On the Crimes of Rebellion and Sedition. ENRIQUE GIMBERNAT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joint Committee on Public Petitions, Houses of the Oireachtas, Republic

^<1 AM p,I , .S' Ae RECEIVED r , ,1FEB2i2{ a Co GII C' CS, I ^'b' Via t\ SGIrbhis Thith an 01 ea htais @ Houses of the Oireachtas Service TITHE AN O^REACHTAZS . AN COMHCH01STE UM ACHAINtOCHA ON bPOBAL HOUSES OF THE OrREACHTAS JOINT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC PET^TiONS SUBM^SS^ON OF THE SECRETARIAT OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC PETITIONS - IRELAND ^NqUIRY INTO THE FUNCTIONS, PROCESSES AND PROCEDURES . OF THE STANDING COMMITrEE ON ENv^RONMENT AND PUBLrc AFFAIRS LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL WESTERN AUSTRAL^A Houses of the Oireachtas Leinster House Kildare St Dublin 2 Do2 xR2o Ireland ,.,. February 2020 II'~ API ~~ ~, I -,/' -.<,, ,:; -.. t . Contents I . I n trod u ct io n ...,............................................................................................................ 4 2. Joint Committee on Public Service Oversight and Public Petitions 2 0 I I - 2 0 I 6 ..........................................................,.,,.....,.,,.,,,....................................... 5 3. Composition, Purpose, Powers of the Joint Committee on Public Service Oversig ht a rid Pu blic Petitions 201 I- 2016. .................................... 6 3.2 The Joint sub-Committee on Pu blic Petitions 2011 '20/6 ................,..,,,. 7 3.3 The Joint Sub-Committee on the Ombudsman 2011-2016. ................... 9 4. Joint Committee on Public Petitions 2016 - 2020 ...................................,. 10 4.2. Functions of the Joint Committee on Public Petitions 201.6-2020 .... 10 4.3. Powers of the Joint Committee on Public Petitions 201.6-2020 ..... 10 Figu re I : Differences of remit between Joint Committees ........,................,. 12 5 . Ad mis si bi lity of P etitio n s ...................,.., . .................... ....,,,, ... ... ......,.,,,.,.,....... 14 5.2 . In ad missi bin ty of Petitio ns .,,,........,,,,,,,,.., ................... ..,,,........ ., .,. .................. Is 5.3. Consideration of Petitio ns by the Committee. -

Relations with Other State Powers

THE BULLETIN The Venice Commission was requested by the Constitutional Court of Romania, currently holding the presidency of the Conference of European Constitutional Courts (CECC), to produce a working document on the topic chosen by its Circle of Presidents at the preparatory meeting in Bucharest in October 2009 for the XV th Congress of the CECC. The topic was the following: “The relations of the Constitutional Court with other state authorities. Sub-topic 1: relations between the Constitutional Court and parliament. Sub-topic 2: conflicts of competence. Sub-topic 3: the execution of judgments.” The present working document is a contribution by the Venice Commission to the success of the Congress. Constitutional courts are the independent guarantors of the constitution and their main task is to protect the supremacy of the constitution over ordinary law. Over time, however, these courts have taken on further tasks, such as safeguarding the individual against the excess of the executive or providing a safeguard against judicial errors. Another very important role of these courts is to act as a neutral arbiter in cases of conflict between state bodies. Parties to such a conflict know that they can turn to the Constitutional Court for a decision that will help them in resolving their conflict based on the constitution. The possibility of turning to the court in itself sometimes incites them to settle their disputes before they even reach the court. In order to function correctly as an effective institution that stands above the parties in such a dispute, Constitutional Courts need to be independent and need to be seen as being independent. -

