Physical Setting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Santa Ana River Watershed?

32 1 32 1 2 3 Discharge of the Santa Ana River Below Prado Dam Water Year 1969 - 1970 2 3 4 5 – Gordon K. Anderson, former Chief of Planning, California Regional Water Quality Control Board “Too many people and not enough water to go around – that’s what led to the seemingly endless rounds of lawsuits and countersuits that characterized the 1960s in this watershed [which] takes in parts of three separate counties.” – Gordon K. Anderson, former Chief of Planning, California Regional Water Quality Control Board 1 4 5 6 7 ItIt All All StartedStarted withwith ConflictConflict AfterAfter decades decades of of disputes disputes dating dating to to the the early early 1900s, 1900s, two two major major lawsuits lawsuits were were filedfiled in in 1963, 1963, involving involving surface surface water water and and groundwater groundwater pumping pumping rights rights in in thethe Santa Santa Ana Ana River River Watershed. Watershed. One One lawsuit lawsuit was was filed filed by by Western Western MunicipalMunicipal Water Water District District and and the the other other by by Orange Orange County County Water Water District. District. InIn reference reference to to the the Orange Orange County County lawsuit, lawsuit, Corona Corona City City Attorney Attorney Robert Robert TimlinTimlin and and Don Don Stark, Stark, Counsel Counsel for for the the Chino Chino Basin Basin Municipal Municipal Water Water District,District, declared declared in in 1968, 1968, “The “The suit suit was was the the largest largest and and most most complex complex ever -

Santa Margarita River Trail Preserve Acquisition

COASTAL CONSERVANCY Staff Recommendation September 6, 2018 SANTA MARGARITA RIVER TRAIL PRESERVE ACQUISITION Project No. 18-015-01 Project Manager: Greg Gauthier RECOMMENDED ACTION: Authorization to disburse up to $9,750,000 to The Wildlands Conservancy for acquisition of approximately 1,390 acres along the Santa Margarita River for conservation and recreation purposes. LOCATION: Santa Margarita River, County of San Diego PROGRAM CATEGORY: Integrated Coastal and Marine Resource Protection EXHIBITS Exhibit 1: Project Location, Site Map, and APN Numbers Exhibit 2: Santa Margarita River Trail Preserve Photographs Exhibit 3: Project Letters RESOLUTION AND FINDINGS: Staff recommends that the State Coastal Conservancy adopt the following resolution pursuant to Chapter 5.5 of Division 21 of the Public Resources Code: “The State Coastal Conservancy hereby authorizes disbursement of an amount not to exceed nine million seven hundred fifty thousand dollars ($9,750,000) to The Wildlands Conservancy for acquisition of approximately 1,390 acres along the Santa Margarita River, as shown in Exhibit 1, for conservation and recreation purposes. This authorization is subject to the following conditions: 1. Prior to disbursement of any funds for acquisition of the property, The Wildlands Conservancy shall submit for the review and approval of the Executive Officer of the Conservancy: a) all relevant acquisition documents, including the appraisal, agreement of purchase and sale, escrow instructions, deeds, and documents of title; b) a baseline conditions report; c) a monitoring and reporting plan; and d) evidence that sufficient funds are available to complete the acquisition. 2. The Wildlands Conservancy shall not pay more than fair market value for the property acquired pursuant to this authorization, as established in an appraisal approved by the Executive Officer. -

