Access to and Utilization of Academic Information by Students and Staff at Kabarak University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

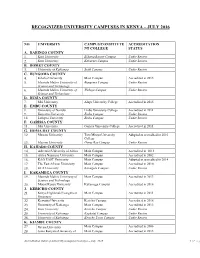

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

DANIEL OTIENO Qualification: Phd Department: Education

Academic Staff Profile 1.1 Personal Profile 1.1.1 Personal Details Name: DANIEL OTIENO Qualification: PhD Department: Educational Management, Policy and Curriculum Studies Designation/Position: Lecturer Email: [email protected] Contact Address: 43844-00200 Nairobi Area of Specialization: Educational Administration, Research Methods, Values- based Education, Leadership and Coaching Research Interests: Values Education, Organisational Development, Change management, Internationalisation, ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002- 3212-9058 Researcher ID: F-2940-2019 1.1.2 Academic & Professional Qualifications - PhD (Educational Administration) - M.Ed (Educational Administration) - B.Ed (Arts) 1.1.3 Employment History -10th September 2018 – Present: Lecturer, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya - 4th August 2017 – 10th September 2018: Tutorial Fellow, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya - 6th December 2011 – 3rd August 2017: Lecturer, Africa Nazarene University - 20th Sept 2010 – 6th December 2011: Part-time Lecturer, Africa Nazarene University, Kenya - January 1999 – 30th January 2009: Principal, Sathya Sai School - 1.1.4 Special Appointments - 1st February 2019 Appointed by the Dean to the School of Education International Annual Conference on Education and Lifelong Learning committee. Member of the planning committees for renewable five-year term. - 6th February 2019 to date Appointed to as External Examiner in the Department of Education – Africa Nazarene University. Examining Master of Education thesis. - 7th February 2019 Appointed to the Conference planning committee on career mentoring and leadership. - 20th August 2018 Appointed by Chair of Department as member of conference editorial committee of the 3rd International conference on Education Planning Committee. Kenyatta University - 13th March 2018 Appointed by the Dean to the ISO Quality Team to Evaluate the implementation of Departmental Key Performance Indicators (KRI) - 1.2 Publications 1.2.1 Referred Journals Otieno, D. -

N O Institution's Name Public University 1 Chuka University 2 Dedan Kimathi University of Technology 3 Egerton University 4 Ja

N Institution’s Name o Public University 1 Chuka University 2 Dedan Kimathi University of Technology 3 Egerton University 4 Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology 5 Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture & Technology (JKUAT) 6 Karatina University 7 Kenyatta University 8 Kisii University 9 Laikipia University 10 Masai Mara University 11 Maseno University 12 Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology 13 Meru University of Science and Technology 14 Moi University 15 Multi Media University 16 Pwani University 17 South Eastern Kenya University 18 Technical Univeristy of Mombasa 19 Technical University of Kenya 20 University of Eldoret 21 University of Kabianga 22 University of Nairobi Private University 23 Adventist University of Africa 24 Africa International University 25 Africa Nazarene University 26 Aga Khan University 27 Catholic University Of Eastern Africa 28 Daystar University 29 East African University 30 Great Lakes University 31 International University of Professional Studies 32 International Leadership University 33 Kabarak University 34 KCA University 35 Kenya Methodist University 36 Mount Kenya University 37 Pan Africa Christian University 38 Pioneer International University 39 Scott Christian University 40 St Paul's University 41 Strathmore University 42 The Management University of Africa 43 The Presbyterian University of East Africa 44 Umma University 45 United States International University 46 University of Eastern Africa, Baraton University College 47 Co-operative University College 48 Embu -

Download 3623.Pdf

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 5, Issue, 07, pp.2002-2009, July, 2013 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE AN ASSESSMENT OF STRATEGIC FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE STUDENT CHOICE: A CASE OF KABARAK UNIVERSITY *Kimno William Kipkemoi Department of Business Administration, Egerton University, Kenya ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: This study assessed the influence of strategic factors on students’ choice of Kabarak University. The study Received 24th April, 2013 considered the following specific objectives; to determine the enrolment trends at Kabarak University, to Received in revised form determine the extent to which financial factors influence the students’ choice of Kabarak University, to determine 16th May, 2013 the extent to which marketing factors influence the students’ choice of Kabarak University. It adopted Census Accepted 15th June, 2013 method to select the six (6) members of management, while systematic random sampling technique was used to Published online 17th July, 2013 select two hundred and eighty (280) students to whom questionnaires were administered. Descriptive statistics and factor analysis was used to analyse the data. The questionnare was the main instrument used for data collection. Key words: The study found out those financial factors such as, flexible fees payment policy influenced students’ choice to the Strategic factors, university more than more than the martketing factors such as product development. The paper recommends that Enrolment trends and to improve enrolment in the University, there is need to recognize the fact that Kabarak university enrolment is declining and thus the University should design, implement and evaluate all inclusive change strategies. -

