Reviled Until Recently, Academic Art Is Being Revalued, and a Museum Inspired by a Mystical Beirut Collector Is Helping to Show the Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Art, Classic and Contemporary, Painting and Sculpture

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08191162 4 Virt-*'.', FRENCH ART THE HEW YORK PDBLIC LIB4^ARY ASTOK, LENOX Tli-DEN FOUNDATIONS / / "W Y( J SCRIB] 1 90J NG THE DAWN / FRENCH ART CLASSIC AND CONTEMPORARY PAINTING AND SCULPTURE BY W. C. BROWNELL NEW AND ENLARGED EDITION WITH FORTY-EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1901 COPYRIGHT, 1892, 1901, BY CHARLES SCRIBNEr's SONS PUBLISHED OCTOBER, 1901 THE NEW r, yc>^Y "y BUG LIBRARY ' ' i "» —f A S< » , TILBSN Pi»-JNBATIO«« D. B. UPDIKE, THE MERRYMOUNT PRESS, BOSTON TO AUGUSTE RODIN Advantage has been taken of the present ilkistrated edition of this book to add a chapter on "Rodin and the Institute," in which the progress of what ten years ago was altogether a "new movement in sculpture," is further considered. Except in sculpture, and in the sculpture of Rodin and that more or less directly in- fluenced by him, thei-e has been no new phase of French art developed within the decade — at least none important enough to impose other additions to the text of a work so general in character. CONTENTS I. CLASSIC PAINTING 1 I. CHARACTER AND ORIGIN II. CLAUDE AND POUSSIN III. LEBRUN AND LESUEUR IV. LOUIS QUINZE V. GREUZE AND CHARDIN VI. DAVID, INGRES, AND PRUDHON II. ROMANTIC PAINTING 39 I. ROMANTICISM II. GERICAULT AND DELACROIX III. THE FONTAINEBLEAU GROUP IV. THE ACADEMIC PAINTERS V. COUTURE, PUVIS DE CHAVANNES, AND REGNAULT III. REALISTIC PAINTING 75 I. REALISM II. COURBET AND BASTIEN-LEPAGE III. THE LANDSCAPE PAINTERS ; FROMENTIN AND GUILLAUMET IV. HISTORICAL AND PORTRAIT PAINTERS V. -

Art History and Visual Culture (AHVC) 1

Art History and Visual Culture (AHVC) 1 AHVC 204 - High Renaissance and Baroque Art & Architecture (4 Credit ART HISTORY AND VISUAL Hours) This course provides an introduction to the art, architecture, and selected CULTURE (AHVC) patterns of urban development Rome during the High Renaissance, Mannerism, and the Baroque era through the papacy of Alexander VII AHVC 096 - Senior Symposium (0 Credit Hours) (1655-67). Developments from ca. 1450 on in Rome leading to Julius II AHVC 101 - The Western World: Ancient to Baroque (4 Credit Hours) and the Roman High Renaissance will be a prime focus. Consideration This course is an introduction to selected themes, periods, and sites of of Mannerism, the Council of Trent and early Baroque visual and visual production and built practice in Europe, the Mediterranean, and architectural forms (later 16th century) will lead to the second focus on the New World. It focuses on a selected series of 'case studies' that 17th century visual and spatial practices in Counter-Reformation Rome integrate sites/monuments significant to the flow of Western art with and beyond. period-specific and general critical issues. The relation of systems of AHVC 210 - Special Topics in Ancient Medieval, and Early Modern Art in visual and architectural representation to period-specific and current the Mediterranean and Europe (4 Credit Hours) understandings of power, ritual, and the human body, as suggested AHVC 213 - Women Artists in the Movement (4 Credit Hours) through the disciplines of Art History and Visual Culture, will be key. The course will analyze artworks by Latina and Latin American women AHVC 131 - Asian Art and Visual Culture (4 Credit Hours) artists that address power inequalities within the intersections of class, An introduction to the art and visual culture of India, China, Japan and gender, and race. -