Attachment B-4 San Diego RWQCB Basin Plan Beneficial Uses

Attachment B-4 San Diego RWQCB Basin Plan Beneficial Uses Regulatory_Issues_Trends.doc CHAPTER 2 BENEFICIAL USES INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................1 BENEFICIAL USES ..........................................................................................................................1 BENEFICIAL USE DESIGNATION UNDER THE PORTER-COLOGNE WATER QUALITY CONTROL ACT ..1 BENEFICIAL USE DESIGNATION UNDER THE CLEAN WATER ACT .................................................2 BENEFICIAL USE DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................3 EXISTING AND POTENTIAL BENEFICIAL USES ..................................................................................7 BENEFICIAL USES FOR SPECIFIC WATER BODIES ........................................................................8 DESIGNATION OF RARE BENEFICIAL USE ...................................................................................8 DESIGNATION OF COLD FRESHWATER HABITAT BENEFICIAL USE ...............................................9 DESIGNATION OF SPAWNING, REPRODUCTION, AND/ OR EARLY DEVELOPMENT (SPWN) BENEFICIAL USE ...................................................................................................11 SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER POLICY ..................................................................................11 EXCEPTIONS TO THE "SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER" POLICY................................................11 -

San Bernardino County, California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPAN~ MAP MF-1493-A UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IIINE1lAL RESOURCE POTBM"nAL OP THE BIGHORN MOUNTAINS WU.DERNJmS STUDY AREA (CDCA-217), SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SUMMARY REPORT By Miathan C. Matti, Brett P. Cox, Ecblrdo A. Rodriguez, CUrtis M. Obi, Robert E. Powell, Margaret E. Hinkle, and Andrew Griscom U.S. Geological Survey and Charles Sabine and Gary J. Cwick U.S. Bureau of Mines STUDIES RELATED TO WU.DERNESS Bureau of Land Management Wilderness Study Areas The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (Public Law 94-579, October 21, 1976) requires the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines to conduct mineral surveys in certain areas to determine their mineral resource potential. Results must be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report presents the results of a mineral survey of the Bighorn Mountains Wilderness Study Area (CDCA-217), California Desert Conservation Area, San Bernardino County, California. SUMMARY Geological, geochemical, and geophysical evidence, together with a review of historical mining and prospecting activities, suggests that most of the Bighorn Mountains Wilderness Study Area has low potential for the discovery of all types of mineral and energy resources-including precious and base metals, building stone and aggregate, fossil fuels, radioactive-mineral resources, . and geothermal resources. Low-grade mineralization has been documented in one small area near Rattlesnake Canyon, and this area has low to moderate potential for future small-scale exploration and development of precious and base metals. Thorium and uranium enrichment have been documented in two small areas in the eastern part of the wilderness study area; these two areas have low to moderate potential for future small-scale exploration and development of radioactive-mineral resources. -

Inland Empire Industrial Market

RESEARCH Q1 2021 Inland Empire Industrial Market Vacancy is in the Low 2s, a First for the Market Robust leasing activity from the last nine months of 2020 • Market Analysis carried over into early 2021. VACANCY AND ASKING RENT • Vacancy is at a record low, asking rent at a new high and 5% $0.75 developers are racing to break ground on new product. 4% $0.65 • Construction activity was up 36.2% from year-end 2020. 3% • Quarterly net absorption was substantially higher than the 2% $0.55 20-year average of 4.0 million square feet. Most of this 1% quarter’s activity came from the West. 0% $0.45 • Walmart, Amazon, 4PX Worldwide Express, Elogistic, 1Q16 1Q17 1Q18 1Q19 1Q20 1Q21 Comptree and Kenco Logistics all signed leases in excess of Average Asking Rent (per SF/NNN) Vacancy (%) 400,000 square feet. NET ABSORPTION, CONSTRUCTION DELIVERIES AND VACANCY • U.S. consumer e-commerce sales in 2020 were up 32.3% 12 5% from 2019. Expect more fulfillment centers. 4% 9 • Loaded inbound volume at the ports in the first two months 3% of 2021 was up 27.8% from the same period in 2020. 6 2% • Many U.S. distributors frontloaded imports before the start SF (in millions) 3 1% of Lunar New Year, a time when factories in China close for up to three weeks. 0 0% 1Q16 1Q17 1Q18 1Q19 1Q20 1Q21 • Gridlock: Maersk cited average vessel wait times of seven Net Absorption (SF) Deliveries (SF) Vacancy (%) to 15 days in Los Angeles-Long Beach by mid-March. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Southern California