UNDP RS NARS and Indepen

The National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia Serbia AND INDEPENDENT BODIES SERBIA THE REPUBLIC OF OF ASSEMBLY NATIONAL NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AND INDEPENDENT BODIES 253 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AND INDEPENDENT BODIES NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AND INDEPENDENT BODIES Materials from the Conference ”National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia and Independent Bodies” Belgrade, 26-27 November 2009 and an Overview of the Examples of International Practice Olivera PURIĆ UNDP Deputy Resident Representative a.i. Edited by Boris ČAMERNIK, Jelena MANIĆ and Biljana LEDENIČAN The following have participated: Velibor POPOVIĆ, Maja ŠTERNIĆ, Jelena MACURA MARINKOVIĆ Translated by: Novica PETROVIĆ Isidora VLASAK English text revised by: Charles ROBERTSON Design and layout Branislav STANKOVIĆ Copy editing Jasmina SELMANOVIĆ Printing Stylos, Novi Sad Number of copies 150 in English language and 350 in Serbian language For the publisher United Nations Development Programme, Country Office Serbia Internacionalnih brigada 69, 11000 Beograd, +381 11 2040400, www.undp.org.rs ISBN – 978-86-7728-125-0 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations and the United Nations Development Programme. Acknowledgement We would like to thank all those whose hard work has made this publication possible. We are particularly grateful for the guidance and support of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia, above all from the Cabinet of the Speaker and the Secretariat. A special debt of gratitude is owed to the representatives of the independent regulatory bodies; the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Personal Data Protection, the State Audit Institution, the Ombudsman of the Republic of Serbia and the Anti-corruption Agency. -

How Has European Integration Impacted Regionalist Political Parties’ Electoral Support?

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2021 A Europe of Regionalists: How Has European Integration Impacted Regionalist Political Parties’ Electoral Support? Brandon N. Piel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Piel, Brandon N., "A Europe of Regionalists: How Has European Integration Impacted Regionalist Political Parties’ Electoral Support?" (2021). CMC Senior Theses. 2669. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2669 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College A Europe of Regionalists: How has European integration impacted regionalist political parties’ electoral support? Submitted to Professor Lisa Langdon Koch by Brandon N. Piel for Senior Thesis Fall 2020 – Spring 2021 April 26, 2021 Abstract This study investigates the question: How has European integration impacted regionalist political parties’ electoral support? European integration and regionalism are theoretically connected by Seth Jolly’s viability theory which explains that supranational organizations, such as the European Union (and precursor organizations), make small countries more viable. Using the regions of Flanders, Corsica, Sardinia, Padania, Galicia, and Catalonia as case studies, this thesis identifies -

The Irish Language and the Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present

The Irish Language and The Irish Legal System:- 1922 to Present By Seán Ó Conaill, BCL, LLM Submitted for the Award of PhD at the School of Welsh at Cardiff University, 2013 Head of School: Professor Sioned Davies Supervisor: Professor Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost Professor Colin Williams 1 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… 2 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… -

Kierkegaard Història Memòria

CATALAN SOCIAL SCIENCES REVIEW, 7: 77-86 (2017) Secció de Filosofia i Ciències Socials, IEC, Barcelona ISSN: 2014-6035 DOI: 10.2436/20.3000.02.37 http://revistes.iec.cat/index/CSSr The Parliament of Catalonia, representing a millenary people Marcel Mateu Vilaseca* Universitat Oberta de Catalunya Original source: Revista de Dret Històric Català, 13: 177-187 (2014) (http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/RDHC/index) Translated from Catalan by Mary Black Abstract Catalonia is a millenary nation, which the current Spanish constitutional order frames as an “autonomous community”. However, Catalonia as a nation was not born with the Spanish Constitution in 1978, nor has any possibility for the future been democratically barred. The most important contribution to Catalonia made by the 1978 Constitution was to make it possible for the Catalan Statute to create the Catalan Parliament, an institution that democratically represents the people of Catalonia and legally structures and channels the people’s voice. The Parliament’s agreement at the end of the Ninth Legislature, which declares the need for the people of Catalonia to exercise the right of self-determination, opens up a new stage in the history of Catalonia. Key words: Parliament, representative function, Catalonia, Constitution, people, self-determination, democracy. Catalonia is a millenary nation, which the current Spanish constitutional order frames as an “autonomous community”. However, Catalonia as a nation was not born with the Spanish Constitution (SC) in 1978, nor has any possibility for the future been democratically barred. It seems obvious, but I believe it needs to be said, because some voices seem to have forgotten this, while others stubbornly deny it time and time again. -