Book of Abstracts

Kabarak University International Conference on Emerging Trends and Issues in Education Tuesday 23 October 2018 - Tuesday 23 October 2018 KLAW - Conference Center Book of Abstracts Contents Impact of Family Structure and Family Change in Child Outcome: A case Study of Under- graduate Students of Kabarak University ......................... 1 Can Church Conflict Inhibit Moral Development and Christian Formation? A Study of Emmanuel Kengeleni Parish of Mombasa Diocese in the Anglican Church of Kenya (2000-2010). ......................................... 1 PREVALENCE,PERCEPTION AND CONSEQUENCES OF SEXUAL HARASSMENT IN KENYAN INSTITUTIONS OF HIGHER LEARNING ......................... 2 Social Media Neologisms; Made in Kenya for Kenyans: A case Study of Facebook . 2 Can’t pay won’t pay; Struggle of Kenyan Teachers in their Quest for Better Terms and Remuneration ........................................ 3 STUDENTS’ PERCEPTION OF THE TEACHING PROFESSION AS AN ANTECEDENTS OF SUSTAINABILITY IN TEACHER EDUCATION ..................... 3 IMPACT OF THE FAMILY STRUCTURE ON ACADEMIC PROGRESSION AND BEHAVIOUR OF HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN RONGAI CONSTITUENCY IN NAKURU COUNTY. ........................ 4 TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES THAT HAS ENABLED MAN TO ADAPT TO THE PHYS- ICAL ENVIRONMENT; A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE. ................ 4 GENDER INEQUALITY IN ENROLMENT FOR ACCOUNTANCY PROGRAMME IN NIGE- RIA FEDERAL POLYTECHNICS: EMERGING ISSUES IN EDUCATION . 5 MULTIMODAL ANALYSIS OF POLITICAL CAMPAIGN POSTERS IN THE 2017 GENERAL ELECTIONS -

Availability and Use of Media Resources in Teaching and Learning: a Case of Selected Secondary Schools for the Hearing Impaired in Western Kenya

AVAILABILITY AND USE OF MEDIA RESOURCES IN TEACHING AND LEARNING: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS FOR THE HEARING IMPAIRED IN WESTERN KENYA By Ondicho Rosemary M. Nyaundi A Thesis presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research, Kabarak University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Curriculum and Instruction November, 2015 DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. No part of this thesis may be reproduced without the prior permission of the author and/or Kabarak University. Student Signature _____________________ Date_______________ Student Name_________________________ Admission Number ____________________ Kabarak University ii RECOMMENDATION To The Institute of Postgraduate Studies The Thesis entitled “Availability and use of media resources in teaching and learning of the hearing impaired students” and written by Ondicho Rosemary M. Nyaundi is presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies and Research of Kabarak University. We have reviewed the thesis and recommend it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Curriculum and Instruction _____________________________ Date________________________ Dr. Kageni Njagi Senior Lecturer Department of Education Kabarak University ___________________________ Date_________________________ Prof T.M. Ayodo Dean Faculty of Education and Theology Kabarak University November, 2015 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to register my sincere appreciation to all those who, in different ways have contributed to the success of this thesis. First and foremost, I am indebted to the level of tolerance and inputs accorded by my supervisors Dr. Njagi Kagen and Prof. T. M Ayodo of the Faculty of Education and Theology. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : James Kamau Gatoto INSTITUTION ADDRESS Kenyatta University, Department of Mathematics P.O. Box43844-00100, Nairobi KENYA 1. EDUCATION 1993-1996 Ph.D in Mathematics. Egerton University -Kenya Thesis title: A CONTRIBUTION TO FINSLER AND CONFORMAL FINSLER SPACES. (Funding awarded by Egerton University) Supervisor: Prof. S.P. Singh (A leading Scholar in Differential Geometry of Generalized Spaces) 1980-1985 M Sc. in Mathematics, University of Kharkov (Ukraine) Thesis title: Properties of Grassman Image of Minimal Surface in the Four-dimension Euclidean Space. Supervisor: Prof. Yuriy A. Aminov (A leading Researcher and Scholar in Differential Geometry of Sub-manifolds) 1979-1980 Russian Language Course, University of Kharkov (Ukraine) 1977-1978 EAACE -2 Principals (Aga Khan High School, Nairobi) 1973-1976 EACE -1st Division (Aga Khan High School, Nairobi) 1966-1972 CPE (Martin Luther Primary School, Nairobi) 2. TEACHING AND OTHER RELATED EXPERIENCES (a) Kenyatta University January 2011: Associate Professor, Department of Mathematics (b) Egerton University March 2008: Associate Professor, Department of Mathematics June1999-to Feb 2008: Senior Lecturer, Dept .of Mathematics. Dec 1992- June 1999: Lecturer, Department of Mathematics June 1991-Nov 1992: Assistant Lecturer, Department of Mathematics (c) Kabarak University Sept 2004-Dec 2004: Part- Time Lecturer (Vector Geometry) (d) Warazo Jet Secondary School, Nyeri Jan 1991-June 1991: Headmaster (e) Kagumo High School, Nyeri Sept 1985- Jan 1991: Mathematics Teacher. Sept 1986-Oct 1987: Teacher in charge of Counselling and Careers Guidance. Oct. 1987-Jan1991: Deputy Headmaster. 3. PROFESSIONAL TRAINING 1 (a) Egerton University 1992-1996: Research in Differential Geometry (b) University of Kharkov 1980-1985: Trained in Mathematics, Pedagogy and Psychology 4. -