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Southern California Climate and Vegetation Over the Past 125,000 Years from Lake Sequences in the San Bernardino Mountains A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Katherine Colby Glover 2016 © Copyright by Katherine Colby Glover 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Southern California Climate and Vegetation Over the Past 125,000 Years from Lake Sequences in the San Bernardino Mountains by Katherine Colby Glover Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Glen Michael MacDonald, Chair Long sediment records from offshore and terrestrial basins in California show a history of vegetation and climatic change since the last interglacial (130,000 years BP). Vegetation sensitive to temperature and hydroclimatic change tended to be basin-specific, though the expansion of shrubs and herbs universally signalled arid conditions, and landscpe conversion to steppe. Multi-proxy analyses were conducted on two cores from the Big Bear Valley in the San Bernardino Mountains to reconstruct a 125,000-year history for alpine southern California, at the transition between mediterranean alpine forest and Mojave desert. Age control was based upon radiocarbon and luminescence dating. Loss-on-ignition, magnetic susceptibility, grain size, x-ray fluorescence, pollen, biogenic silica, and charcoal analyses showed that the paleoclimate of the San Bernardino Mountains was highly subject to globally pervasive forcing mechanisms that register in northern hemispheric oceans. Primary productivity in Baldwin Lake during most of its ii history showed a strong correlation to historic fluctuations in local summer solar radiation values. -

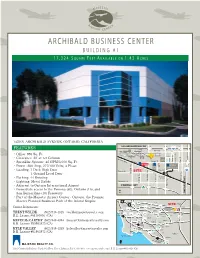

Archibald Business Center Building #1 1 7 , 3 2 4 S Q U a R E F E E T a Vailable on 1

ARCHIBALD BUSINESS CENTER BUILDING #1 1 7 , 3 2 4 S Q U A R E F E E T A VAILABLE ON 1 . 4 3 A CRES 1420 S. ARCHIBALD AVENUE, ONTARIO, CALIFORNIA SAN BERNARDINO FWY FEATURES 10 Ontario Airport Dr. International • Office: 993 Sq. Ft. Airport La Salle St. • Clearance: 22’ at 1st Column Mission U.P.R.R. UPS Carnegie Ave. Carnegie Dupont St. Dupont Commerce Pkwy. Commerce • Sprinkler System: .45 GPM/3,000 Sq. Ft. Blvd. Jurupa St. Fayette La . e ARCHIBALD UPS v CALIFORNIA • Power: 800 Amp, 277/480 Volts, 3 Phase A HOFER COMMERCE CENTER . RANCH • Loading: 1 Dock High Door Francis St. 15 Francis St. Ave Vineyard M e. 1 Ground Level Door v A Ave. Metrolink • Parking: 44 Existing Station Milliken Ave. Archibald Ave. Turner • Lighting: Metal Halide Philadelpia St. Hellman • Adjacent to Ontario International Airport POMONA FWY Haven 60 • Immediate access to the Pomona (60), Ontario (15), and San Bernardino (10) Freeways N ONTARIO FWY • Part of the Majestic Airport Center - Ontario, the Premier Master Planned Business Park of the Inland Empire 101 134 AZUSA RANCHO PASADENA CUCAMONGA LOS 101 5 ANGELES SAN DIMAS 210 FONTANA ContactFEATURES Information: 10 ONTARIO 10 INTERNATIONAL CITY OF AIRPORT INDUSTRY 57 TRENT WYLDE (562) 948-4315 [email protected] LOS ANGELES 60 ONTARIO INTL. 405 110 605 DIAMOND BAR MIRA 710 WHITTIER LOMA AIRPORT 71 CHINO R.E. License #01180856 (CA) 105 57 CHINO HILLS 15 SANTA FE BREA 5 SPRINGS YORBA LINDA KEVIN McCARTHY (562) 948-4394 [email protected] CORONA 91 FULLERTON PLACENTIA LONG 91 R.E. -

