Proceedings Book 2.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans-Peter Feldmann Named Winner

Guggenheim and AMO / Rem Koolhaas Announce Research Project Culminating in February 2020 Exhibition Countryside: Future of the World to Examine Radical Changes Transforming the Nonurban Landscape (NEW YORK, NY—November 29, 2017)—The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, architect and urbanist Rem Koolhaas, and AMO, the think tank of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), will collaborate on a project exploring radical changes in the countryside, the vast nonurban areas of Earth. The project extends work underway by AMO / Koolhaas and students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and will culminate in a rotunda exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in February 2020. Organized by Guggenheim Curator of Architecture and Digital Initiatives Troy Conrad Therrien, Founding Partner of OMA Rem Koolhaas, and AMO Director Samir Bantal, Countryside: Future of the World (working title) will present speculations about tomorrow through insights into the countryside of today. The exhibition will explore artificial intelligence and automation, the effects of genetic experimentation, political radicalization, mass and micro migration, large-scale territorial management, human-animal ecosystems, subsidies and tax incentives, the impact of the digital on the physical world, and other developments that are altering landscapes across the globe. “The Guggenheim has an appetite for experimentation and a founding belief in the transformative potential of art and architecture,” said Richard Armstrong, Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation. -

Rem Koolhaas: an Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Volume 16 - 2008 Lehigh Review 2008 Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16 Recommended Citation Fox, Daniel, "Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation" (2008). Volume 16 - 2008. Paper 8. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lehigh Review at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 16 - 2008 by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation by Daniel Fox 22 he three Master Builders (as author Peter Blake refers to them) – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright – each Drown Hall (1908) had a considerable impact on the architec- In 1918, a severe outbreak ture of the twentieth century. These men of Spanish Influenza caused T Drown Hall to be taken over demonstrated innovation, adherence distinct effect on the human condi- by the army (they had been to principle, and a great respect for tion. It is Koolhaas’ focus on layering using Lehigh’s labs for architecture in their own distinc- programmatic elements that leads research during WWI) and tive ways. Although many other an environment of interaction (with turned into a hospital for Le- architects did indeed make a splash other individuals, the architecture, high students after St. Luke’s during the past one hundred years, and the exterior environment) which became overcrowded. Four the Master Builders not only had a transcends the eclectic creations students died while battling great impact on the architecture of of a man who seems to have been the century but also on the archi- influenced by each of the Master the flu in Drown. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Architecture, Form, Expression. the Helicoidal Skyscrapers'geometry

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Architecture, Form, Expression. The Helicoidal Skyscrapers’Geometry Alessandra CAPANNA Dipartimento di Architettura e Progetto “Sapienza” Università di Roma Via Flaminia 359 - 00196 Roma, ITALY E-mail: [email protected] Mauro FRANCAVIGLIA Marcella G. LORENZI Dipartimento di Matematica, Laboratorio per la Comunicazione Scientifica Università di Torino Università della Calabria Via Carlo Alberto,10 - 10123 Torino, ITALY Cubo 30b, 87036 Arcavacata di Rende CS, E-mail: [email protected] ITALY E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Expressionist utopia of an Architect imitating the rigorous and -at the same time- extremely bizarre formative principles of Nature, linked with the engineering “must” of a coherent and correct structure are apparent antithesis if only played as the manifestation of an irrational and uncontrolled freedom. We explore the ancient idea of Harmony and Beauty and the historical confidence in the logarithmic spiral as the symbol of perfection in an un- built project for a 565 m (1,854 ft) high skyscraper that was supposed to be built on the tip of Manhattan, NYC. The role of geometry is no more exploited as an instrument for controlling architectural form, but for its liberation: the project for a helicoidal skyscraper consisted of a succession of warped wings developed on the layout of the logarithmic spiral. The helicoidal shape, works better than the others in splitting up the force of the wind in resistance, has a positive influence on the stability of the building and is the result of a strong design theory wondering about the power of invention, the power of geometry, the power of relationships among numbers, and finally the beauty of (deriving from) mathematics (in Architecture). -

