The Collateral Mortgage: Logic and Experience, 49 La

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortgage-Backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations

Mortgage-backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations: Prudent CRA INVESTMENT Opportunities by Andrew Kelman,Director, National Business Development M Securities Sales and Trading Group, Freddie Mac Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) have Here is how MBSs work. Lenders because of their stronger guarantees, become a popular vehicle for finan- originate mortgages and provide better liquidity and more favorable cial institutions looking for investment groups of similar mortgage loans to capital treatment. Accordingly, this opportunities in their communities. organizations like Freddie Mac and article will focus on agency MBSs. CRA officers and bank investment of- Fannie Mae, which then securitize The agency MBS issuer or servicer ficers appreciate the return and safety them. Originators use the cash they collects monthly payments from that MBSs provide and they are widely receive to provide additional mort- homeowners and “passes through” the available compared to other qualified gages in their communities. The re- principal and interest to investors. investments. sulting MBSs carry a guarantee of Thus, these pools are known as mort- Mortgage securities play a crucial timely payment of principal and inter- gage pass-throughs or participation role in housing finance in the U.S., est to the investor and are further certificates (PCs). Most MBSs are making financing available to home backed by the mortgaged properties backed by 30-year fixed-rate mort- buyers at lower costs and ensuring that themselves. Ginnie Mae securities are gages, but they can also be backed by funds are available throughout the backed by the full faith and credit of shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages or country. The MBS market is enormous the U.S. -

Secondary Mortgage Market

8-6 Legal Considerations - Real Estate Contracts - Financing Basic Appraisal Principles Other Sources of Funds Pension Funds and Insurance Companies Pension funds and insurance companies have recently had such growth that they have been looking for new outlets for their investments. They manage huge sums of money, and traditionally have invested in ultra-conservative instruments, such as government bonds. However, the booming economy of the 1990s, and corresponding budget surpluses for the federal government, left a shortage of treasury securities for these companies to buy. They had to find other secure investments, such as mortgages, to invest their assets. The higher yields available with Mortgage Backed Securities were also a plus. The typical mortgage- backed security will carry an interest rate of 1.00% or more above a government security. Pension funds and insurance companies will also provide direct funding for larger commercial and development loans, but will rarely loan for individual home mortgages. Pension funds are regulated by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (1974). Secondary Mortgage Market The secondary mortgage market buys and sells mortgages created in the primary mortgage market (the link to Wall Street). A valid mortgage is always assignable by the mortgagee, allowing assignment or sale of the rights in the mortgage to another. The mortgage company can sell the loan, the servicing, or both. If just the loan is sold without the servicing, the original lender will continue to collect payments, and the borrower will never know the loan was sold. If the lender sells the servicing, the company collecting the payments will change, but the terms of the loan will stay the same. -

{670031-4} 1 Collateral Assignment of Leases And

COLLATERAL ASSIGNMENT OF LEASES AND RENTS THIS COLLATERAL ASSIGNMENT OF LEASES AND RENTS (this “Assignment”) is entered into as of _________, 2021, by and between Yingling Aircraft, Inc., a Kansas corporation (“Assignor”); and INTRUST Bank, N.A., a national banking association (“Lender”). Recitals A. Wichita Airport Authority, Wichita, Kansas (“Lessor”) and LeaseCorp Financial, Inc., a Kansas corporation, entered into that certain Master Lease Agreement dated June 12, 2012, which was assigned by LeaseCorp Financial, Inc. to LeaseCorp Aviation, LLC, which was then assigned by LeaseCorp Aviation, LLC to Yingling Aircraft, Inc., as may be amended, all of which are incorporated herein by reference (together, “Master Lease 1”), covering certain aircraft hangar operation facilities located at the Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport, Wichita, Kansas, further described as Tract 1 on Exhibit “A” attached hereto and incorporated by reference, and any and all improvements now or hereafter located thereon (such land and improvements being herein referred to collectively as “Tract 1”). B. Wichita Airport Authority, Wichita, Kansas (“Lessor”) and LeaseCorp Aviation, LLC, a Kansas limited liability company, entered into that certain Master Lease Agreement dated October 14, 2014 and Supplemental Agreement No. 1 dated March 1, 2016, as may be amended, all of which are incorporated herein by reference (together, “Master Lease 2”), covering certain aircraft hangar operation facilities located at the Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport, Wichita, Kansas, further described as Tract 2 on Exhibit “A” attached hereto and incorporated by reference, and any and all improvements now or hereafter located thereon (such land and improvements being herein referred to collectively as “Tract 2”). -

