What Do We Know About Housing Supply? the Case of Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hang Lung Properties Wait with Patience

30 May 2018 Hong Kong EQUITIES Hang Lung Properties 101 HK Neutral Wait with patience Price (at 06:50, 30 May 2018 GMT) HK$17.96 Valuation HK$ 33.32 Key points - DCF (WACC 7.7%, beta 1.1, ERP 6.0%, RFR 1.5%) Acquired a land king in Hangzhou with good growth potential 12-month target HK$ 18.43 Large cost leads to slim yield, and long investment period impacts NAV Upside/Downside % +2.6 12-month TSR % +6.8 Benefit from strong retail sales but renovations temporarily hurt Volatility Index Low GICS sector Real Estate Event Market cap HK$m 80,779 We believe the acquisition of the new land king gives the company a good Market cap US$m 10,296 opportunity to ride on the strong retail growth and development of a quasi tier- Free float % 42 1 city. We believe the Hangzhou mall can charge the highest unit rental at 30-day avg turnover US$m 7.8 Rmb700 psm/mth among Hang Lung’s mainland shopping malls except for Number shares on issue m 4,498 Shanghai projects, which are charging more than Rmb1,500. However, as it will take six years to complete in 2024 and total investment cost could be as Investment fundamentals high as Rmb19bn with a 4-5% gross yield, the acquisition should negatively Year end 31 Dec 2017A 2018E 2019E 2020E impact the earnings, cash flow and NAV in recent years. Some previous Revenue m 11,199 10,721 11,107 9,449 EBIT m 7,330 7,452 7,704 6,020 projects have had a long development cycle for five to nine years and EBIT growth % -11.8 1.7 3.4 -21.9 experienced disappointing rentals. -

Hang Lung Properties Version 9 | Bloomberg: 101 HK EQUITY | Reuters: 101.HK Refer to Important Disclosures at the End of This Report

China / Hong Kong Company Guide Hang Lung Properties Version 9 | Bloomberg: 101 HK EQUITY | Reuters: 101.HK Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 31 Jul 2019 BUY Retail sales growth gathering Last Traded Price ( 30 Jul 2019):HK$18.64 (HSI : 28,147) momentum Price Target 12-mth: HK$22.38 (20.1% upside) (Prev HK$20.35) BUY with HK$22.38 TP. The stock is trading at a 49% discount to Analyst our estimated current NAV and offers an attractive dividend yield Jeff YAU CFA, +852 36684180 [email protected] of 4.0% for FY19. Stellar tenants’ sales growth at its retail malls in Ian CHUI +852 36684174 [email protected] Jason LAM +852 36684179 [email protected] China augurs well for reversionary growth. Portfolio expansion and asset enhancement initiatives should provide additional What’s New momentum to drive rental income, offering better earnings quality • Improving retail tenants’ sales to underpin and in turn providing share price upside. HLP is among our preferred landlords. BUY with HK$22.38 TP. reversionary growth Portfolio expansion to lift rental income. The progressive opening • New properties to spice up rental earnings of new properties in Kunming, Wuhan, Wuxi, and Shenyang in • BUY with HK$22.38 TP 2019-20 should give an additional boost to Hang Lung Properties’ recurrent earnings growth, and its ability to raise dividends. Pre- leasing at Spring City 66 in Kunming is progressing smoothly, with Price Relative 88% of retail space already pre-committed. This mall is scheduled to open for business in late Aug. -