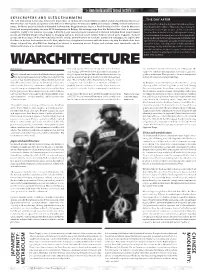

WARCHITECTURE Hinted at the Day Before

IIAS_NL#39 09-12-2005 17:03 Pagina 20 > Rem Koolhaas IIAS annual lecture SKYSCRAPERS AND SLEDGEHAMMERS The 10th IIAS annual lecture was delivered in Amsterdam on 17 November by world-famous Dutch architect and Harvard professor ...THE DAY AFTER Rem Koolhaas. Co-founder and partner of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and initiator of AMO, its think-tank/mirror Zheng Shiling from Shanghai, Xing Ruan from Sydney and Anne- image, Koolhaas’ projects include de Kunsthal in Rotterdam, Guggenheim Las Vegas, a Prada boutique in Soho, Casa da Musica in Marie Broudehoux from Quebec City were Koolhaas’ discussants Porto and most spectacularly, the new CCTV headquarters in Beijing. His writings range from his Delirious New York, a retroactive following the lecture. To give our guests a chance to meet their manifesto (1978) to his massive 1,500 page S,M,L,XL (1995), several projects supervised at Harvard including Great Leap Forward Dutch and Flemish brothers in arms, IIAS organized a meeting (2002) and Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (2002) to his most recent volume between a book and a magazine, Content at the Netherlands Architectural Institute in Rotterdam the fol- (2005). On these pages of the IIAS newsletter, itself a strange animal between an academic journal and newspaper, we explore why lowing day. Bearing the title (Per)forming Culture; Architecture and Koolhaas in his last book invites us to Go East; why he has a long-time fascination with the Asian city; why the Metabolists have Life in the Chinese Megalopolis, specialists of contemporary Chi- always intrigued him; why OMA has developed an interest in preserving ancient Beijing; and, perhaps most importantly, why he nese urban change – including scholars of architectural theory, thinks architecture is so closely connected to ideology. -

Lewis Mumford – Sidewalk Critic

SIDEWALK CRITIC SIDEWALK CRITIC LEWIS MUMFORD’S WRITINGS ON NEW YORK EDITED BY Robert Wojtowicz PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS • NEW YORK Published by Library of Congress Princeton Architectural Press Cataloging-in-Publication Data 37 East 7th Street Mumford, Lewis, 1895‒1990 New York, New York 10003 Sidewalk critic : Lewis Mumford’s 212.995.9620 writings on New York / Robert Wojtowicz, editor. For a free catalog of books, p. cm. call 1.800.722.6657. A selection of essays from the New Visit our web site at www.papress.com. Yorker, published between 1931 and 1940. ©1998 Princeton Architectural Press Includes bibliographical references All rights reserved and index. Printed and bound in the United States ISBN 1-56898-133-3 (alk. paper) 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 First edition 1. Architecture—New York (State) —New York. 2. Architecture, Modern “The Sky Line” is a trademark of the —20th century—New York (State)— New Yorker. New York. 3. New York (N.Y.)— Buildings, structures, etc. I. Wojtowicz, No part of this book my be used or repro- Robert. II. Title. duced in any manner without written NA735.N5M79 1998 permission from the publisher, except in 720’.9747’1—dc21 98-18843 the context of reviews. CIP Editing and design: Endsheets: Midtown Manhattan, Clare Jacobson 1937‒38. Photo by Alexander Alland. Copy editing and indexing: Frontispiece: Portrait of Lewis Mumford Andrew Rubenfeld by George Platt Lynes. Courtesy Estate of George Platt Lynes. Special thanks to: Eugenia Bell, Jane Photograph of the Museum of Modern Garvie, Caroline Green, Dieter Janssen, Art courtesy of the Museum of Modern Therese Kelly, Mark Lamster, Anne Art, New York. -