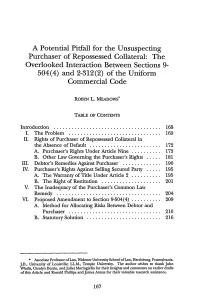

A Potential Pitfall for the Unsuspecting Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral

A Potential Pitfall for the Unsuspecting Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral: The Overlooked Interaction Between Sections 9- 504(4) and 2-312(2) of the Uniform Commercial Code ROBYN L. MEADOWS* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .................................... 168 I. The Problem . ............................... 169 II. Rights of Purchaser of Repossessed Collateral in the Absence of Default ........................ 172 A. Purchaser's Rights Under Article Nine .......... 173 B. Other Law Governing the Purchaser's Rights ..... 181 III. Debtor's Remedies Against Purchaser ............. 190 IV. Purchaser's Rights Against Selling Secured Party ..... 195 A. The Warranty of Title Under Article 2 .......... 195 B. The Right of Restitution .................... 201 V. The Inadequacy of the Purchaser's Common Law Remedy . ................................... 204 VI. Proposed Amendment to Section 9-504(4) .......... 209 A. Method for Allocating Risks Between Debtor and Purchaser ............................... 210 B. Statutory Solution ......................... 216 * Associate Professor of Law, Widener University School of Law, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. J.D., University of Louisville; LL.M., Temple University. The author wishes to thank John Wiadis, Carolyn Dessin, andJuliet Moringiello for their insights and comments on earlier drafts of this Article and Ronald Phillips and James Annas for their valuable research assistance. THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 44:167 INTRODUCTION Under the provisions of the Uniform Commercial Code (the Code), -

Home Equity Loans - FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Home Equity Loans - FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS WHAT IS A HOME EQUITY LOAN? Home equity loans fall under the provisions of Section 50(a)(6), Article XVI, of the Texas Constitution. A home equity loan can be for any legal purpose which uses the equity (the difference between the home’s value and any outstanding debts against the home) in a member’s home for collateral. For home equity lending, Texas law restricts the total amount of all loans secured by the homestead to a maximum of 80% of the home’s value. Texas home equity loans can be a closed end loan with substantially equal payments over a fixed period of time, or an open end Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC). WHAT PROPERTIES CAN BE CONSIDERED? The property used for collateral must be a single-family, owner-occupied homestead property, located within the Austin Metropolitan Statistical Area (Travis, Williamson, Hays, Bastrop and Caldwell counties). Qualifying properties are defined as either urban or rural. Urban properties consist of not more than 10 acres of land with any improvements contained thereon, within the limits of a municipality or it’s extraterritorial jurisdiction, or a platted subdivision; AND served by police protection, paid or volunteer fire protection, and at least three of the following services provided by a municipality or under contract to a municipality: electric, natural gas, sewer, storm sewer, or water. Rural property shall consist of not more than 200 acres for a family (100 acres for a single, adult person not otherwise entitled to a homestead), with the improvements thereon. -

Foreclosing on Collateral That Includes Intangible Rights

Foreclosing on Collateral That Includes Intangible Rights JOHN I. KARESH* Table of Contents I. Introduction II. In Re Northwest Airlines Corporation 1. Court Held That Secured Party Could Not File a Proof of Claim Against Bankrupt Lessee Because Secured Party Had Not Foreclosed on Lease Rights 2. Comments on the Northwest Airlines Corporation Decision: (a) UCC Article 9 Actually Does Not Require Fore- closure for Secured Party to Enforce Assigned Lease Rights and Remedies (b) Practical Diculties in Requiring Foreclosure as a Condition to Enforcement by Secured Party of Assigned Lease Rights and Remedies III.Bremer Bank, National Association v. John Hancock Life Insurance Company et al. 1. Court Held that Early Steps Taken by Secured Party to Protect its Interests in Assigned Lease Constitute Enforcement of Remedies 2. Comments on the Bremer Decision: Why Foreclosure Was Necessary IV. Conclusion V. Appendix: Suggested Provisions to Avoid Issues Raised by the Northwest Case *John Karesh is a shareholder at Vedder Price P.C. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reect the views of Vedder Price P.C. on any of the matters addressed herein. The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Erin Zavalko-Babej, a former associate at Vedder Price P.C., in the prepara- tion of this article. 157 Uniform Commercial Code Law Journal [Vol. 42 #2] I. INTRODUCTION Issues faced by a secured party in foreclosing on its collat- eral are particularly troublesome in leveraged lease1 or other secured transactions in which the collateral includes intangibles such as the rights of a lessor under a lease of personal property and the right to le a proof of claim against a lessee that may be appropriate if the lessee les a petition for relief under the bankruptcy code, 11 U.S.C.A. -