STOXX Hong Kong All Shares 50 Last Updated: 01.12.2016

STOXX Hong Kong All Shares 50 Last Updated: 01.12.2016 Rank Rank (PREVIOUS ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) ) KYG875721634 BMMV2K8 0700.HK B01CT3 Tencent Holdings Ltd. CN HKD Y 128.4 1 1 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 69.3 2 2 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 60.3 3 4 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 57.5 4 3 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 37.7 5 5 CNE1000001Z5 B154564 3988.HK CN0032 BANK OF CHINA 'H' CN HKD Y 32.6 6 7 KYG217651051 BW9P816 0001.HK 619027 CK HUTCHISON HOLDINGS HK HKD Y 32.0 7 6 HK0388045442 6267359 0388.HK 626735 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing HK HKD Y 28.5 8 8 CNE1000003X6 B01FLR7 2318.HK CN0076 PING AN INSUR GP CO. OF CN 'H' CN HKD Y 26.5 9 9 CNE1000002L3 6718976 2628.HK CN0043 China Life Insurance Co 'H' CN HKD Y 20.4 10 15 HK0016000132 6859927 0016.HK 685992 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd. HK HKD Y 19.4 11 10 HK0883013259 B00G0S5 0883.HK 617994 CNOOC Ltd. CN HKD Y 18.9 12 12 HK0002007356 6097017 0002.HK 619091 CLP Holdings Ltd. HK HKD Y 18.3 13 13 KYG2103F1019 BWX52N2 1113.HK HK50CI CK Property Holdings HK HKD Y 17.9 14 11 CNE1000002Q2 6291819 0386.HK CN0098 China Petroleum & Chemical 'H' CN HKD Y 16.8 15 14 HK0688002218 6192150 0688.HK 619215 China Overseas Land & Investme CN HKD Y 14.8 16 16 HK0823032773 B0PB4M7 0823.HK B0PB4M Link Real Estate Investment Tr HK HKD Y 14.6 17 17 CNE1000003W8 6226576 0857.HK CN0065 PetroChina Co Ltd 'H' CN HKD Y 13.5 18 19 HK0003000038 6436557 0003.HK 643655 Hong Kong & China Gas Co. -

Pair Trade Weekly

Hong Kong / China Pair Trade Weekly DBS Group Research . Equity 12 January 2010 Seven Pair Ideas HSI: 22,412 Pairs for the week ANALYST New Pair Derek Cheung· (852) 2971 1703 · • Long - Shimao Property (813 HK); [email protected] Short - Sino-Ocean Land (3377 HK) Alice Hui, CFA · (852) 2971 1960 · Maintain [email protected] • Long - Denway Motors (203 HK); Carol Wu · (852) 2863 8841· [email protected] Short - Geely Automobile (175 HK) • Long - Dah Sing Financial (440 HK); Danielle Wang · (852) 2820 4915· danielle_wang @hk.dbsvickers.com Short - Wing Hang (302 HK) • Long - Hang Lung Group (10 HK); Dennis Lam · (852) 2971 1922· [email protected] Short - Hang Lung Properties (101 HK) Gideon Lo, CFA · (852) 2863 8880 · • Long - Sinopec (386 HK); [email protected] Short - CNOOC (883 HK) Jasmine Lai · (852) 2971 1926 · • Long - China Telecom (728 HK); [email protected] Short - China Unicom (762 HK) Jeff Yau CFA· (852) 2820 4912 · • Long - Shenzhen Expressway (548 HK); [email protected] Short - Hopewell Highway Infrastruct (737 HK) Mavis Hui · (852) 2863 8879 · [email protected] Patricia Yeung · (852) 2863 8908 · [email protected] Prices used as of 11 January 2010 Patrick Xu (65) 6398 7957 [email protected] Paul Yong CFA +86 21 6888 3372 [email protected] Rachel Miu · (852) 2863 8843· [email protected] Steven Liu, CFA (852) 2971 1780 [email protected] Titus Wu · (86 21) 6888 3360 · [email protected] In Singapore, this research report or research analyses may only be distributed to Institutional Investors, Expert Investors or Accredited Investors as defined in the Securities and Futures Act, Chapter 289 of Singapore. -

