Torts: Liability of Owners and Occupiers of Land Mark A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol

Recreational Access to Agricultural Land: Insurance Issues Martha L. Noble* I. Introduction In the United States, a growing urban and suburban population is seeking rural recreational opportunities.^ At the same time, many families involved in traditional agriculture want to diversify and increase the sources of income from their land.^ Both the federal and state govern- ments actively encourage agriculturists to enter land in conservation programs and to increase wildlife habitats on their land.^ In addition, * Staff Attorney, National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information (NCALRI); Assistant Research Professor, School of Law, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. This material is based upon work supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Library under Agreement No. 59-32 U4-8- 13. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this pubUcation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA or the NCALRI. 1. See generally Langner, Demand for Outdoor Recreation in the United States: Implications for Private Landowners in the Eastern U.S., in Proceedings from the Conference on: Income Opportuntties for the Prt/ate Landowner Through Man- agement OF Natural Resources and Recreational Access 186 (1990) [hereinafter Pro- ceedings] . 2. A survey of New York State Cooperative Extension county agents and regional specialists indicated that an estimated 700 farm famiUes in the state had actually attempted to develop alternative rural enterprises. An estimated 1,700 farm families were considering starting alternative enterprises or diversifying their farms. Many alternatives involved recreational access to the land, including the addition of pick-your-own fruit and vegetable operations, petting zoos, bed and breakfast facilities, and the provision of campgrounds, ski trails, farm tours, and hay rides on farm property. -

The Morality of Strict Liability

THE MORALITY OF STRICT TORT LIABILITY JULES L. COLEMAN* Accidents occur; personal property is damaged and sometimes is lost altogether. Accident victims are likely to suffer anything from mere bruises and headaches to temporary or permanent disability to death. The personal and social costs of accidents are staggering. Yet the question of who should bear these costs has turned the heads of few philosophers and has occasioned surprisingly little philo- sophic discussion. Perhaps that is because the answer has seemed so obvious; accident costs, at least the nontrivial ones, ought to be borne by those at fault in causing them.' The requirement of fault at one time appeared to be so deeply rooted in the concept of per- sonal responsibility that in the famous Ives2 case, Judge Werner was moved to argue that liability without fault was not only immoral, but also an unconstitutional violation of due process of law. Al- * Ph.D., The Rockefeller University; M.S.L., Yale Law School. Associate Professor of Philosophy, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The author wishes to acknowledge the enormous impact that Joel Feinberg and Guido Calabresi have had on the philosophic and legal ideas set forth in this Article, and to express appreciation to Mitchell Polinsky, Bruce Ackerman, and Robert Prichard for their valuable assistance. This Article constitutes part of the author's forthcoming book, RESPONSIBIITY AND Loss ALLOCATION OF THE LAW OF TORTS (Ed.). 1. The term "fault" takes on different shades of meaning, depending upon the legal context in which it is used. For example, the liability of an intentional or reckless tortfeasor is determined differently from that of a negligent tortfeasor. -

Can Bystanders Make Failure-To-Warn Claims in Toxic Tort Cases? by Stephen D

THE OLDEST LAW JOURNAL IN THE UNITED STATES 1843-2019 PHILADELPHIA, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2019 VOL 259 • NO. 38 ENVIRONMENTAL LAW Can Bystanders Make Failure-to-Warn Claims in Toxic Tort Cases? BY STEPHEN D. DALY STEPHEN D. DALY is an Special to the Legal attorney with the environ- Despite the mental, energy and land failure-to-warn claim is a use law and litigation firm similarities in staple of products liability of Manko, Gold, Katcher the strict liability and A litigation. The basic premise & Fox, located just outside is that a manufacturer or seller of Philadelphia. He can be negligent failure-to-warn failed to warn a consumer about an reached at 484-430-2338 unreasonable risk of foreseeable harm or [email protected]. theories, the court associated with the use of a product. Plaintiffs pursuing toxic tort cases liability or negligence theories, although dismissed the strict have begun to rely on failure-to-warn the distinction between the two theories liability claim but claims outside the strict consumer/ is murky. The Pennsylvania Supreme seller context. Specifically, several Court, in the context of addressing not the negligence personal injury lawsuits relating to product design defects, has instructed the emerging contaminant per- and that the theory of strict products liability claim. polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) “overlaps in effect” with the theory of have relied on failure-to-warn theories negligence, although the court has tried against manufacturers of PFAS. These to maintain a distinction between the defendant owed a duty to provide lawsuits are distinct from many failure- two theories, as in Tincher v. -