Why Art Cannot Be Taught

Why Art Cannot be Taught: A Handbook for Art Students James Elkins Teaching Art 2 1: Histories Table of Contents Introduction iii Chapter 1: Histories 1 Chapter 2: Conversations 61 Chapter 3: Theories -- Chapter 4: Critiques -- Chapter 5: Suggestions -- Chapter 6: Conclusions -- Index Teaching Art 3 1: Histories Introduction This little book is about the way studio art is taught. It’s a manual or survival guide, intended for people who are directly involved in college-level art instruction—both teachers and students—rather than educators, administrators, or theorists of various sorts. I have not shirked sources in philosophy, history, and art education, but I am mostly interested in providing ways for teachers and students to begin to make sense of the experience of learning art. The opening chapter is about the history of art schools. It is meant to show that what we think of as the ordinary arrangement of departments, courses, and subjects has not always existed. One danger of not knowing the history of art instruction, it seems to me, is that what happens in art classes begins to appear at timeless and natural. History allows us to begin to see the kinds of choices we have made for ourselves, and the particular biases and possibilities of our kinds of instruction. The second chapter, “Conversations,” is a collection of questions about contemporary art schools and art departments. It could have been titled “Questions Commonly Raised in Art Schools” or “Leading Issues in Art Instruction.” The topics include the following: What is the relation between the art department and other departments in a college? Is the intellectual isolation of art schools significant? What should be included in the first year program or the core curriculum for art students? What kinds of art cannot be learned in an art department? These questions recur in many settings. -

Context and the Half-Life of Romanticism Dr Steven Adams

Context and the half-life of romanticism Dr Steven Adams University of Hertfordshire, UK <[email protected]> I Introduction In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, many middle-class art lovers and art critics worried about the state of the arts in France. Two related anxieties can be identified. On the one hand were concerns about romantic artists and critics' repeated assertion of art's transcendental nature, the idea that it defied prescription, exegesis and rational explanation; on the other hand, was the anxiety expressed by conservative art critics and the public at large about the absence of a clear and authoritative template by which to make judgements about the arts. In this paper, I want to suggest these anxieties are historically connected to the position we find ourselves in today when we also search for some kind of critical template to assess where knowledge and value might be located within the arts and ask how that value might be expressed within the context of academic research. The assertion that there is a link between the art of the early-nineteenth and the early- twenty-first centuries is not as strained as it might first appear. An examination of the genealogy of modernism clearly shows a continuity between the conditions under which art was made, written about and consumed in the early-nineteenth century and some of the ways in which it was made, valorised and consumed in the recent past. Both then and now, the arts were/are popularly thought to be incomprehensible to the un-initiated; they are considered largely the domain of bohemians, and have no obvious social utility. -

Academicism to Modernism.Pdf

Academicism to Modernism Fresh Perspectives on Historic Indiana Art Academicism to Modernism Fresh Perspectives on Historic Indiana Art October 28, 2005 – May 21, 2006 William Weston Clarke Emison Museum of Art DePauw University Foreword Kaytie Johnson Essay and acknowledgements Laurette E. McCarthy Editor Vanessa Mallory FOREWORD DePauw University is pleased to present from their collections for the show: Dr. Stephen Academicism to Modernism: Fresh Perspectives Butler and Dr. Linda Ronald; the Jack D. Finley on Historic Indiana Art, an exhibition that focuses Collection; Indiana State Museum and Historic on the lesser-known and understudied aspects of Sites; Indianapolis Public Schools; the Richmond Indiana art from the late nineteenth through early Art Museum; the Sheldon Swope Art Museum; Judy twentieth centuries. A majority of exhibitions and Waugh; and Wishard Health Services. publications that focus upon this period tend to The contributions of several individuals have concentrate primarily on what is referred to as enabled DePauw to present this exhibition. My “Hoosier Impressionism,” – most notably paintings thanks go out to my dedicated staff – Christie by artists such as T.C. Steele, John Ottis Adams Anderson and Christopher Lynn – for their tireless and William Forsyth – which has perpetuated an energy and enthusiasm in bringing this show to incomplete, and exclusive, history of the artistic fruition. My appreciation is also extended to Kelly legacy of Indiana. By introducing our audience to Graves for her design expertise and assistance with works by unfamiliar – and familiar – artists, in a wide producing this publication, and to Vanessa Mallory, range of artistic styles, we hope to emphasize, and whose editing skills are unrivaled. -