Hang Lung Properties (0101.HK) Above Expectations: Plaza 66

July 27, 2017 EARNINGS REVIEW Hang Lung Properties (0101.HK) Neutral Equity Research Above expectations: Plaza 66 growing but others still stabilizing What surprised us Investment Profile Hang Lung Properties (HLP) reported 1H 2017 underlying profit of Low High HK$3,040mn, down 4% yoy on higher finance expense, but ahead of our Growth Growth Returns * Returns * forecasts on faster property sales bookings and gross margins at 65%, 7pp Multiple Multiple higher yoy. Headline overall rental revenue was down 2% yoy with China - Volatility Volatility 4% yoy and HK 1% yoy. However, excluding currency impact, China rental Percentile 20th 40th 60th 80th 100th was indeed up 1% in RMB terms, while that from HK was up 3% excluding Hang Lung Properties (0101.HK) AEI. Interim DPS was flat yoy at HK¢17. BVPS was up 3% hoh to HK$28.9, Hong Kong Property Peer Group Average * Returns = Return on Capital For a complete description of the investment with HK$1bn positive revaluation for IPs in HK being partly offset by minus profile measures please refer to the HK$0.3bn for those in China. disclosure section of this document. Key data Current Price (HK$) 19.32 What to do with the stock 12 month price target (HK$) 21.80 While management characterized the operating environment for Chinese Market cap (HK$ mn / US$ mn) 86,727.5 / 11,102.6 Foreign ownership (%) -- cities in which they operate as challenging, it was clear that growth resumed in Shanghai with Plaza 66 as tenant sales grew 20% yoy 12/16 12/17E 12/18E 12/19E EPS (HK$) New 1.38 1.20 1.07 1.04 excluding AEI. -

(1969 Nov)The Index Includes the Largest and Most Liquid Stocks Listed in Hong Kong

Hang Seng Index | Index Constituents Analysis | Thomson Reuters Eikon 15-Aug-2016 08:29 Index Constituents Analysis - (1969 Nov)The index includes the largest and most liquid stocks listed in Hong Kong Report: Index Sector - 10% capping is applied to avoid single stock domination 1 - 50 of 50 - Four sector sub-indexes are also available Sub-indexes: (see table below) Sector Market Cap - Finance; Utility; Properties; Commerce & Industry - represent about 58% of the capitalisation of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange Sector - TRBC USD Percent Financials 1,477,418,432,940.93 61.67 Energy 388,919,496,168.72 6.76 Telecommunications Services 287,167,406,479.74 8.94 Technology 236,946,991,592.06 10.45 Utilities 103,353,908,003.74 6.02 Consumer Cyclicals 55,503,276,570.23 2.48 Industrials 50,240,279,801.09 1.76 Consumer Non-Cyclicals 31,116,477,725.85 1.91 Total -- 100.00% Name RIC Weight % Mcap(USD) Financials 61.67 1,477,418,432,940.93 HSBC Holdings PLC 0005.HK 9.73 140,216,593,956.09 AIA Group Ltd 1299.HK 8.08 76,668,842,578.97 China Construction Bank Corp 0939.HK 6.51 184,114,982,866.54 Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd 1398.HK 4.80 236,531,316,123.03 Bank of China Ltd 3988.HK 3.67 153,437,411,763.61 CK Hutchison Holdings Ltd 0001.HK 3.51 47,648,815,932.83 Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd 0388.HK 3.10 30,937,262,168.73 Ping An Insurance Group Co of China Ltd 2318.HK 2.77 92,179,858,049.49 Sun Hung Kai Properties Ltd 0016.HK 2.19 41,545,598,968.05 Cheung Kong Property Holdings Ltd 1113.HK 2.01 27,194,797,037.17 China Life Insurance -

Survey on the Hang Seng Index (HSI) Constituents’ Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)

Survey on the Hang Seng Index (HSI) Constituents’ Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Executive Summary and Policy Suggestions Preface Oxfam Hong Kong (OHK) has been promoting corporate social responsibility (CSR) for over a decade, as private sector behaviour has a significant impact on social and economic development. Companies, while making profit from the society, should equally be committed to their employees, consumers, the community and environment in which they operate. CSR is not simply ‘doing good’ or mere philanthropy. It involves integrating Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) policies and practices into corporate strategy and business operations for the benefit of all. Companies should play a more active role in supporting the community at large, and help underprivileged people benefit from economic development, thus reducing poverty in the long run. International trends are showing the importance of CSR. Since 2012, for example, major stock exchanges around the world ‒ including the London Stock Exchange, Nasdaq, New York Stock Exchange and Deutsche Börse AG ‒ have become partners of the Sustainable Stock Exchange (SSE) initiative. The SSE’s1 recent guidelines suggest that CSR should encompass the broad set of ESG considerations that can impact a company’s ability to execute its business strategy and create value. As people living in poverty can benefit from economic development through enhanced CSR, OHK has been promoting the integration of ESG into corporate policies and business operations since 2004. OHK conducted two pioneering studies in 2008 and 2009 to study the CSR performance of the Hang Seng Index (HSI) constituents by looking at the implementation of their CSR initiatives. -