Volk V. Demeerleer Study

Volk v. DeMeerleer Study Commissioned by: Washington State Legislature House Judiciary Committee December 1, 2017 UW School of Law Center for Law, Science and Global Health Volk v. DeMeerleer Study Research Team Tanya E. Karwaki, JD, LLM, PhD Research Associate, Center for Law, Science and Global Health Jaclyn Greenberg, JD, LLM (candidate) Annemarie Weiss, LLM Gavin Keene, JD (candidate) Faculty Supervisors Patricia C. Kuszler, MD, JD Charles I. Stone Professor of Law Faculty Director, Center for Law, Science, and Global Health Terry J. Price, MSW, JD Executive Director, Center for Law, Science, and Global Health VOLK V. DEMEERLEER STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. Comprehensive Review of the “Duty to Warn” and the “Duty to Protect” ............................................ 5 A. Background: The Tarasoff Case and the Duties to Endangered Third Parties ............................... 5 B. Review of Case Law and Legislative Provisions Across the United States ..................................... 7 1. Terminology with Respect to the “Duty to Protect” and the “Duty to Warn” ......................... 7 2. Summary of the National 50-State (plus District of Columbia) Legislative and Case Survey .. 8 a) Description of the Duty to Third Parties ............................................................................. 8 b) Who Has a Duty to Third Parties in the Context of Mental Health Care ......................... -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

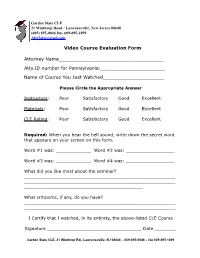

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

Damien A. Macias V. Summit Management, No

Damien A. Macias v. Summit Management, No. 1130, Sept. Term, 2018 Opinion by Leahy, J. Motion for Summary Judgment > Scope of Review Maryland premises-liability law allows disposition on summary judgment when the pertinent historical facts are not in dispute. See Hansberger v. Smith, 229 Md. App. 1, 13, 21-24 (2016); see also Richardson v. Nwadiuko, 184 Md. App. 481, 483-84 (2009). Negligence > Premises Liability >Foreseeability Foreseeability—the principal consideration in actionable negligence—is not confined to the proximate cause analysis. See Kennedy Krieger Institute, Inc. v. Partlow, 460 Md. 607, 633-34 (2018); Valentine v. On Target, Inc., 112 Md. App. 679, 683-84 (1996), aff'd, 353 Md. 544 (1999). Negligence > Premises Liability >Duty The status of an entrant, and the legal duty owed thereto, are questions of law informed by the historical facts of the case. See Troxel v. Iguana Cantina, LLC, 201 Md. App. 476, 495 (2011). Negligence > Duty to Invitees > Condominium Associations Condominium unit owners and their guests occupy the legal status of invitee when they are in the common areas of the complex over which the condominium association maintains control. Barring any agreements or waivers to the contrary, the condominium association is bound to exercise “reasonable and ordinary care” to keep the premises safe for the invitee and to “protect the invitee from injury caused by an unreasonable risk which the invitee, by exercising ordinary care for his [or her] own safety, will not discover.” See Bramble v. Thompson, 264 Md. 518, 521 (1972). Negligence > Premises Liability >Legal Status An entrant’s legal status is not static and may change through the passage of time or through a change in location. -

State of Delaware Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF DELAWARE RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Updated in 2017 by Cooch and Taylor 1000 N. West St., 10th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Phone: (302) 984-3800 www.coochtaylor.com 2017 USLAW Retail Compendium of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS The Delaware State Court System ............................................................................... 2-3 Trial Courts ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 The Justice of the Peace Court .................................................................................................................. 2 The Court of Common Pleas ..................................................................................................................... 2 The Superior Court .................................................................................................................................... 2 The Family Court ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The Chancery Court ................................................................................................................................... 3 Appellate Court ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Supreme Court of the State of Delaware ........................................................................................... 3 General -

