Gender Perspective in Telangana Armed Struggle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Category Wise Provisional Merit List of Eligible Students Subject to Verification of Documents for the Grant of Pragati Scholarship Scheme(Degree) 2018-19 (1St Year)

Category wise Provisional Merit List of eligible students subject to verification of documents for the Grant of Pragati Scholarship Scheme(Degree) 2018-19 (1st year) Pragati (Degree)-Nos. of Schlarships-2000 Categor Number of Sl. No. Merit No. ies Students 1 Open 0001-1010 1010 2 OBC 1020-2091 540 3 SC 1019-4474 300 4 ST 1304-6148 90 Pragati open category merit list for the academic year 2018-19(1st yr.) Degree Sl. No. Merit Caste Student Student Father Name Course Name AICTE Institute Institute Name Institute District Institute State No. Category Unique Id Name Permanent ID 1 1 OPEN 2018020874 Gayathri M Madhusoodanan AGRICULTURAL 1-2886013361 KELAPPAJI COLLEGE OF MALAPPURAM Kerala Pillai Pillai K G ENGINEERING AGRICULTURAL ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, TAVANUR 2 2 OPEN 2018014063 Sreeyuktha ... Achuthakumar K CHEMICAL 1-13392996 GOVERNMENTENGINEERINGCO THRISSUR Kerala R ENGINEERING LLEGETHRISSUR 3 3 OPEN 2018015287 Athira J Radhakrishnan ELECTRICAL AND 1-8259251 GOVT. ENGINEERING COLLEGE, THIRUVANANTHAP Kerala Krishnan S R ELECTRONICS BARTON HILL URAM ENGINEERING 4 4 OPEN 2018009723 Preethi S A Sathyaprakas ARCHITECTURE 1-462131501 COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE THIRUVANANTHAP Kerala Prakash TRIVANDRUM URAM 5 5 OPEN 2018003544 Chaithanya Mohanan K K ELECTRONICS & 1-13392996 GOVERNMENTENGINEERINGCO THRISSUR Kerala Mohan COMMUNICATION LLEGETHRISSUR ENGG 6 6 OPEN 2018015493 Vishnu Priya Gouravelly COMPUTER SCIENCE 1-12344381 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF HYDERABAD Telangana Gouravelly Ravinder Rao AND ENGINEERING ENGINEERING 7 7 OPEN 2018011302 Pavithra. -

Discourses of Merit and Agrarian Morality in Telugu Popular Cinema

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Looking Back at the Land: Discourses of Agrarian Morality in Telugu Popular Cinema and Information Technology Labor Padma Chirumamilla School of Information, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA This article takes Anand Pandian’s notion of “agrarian civility” as a lens through which we can begin to understand the discourses of morality, merit, and exclusivity that color both popular Telugu film and Telugu IT workers’ understanding of their technologically enabled work. Popular Telugu film binds visual qualities of the landscape and depictions of heroic technological proficiency to protagonists’ internal dispositions and moralities. I examine the portrayal of the landscape and of technology in two Telugu films: Dhee … kotti chudu,and Nuvvostanante Nenoddantana, in order to more clearly discern the nature of this agrarian civility and—more importantly for thinking about Telugu IT workers— to make explicit its attribution of morality to “merit” and to technological proficiency. Keywords: Information Technology, Morality, Telugu Cinema, Merit, Agrarian Civility. doi:10.1111/cccr.12144 InachasesceneinthepopularTelugufilmDhee … kotti chudu,anameless gangster—having just killed off his rival’s family—is fleeing to Bangalore from Hyderabad, driving along roads surrounded by rocky, barren outcrops, and shriveled patches of trees. The rival’s boss confronts him unexpectedly on the deserted road, quickly and seemingly instantaneously surrounding him with his own men and vehicles, before killing him in retaliation. The film then quickly moves on to its main character, a rather comedic scam artist, and its main spaces, in the city of Hyderabad.1 This particular stretch of barren landscape—scene to the violence that underlies a significant revenge plot woven into the film’s story—is not returned to. -

Twenty Years of CRC Years Twenty Rrrrrrr Rrrr Eeeee Tttttttttt Centre for Child Rights