Conventional Vs. Collateral Mortgage Charges

All our mortgage loans are secured by real property Conventional Charge: such as a house. The Bank of Nova Scotia (carrying (in Quebec, this is referred to as an “immovable on business as "Scotiabank") or Scotia Mortgage hypothec”): Corporation (SMC) will obtain mortgage security that will be registered on title against your home in the The conventional charge is granted in favour of Scotia Conventional vs. appropriate land registry office. This is referred to as Mortgage Corporation (SMC), a wholly-owned the registration of a mortgage or a "charge" and it subsidiary of Scotiabank, and is registered in first Collateral Mortgage gives Scotiabank the legal right to take action against position priority against the home. The conventional you and your home and sell it to get our money back charge covers both the land and building. Charges if you do not pay as promised or honour the terms of The specific details of the mortgage loan such as the your mortgage loan with us. amount, term, payment amount and due date and interest rate are included in the charge registered on title against your home. Collateral Charge: This conventional charge secures only the amount of The collateral charge is granted in favour of the mortgage loan. There may be costs such as legal, Scotiabank and is registered in first position priority administrative and registration costs. against the home usually for an amount that is greater than the actual amount of the mortgage loan. By registering the collateral charge for a higher Comparing Collateral Charge Mortgages -

2021 Q2 Lending and Collateral Q&A

FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK SYSTEM Lending and Collateral Q&A August 13, 2021 Note - Each answer in this document is written as if it were a stand-alone response. Therefore, some information may be repeated. What is an advance and how do advances work? The FHLBanks provide funding to members and housing associates through secured loans known as advances. Each FHLBank makes advances based on the security of mortgage loans and other types of eligible collateral pledged by the borrowing institutions. Advances are the FHLBanks' largest asset category on a combined basis, representing 50.2% and 51.5% of combined total assets at June 30, 2021 and December 31, 2020. Advances are secured by mortgage loans held in borrower portfolios and other eligible collateral pledged by borrowers. Because members may originate loans that are not sold in the secondary mortgage market, FHLBank advances can serve as a funding source for a variety of mortgages, including those focused on very low-, low-, and moderate-income households. In addition, FHLBank advances can provide interim funding for those members that choose to sell or securitize their mortgages. Each FHLBank develops its advance programs to meet the particular needs of its borrowers, consistent with the safe and sound operation of the FHLBank. Each FHLBank offers a wide range of fixed- and variable-rate advance products with different maturities, interest rates, payment characteristics, and optionality, with maturities ranging from one day to 30 years. Who can borrow from the FHLBanks? The FHLBanks are cooperative institutions, and each FHLBank conducts its advance business almost exclusively with its members and housing associates. -

Real Estate Collateral Value and Investment

Journal of Urban Economics 86 (2015) 43–53 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Urban Economics www.elsevier.com/locate/jue Real estate collateral value and investment: The case of China ⇑ Jing Wu a, Joseph Gyourko b,c, Yongheng Deng d,e, a Hang Lung Center for Real Estate, Department of Construction Management, Tsinghua University, China b The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, United States c NBER, United States d Institute of Real Estate Studies, National University of Singapore, Singapore e Department of Real Estate, and Department of Finance, National University of Singapore, Singapore article info abstract Article history: Previous research on the United States and Japan finds economically large impacts of changing real estate Received 28 June 2014 collateral value on firm investment that amplified the business cycles of those countries. Working with Revised 12 December 2014 unique data on land values in 35 major Chinese markets and a panel of firms outside the real estate Available online 25 December 2014 industry, we estimate investment equations that yield no evidence of a collateral channel effect. Further analysis indicates that China’s debt is not characterized by the frictions that give rise to collateral channel JEL classification: effects elsewhere. Essentially, financially constrained borrowers appear able credibly to commit to repay R3 debt in China. While there is no impact on investment via the collateral channel, our results should not be G32 interpreted as implying there will be no negative fallout from a potential real estate bust on the Chinese O5 D22 economy. There likely would be, but through different channels. -

Secondary Mortgage Market - a Catalyst for Change in Real Estate Transactions, The

