE • INDEPENDENT ADVICE • FEEDBACK • KEY CONTACTS • THE FA RESPECT PROGRAMME • YOUNG PLAYERS RESPECT CODE OF CONDUCT SPECTATORS RESPECT CODE OF CONDUCT • FA EDUCATION AND WELFARE STATEMENT • APPRENTICESHIPS • TRIALS • YOUTH DEVELOPMENT RULES • CONFIRMATION OF RECEIPT CHARTER FOR AcADEMY PLAYERS EFL YOUTH DEVELOPMENT AND PARENTS PLAYERS’ and pARENTS’ guidE SEASON 2017/18 EFL YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PLAYERS’ and pARENTS’ guidE SEASON 2017/18 CONTACTS • CONTENTS • WELCOME • THE ACADEMY SYSTEM • PARTICIPATION • ACADEMY PERFORMANCE PLAN • PLAYER RECOGNITION SYSTEM • PLAYER DEVELOPMENT AND PROGRESSION PLAYER AND SAFEGUARDING WELFARE • INDEPENDENT ADVICE • FEEDBACK • KEY CONTACTS • THE FA RESPECT PROGRAMME • YOUNG PLAYERS RESPECT CODE OF CONDUCT SPECTATORS RESPECT CODE OF CONDUCT • FA EDUCATION AND WELFARE STATEMENT • APPRENTICESHIPS • TRIALS • YOUTH DEVELOPMENT RULES • CONFIRMATION OF RECEIPT ENGLISH FOOTBALL CONTACTS LEAGUE (EFL) STAFF CONTACTS CONTENTS CHARTER EFL YOUTH DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT EFL EFL Youth Development Director EFL House 1 THE ACADEMY SYSTEM ......................................... 6 Dave Wetherall T 07552 166367 10-12 West Cliff OUR VISION ........................................................................... 6 Preston EFL Youth Development Business and Operations Manager OUR MISSION ........................................................................ -

LIVE SPORT TV GUIDE May 11May-31

LIVE SPORT TV GUIDE May 11May-31 ContentContent is is correct correct at at time time of of print print (27(28(11/10/5/4) )and and is is subject subject to to change change SB_A4_LISTINGS_COVERS_300421.indd 1 12/05/2021 10:34 MAJOR LIVE EVENT / EDITOR’S CHOICE tuesday 11 / MAY LIVE 10AM-12NOON LIVE 10AM-12NOON 7.30-8.30PM 6AM-MIDNIGHT 4.30-7.30PM LIVE 12NOON-4PM THE FOOTBALL THE FOOTBALL EFL GOALS: BEST OF THE 2014 HOW THE 2006 WORLD CUP OF SHOW SHOW LEAGUES 1 & 2 T20 BLAST RYDER CUP POOL: DAY 3 Top pundits and Top pundits and A round-up of the A full day of big- WAS WON Three first-round big-name guests take big-name guests take latest goals in Sky hitting cricket from The story of the 36th games live from a look at the latest a look at the latest Bet League 1, followed the 2014 edition of Ryder Cup, held at Stadium MK in Milton football news. news from around by goals galore from the NatWest T20 the K Club in County Keynes. The fixtures the football world. Sky Bet League 2. blast, with all the Kildare, Ireland. Ian are: Philippines action from five key Woosnam’s Europe v Great Britain B, LIVE 12NOON-4PM matches. This was romped to an 18½-9½ Poland v Kuwait and WORLD CUP OF 7-8PM 8.30-9PM the first season of victory over Tom Kite’s Estonia v Belgium. POOL: DAY 3 PREMIER LEAGUE MLS ROUND-UP England’s domestic United States team. -