Title 9: Public Property, Public Works and Building Regulations

TITLE 9: PUBLIC PROPERTY, PUBLIC WORKS AND BUILDING REGULATIONS Chapter Section Subject Page 9.05 Beaches and Piers 9.05.005 Definitions ................................................................ 01 9.05.010 Lifeguards ................................................................ 02 9.05.015 Beachcombing ......................................................... 02 9.05.020 Beach Closure ......................................................... 02 9.05.025 Encroachments ........................................................ 02 9.05.030 Public Clothing Changes .......................................... 02 9.05.035 Littering (Ord 1538 - 2005) ................................................ 03 9.05.040 Sand Removal ......................................................... 03 9.05.045 Aquatic Activities ...................................................... 03 9.05.050 Athletic Activities at Seal Way .................................. 03 9.05.055 Fires ......................................................................... 03 9.05.060 Smoking on Pier or Beach (Ord 1538 - 2005) ................... 04 9.05.065 Fishing ..................................................................... 04 9.05.070 Climbing, Diving and Jumping .................................. 04 9.05.075 Defacement of Pier .................................................. 04 9.05.080 Removal of Mussels ................................................. 04 9.05.085 Commercial Activities on Beach or Pier ................... 05 9.05.090 Vehicles and Animals .............................................. -

III. General Description of Environmental Setting Acres, Or Approximately 19 Percent of the City’S Area

III. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING A. Overview of Environmental Setting Section 15130 of the State CEQA Guidelines requires an EIR to include a discussion of the cumulative impacts of a proposed project when the incremental effects of a project are cumulatively considerable. Cumulative impacts are defined as impacts that result from the combination of the proposed project evaluated in the EIR combined with other projects causing related impacts. Cumulatively considerable means that the incremental effects of an individual project are considerable when viewed in connection with the effects of past projects, the effects of other current projects, and the effects of probable future projects. Section 15125 (c) of the State CEQA Guidelines requires an EIR to include a discussion on the regional setting that the project site is located within. Detailed environmental setting descriptions are contained in each respective section, as presented in Chapter IV of this Draft EIR. B. Project Location The City of Ontario (City) is in the southwestern corner of San Bernardino County and is surrounded by the Cities of Chino and Montclair, and unincorporated areas of San Bernardino County to the west; the Cities of Upland and Rancho Cucamonga to the north; the City of Fontana and unincorporated land in San Bernardino County to the east; the Cities of Eastvale and Jurupa Valley to the east and south. The City is in the central part of the Upper Santa Ana River Valley. This portion of the valley is bounded by the San Gabriel Mountains to the north; the Chino Hills, Puente Hills, and San Jose Hills to the west; the Santa Ana River to the south; and Lytle Creek Wash on the east. -