SMU Law Review Volume 39 Issue 5 Article 3 1985 Secondary Mortgage Market - A Catalyst for Change in Real Estate Transactions, The Robin Paul Malloy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Robin Paul Malloy, Secondary Mortgage Market - A Catalyst for Change in Real Estate Transactions, The, 39 SW L.J. 991 (1985) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol39/iss5/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE SECONDARY MORTGAGE MARKET- A CATALYST FOR CHANGE IN REAL ESTATE TRANSACTIONS by Robin Paul Malloy* HE impact of the secondary mortgage market on real estate transac- tions is likely to be regarded as one of the most important develop- ments in real property and finance law in the 1980s. Underlying the technical jargon and mechanical functions of this market is a process of in- teraction that will bring forth significant economic, social, and political change. The financial incentives propelling the dramatic growth of the sec- ondary mortgage market are already changing the way that lenders, borrow- ers, developers, and investors in real estate interact. Likewise, the growth of the market is causing a reassessment of the proper role of state and federal governments in administering and developing the law of real property. Real property law is shifting from a matter of state and local concern to one of national concern so that the necessary resources of interregional, national, and international capital markets will continue to be available for real estate development. -

The Secured Landlord: Creating a Security Interest in Tenant's Property

Real Estate Law Real Estate nlike in other states, Minnesota landlords do not enjoy a statutory right to levy upon the property of a defaulting tenant. Further, distress (a common law right of a landlord to seize a tenant’s property to satisfy unpaid rent) has been abolished in Minnesota, even if otherwise U 1 agreed upon in the lease. In order to obtain a lien on tenant’s property, a Minnesota landlord needs to create a security interest in the tenant’s property pursuant to the Uniform Commercial Code (“UCC”) set forth in Minnesota Statutes Chapter 336. The following elements are required in order for a valid UCC security interest to be created2: 1. There must be express wording in the lease creating a security interest and describing the collateral3. 2. The description of the collateral should reasonably identify the collateral to ensure that it encompasses all of the tenant’s property, including any collateral acquired by the tenant during the lease term4. 3. The security interest must attach, which occurs when the tenant: (i) signs the security agreement (i.e., the lease); (ii) gives value (i.e., signs the lease); and (iii) has rights in the collateral or the power to transfer rights in the collateral to the landlord5. Th e Secured Even if a tenant signs a lease satisfying the above requirements, the landlord’s security interest will not have priority over security interests previously granted by the tenant unless the landlord properly perfects a purchase money security interest under the UCC. The landlord must perfect its security Landlord: interest by fi ling a fi nancing statement with the proper fi ling offi ce. -

Act of Collateral Mortgage, Pledge

ACT OF COLLATERAL MORTGAGE, PLEDGE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND ASSIGNMENT OF PRODUCTION - THE STATE O? LOUISIANA BY: TAYLOR ENERGY COMPANY PARISH OF OHLEANS TO: ANY FUTURE HOLDER OR HOLDERS BE IT KNOWN, that on this 29th day of January, 1986, before rae, the undersigned Notary Public, duly commissioned, qualified and sworn within and for the State and Parish aforesaid, and therein residing, and in the presence of the undersigned competent witnesses, personally came and apr"' *ed*. TAYLOR ENERGY COMPANY„ a Louisiana corporation, wh addrsss is The 2-3-4 Loyola Building, New Or lea., r, Louisiana 70012 ("Mortgagor") , appearing herein *.nrc . J Patrick P. Taylor, its President, duly authorized pursuant to corporate resolution certified on January 29th, 1986, a certified copy of which is attache i hereto as Schedule I; who declared unto me, Notary, that, desiring to secure func« :"iocn any person, firm or corporation willing to loan same, Mortgagor does by these presents declare and acknowledge a debt in the :-.um Of SEVENTY-FIVE MILLION AND NO/100 DOLLARS <$75 , C00 , 000.00) , anc to evidence such indebtedness, has. executed, under date of these presents, its one (1) certain promissory note ("Said Note"), which is described as follows, to-witt One Collateral Mortgage Note of even dato herewith in the original principal amount of SEVEKTY-FIVE MILLION AND NO/100 DOLLARS ($75,000,000.00), , yable to tho order of BEARER on Demand with interest and attorneys fees as provided therein. All payments on Said Note (an unexecuted copy of which is attached hereto as Schedule II) snd all additional amounts secured herein shall be payable at the banking quarters of First National Bank of Commerce, 210 Baronne Street, New Orleans, Louisiana.