The Past and Present of Soviet Constructivism The

BOLSHEVISM IN BRICK AND CONCRETE: THE PAST AND PRESENT OF SOVIET CONSTRUCTIVISM DOI 10.15826/qr.2016.3.173 УДК 72/036(063)+72/038/11+72.035.93+725.1(470-25) THE 4TH CIAM CONGRESS IN MOSCOW. PREPARATION AND FAILURE (1928–1933)* ** 2 Thomas Flierl Independent Researcher, Berlin, Germany At the first meeting in Zurich I said right away that I could not imagine a Congress without the participation of the Russians. Letter by Sigfried Giedion to El Lissitzky. 21 May 1928. GTA archive. Zurich The paper deals with the dramatic story of the preparation for (and subsequent failure of) the 4th Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne (CIAM) conference in Moscow. The offer to host the congress in Moscow was made in 1929, with the planned topic ‘Urban Organisation, Urban Construction, and Regional Planning’. Had it taken place in 1930 or 1931, the planned congress would have had an enormous impact. It probably would have been able to counteract the split of the modern urban construction movement into two factions, with those in favour of reconstructing existing cities on the one hand and proponents of building brand new cities on the other. It is widely believed that the congress was moved from Moscow to Athens due to CIAM’s protest against the results of the competition for the Palace of Soviets. Indeed, the controversy over this contest certainly delayed the congress. However, the study of the archival sources shows that the postponement was a result of a drastic change in the USSR’s domestic policies, which took place before CIAM challenged the results of the competition. -

Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism As a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union

Momentum Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 6 2018 Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Robert Levine University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum Recommended Citation Levine, Robert (2018) "Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union," Momentum: Vol. 5 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Architecture & Ideology: Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Abstract This paper examines the role of architecture in the promotion of political ideologies through the study of modern architecture in the 20th century. First, it historicizes the development of modern architecture and establishes the style as a tool to convey progressive thought; following this perspective, the paper examines Swedish Functionalism and Constructivism in the Soviet Union as two case studies exploring how politicians react to modern architecture and the ideas that it promotes. In Sweden, Modernism’s ideals of moving past “tradition,” embracing modernity, and striving to improve life were in lock step with the folkhemmet, unleashing the nation from its past and ushering it into the future. In the Soviet Union, on the other hand, these ideals represented an ideological threat to Stalin’s totalitarian state. This thesis or dissertation is available in Momentum: https://repository.upenn.edu/momentum/vol5/iss1/6 Levine: Modern Architecture & Ideology Modern Architecture & Ideology Modernism as a Political Tool in Sweden and the Soviet Union Robert Levine, University of Pennsylvania C'17 Abstract This paper examines the role of architecture in the promotion of political ideologies through the study of modern architecture in the 20th century. -

Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: an Ethnography of Design

The University of Manchester Research Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Yaneva, A. (2009). Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design. (1st ed.) 010 Publlishers. http://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Made_by_the_Office_for_Metropolitan_Arch.html?id=Z4okIn5RvHYChttp:// www.010.nl/catalogue/book.php?id=714 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design 010 Publishers Rotterdam 2009 Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design Albena Yaneva For Bruno Latour Acknowledgements 5 I would like to thank my publisher for encouraging me to systematically explore the large pile of interviews and ethnographic materials collected during my participant observation in the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam (oma) in the period 2002-4. -

Boym 1. Model for the Monument to the Third International, November

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS boym 1. Model for The Monument to the Third International, November 1920 62 2. Vladimir Tatlin, trying Letatlin (Moscow, 1932) 67 3. Sketch for the set decoration of Chalice of Joy (1949–50) 68 4. Vladimir Tatlin, White Jar and Potato (1948–51) 69 5. Vladimir Tatlin, A Skull on the Open Book (1948–53) 69 6. Model of Tatlin’s Tower 70 7. Constantin Boym, Palace of the Soviets and Tatlin’s Tower (1996) 71 8. Leonid Sokov, Moscow Yard 72 9. Leonid Sokov, Watchtower: Self-portrait as a Soldier 74 10. Leonid Sokov, Ur-Neo-Geo Tower 74 11. Yuri Avvakumov, Perestroika Tower (1990) 76 12. Ilya Kabakov, sketch for The Palace of the Projects (1999) 77 13. Ilya Kabakov, sketch for The Palace of the Projects (1999) 78 14. Svetlana Boym, ‘‘Return Home,’’ from Nostalgic Technologies 80 15. Tatlin’s Letatlin and Nabokov’s Butterfly from Hybrid Utopias (2003–6) 81 16. Tatlin’s Letatlin and Nabokov’s Butterfly from Hybrid Utopias (2003–6) 82 17. Tatlin’s Letatlin and Nabokov’s Butterfly from Hybrid Utopias (2003–6) 82 eshel 1. Deserted, cemented-up houses in Haifa’s Arab quarter 138 2. Igal Shtayim, Untitled 139 3. Nava Semel, ‘‘Le’vad’’ (Alone) 140 4. Facsimile of first page of Kluge, ‘‘Der Luftangri√ auf Halberstadt am 8. April 1945’’ 145 hell 1. Gustave Doré, The New Zealander 173 2. Adolf Hitler with the Italian king in Rome 184 3. The Mosaic Room in Albert Speer’s Chancellery, Berlin 187 beasley-murray 1. Vilcashuamán 218 2. -