Art Movements Referenced : Artists from France: Paintings and Prints from the Art Museum Collection

UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING ART MUSEUM 2009 Art Movements Referenced : Artists from France: Paintings and Prints from the Art Museum Collection OVERVIEW Sarah Bernhardt. It was an overnight sensation, and Source: www.wikipedia.org/ announced the new artistic style and its creator to The following movements are referenced: the citizens of Paris. Initially called the Style Mucha, (Mucha Style), this soon became known as Art Art Nouveau Les Nabis Nouveau. The Barbizon School Modernism Art Nouveau’s fifteen-year peak was most strongly Cubism Modern Art felt throughout Europe—from Glasgow to Moscow Dadaism Pointillism to Madrid — but its influence was global. Hence, it Les Fauves Surrealism is known in various guises with frequent localized Impressionism Symbolism tendencies. In France, Hector Guimard’s metro ART NOUVEau entrances shaped the landscape of Paris and Emile Gallé was at the center of the school of thought Art Nouveau is an international movement and in Nancy. Victor Horta had a decisive impact on style of art, architecture and applied art—especially architecture in Belgium. Magazines like Jugend helped the decorative arts—that peaked in popularity at the spread the style in Germany, especially as a graphic turn of the 20th century (1890–1905). The name ‘Art artform, while the Vienna Secessionists influenced art nouveau’ is French for ‘new art’. It is also known as and architecture throughout Austria-Hungary. Art Jugendstil, German for ‘youth style’, named after the Nouveau was also a movement of distinct individuals magazine Jugend, which promoted it, and in Italy, such as Gustav Klimt, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Stile Liberty from the department store in London, Alphonse Mucha, René Lalique, Antoni Gaudí and Liberty & Co., which popularized the style. -

Between Academic Art and Guild Traditions 21

19 JULIA STROBL, INGEBORG SCHEMPER-SPARHOLZ, quently accompanied Philipp Jakob to Graz in 1733.2 MATEJ KLEMENČIČ The half-brothers Johann Georg Straub (1721–73) and Franz Anton (1726–74/6) were nearly a decade younger. There is evidence that in 1751 Johann Georg assisted at BETWEEN ACADEMIC ART AND Philipp Jakobs’s workshop in Graz before he married in Bad Radkersburg in 1753.3 His sculptural œuvre is GUILD TRADITIONS hardly traceable, and only the figures on the right-side altar in the Church of Our Lady in Bad Radkersburg (ca. 1755) are usually attributed to him.4 The second half- brother, Franz Anton, stayed in Zagreb in the 1760s and early 1770s; none of his sculptural output has been confirmed by archival sources so far. Due to stylistic similarities with his brother’s works, Doris Baričević attributed a number of anonymous sculptures from the 1760s to him, among them the high altar in Ludina The family of sculptors Johann Baptist, Philipp Jakob, and the pulpit in Kutina.5 Joseph, Franz Anton, and Johann Georg Straub, who worked in the eighteenth century on the territory of present-day Germany (Bavaria), Austria, Slovenia, Cro- STATE OF RESEARCH atia, and Hungary, derives from Wiesensteig, a small Bavarian enclave in the Swabian Alps in Württemberg. Due to his prominent position, Johann Baptist Straub’s Johann Ulrich Straub (1645–1706), the grandfather of successful career in Munich awoke more scholarly in- the brothers, was a carpenter, as was their father Jo- terest compared to his younger brothers, starting with hann Georg Sr (1674–1755) who additionally acted as his contemporary Johann Caspar von Lippert. -