Kabarak University Courses Pdf

Kabarak university courses pdf Continue Kabarak University courses online applying various accredited universities offer courses in education for potential students who want to be teachers. Universities have course specific requirements for various art and science courses. They also offer different combinations of training subjects. Here are the educational courses offered at Kabarak University and links to their application portals: KABARAK EDUCATION COURSES wpedon id734 leveling center University offers a wide range of training courses in its Faculty of Education. Minimum entry to the University of The Bachelor's Degree program requires a minimum middle class C (C Plus) in KCSE. OR a minimum credit pass at the diploma level or equivalent qualification from recognized institutions. OR 2 Basic 'A' passes received for one sitting or two basic passes received at different meetings, provided that the points have a class of C and above. Applicants must also meet additional entry requirements, as can be stated by the relevant departments. Applications from mature students will be considered on the condition that they meet the conditions of admission to the university. Holders of diplomas in pedagogical education with a minimum of HG in KCSE and two years of teaching experience. P1 teacher certificate holders with minimal experience at KCSE and two years of teaching experience. BACHELOR OF EDUCATION (SCIENCE) COURSES/ SUBJECTS COMBINATIONS University offers a Bachelor of Education (Science) course in the following academic subjects: mathematics, physics, biology, agriculture, chemistry and computer research. The student can choose a combination of two items from the listed here. BACHELOR OF EDUCATION (ARTS) COURSES/ SUBJECTS COMBINATIONS University also offers a Bachelor of Education (Arts) course in english, literature, history, music, geography and kiswahi. -

Langat Lydia Chepkoech

UOK/F/DR/1/VOL 1 UNIVERSITY OF KABIANGA ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED ACADEMIC STAFF MEMBER’S PROFILE Langat Lydia Chepkoech PERSONAL DETAILS Photo ADDESS: 2030 – 20200 Kericho CURRENT ACADEMIC RANK ( eg Lecturer)… Tutorial Fellow GENDER: Female CURRENT RESPONSIBILITY (HoD, Dean, Director, etc)…… Lecturer/Unit Head: None EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] Telephone No. Office: None Mobile: 0726989877 Personal website: None EDUCATION QUALIFICATION 2014-2017: Doctor of Philosophy Business Administration (Marketing Option) Kabarak University. 2013- 2016: Masters in Business Administration (MBA, Marketing Management), Kabarak University. 2008-2012: Masters in Business Administration (MBA, Strategic Management), Egerton University. 2004-2007: Bachelor of Business Management (Marketing Option), 1 Moi University. 2002-2004: Kenya Institute of Management (Nakuru Branch)- Diploma 1&2, Advanced Certificate and certificate. 1996-1999: Kenya Certificate of secondary education (KCSE) Kirobon High School. 1987-1994: Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE). Kilimo Primary School. FIELD OR AREA OF SPECIALIZATION Marketing PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATION Full Member of Marketing Society of Kenya-Member No-M1062/MSK TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2015 To date: University of Kabianga (Tutorial Fellow) 2013 - 2015: Laikipia University, Nyahururu Campus (Part Time Lecturer) 2013 -2017: St Paul’s University, Nakuru Campus (Part Time Lecturer) 2013 -2015: Presbyterian University of East Africa, Nakuru Campus (Part Time Lecturer) 2012-2013: Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Nakuru Campus (Part Time Lecturer) 2010- 2015: - Mount Kenya University, Nakuru Branch (Part Time Lecturer) 2012 -2015:Riftvalley Institute of Science and Technology (Part Time Lecturer) 2 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS International Publications 1. Langat, L.C., Otuya, R., Chepkilot, R. (2017). Effect of External Branding Strategies on Students’ Choice of Post Graduate Programmes in Universities in Nakuru County, Kenya. -