Hang Lung Green Loan

For immediate release Hang Lung Strengthens Its Commitment to Sustainability with Inaugural Green Loan from OCBC Bank (Hong Kong/Singapore, December 23, 2019) Hang Lung Properties Limited (“Hang Lung”, HKSE Stock Code: 00101), a leading property developer headquartered in Hong Kong, has secured a HK$1 billion green loan facility from OCBC Hong Kong Branch. This is Hang Lung’s maiden green loan, the proceeds of which will be used to finance commercial property development projects in mainland China, which have received gold certifications or pre-certifications issued by the U.S. Green Building Council of Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), promoting sustainable development in the real estate industry on the Mainland. In upholding its sustainability principle Build to Own, Build to Last, Hang Lung is committed to putting sustainable development at the heart of its core values as they create architectural landmarks in cities with great potential. The company has been selected as an index component of the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices in the Asia Pacific Index for two consecutive years since 2017, recognizing its achievements in corporate sustainability. This green loan is issued under Hang Lung’s Green Finance Framework, which outlines the criteria and guidelines that will be used in the allocation of the green finance proceeds in line with the 2018 Green Bond Principles and 2018 Green Loan Principles. The framework has been reviewed and confirmed by Sustainalytics, a global provider of ESG research and ratings, to be credible and impactful. For OCBC Bank, which recently topped two regional sustainable finance league tables, this green loan is the latest milestone towards its target of achieving a S$10 billion sustainable finance portfolio by 2022. -

Investor Presentation

The Link Real Estate Investment Trust Investor Presentation January 2012 P.1 Disclaimer This document has been prepared by The Link Management Limited in its capacity as the Manager (the ―Manager‖) of The Link Real Estate Investment Trust (―The Link REIT‖) solely for use at the presentations held in this meeting and may not be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or the press or other media. Without the prior written approval of the Manager, neither this document nor any copy may be taken or transmitted into or distributed, directly or indirectly, in the United States or to any U.S. person (within the meaning of Regulation S under the United States Securities Act of 1933, as amended). Neither this document nor any copy may be taken or transmitted into or distributed or redistributed in Canada or to the resident thereof. The distribution of this document in other jurisdictions may be restricted by law and persons into whose possession this document comes should inform themselves about, and observe any such restrictions. Any failure to comply with these restrictions may constitute a violation of applicable securities laws. All information and data are provided for information purposes only. All opinions expressed by The Link REIT herein are based on information available as of the date hereof and are subject to change without notice. The information contained in this document is not intended to provide, and you may not rely on this document as providing, a complete or comprehensive analysis of The Link REIT’s financial or trading position or prospects. The past performance of The Link REIT is not necessary indicative of the future performance of The Link REIT and nothing contained in this document is, or shall be relied on, as a promise or forecast as to the future. -

Hang Lung Properties (0101.HK) Positive Rental Reversions and Progressive Completions to Drive Growth;

31 January 2019 | 6:15AM HKT Hang Lung Properties (0101.HK) Positive rental reversions and progressive completions to drive growth; Buy Reiterate Buy 0101.HK 12m Price Target: HK$20.00 Price: HK$16.84 Upside: 18.8% Justin Kwok, CFA +852-2978-0481 | [email protected] Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. We reiterate our Buy rating on Hang Lung Properties (HLP) as we Colin Yao +852-2978-1474 | [email protected] think both FY18 results and management guidance provided at its Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. briefing reaffirm our view that its resilient fundamentals and pathway to earnings growth are underappreciated by the market based on current valuations due to concerns about the macro environment and the Hangzhou project acquisition last May. Key Data __________________________________ Management is optimistic on China rental operations amid Market cap: HK$75.6bn / $9.6bn Enterprise value: HK$104.1bn / $13.3bn uncertain macro backdrop 3m ADTV: HK$63.7mn / $8.1mn Hong Kong n China rental growth pace accelerated into 2H2018 Hong Kong Property M&A Rank: 3 o Amid uncertain macro backdrop, HLP’s 2H18’s rental GS Forecast ________________________________ revenue growth in China accelerated to 6% yoy on RMB 12/18 12/19E 12/20E 12/21E Revenue (HK$ mn) New 9,408.0 9,637.0 10,523.5 11,707.6 basis, faster than 1H18’s 2%, driven by better Revenue (HK$ mn) Old 9,356.8 9,920.1 9,985.5 -- EBITDA (HK$ mn) 6,227.0 6,454.8 6,951.1 7,673.3 performance across both malls in and out of Shanghai EPS (HK$) New 1.80 0.93 0.99 1.12 (with the exception their Tianjin Riverside 66 mall). -