Duty to Warn of Naturally Occurring Hazards at Recreational Facilities

www.rbs2.com/ltgwarn2.pdf 30 Sep 2007 Page 1 of 59 Legal Duty in the USA to Warn of Naturally Occurring Hazards At Recreational Facilities Copyright 2007 by Ronald B. Standler Keywords act of God, Breaux, cases, control, danger, dangerous, duty, flood, golf, golfers, hazard, hazardous, hazards, invitee, invitees, law, legal, liable, liability, lightning, MacLeod, Maussner, natural, naturally occurring, ocean, Pacheco, protect, protection, recreational, reliance, relied, rely, ripcurrent, riptide, safety, Sall, shelter, surf, thunderstorm, undertow, warn, warning, water, weather, wind Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Old Legal Rule . 3 invitees, licensees, trespassers . 5 a few cases . 5 reliance . 6 State Statutes . 7 California . 7 Louisiana . 7 New York . 8 Ohio . 10 Pennsylvania . 10 Texas . 11 Act of God . 12 Case Law: Lightning at Recreational Facilities . 14 Davis (golf) . 14 Bier (picnic shelter) . 15 Schieler (National Park) . 16 Hames (golf) . 16 Pichardo (baseball) . 17 McAuliffe (swimming at lake) . 18 Dykema (outdoor basketball game) . 19 MacLeod (mountain peak at National Park) . 20 Maussner (golf) . 22 Blanchard (picnic in park) . 23 www.rbs2.com/ltgwarn2.pdf 30 Sep 2007 Page 2 of 59 Grace (golf) . 24 Jaffe (golf) . 24 Chapple (state park) . 25 Seelbinder (beach) . 25 Patton (after rugby game) . 26 Sall (golf) . 29 reliance in Sall . 30 Mack (softball game at prison) . 32 conclusion . 32 Case Law: Other Natural Hazards at Recreational Facilities . 32 Butts (swimming) . 33 Tarshis (swimming at beach) . 34 Gonzales (riptide) . 34 reliance in Gonzales . 36 Missar (skiing) . 38 Mostert (theater has duty to warn of flood) . 39 Fuhrer (possible duty to warn of riptide) . 41 Caldwell v. -

Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt

South Carolina Law Review Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 6 Winter 2005 Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murraywood Swim & (and) Racquet Club and Goode v. St. Stephens United Methodist Church Matthew D. Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, Matthew D. (2005) "Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murraywood Swim & (and) Racquet Club and Goode v. St. Stephens United Methodist Church," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol57/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lincoln: Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murr LANDOWNERS' DUTY TO GUESTS OF INVITEES AND TENANTS: VOGT V. MURRAYWOOD SWIM & RACQUET CLUB AND GOODE V. ST. STEPHENS UNITED METHODIST CHURCH I. SOUTH CAROLINA ENCOUNTERS THE GUEST ISSUE South Carolina follows traditional premises liability law and defines the duty of care owed by the owner or controller of the premises by reference to categories of entrants, such as invitee and licensee.' A current issue in South Carolina courts is the classification of, and the duty of care owed to, guests of invitees or tenants vis-i-vis the landowner. The issue has presented itself in two scenarios: first, when the guest of a private club member is injured on the club's premises; and second, when the guest of a tenant is injured in the common area of the leased premises. -