TWO REGIMES, TWO UNIVERSITY CITIES Architectonic Language and Ideology in Lithuania and Portugal: 1930-1975

TWO REGIMES, TWO UNIVERSITY CITIES Architectonic language and ideology in Lithuania and Portugal: 1930-1975 Neringa Sobeščukaitė Dissertation of the Integrated Master’s Degree in Architecture supervised by Professor Nuno Alberto Leite Rodrigues Grande Department of Architecture, FCTUC, July 2013 TWO REGIMES, TWO UNIVERSITY CITIES Architectonic language and ideology in Lithuania and Portugal: 1930-1975 The author would like to thank numerous persons for their varied help, advice and encouragement, without whom research on this subject would have been impossible, if not at least much less comfortable or entertain- ing. These persons include but are not limited by colleagues from Kaunas Art Faculty of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts and Department of Architecture of the University of Coimbra. In particular, the author would like to thank: Miguel Godinho, Pedro Silva, João Briosa, Theresa Büscher, Monika Intaitė, Joana Orêncio, Lara Maminka Borges, Vânia Simões, Nuno Nina Martins, Magdalena Mozūraitytė, Jautra Bernotaitė, and Andrius Ropolas, for their support, and helpful hints along the way. The specificity of this work would not have been possible without the personal experience and academic for- mation in two institutions: Kaunas Art Faculty of the Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts, the university where the author finished its Bachelor degree, and Department of Architecture of the University of Coimbra, the current place of studies of the author. In this contex, the author would like to express the deepest gratitude to all pro- fessors and colleagues, for their help and support, for their brief discussions to deep, sometimes all night long conversations, that helped to feel at home, even when being half-way across the world. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Current Academic Appointments 1995- Professor in Practice of Architecture and Urban Design, Harvard University Graduate School of Design Education 1972 Diploma in Architecture, Architectural Association, London Academic Experience 1990-95 Arthur Rotch Adjunct Professor of Architecture, Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1991-92 Professor of Architecture, Rice University, Houston, Texas 1988-89 Professor of Architecture, Technical University, Delft, Holland 1976 Architectural Association, London, England 1975 University of California, Los Angeles School of Architecture 1975 Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York Professional Experience 1975- Principal, Office for Metropolitan Architecture Selected Realizations 2003 Headquarters for Central Chinese Television (CCTV) in Beijing Netherlands Embassy, Berlin 2001 Prada store New York, USA Guggenheim Exhibition Hall, Las Vegas, USA Guggenheim Hermitage, Las Vegas, USA 1999 2nd Stage Theatre, New York, USA 1998 Maison à Bordeaux, France 1997 Educatorium, Utrecht, Netherlands 1994 Lille Grand Palais, Lille, France Euralille Masterplan, Lille, France 1993 Dutch House, Holland 1992 Kunsthal, Rotterdam, Holland 1991 Villa dall'Ava, Paris, France Nexus Housing, Fukuoka, Japan Byzantium, Amsterdam, Netherlands 1989 Patio Villa, Rotterdam, Holland 1987 Netherlands Dance Theatre, The Hague, Holland Work in Progress 2001 Extension LACMA, LA, USA Dallas multi form theatre, Dallas, USA Zeche Zollverein Masterplan, Essen, Germany Cordoba Conference Centre, Cordoba,