Hang Lung Properties (101 HK)

Hong Kong Real Estate 30 January 2018 Hang Lung Properties (101 HK) Target price: HKD25.10 (from HKD23.70) Share price (30 Jan): HKD20.10 | Up/downside: +24.9% Foundation for an upturn looks to be coming into place Financial figures yet to fully reflect operating progress seen in 2017 Jonas Kan, CFA (852) 2848 4439 Plaza 66 is strong and it may have found the way out for tier-2 cities [email protected] Reiterating our Buy (1) rating; lifting TP to HKD25.10 What's new: Hang Lung Properties’ 2017 underlying net profit fell by 13% Forecast revisions (%) YoY to HKD5,530m, mainly on a 36% YoY decline in property sales profit. Year to 31 Dec 18E 19E 20E We see HLP’s rental business and earnings mix as currently in transition, Revenue change 8.1 15.2 n.a. Net profit change - 10.8 n.a. with aggregate financial results yet to reflect more significant fundamental Core EPS (FD) change - 10.8 n.a. improvement in its leasing business in both China and Hong Kong. Source: Daiwa forecasts What's the impact: Actual performance was better than what the figures Share price performance may suggest, given that HLP’s aggregate results were affected by quite a (HKD) (%) few transitional factors such as AEIs and tenants repositioning. Our read is 22.0 105 that HLP has been very active in revamping its operations during the soft 20.8 96 market in the past few years and that important progress has been made – 19.5 88 we think some initial signs of turnaround had already emerged in its 1H17 18.3 79 17.0 70 results (please see our note Initial turnaround looks to be underway from Feb-17 May-17 Aug-17 Nov-17 28 July 2017) and our read is that such trend has continued into 2H17. -

Hang Lung Properties Limited 2020 Annual Results

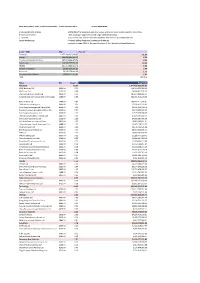

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. HANG LUNG PROPERTIES LIMITED (Incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability) (Stock Code: 00101) 2020 ANNUAL RESULTS 2020 Annual Results CONTENTS Page Financial Highlights 1 Review of Operations 2 Consolidated Financial Statements 19 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 23 Other Information 34 Glossary 36 2020 Annual Results FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS in HK$ Million (unless otherwise stated) RESULTS 2020 2019 Property Property Property Property Leasing Sales Total Leasing Sales Total Revenue 8,911 62 8,973 8,556 296 8,852 - Mainland China 5,277 - 5,277 4,544 - 4,544 - Hong Kong 3,634 62 3,696 4,012 296 4,308 Operating profit 6,437 44 6,481 6,325 162 6,487 - Mainland China 3,468 (8) 3,460 2,938 (2) 2,936 - Hong Kong 2,969 52 3,021 3,387 164 3,551 Underlying net profit attributable to shareholders 4,164 37 4,201 4,338 136 4,474 Net (decrease)/increase in fair value of properties attributable to shareholders (6,772) - (6,772) 1,698 - 1,698 Net (loss)/profit attributable to shareholders (2,608) 37 (2,571) 6,036 136 6,172 At December 31, At December 31, 2020 2019 Shareholders’ equity 138,295 138,669 Net assets attributable to shareholders per share (HK$) $30.7 $30.8 Earnings