ART HISTORY for ARTISTS Interactions Between Scholarly Discourse and Artistic Practice in the 19Th Century

ART HISTORY FOR ARTISTS interactions between scholarly discourse and artistic practice in the 19th century 07 International Conference 08 organised by Eleonora Vratskidou Alexander von Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellow 09 Technische Universität Berlin July ART HISTORY FOR ARTISTS interactions between scholarly discourse and artistic practice in the 19th century Convenor | Concept : Eleonora Vratskidou Alexander von Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellow/Technische Universität Berlin ABSTRACTS Scientific Committee: Heinrich Dilly, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg Pascal Griener, Université de Neuchâtel Hubert Locher, Philipps-Universität Marburg Olga Medvedkova, CNRS-ENS (Centre Jean Pépin) Michela Passini, CNRS-ENS (IHMC) Matthew Rampley, University of Birmingham Bénédicte Savoy, Technische Universität Berlin Eleonora Vratskidou, Technische Universität Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Institut für Kunstwissenschaft und Historische Urbanistik Fachgebiet Kunstgeschichte der Moderne Berlin, July 7-9, 2016 Hauptgebäude - Technische Universität Berlin Straße des 17. Juni 135, 10623 Berlin Programme This conference Thursday July 7, 2016 H 3005 aims to explore the interactions 14.30 Registration Panel 2 and productive tensions Chair: Olga Medvedkova, CNRS-ENS 15.00 Eleonora Vratskidou between art practice and Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung/ 17.30 Pascal Griener Technische Universität Berlin Université de Neuchâtel art scholarship Introduction: Art history, Another wolf in the sheep yard: a discipline rooted in practice? David Sutter (1811-1880) -

The Romantic Age of English Painting

The Romantic Age • The Romantic period started in the eighteenth century but was at its peak between 1800 and 1850. Among the greatest Romantic painters were Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), JMW Turner (1775-1851), John Constable (1776-1837), and overseas, Francisco Goya (1746-1828), Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), Theodore Gericault (1791-1824) and Eugene Delacroix (1798-63). • The Romantic movement can be seen as a way of liberating human personality from the limitations of social convention and social morality. ‘Man is born free and everywhere is in chains’–Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). He later stated during a controversial essay that ‘Man is naturally good, and only by institutions is he made bad’. However, ‘The Social Contract’ was even more dangerous for it advocated democracy and denied the divine right of kings: thus bringing Rousseau a storm of social condemnation. Romantics: • Value emotions. Romanticism regards intense emotions as providing an authentic source of aesthetic experience and social validity. This included emotions such as horror and awe which were associated with a new aesthetic category, the sublime. React against reason and the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ with its assumption that all problems can be solved through the application of reason. Romanticism also created and valued childhood as an age of innocence whereas previously children were simply young adults who had not yet grown up. • Value nature. William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge presented poetry as an expression of personal experience filtered through an individual’s emotion and imagination. They believed the truest experience was to be found in nature and the sublime strengthened this through an appeal to the wilder aspects of nature where the sublime could be experienced directly. -