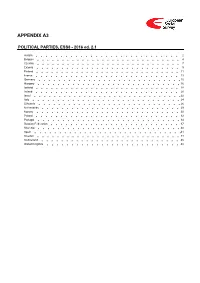

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Brussels, 20 June 2019 To: the President of The

Brussels, 20 June 2019 To: The President of the European Parliament Cc: The Chairman of the Committee on Legal Affairs From: Carles Puigdemont i Casamajó, and Antoni Comín i Oliveres, elected Members of the European Parliament - Having regard to our previous letter of 14 June 2019; - Having regard to the results of the elections to the European Parliament of 26 May 2019 officially declared by Spain in accordance with Articles 8 and 12 of the Electoral Act 1976, which were published in the Spanish Official Gazette of 14 June 2019, and confirm that we have been officially declared as elected Members of the European Parliament (see documents attached), - Having regard to the decision of the investigative judge of the Spanish Supreme Court of 14 June 2019 not to withdraw the existing national arrest warrants against us, following our election as new Members of the European Parliament, so that we could be sworn in and take our seats normally (see document attached), - Having regard to the decisions by the investigative judge of the Spanish Supreme Court to withdraw the European Arrest Warrants issued against us in November 2017 and March 2018, and particularly to the decision of the Court of Schleswig-Holstein which declared that the extradition on charges of rebellion or sedition was inadmissible (see document attached), - Having regard to the fact that the charges of rebellion, sedition and misuse of public funds brought by the investigative judge of the Spanish Supreme Court against us are the exact same charges, on the exact same facts, brought against Mr. Jordi Cuixart, against Mr. -

Post-Conflict Constitution Drafter's Handbook

A Global Pro Bono Law Firm Post-Conflict Constitution Drafter’s Handbook Prepared by The Public International Law & Policy Group Paul R. Williams, Executive Director Elizabeth Hahn, Post-Conflict Constitution Project Director Cassandra Tillinghast, Senior Research Associate Emily Nugent, Senior Research Associate January 2007 Post-Conflict Constitution Drafter’s Handbook January 2007 NOTE FOR USERS The Public International Law & Policy Group’s (PILPG) Post-Conflict Constitution Drafter’s Handbook is a guide intended to effectively assist drafters of constitutions in post-conflict situations. The Handbook draws from PILPG’s experience in facilitating post-conflict constitutional drafting as well as common state practice, and is based upon comparative analysis of over 150 constitutions from post-conflict states and from long stable countries. The Handbook divides the core provisions commonly found in post-conflict constitutions into individual chapters. The chapters include: Preamble Provisions, State Structure and Devolution of Powers, the Executive, the Legislature, the Judiciary, Electoral System, Financial Matters and the Central Bank, Human Rights, Minority Rights, Women's Rights, Defense and Security, the Role of Religion, Natural Resources, and Extraordinary Measures. In each chapter, the Handbook describes core provisions and provides sample language options for drafters to incorporate into their constitutions. In some cases, the drafter may select sample language from a variety of options. In these instances, the sample language is identified as “Option One” and “Option Two.” In other cases, the Handbook provides optional language that drafters may or may not wish to include. In those instances the sample language is identified as “Optional.” Because every post-conflict situation is unique, the drafter may have to make adjustments to certain elements to enhance the constitution’s relevance and applicability to a particular context. -