Twenty Years of CRC A Balance Sheet Twenty Years of CRC Years A BALANCE SHEET VOLUME II of CRC – A Balance Sheet Volume II Centre II for Child Rights terre des hommes Cover 1.indd Spread 1 of 2 - Pages(2, 3) 11/16/2011 6:22:03 PM Twenty Years of CRC A Balance Sheet Volume II i HAQ: Centre for Child Rights 2011 ISBN 978-81-906548-7-6 Any part of this report may be reproduced with due acknowledgement and citation. Disclaimer: CRC20BS Collective does not subscribe to disclosure of identity of victims of abuse as carried in the media reports used in this publication. Published by: CRC20BS COLLECTIVE C/o HAQ: Centre for Child Rights B 1/2, Ground Floor, Malviya Nagar New Delhi 110017 INDIA T 91-11-26677412 F 91-11-26674688 E [email protected] www.haqcrc.org Supported by: terre des hommes Germany Research and Compilation: Bharti Ali and Praveena Nair S Cover photo: Mikhail Esteves Design and Printing: Aspire Design ii Acknowledgements Last one and a half years has been the most happening period for HAQ: Centre for Child Rights. What began as an initiative requiring inputs every now and then turned into full-time occupation as HAQ came to be nominated for coordinating the twenty-year audit of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in India. HAQ thus became a proud member of what gradually came to be known as the CRC20BS Collective. HAQ: Centre for Child Rights is grateful to all the Steering Committee and Organising Committee members of CRC20BS Collective for vesting their faith in us and their continuous support throughout the audit process. -

A Perspective on Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy's

Vol.2 No. 3 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 A PERSPECTIVE ON BHIMIREDDY NARSIMHA REDDY’S ROLE IN TELANGANA ARMED STRUGGLE (1946-51) Dr. Gugulothu Ravi Lecturer, Department of History, Acharya Degree College, Warangal, Telangana, India Abstract Comrade Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy was a freedom fighter and a leader of the Telangana Rebellion, fighting for the liberation of the Telangana region of Hyderabad State from the oppressive rule of the Nizam. He belonged to Suryapet district of today's Telangana. B.N.Reddy, as he was known, fought the Razakars during the Nizam’s rule for six years by being underground. He escaped 10 attempts on his life, prominent among them being an attack against him, his wife and infant son by the Razakars near Mahbubabad in Warangal district. Narsimha Reddy broke the army cordon while exchanging fire and escaped. He also carried out struggles against feudal oppression and bonded labour. Renowned across Telangana with his simple name of BN, he is none other than Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy. Those were the days during which the poor people of Telangana suffered inexplicable exploitation at the hand of the Landlords and toiled as slaves without an iota of freedom He thought that socialism was the ultimate system for the safety of mankind. With the entry into armed struggle he fought against the Nizam’s rule and in a free society he aspired to provide food, shelter, employment for the poor people of Telangana. Keywords: Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy’s role in Telangana Armed Struggle Introduction atrocities of the Nizam and need for a struggle against his Telangana Armed Struggle was a historical and a tyranny. -

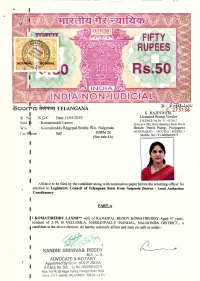

Komatireddy Laxmi Set 1.Pdf

}c· R~.A-<.J £@ dt1·.IHI TELANGANA K. RAJESWA~I 2 B 91 . N~: >5S' Date.ll/0S/2019 Licenced Stamp Vendor LICENCE No.16 -II -43/2017 Sold'fl : Komatireddy Laxmi H.No.6-3-382, Near Himalaya Book World W10. : Komatireddy Rajgopal Reddy, RJo. Nalgonda. Beside Petrol Pump, Punjagutta For~10m Self FORM 26 HYDERABAD (SOUTH) DISTRICT (See rule 4A) Mobile No:+91-8686669973 I. ,I ,I Affidavit to be filed by the candidate along with nomination paper before the returning officer for election to Legislative Council of Telangana State from Nalgonda District - Local Authorities . Constituency PART-A II KOMATIREDDY LAXMI** wife of RAJGOPAL REDDY KOMATIREDDY Aged 47 years, resident of 2-19, B VELLEMLA, NARKETPALLY MANDAL, NALGONDA DISTRICT., a Icandidate at the above.election, do hereby solemnly affirm and state on oath as under:- I \~\\_, i \~ 1 SANDHI SR!NIVAS REDOV M.A., LL.B., i ADVOCATE s NOTARY • Appointed by Govt. of A.P INDIA I G.O.M.S. No. 385, Lr. No. NRi1981212011 R€3i: 7-8-74, Sri Nagar Colony, P"dnagalRoad. NLG. I Office: S.PT Market, N.A.LGONDA- 508 001 (AP) (1) I am a candidate set up by INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS PARTY(** name of the political party) f** am Gontestingas an Independent candidate. (** strike out whichever is not applicable) (2) My name is enrolled in Nakrekal Assemhly(95), Telangana State (Name of the constituency and the State), at Serial No.136 in Part No 160 with EPIC No.WPI0344309 (3) My contact telephone number (s) is fare 9849211221 (Mobile), 040-23606068 (Landline) and my e-mail id is iaxmikomatireddv99(wgmail.q)111 and my social media accounts are .. -

Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science

A STUDY OF ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION OF BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY IN UTTAR PRADESH SINCE 1996 Thesis Submitted For the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science By Mohammad Amir Under The Supervision of DR. MOHAMMAD NASEEM KHAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) Department Of Political Science Telephone: Aligarh Muslim University Chairman: (0571) 2701720 AMU PABX : 2700916/27009-21 Aligarh - 202002 Chairman : 1561 Office :1560 FAX: 0571-2700528 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. Mohammad Amir, Research Scholar of the Department of Political Science, A.M.U. Aligarh has completed his thesis entitled, “A STUDY OF ELECTORAL PARTICIPATION OF BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY IN UTTAR PRADESH SINCE 1996”, under my supervision. This thesis has been submitted to the Department of Political Science, Aligarh Muslim University, in fulfillment of requirement for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. To the best of my knowledge, it is his original work and the matter presented in the thesis has not been submitted in part or full for any degree of this or any other university. DR. MOHAMMAD NASEEM KHAN Supervisor All the praises and thanks are to almighty Allah (The Only God and Lord of all), who always guides us to the right path and without whose blessings this work could not have been accomplished. Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to Late Prof. Syed Amin Ashraf who has been constant source of inspiration for me, whose blessings, Cooperation, love and unconditional support always helped me. May Allah give him peace. I really owe to Prof. -

STATISTICAL REPORT GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1998 the 12Th LOK

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1998 TO THE 12th LOK SABHA VOLUME II (CONSTITUENCY DATA - SUMMARY) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1998 (12th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME II (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 5 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 6 - 548 Election Commission of India-General Elections, 1998 (12th LOK SABHA) LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP BHARATIYA JANATA PARTY 2 . BSP BAHUJAN SAMAJ PARTY 3 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 4 . CPM COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 5 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 6 . JD JANATA DAL 7 . SAP SAMATA PARTY STATE PARTIES 8 . AC ARUNACHAL CONGRESS 9 . ADMK ALL INDIA ANNA DRAVIDA MUNNETRA KAZHAGAM 10 . AGP ASOM GANA PARISHAD 11 . AIIC(S) ALL INDIA INDIRA CONGRESS (SECULAR) 12 . ASDC AUTONOMOUS STATE DEMAND COMMITTEE 13 . DMK DRAVIDA MUNNETRA KAZHAGAM 14 . FBL ALL INDIA FORWARD BLOC 15 . HPDP HILL STATE PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC PARTY 16 . HVP HARYANA VIKAS PARTY 17 . JKN JAMMU & KASHMIR NATIONAL CONFERENCE 18 . JMM JHARKHAND MUKTI MORCHA 19 . JP JANATA PARTY 20 . KEC KERALA CONGRESS 21 . KEC(M) KERALA CONGRESS (M) 22 . MAG MAHARASHTRAWADI GOMANTAK 23 . MNF MIZO NATIONAL FRONT 24 . MPP MANIPUR PEOPLE'S PARTY 25 . MUL MUSLIM LEAGUE KERALA STATE COMMITTEE 26 . NTRTDP(LP) NTR TELUGU DESAM PARTY (LAKSHMI PARVATHI) 27 . PMK PATTALI MAKKAL KATCHI 28 . RPI REPUBLICAN PARTY OF INDIA 29 . RSP REVOLUTIONARY SOCIALIST PARTY 30 . SAD SHIROMANI AKALI DAL 31 . SDF SIKKIM DEMOCRATIC FRONT 32 . -

