Wonder Woman: an Assemblage of Complete Virtue Packed in a Tight Swimsuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

THE DECAY of LYING Furniture of “The Street Which from Oxford Has Borrowed Its by OSCAR WILDE Name,” As the Poet You Love So Much Once Vilely Phrased It

seat than the whole of Nature can. Nature pales before the THE DECAY OF LYING furniture of “the street which from Oxford has borrowed its BY OSCAR WILDE name,” as the poet you love so much once vilely phrased it. I don’t complain. If Nature had been comfortable, mankind would A DIALOGUE. never have invented architecture, and I prefer houses to the open Persons: Cyril and Vivian. air. In a house we all feel of the proper proportions. Everything is Scene: the library of a country house in Nottinghamshire. subordinated to us, fashioned for our use and our pleasure. Egotism itself, which is so necessary to a proper sense of human CYRIL (coming in through the open window from the terrace). dignity, is entirely the result of indoor life. Out of doors one My dear Vivian, don’t coop yourself up all day in the library. It becomes abstract and impersonal. One’s individuality absolutely is a perfectly lovely afternoon. The air is exquisite. There is a leaves one. And then Nature is so indifferent, so unappreciative. mist upon the woods like the purple bloom upon a plum. Let us Whenever I am walking in the park here, I always feel that I am go and lie on the grass, and smoke cigarettes, and enjoy Nature. no more to her than the cattle that browse on the slope, or the VIVIAN. Enjoy Nature! I am glad to say that I have entirely lost burdock that blooms in the ditch. Nothing is more evident than that faculty. People tell us that Art makes us love Nature more that Nature hates Mind. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

Wonder Woman & Associates

ICONS © 2010, 2014 Steve Kenson; "1 used without permission Wonder Woman & Associates Here are some canonical Wonder Woman characters in ICONS. Conversation welcome, though I don’t promise to follow your suggestions. This is the Troia version of Donna Troy; goodness knows there have been others.! Bracers are done as Damage Resistance rather than Reflection because the latter requires a roll and they rarely miss with the bracers. More obscure abilities (like talking to animals) are left as stunts.! Wonder Woman, Donna Troy, Ares, and Giganta are good candidates for Innate Resistance as outlined in ICONS A-Z.! Acknowledgements All of these characters were created using the DC Adventures books as guides and sometimes I took the complications and turned them into qualities. My thanks to you people. I do not have permission to use these characters, but I acknowledge Warner Brothers/ DC as the owners of the copyright, and do not intend to infringe. ! Artwork is used without permission. I will give attribution if possible. Email corrections to [email protected].! • Wonder Woman is from Francis Bernardo’s DeviantArt page (http://kyomusha.deviantart.com).! • Wonder Girl is from the character sheet for Young Justice, so I believe it’s owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Troia is from Return of Donna Troy #4, drawn by Phil Jimenez, so owned by Warner Brothers/DC.! • Ares is by an unknown artist, but it looks like it might have been taken from the comic.! • Cheetah is in the style of Justice League Unlimited, so it might be owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Circe is drawn by Brian Hollingsworth on DeviantArt (http://beeboynyc.deviantart.com) but coloured by Dev20W (http:// dev20w.deviantart.com)! • I got Doctor Psycho from the Villains Wikia, but I don’t know who drew it. -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh the Asian Conference on Arts

Diminished Power: The Fall of Wonder Woman Ahmed Bhuiyan, Independent Researcher, Bangladesh The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2015 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most recognized characters that has become a part of the pantheon of pop- culture is Wonder Woman. Ever since she debuted in 1941, Wonder Woman has been established as one of the most familiar feminist icons today. However, one of the issues that this paper contends is that this her categorization as a feminist icon is incorrect. This question of her status is important when taking into account the recent position that Wonder Woman has taken in the DC Comics Universe. Ever since it had been decided to reset the status quo of the characters from DC Comics in 2011, the character has suffered the most from the changes made. No longer can Wonder Woman be seen as the same independent heroine as before, instead she has become diminished in status and stature thanks to the revamp on her character. This paper analyzes and discusses the diminishing power base of the character of Wonder Woman, shifting the dynamic of being a representative of feminism to essentially becoming a run-of-the-mill heroine. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org One of comics’ oldest and most enduring characters, Wonder Woman, celebrates her seventy fifth anniversary next year. She has been continuously published in comic book form for over seven decades, an achievement that can be shared with only a few other iconic heroes, such as Batman and Superman. Her greatest accomplishment though is becoming a part of the pop-culture collective consciousness and serving as a role model for the feminist movement. -