Regional Autonomy in the European Union

REGIONAL AUTONOMY IN THE EUROPEAN UNION by William John Hopkins PhD Thesis University of Sheffield Faculty of Law Volume Two of Two November, 1996 VOLUME TWO PART THREE 359 8 - Regional Autonomy in the European Union 359 8.1 Ordinal Comparison 360 8.2 Collective Influence or Regional Autonomy? 374 8.3 The Rise of Executives 378 8.4 RecentraIisation and Local Autonomy 381 8.5 A Regional Alternative to the Nation-State? 392 8.6 A Europe of Regions? 398 9 - Regional Government and the U.K. 401 9.1 European Lessons 404 9.1(a) Structure 406 9.I(b) Finance 412 9 .1 (c) Functions 414 9.I(d) Local Government 416 9.I(e) The "West Lothian" Question 417 9.2 Scotland 421 9.3 England 430 9.4 Wales 434 9.5 A Blueprint for Britain? 436 APPENDICES 440 I - Regional Structures In The European Union 440 1.1 Belgium 440 1.1 (a) Development 440 1.1 (b) Structure 442 1.1 (c) Constitutional Position 447 1.l(d) Brussels 449 1.2 Denmark 450 1.2(a) Development 451 1.2(b) Structure 452 1.2( c) Constitutional Provisions 453 1.3 France 454 1.3(a) Development 454 1.3(b) Structure 456 I.3(c) Constitutional Position 459 l.3(d) Corsica 462 l.3(d)i Development of Corsican "Special Status" 462 l.3(d)ii Corsican Regional Structures 463 1.3(d)iii Constitutional Provisions 464 1.4 Germany 464 1.4(a) Development 464 1.4(b) Structure 465 1.4(c) Constitutional Position 469 1.5 Greece 472 1.5(a) Development 472 1.5(b) Structure 472 1.5(c) Constitutional Provisions 473 1.6 Ireland 474 1.7 Italy 474 1.7(a) Development 474 1.7(b) Structure 475 I.7(c) Constitutional Provisions 477 -

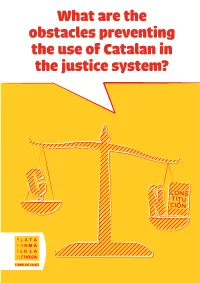

What Are the Obstacles Preventing the Use of Catalan in the Justice System?

What are the obstacles preventing the use of Catalan in the justice system? CONS TITU CIÓN Introduction 03 1. The language skills of justice administration staff 04 2. The language of judicial proceedings 08 3. Citizens’ rights when dealing with 14 the Administration of Justice 4. Working material in Spanish 17 5. The language of justice in the central and higher institutions 20 6. The Spanish Constitutional Court 22 7. Training jurists: from university to the Judicial School 24 8. Legal agreements and relationships in an international context 26 9. Habits and inertia 28 10. Fear of speaking one’s own language, 29 even when there is a legal right to do so Conclusions 31 Plataforma per la Llengua / March 2020 Introduction This document is the second edition of a report published in March 2017. We have updated the content, expanded some points and added new figures. The Administration of Justice continues to be one of the areas where the use of Catalan is precarious, and, in fact, almost entirely absent. In this report, we analyse why, despite several initiatives, various programmes, many strategies and a great deal of resources devoted to overturning this situation, we still find ourselves in a position we can describe as a “language desert” for Catalan in this sector. What are the main reasons why Catalan is in such a critical and almost invisible position today? Barcelona, January 2020 © Plataforma per la Llengua 3 What are the obstacles preventing the use Plataforma per la Llengua / March 2020 of Catalan in the justice system? Royal Decree 1451/2005 on the provision of civil service posts in the Administration of 1. -

Free Fulltext

The European Journal of International Law Vol. 30 no. 4 © The Author(s), 2020. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of EJIL Ltd. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: [email protected] Editorial Editorial: Celebrating Peer Review: EJIL’s Roll of Honour and Announcement of the first EJIL Peer Review Prize; Brexit – Apportioning the Blame; Once Upon a Time in Catalonia…; 10 Good Reads; In This Issue Celebrating Peer Review: EJIL’s Roll of Honour and Announcement of the first EJIL Peer Review Prize What makes for a good scholar? Brilliant articles and inspiring lectures – important, but not enough. No matter how solitary scholarly work can feel, it is always embedded in and dependent on a community: a community in which ideas are shared, reviewed and discussed. I hope that many of us will be able to think of some scholars who were stellar because they fundamentally shaped our thinking and writing by investing time, ideas and experience beyond the call of duty – detailed comments on a draft; meet- ings to discuss ways forward; endless letters of reference. You know who they are, and hopefully there are opportunities to say thanks to these academic parents, and pay it forward. Saying thanks is more difficult, however, with peer reviewers: they, too, can funda- mentally improve the quality of a piece of work, and yet it is inherent in the exercise that the author does not know – indeed should not know – who they were. Vice-versa, for peer reviewers, the work can feel like a thankless task. They spend considerable time analysing an article, engaging with the ideas and writing up constructive sug- gestions, without the author ever knowing who put that effort into their work.