The Fa Youth Cup Season 2021-22 List of Exemptions

THE FA YOUTH CUP SEASON 2021-22 LIST OF EXEMPTIONS 43 CLUBS EXEMPT TO THIRD ROUND PROPER (PL & EFL Championship) AFC Bournemouth Everton FC Peterborough United FC Arsenal FC Fulham FC Preston North End FC Aston Villa FC Huddersfield Town FC Queens Park Rangers FC Barnsley FC Hull City Reading FC Birmingham City FC Leeds United AFC Sheffield United FC Blackburn Rovers FC Leicester City FC Southampton FC Blackpool FC Liverpool FC Stoke City FC Brighton & Hove Albion FC Luton Town FC Swansea City FC Bristol City FC Manchester City FC Tottenham Hotspur FC Burnley FC Manchester United FC Watford FC Cardiff City FC Middlesbrough FC West Bromwich Albion FC Chelsea FC Millwall FC West Ham United FC Coventry City FC Newcastle United FC Wolverhampton Wanderers FC Crystal Palace FC Norwich City FC Derby County FC Nottingham Forest FC (Brentford FC – not applied) 45 CLUBS EXEMPT TO FIRST ROUND PROPER (EFL League One & League Two) Accrington Stanley FC Forest Green Rovers FC Port Vale FC AFC Wimbledon Gillingham FC Portsmouth FC Bolton Wanderers FC Harrogate Town FC Rochdale AFC Bradford City FC Hartlepool United FC Rotherham United FC Bristol Rovers FC Ipswich Town FC Salford City FC Burton Albion FC Leyton Orient FC Scunthorpe United FC Cambridge United FC Lincoln City FC Sheffield Wednesday FC Carlisle United AFC Mansfield Town FC Shrewsbury Town FC Charlton Athletic FC Milton Keynes Dons FC Stevenage FC Cheltenham Town FC Morecambe FC Sunderland AFC Colchester United FC Newport County AFC Sutton United FC Crewe Alexandra FC Northampton Town FC -

Socioeconomic and Other Dynamics in the Geographical Distribution of Success in the English F.A. Cup

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2021 Socioeconomic and Other Dynamics in the Geographical Distribution of Success in the English F.A. Cup Edward Genereux Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Human Geography Commons, Income Distribution Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Genereux, E. (2021). Socioeconomic and other dynamics in the geographic distribution of success in the English F.A. Cup [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ etds/1121/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Socioeconomic and Other Dynamics in the Geographical Distribution of Success in the English F.A. Cup Edward Genereux A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Geography Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota May 2021 i 2 April 2021 Socioeconomic and Other Dynamics in the Geographic Distribution of Success in the English F.A. Cup Edward Genereux This thesis has been examined and approved by the following members of the student’s committee: ______________________ Martin Mitchell, PhD. -

Head of Communications | PGMOL

Head of Communications | PGMOL Candidate brief for the position of Head of Communications PGMOL July 2021 odgersberndtson.com 1 Head of Communications | PGMOL Contents About PGMOL 3 Opportunity 4 The Individual 6 Search Process 8 Candidate Charter 9 Contact details 10 odgersberndtson.comodgersberndtson.com 2 Head of Communications | PGMOL About PGMOL Formed in 2001 to improve refereeing standards, Professional Game Match Officials Limited (PGMOL) officiate across all the Premier League, English Football League (EFL) and Football Association (FA) Competitions – with all three organisations funding it. The training, development and mentoring of more than 600 match officials and observers, is run by Managing Director Mike Riley (a former PGMOL referee) and a team of managers, coaches, sports scientists, psychologists and analysts. There are currently four levels of PGMOL match officials: Select Group 1 – Officiate Premier League, matches, operating on-field as well as VAR. Some Select Group 1 officials are appointed to the FIFA list and officiate Champions League and Europa League matches. There are 22 full-time professional Select Group One referees and 28 full time professional Select Group 1 assistant referees. Select Group 2 – Officiate EFL Championship matches and occasionally EFL League One and League Two games. Select Group 2 can also operate as fourth officials at Premier League matches. There are 18 professional Select Group 2 referees. National Group – Officiate EFL League One and League Two matches and are occasionally fourth officials in the Championship. There are almost 200 referees and assistant referees operating at this level. Women’s Select Group – PGMOL recently confirmed the transition of officiating in the women’s professional game from the FA to PGMOL.