Premises Liability - Defense Perspective

PREMISES LIABILITY - DEFENSE PERSPECTIVE Carol Ann Murphy HARRISBURG OFFICE CENTRAL PA OFFICE 3510 Trindle Road MARGOLIS P.O. Box 628 Camp Hill, PA 17011 Hollidaysburg, PA 16648 717-975-8114 EDELSTEIN 814-695-5064 Carol Ann Murphy, Esquire PITTSBURGH OFFICE The Curtis Center, Suite 400E SOUTH JERSEY OFFICE 525 William Penn Place 100 Century Parkway Suite 3300 170 South independence Mall West Suite 200 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Philadelphia, PA 19106-3337 Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 412-281-4256 215-931-5881 856-727-6000 FAX (215) 922-1772 WESTERN PA OFFICE: NORTH JERSEY OFFICE [email protected] 983 Third Street Connell Corporate Center Beaver, PA 15009 400 Connell Drive 724-774-6000 Suite 5400 Berkeley Heights, NJ 07922 SCRANTON OFFICE 908-790-1401 220 Penn Avenue Suite 305 DELAWARE OFFICE: Scranton, PA 18503 750 Shipyard Drive 570-342-4231 Suite 102 Wilmington, DE 19806 302-888-1112 www.margolisedelstein.com PREMISES LIABILITY - DEFENSE PERSPECTIVE In evaluating a case from a defense perspective one must review several issues in determining whether the potential for liability exists. I. STATUS OF CLAIMANT In reviewing a premises liability case, one must determine the status of the claimant. That is, under Pennsylvania law, the determination of the duty of possessor of land toward a third party entering the land depends on whether the entrant is a trespasser, licensee or invitee. Updyke v. BP Oil Company, 717 A.2d 546, 548 (Pa. Super. 1998). A. Trespassers The Restatement (Second) of Torts defined a trespasser as "a person who enters or remains upon land in the possession of another without the privilege to do so created by the possessor's consent or otherwise." Restatement (Second) of Torts § 329. -

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sp

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sperling, Roehl, Harris & Sisk, P.A. Post Office Box 2168 Bank of America Centre 500 Fourth Street NW, Suite 1000 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103-2168 Telephone: 505.848.1800 Email: [email protected] Every employer is concerned about potential liability for the tortious actions of its employees. Simply stated: Where does an employer’s responsibility for its employee’s actions end, the employee’s personal responsibility begin, and to what extent does accountability overlap? This article is intended to detail the various derivative negligence claims recognized in New Mexico that may impute liability to an employer for its employee’s actions, the elements of each claim, and possible defenses. This subject matter is of particular importance to New Mexico employers generally and transportation employers specifically. A. Elements of Proof for the Derivative Negligent Claim of Negligent Entrustment, Hiring/Retention and Supervision In New Mexico, there are four distinct theories by which an employer might be held to have derivative or dependent liability for the conduct of an employee.1 The definition of derivative or dependent liability is that the employer can be held liable for the fault of the employee in causing to a third party. 1. Respondeat Superior a. What are the elements necessary to establish liability under a theory of Respondeat Superior? An employer is responsible for injury to a third party when its employee commits negligence while acting within the course and scope of his or employment. See McCauley v. -

Duty to Protect Or Warn What Those Situations Are (Striefel, 2003, 2004)

Biofeedback ©Association for Applied Psychophysiology & Biofeedback Volume 36, Issue 3, pp. 86–89 www.aapb.org PROFESSIONAL ISSUES Duty to Protect or Warn Sebastian “Seb” Striefel, PhD Department of Psychology, Utah State University, Logan, UT Keywords: duty, warn, protect, risk assessment, confidentiality Violence is a fact of life. As such, virtually every state has Health care professionals—by virtue of being pro- laws specifying that health care professionals have a duty fessionals—are holding themselves out to the public as to protect or warn, and the specific legal requirements having special knowledge and skills in the form of services vary from state to state and discipline to discipline. Every for which some clients and some third parties are willing biofeedback practitioner providing mental health care to pay. Being a professional means that one has special and related services should be familiar with the relevant obligations and responsibilities to those served and often laws of the state in which he or she practices and with to others as specified in ethical principles (Association for the court precedents related to that law. Being able to Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 2003), practice deal appropriately with the relevant issues surrounding guidelines and standards (Striefel, 2004), and laws. This confidentiality and the ability to assess for, predict article will focus primarily on health care professionals’ dangerousness to self and others, and deal with the same are responsibilities as specified in the duty to protect and/or expected standards of care that can vary in implementation warn laws. from state to state. Consultation with colleagues and/or an attorney can be important.