Investor Factsheet CIN: L24110AP2005PLC045726

Sree Rayalaseema High-Strength Hypo Ltd Investor Factsheet CIN: L24110AP2005PLC045726 STOCK PROFILE ABOUT US Commodity . Sree Rayalaseema Hi-Strength Hypo Limited is an India-based manufacturer Sector Chemicals of both organic and inorganic chemicals. The Company is engaged in manufacturing and sale of industrial chemicals, generation & distribution of SRHHYPOLTD/ NSE/BSE power and coal trading. 532842 . It operates through two segments: Chemicals and Power generation. The Incorporated 2005 Company generates power through wind and thermal. It has three state-of-art plants located at Andhra Pradesh and Its windmill Issued shares (mn) 17.16 power units are situated in Tamil Nadu. Share Price* 105.25 SEGMENT OVERVIEW Market Cap*(Rs.mn) 1806.0 52 Week High/Low 189.0-88.2 Water Treatment Chemicals 50.4% *As on 14st NOVEMBER 2019 SHAREHOLDING PATTERN (%) Sulphuric Acid 20.6% Promoter 61.78% Public 38.22% As on September 2019 Coal Trading 14.4% VALUATIONS EV/Sales 0.28x Others (Power generation, Sodium EV/EBITDA 2.05x methoxide, Sodium hydride) 14.6% P/E 14.3x As on March 2019 Financial Highlights Sales (Rs. cr) EBITDA (Rs. cr) PAT (Rs. cr) 36.6 702.1 25.0 550.5 98.3 19.4 18.4 20.4 392.4 363.5 391.0 38.5 42.3 47.8 45.8 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 Debt to Equity (x) ROE (%) ROCE (%) 0.4 0.3 13.4% 13.2% 11.3% 15.3% 0.2 0.2 8.4% 12.3% 13.5% 0.1 6.4% 8.8% 8.7% FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 ShreeFY15 RayalaseemaFY16 FY17 High-StrengthFY18 FY19 Hypo FY15 FY16 FY17 FY18 FY19 Ltd | Factsheet - FY19 Sree Rayalaseema High-Strength Hypo Ltd Investor Factsheet CIN: L24110AP2005PLC045726 Awards Product Applications Aquaculture, textile, leather, paper and sugar Water treatment industries, Textile Industries, Purification of Chemicals Drinking Water, Sanitation of Swimming Pools, Meat etc. -

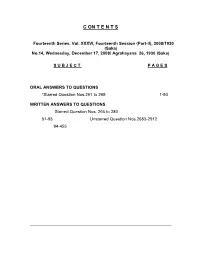

C on T E N T S

C ON T E N T S Fourteenth Series, Vol. XXXVI, Fourteenth Session (Part-II), 2008/1930 (Saka) No.14, Wednesday, December 17, 2008/ Agrahayana 26, 1930 (Saka) S U B J E C T P A G E S ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS *Starred Question Nos.261 to 265 1-50 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question Nos. 266 to 280 51-93 Unstarred Question Nos.2683-2912 94-455 * The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 456-491 MESSAGES FROM RAJYA SABHA 492-493 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE 19th and 20th Reports 494 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE 78th to 80th Reports 494 COMMITTEE ON PETITIONS 43rd to 45th Reports 495 STANDING COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT 212th Report 496 STATEMENT BY MINISTERS 497-508 (i) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 70th Report of the Standing Committee on Finance on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Shri G.K. Vasan 497-499 (ii) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 204th Report of the Standing Committee on Human Resource Development on Demands for Grants (2007-08), pertaining to the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. Dr. M.S. Gill 500 (iii) Status of implementation of the (a) recommendations contained in the 23rd Report of the Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law and Justice on the Government's policy of appointment on compassionate ground, pertaining to the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions (b) Status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the 189th Report of the Standing Committee on Science and Technology, Environment and Forests on Demands for Grants (2008-09), pertaining to the Department of Space. -

![List of Political Parties in India ]]National Political Parties](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1574/list-of-political-parties-in-india-national-political-parties-2051574.webp)