Examination Centres

NOVEMBER 2020 PREVIOUS AND REVISED EXAMINATION CENTRES Note: Where a candidate’s previously allocated centre is not in the revised list, Kasneb will strive to reallocate the candidate to the next nearest centre, subject to capacity. The shaded centres will not be available for November 2020. To know your previously allocated centre, send the word “Centre” with your registration number to 20558, for example Centre/NAC/your reg.no. In case you wish, due to unavoidable circumstances, to change your centre, send a request through an email to [email protected] with your reg no. and reasons, by Monday, 12 October 2020. Any such change will be subject to availability of capacity and will be communicated to students. Where you have not been allocated a centre and you paid, contact Kasneb immediately through email address [email protected] attaching relevant evidence. CENTRE CENTRE No. COUNTY PREVIOUS EXAMINATION CENTRES CODE COUNTY CURRENT EXAMINATION CENTRES CODE 1. BARINGO K. S. G - BARINGO 350 BARINGO K. S. G - BARINGO 350 BARTEK INSTITUTE – ELDAMA RAVINE 353 BARTEK INSTITUTE – ELDAMA RAVINE 353 2. BOMET BOMET COLLEGE OF ACCOUNTANCY 392 BOMET BOMET UNIVERSITY COLLEGE (PROPOSED) 525 SANG’ALO INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE AND 3. BUNGOMA TECHNOLOGY 338 BUNGOMA KIBABII UNIVERSITY 512 DOMINION TRAINING INSTITUTE - BUNGOMA 365 KIBABII UNIVERSITY 512 4. BUSIA YMCA BUSIA 349 BUSIA BUSIA DICECE (PROPOSED) 526 KCA UNIVERSITY - AMAGORO 509 EMBU JEREMIAH NYAGA TECHNICAL TRAINING 425 EMBU JEREMIAH NYAGA TECHNICAL TRAINING 425 INSTITUTE INSTITUTE 5. EMBU COLLEGE 439 EMBU COLLEGE 439 ACHIEVERS COLLEGE - EMBU 471 NORTH EASTERN NATIONAL NORTH EASTERN NATIONAL POLYTECHNIC - 6. -

Science in Kenya

SCIENCE IN KENYA Scientific institutions in Kenya include the UNESCO Regional Office for Science and Technology for Africa, in Nairobi; coffee and tea research foundations; grasslands and plant-breeding research stations; and numerous centers for medical, agricultural, and veterinary research. Medical research focuses on the study of leprosy and tuberculosis. The National Council for Science and Technology advises the government on scientific matters, and the Kenya National Academy of Sciences promotes advancement of learning and research; both organizations were founded in Nairobi in 1977. The University of Nairobi, founded in 1956, has colleges of agriculture and veterinary sciences, health sciences, architecture and engineering, and biological and physical sciences. Kenyatta University, founded in 1939 at Nairobi, has faculties of science and environmental education. Moi University, founded in 1984 in Eldoret, has faculties of forest resources and wildlife administration, science, technology, information sciences, environmental studies, health sciences, and agriculture. Edgerton University, founded in 1939 at Njoro, has faculties of agriculture and science. Other higher-education institutions include Jomo Kenyatta University College of Agriculture and Technology, Kenya Medical Training College, and Kenya Polytechnic, all in Nairobi, and five other institutes of science and technology elsewhere in the country. In 1987–97, science and engineering students accounted for 19% of college and university enrollments. scientific institutions -

Effect of Branding Strategies on Post Graduate Students’ Choice of Universities in Nakuru County, Kenya

EFFECT OF BRANDING STRATEGIES ON POST GRADUATE STUDENTS’ CHOICE OF UNIVERSITIES IN NAKURU COUNTY, KENYA LYDIA CHEPKOECH LANGAT A Thesis Report presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies of Kabarak University in Partial Fulfillment of the requirement for the Award of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration (Marketing Option). KABARAK UNIVERSITY NOVEMBER, 2017 DECLARATION The report thesis is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it has not been presented for the award of a degree in any university or college. Signed:____________________________________Date:_____________________ Lydia Chepkoech Langat GDB/M/1144/09/14 RECOMMENDATION To the Institute of Postgraduate Studies: The research thesis entitled “Effect of Branding Strategies on Post Graduate Students’ Choice of Universities in Nakuru County, Kenya” and written by Lydia Chepkoech Langat is presented to the Institute of Postgraduate Studies of Kabarak University. We have reviewed the research thesis and recommend it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for award of the degree of of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration Marketing Option. Signed:___________________________________Date:____________________ Dr. Robert Otuya School of Business and Management Science, University of Eldoret Signed:__________________________________Date:____________________ Prof. Ronald Chepkilot School of Business and Economics, Kabarak University COPYRIGHT © 2017 Lydia Chepkoech Langat All rights reserved. No part of this Thesis may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means of photocopy, electronic, mechanical, and recording or any information storage or retrieval system without written permission from the author or Kabarak University. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to humbly acknowledge their encouragement support and inspiration of a number of people in this journey.