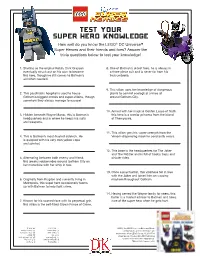

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge How well do you know the LEGO® DC Universe™ Super Heroes and their friends and foes? Answer the trivia questions below to test your knowledge! 1. Starting as the original Robin, Dick Grayson 8. One of Batman’s oldest foes, he is always in eventually struck out on his own to become a three-piece suit and is never far from his this hero, though he still comes to Batman’s trick umbrella. aid when needed! 9. This villain uses her knowledge of dangerous 2. This psychiatric hospital is used to house plants to commit ecological crimes all Gotham’s biggest crooks and super-villains, though around Gotham City. somehow they always manage to escape! 10. Armed with her magical Golden Lasso of Truth, 3. Hidden beneath Wayne Manor, this is Batman’s this hero is a warrior princess from the island headquarters and is where he keeps his suits of Themyscira. and weapons. 11. This villain gets his super-strength from the 4. This is Batman’s most-trusted sidekick. He Venom-dispensing mask he constantly wears. is quipped with his very own yellow cape and symbol. 12. This base is the headquarters for The Joker and The Riddler and is full of booby traps and 5. Alternating between both enemy and friend, sinister rides. this jewelry robber rides around Gotham City on her motorbike with her whip in tow. 13. Once a psychiatrist, this villainess fell in love with the Joker and joined him on causing 6. Originally from Krypton and currently living in mayhem throughout Gotham. -

Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Literary Anglo-Saxon

ENVIRONMENTAL HUMANITIES IN PRE-MODERN CULTURES Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Heide Estes Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Environmental Humanities in Pre‑modern Cultures This series in environmental humanities offers approaches to medieval, early modern, and global pre-industrial cultures from interdisciplinary environmental perspectives. We invite submissions (both monographs and edited collections) in the fields of ecocriticism, specifically ecofeminism and new ecocritical analyses of under-represented literatures; queer ecologies; posthumanism; waste studies; environmental history; environmental archaeology; animal studies and zooarchaeology; landscape studies; ‘blue humanities’, and studies of environmental/natural disasters and change and their effects on pre-modern cultures. Series Editor Heide Estes, University of Cambridge and Monmouth University Editorial Board Steven Mentz, St. John’s University Gillian Overing, Wake Forest University Philip Slavin, University of Kent Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination Heide Estes Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: © Douglas Morse Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Layout: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 944 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 838 7 doi 10.5117/9789089649447 nur 617 | 684 | 940 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The author / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2017 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Wonder Woman by John Byrne Vol. 1 1St Edition Kindle

WONDER WOMAN BY JOHN BYRNE VOL. 1 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Byrne | 9781401270841 | | | | | Wonder Woman by John Byrne Vol. 1 1st edition PDF Book Diana met the spirit of Steve Trevor's mother, Diana Trevor, who was clad in armor identical to her own. In the s, one of the most celebrated creators in comics history—the legendary John Byrne—had one of the greatest runs of all time on the Amazon Warrior! But man, they sure were not good. Jul 08, Matt Piechocinski rated it really liked it Shelves: graphic-novels. DC Comics. Mark Richards rated it really liked it Mar 29, Just as terrifying, Wonder Woman learns of a deeper connection between the New Gods of Apokolips and New Genesis and those of her homeland of Themyscira. Superman: Kryptonite Nevermore. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. There's no telling who will get a big thrill out of tossing Batman and Robin Eternal. This story will appear as an insert in DC Comics Presents A lot of that is probably due to a general dislike for the 90s style of drawing superheroes, including the billowing hair that grows longer or shorter, depending on how much room there is in the frame. Later, she rebinds them and displays them on a platter. Animal Farm. Azzarello and Chiang hand over the keys to the Amazonian demigod's world to the just-announced husband-and-wife team of artist David Finch and writer Meredith Finch. Jun 10, Jerry rated it liked it.