Santa Ana River Watermaster

SANTA ANA RIVER WATERMASTER ORANGE COUNTY WATER DISTRICT v. CITY OF CHINO, et al. CASE NO. 117628--COUNTY OF ORANGE WATERMASTER MAILING ADDRESS P. Joseph Grindstaff c/oSBVMWD Douglas D. Headrick 380 East Vanderbilt Way Roy L. Herndon San Bernardino CA 92408-3593 Michael R. Markus Telephone (909) 387-9200 John V. Rossi FAX (909) 387-9247 April 30, 2015 To: Clerk of Superior Court of Orange County and all Parties Re: Watermaster Report for Water Year October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Ladies and Gentlemen: We have the honor of submitting herewith the Forty-Fourth Annual Report of the Santa Ana River Watermaster. The supporting Basic Data Appendices are bound separately. The principal findings of the Watermaster for the Water Year 2013-14 are as follows: At Prado 1 Measured Outflow at Prado 86,486 acre-feet 2 Base Flow at Prado 63,536 acre-feet 3 Annual Weighted TDS in Base and Storm Flows 582 mg/L 4 Annual Adjusted Base Flow 69,784 acre-feet 5 Cumulative Adjusted Base Flow 5,282,666 acre-feet 6 Other Credits (Debits) 0 acre-feet 7 Cumulative Entitlement of OCWD 1,848,000 acre-feet 8 Cumulative Credit 3,474,674 acre-feet 9 One-Third of Cumulative Debit 0 acre-feet 10 Minimum Required Base Flow in 2013-14 34,000 acre-feet April 30, 2015 Page 2 of 2 At Riverside Narrows 1 Base Flow at Riverside Narrows 32, 313 acre-feet 2 Annual Weighted TDS in Base Flow 646 mg/L 3 Annual Adjusted Base Flow 32,313 acre-feet 4 Cumulative Adjusted Base Flow 1,958,244 acre-feet 5 Cumulative Entitlement of IEUA and WMWD 671,000 acre-feet 6 Cumulative Credit 1,287,244 acre-feet 7 One-Third of Cumulative Debit 0 acre-feet 8 Minimum Required Base Flow in 2013-14 12,420 acre-feet Based on these findings, the Watermaster concludes that there was full compliance with the provisions of the Stipulated Judgment in 2013-14. -

Chino Hills Historical Society Press Release

Chino Hills Historical Society Press Release Date: July 27, 2017 Contact: Denise Cattern, CHHS President (909) 597-6449 Chino Hills Historical Society Presents: “A Look Back at Antonio María Lugo and the Early Years of the Rancho Santa Ana del Chino” Monday, September 18th The Chino Hills Historical Society will host a presentation by Chino Hills resident and historian Paul R. Spitzzeri at 7:00 p.m. on Monday, September 18th at the Chino Hills Community Center, 14259 Peyton Drive. Spitzzeri will share the history of Antonio María Lugo and the early years of the Rancho Santa Ana del Chino. According to Spitzzeri, Antonio María Lugo (1775-1860), born near Monterey, Mexico just six years after the Spanish first settled California, was one of the most prominent and remarkable persons in greater Los Angeles during his lifetime. A soldier in the Spanish Army during his younger years, Lugo was granted the Rancho San Antonio, encompassing nearly 30,000 acres southeast of Los Angeles. Later, he and his family acquired the Rancho San Bernardino and Rancho Santa Ana del Chino, the latter including today’s cities of Chino and Chino Hills. “Lugo was torn by the loss of California to the Americans during a war that included the Battle of Chino, which was fought on what is now Boys Republic,” said Mr. Spitzzeri, “He was known for his forthright personality, hospitality, and strength of character.” Mr. Spitzzeri has lived in Chino Hills for 20 years. He is the Museum Director at the Workman and Temple Family Homestead Museum in the City of Industry, where he has worked since 1988. -

Draft Trails Master Inventory

City of Corona Trails Master Inventory Draft May 2019 Acknowledgements City of Corona Joanne Coletta, Community Development Director Nelson Nelson, Public Works Director David Montgomery-Scott, Library & Recreation Services Director Trails Subcommittee KTUA John Holloway, Retired Principal Alex Samarin, GIS Manager, Project Manager Jacob Leon, Associate, Outreach Coordinator II | City of Corona Trails Master Inventory DRAFT Contents Figures Figure 1-1: Study Area ........................................................................................ 3 Introduction 1 Figure 2-1: Population Density Map ............................................................. 9 01 Study Area ......................................................................................... 2 Figure 2-2: Land Use Map ............................................................................. 10 Scope and Vision ............................................................................. 2 Figure 2-3: Existing and Previously Proposed Bike Facilities ............. 11 Planning Context ............................................................................. 6 Figure 2-4: Five Minute Trailhead Drivesheds .........................................12 Figure 2-5: Ten Minute Trailhead Drivesheds ..........................................13 Figure 3-1: Online Map Comments ........................................................... 20 Existing Conditions 9 Figure 3-2: Trailhead Community Comments........................................23 02 Existing Conditions Overview