List of Political Parties in India ]]National Political Parties

List of political parties in India ]]National political parties Party Abbreviation General Secretary / President Nationalist Congress Party NCP Sharad Pawar Indian National Congress INC Sonia Gandhi Bharatiya Janata Party BJP Nitin Gadkari Communist Party of India CPI Suravaram Sudhakar Reddy Communist Party of India (Marxist) CPI(M) Prakash Karat Source: Election Commission of India[2] [[edit]]State political parties (State wise list) Political State Party name Election symbol Abbr. Alliance Lok Satta Party Whistle LSP Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen Kite AIMIM Andhra Pradesh Telangana Rashtra Samithi Car TRS NDA Telugu Desam Party Bicycle TDP Third Front Arun Khitoliya National Party cealing Fan YSRCP All India United Democratic Front Lock & Key Assam Asom Gana Parishad Elephant NDA Bodoland People's Front Nangol UPA Janata Dal (United) Arrow JD(U) NDA Bihar raman party Bungalow LJP Rashtriya Janata Dal Hurricane Lamp RJD Fourth Front ZGE Goa Map Goa Save Goa Front Aeroplane Haryana Janhit Congress (BL) Tractor HJC NDA Haryana Indian National Lok Dal Eyeglasses INLD Jammu & Kashmir National Plough UPA Conference Jammu & Jammu & Kashmir National Bicycle Kashmir Panthers Party Jammu and Kashmir Peoples Ink Pot & Pen Democratic Party Jharkhand AJSU Party Banana Jharkhand Mukti Morcha Bow & Arrow JMM NDA Jharkhand Vikas Morcha Comb NDA (Prajatantrik) Rashtriya Janata Dal Hurricane Lamp RJD Fourth Front A Lady Farmer carrying Paddy Janata Dal (Secular) JD(S) on her head Karnataka Janata Party KJP Karnataka BSR Congress Kannada Chalavali Vatal -

Title: Need to Withdraw the Proposal to Establish Field Firing Range in Rachakonda in Andhra Pradesh

an> Title: Need to withdraw the proposal to establish Field Firing Range in Rachakonda in Andhra Pradesh. Shri SURAVARAM SUDHAKAR REDDY (NALGONDA): At present there is a Defence Field Firing Range in the Medchal village, nearer to Hyderabad. Because the city has grown, so that, village is almost merged into city. In this scenario, it is quite likely to shift Field Firing Range. It is reported that they have chosen Rachakonda area of Narayanpur Mandal, Bhongir Revenue division. Also some area of Ibrahimpatnam constituency of Ranga Reddy District is also included. This whole area is a part of my parliamentary constituency. It is learnt that some government land and some PVT land is going to be acquired for this purpose. Most of the proposed land is under cultivation of local tribals and poor people. All local people, local panchayath, local pubic representatives, MP, MLA, all party joint action committees are opposing this proposal. Under JNURM Government is proposing to develop basic infrastructure upto 100 kms around the city. As Rachakonda is below 35-40 kms, this whole area is likely to get developed within another 15-20 years. Then again Government has to search for new Firing Range. And also there are past experience, in Medchal Firing Range, that being a place of high mobility, many people and domestic animals were killed by the bullets came outside the Firing Range. So, this is not safe for the people here in Rachakonda due to increasing density of mobility. By keeping all this facts in view, the proposal of establishing Field Firing Range in Rahakonda should be withdrawn. -

Lok Sabha Debates Lok Sabha Members Sworn Obituary References

LOK SABHA DEBATES ----. LOK SABHA till 1969. He was deeply devoted to Parliamentary institutions and made a very distinguished Monday, June 10,1996/ Jyalstha 20, 19 18 (Saka) contribution as Presiding Officer In form of decisions and rulings from the Chair. (The Lok Sabha met at Eleven of the Clock) A widely travelled person, he headed many [MR. SPEAKERin the Chair] Parliamentary delegations to various countries. He was again elected to the Slxth Lok Sabha in 1077 MEMBERS SWORN and re-elected Speaker of the Slxth Lok Sabha during the same year. However, he was destined to Shri Bommagani Dharma Biksham (Nalgonda) have greater attainments. Shri Ghulam Rasool Kar (Baramulla) In July, 1977, on his being chosen as the Shri G.M. Mir Magami (Srinagar) President of India, his long and illustrious public Shri Mohammad Maqbool Dar (Anantnag) career reached Its zenith. Through hls administraltvo Shri P. Namgyal (Ladakh) acumen, he added dignity to this office. A man who Prof. Chaman Lal Gupta (Udhampur) rose from humble means, displayed throughout hls public ilfe an abiding commitment to the welfare of Shri Mangat Ram Sharma (Jammu) the people. His skill in handling the tortuous political Shri Shivanand Hemappa Koujalgi (Belgaum) and administrative situations of the time is an ample testimony of his innate qualltles, astuteness and equipoise in the moments of stress and crisis. 11.10 hrs. His amiable disposition and genial informality OBITUARY REFERENCES earned him accolades. Even after he retired from the august Office of the President of India, his sage Demise of former President Dr. Neelam Sanjlva counsel served as a beacon in the troubled times.