Dutch Painting of the Golden

Dutch painting of the Golden Age About this free course This free course is an adapted extract from the Open University course A226 Exploring art and visual culture: www.open.ac.uk/courses/modules/a226. This version of the content may include video, images and interactive content that may not be optimised for your device. You can experience this free course as it was originally designed on OpenLearn, the home of free learning from The Open University – www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/dutch-painting-the-golden-age/content-section-0 There you’ll also be able to track your progress via your activity record, which you can use to demonstrate your learning. Copyright © 2016 The Open University Intellectual property Unless otherwise stated, this resource is released under the terms of the Creative Commons Licence v4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_GB. Within that The Open University interprets this licence in the following way: www.open.edu/openlearn/about-openlearn/frequently-asked-questions-on-openlearn. Copyright and rights falling outside the terms of the Creative Commons Licence are retained or controlled by The Open University. Please read the full text before using any of the content. We believe the primary barrier to accessing high-quality educational experiences is cost, which is why we aim to publish as much free content as possible under an open licence. If it proves difficult to release content under our preferred Creative Commons licence (e.g. because we can’t afford or gain the clearances or find suitable alternatives), we will still release the materials for free under a personal end- user licence. -

French Classicism in Four Painters: Where It Went and Why

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2019 French Classicism in Four Painters: Where It Went and Why Kristen Tayler Westerduin Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019 Part of the Ancient Philosophy Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Philosophy Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Westerduin, Kristen Tayler, "French Classicism in Four Painters: Where It Went and Why" (2019). Senior Projects Spring 2019. 130. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019/130 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. French Classicism in Four Painters: Where It Went and Why Senior Project Submitted to The Divisions of Art History and Visual Culture and French Studies of Bard College by Kristen T. Westerduin Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2019 Westerduin, 2 Acknowledgements A big thank you to Laurie Dahlberg for taking the time to guide me through this process and answering every question I had, big and small. -

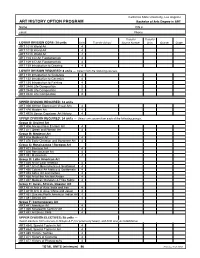

ART HISTORY OPTION PROGRAM Bachelor of Arts Degree in ART Name CIN # Email Phone

California State University, Los Angeles ART HISTORY OPTION PROGRAM Bachelor of Arts Degree in ART Name CIN # email Phone Transfer Transfer LOWER DIVISION CORE: 24 units Units Transfer School Course Number Units Quarter Grade ART 101A World Art 4 ART 101B World Art 4 ART 101C World Art 4 ART 103 2-D Art Fundamentals 4 ART 109 3-D Art Fundamentals 4 ART 159 Introduction to Drawing 4 LOWER DIVISION REQUIRED: 8 units — Select from the following courses. ART 150 Introduction to Sculpture 4 ART 152 Introduction to Ceramics 4 ART 155 Introduction to Painting 4 ART 244A Life Composition 2 ART 244B Life Composition 2 ART 244C Life Composition 2 UPPER DIVISION REQUIRED: 12 units ART 356 Written Expression Visual Arts 4 ART 426 Modern Art 4 ART 492A Senior Capstone: Art History 4 UPPER DIVISION REQUIRED: 24 units — Select one course from each of the following groups. Group A: Ancient Art ART 406 Ancient Near Eastern Art 4 ART 411 Greek and Roman Art 4 Group B: Medieval Art ART 416 Medieval Art 4 ART 476 Early Christian and Byzantine Art 4 Group C: Renaissance / Baroque Art ART 421 Baroque Art 4 ART 436 Renaissance Art 4 ART 451 Mannerism 4 Group D: Latin American Art ART 446 Art of Latin America 4 ART 447 Art of Mesoamerica & Southwest 4 ART 450 Colonial Art Mexico & Guatemala 4 ART 453 Aztec Art and Culture 4 ART 456 Art of the Ancient Andes 4 ART 457 Mexican Muralists & Frida Kahlo 4 Group E: Asian, African, Oceanic Art ART 431A Arts of Asia: India and Iran 4 ART 431B Arts of Asia: China and Japan 4 ART 461 Oceanic/North American Indian Art 4 ART 481 African Art 4 Group F: Contemporary Art ART 441 American Art 4 ART 466 Nineteenth Century Art 4 ART 491 Art Since 1945 4 UPPER DIVISION ELECTIVES: 28 units — Select electives from courses in Groups A-F (not previously taken), and from courses listed below.